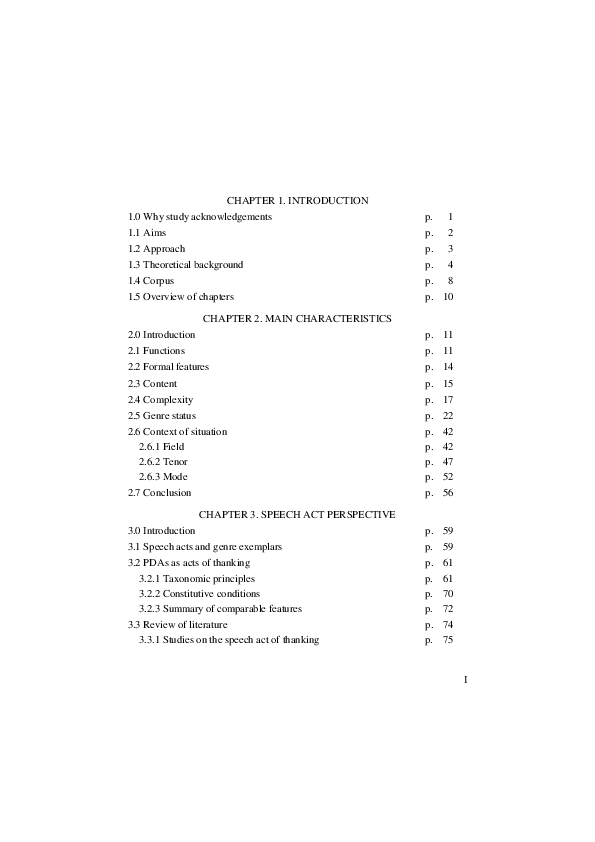

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

1.0 Why study acknowledgements

p.

1

1.1 Aims

p.

2

1.2 Approach

p.

3

1.3 Theoretical background

p.

4

1.4 Corpus

p.

8

1.5 Overview of chapters

p. 10

CHAPTER 2. MAIN CHARACTERISTICS

2.0 Introduction

p. 11

2.1 Functions

p. 11

2.2 Formal features

p. 14

2.3 Content

p. 15

2.4 Complexity

p. 17

2.5 Genre status

p. 22

2.6 Context of situation

2.6.1 Field

2.6.2 Tenor

2.6.3 Mode

p.

p.

p.

p.

2.7 Conclusion

p. 56

42

42

47

52

CHAPTER 3. SPEECH ACT PERSPECTIVE

3.0 Introduction

p. 59

3.1 Speech acts and genre exemplars

p. 59

3.2 PDAs as acts of thanking

3.2.1 Taxonomic principles

3.2.2 Constitutive conditions

3.2.3 Summary of comparable features

p.

p.

p.

p.

3.3 Review of literature

3.3.1 Studies on the speech act of thanking

p. 74

p. 75

61

61

70

72

I

�3.3.1.1 Impact of contextual variables

3.3.1.2 Encoding of gratitude: form and function

3.3.2 Studies on ASs

3.3.2.1 The professional-social value of ASs

3.3.2.2 Realization patterns of the main notions

3.4 Implications of findings

p.

p.

p.

p.

p.

75

83

89

89

96

p. 104

CHAPTER 4. ANALYSIS OF TEXTS

4.0 Introduction

p. 107

4.1 Basis for the analysis

4.1.1 Sample analyses

p. 107

p. 108

4.2 Identification of AMs

4.2.1 Identifiability of a hierarchical structure within AMs

p. 114

p. 120

4.3 Size

p. 123

4.4 Titles

p. 127

4.5 Global structure

4.5.1 Introductory and concluding moves

4.5.1.1 Micro introductory and concluding moves

4.5.2 Order of benefactors

4.5.3 Syntax (and semantics) of AMs

4.5.4 Conclusion

p.

p.

p.

p.

p.

p.

4.6 Benefactor units

4.6.1 Benefactor expansions

4.6.2 Conclusion

p. 146

p. 159

p. 165

4.7 Benefit units

4.7.1 Benefit expansions

4.7.2 Conclusion

p. 166

p. 176

p. 181

4.8 Gratitude expressions

4.8.1 Expansions of gratitude expressions

4.8.2 Conclusion

p. 182

p. 194

p. 199

4.9 An approach to the grammar of thanking

p. 200

II

128

128

132

134

139

145

�4.9.1 Patterns in gratitude expressions and expansions

4.9.2 Patterns in benefactor units and expansions

4.9.3 Patterns in benefit units and expansions

4.9.4 Global patterns

4.9.4.1 AMs with no gratitude expressions

4.9.4.2 AMs with gratitude expressions

4.9.4.3 Multi-clause AMs

4.9.5 Summary of patterns

4.10 Concluding remarks

p.

p.

p.

p.

p.

p.

p.

p.

203

207

213

218

218

221

225

228

p. 229

CHAPTER 5. CONCLUSIONS

5.0 Introduction

p. 235

5.1 The nature and value of PDAs

p. 235

5.2 Contribution of the analysis and summary of features

p. 241

5.3 Future perspectives

p. 244

REFERENCES

p. 247

III

�CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.0 WHY STUDY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Among academic genres, acknowledgements enjoy a privileged status. From

a typographic viewpoint, they occupy a distinct, dedicated textual space, which

makes them easily identifiable. From a functional viewpoint, they are

characterized by a focused topic and goal, which makes them easily

interpretable. Most importantly, from an interactional viewpoint, they bridge the

gap between two facets of the writer’s lifeworlds – the public prominence of

their scholarly figure and the intimate domain of their private life, which

qualifies them as a revealing link between the writer, their work and their

readership.

Set as they are at the interface between private and public communication,

acknowledgements provide an instructive and entertaining glimpse into the

context surrounding the coming to life of a textual product. They are instructive

because they inform the reader of the circumstances that have accompanied and

affected the writing process, which are not otherwise reported in the main text

the acknowledgements are relevant to. They are entertaining because their

content and wording are light, and while useful to a better appreciation of the

larger text they preface, they are not indispensable to its full understanding.

These features frame acknowledgements as a relaxing interactional oasis before

a more demanding, intensive and prolonged interpretive textual task.

Acknowledgements in academic texts are particularly interesting because

they hint at the tension underlining the contrasting demands placed on the author

by the latter’s multi-faceted interactional role-relationships. On the one hand,

acknowledgements offer the scholar a relatively unconstrained opportunity to

mention what matters to them: maybe a carefully selected and specially edited

representation of their self – their Goffmanian face, to be projected and put at

stake in the interaction – meant to portray them as likeable and reliable. In this

respect, acknowledgements are the conventionally agreed-upon, liberating

textual territory were authors can be themselves, or represent the self they want

to appear to be. On the other hand, acknowledgements present authors with the

chance to balance out the social debts incurred during, and as a result of, the

1

�Acknowledgments: structure and phraseology

writing process – their deeply felt, or conventionalized, and motivated gratitude

– meant to map out their professional allegiance, intellectual affiliation and

cultural dependence on others. In this second respect, acknowledgements are a

constraining, potentially dangerous interactional space, where benefactors’

feelings can get hurt and where authors can undermine their future academic

prospects, if benefactors are not shown “due” deference.

There are therefore several reasons why acknowledgements are worth

studying. They are spontaneously produced communicative acts: they are

planned and revised, but not specially elicited. They exemplify elaborate speech

acts: their rich content, composite structure, and focus on relational needs

reveals the interpersonal significance they are laden with. They are not

formulaic: although conventional in purpose, they are realized through a variety

of lexico-grammatical means which leave room for innovative wording. Also,

despite their specific, almost obvious goal-oriented nature, they are not

straightforward, let alone banal, communicative acts in any way: they present

internal contradictions which affect their global organization and linguistic

encoding; for instance, they are public documents which contain private

information about personal circumstances; they are conceptually separable from,

but physically attached to, the larger texts they introduce; their rationale is the

expression of gratitude, but their focus is on the description of benefits and

benefactors that gratitude is relevant to. Finally, they are virtually ubiquitous in

academic writing: acknowledgements can accompany academic books, journals

articles, book chapters, proceedings papers; their frequency – and, in the case of

books and dissertations, their length too – suggests that their authors consider

them professionally and/or personally valuable.

What, then, makes acknowledgements valuable? Why do people write them?

What is in them for their writers and readers? When are they communicatively

effective and interactionally appropriate? What are their official and underlying

goals? How can one tell if their goals have been achieved? Do they follow a

standard format? Are they predictable in content? What are their recurrent

phraseologies? The present work sets out to describe the thematic topics,

structural components and encoding patterns in acknowledgements as can be

found in PhD dissertations.

1.1 AIMS

This book presents a textual analysis of the discursive strategies employed by

PhD candidates who publicly acknowledge their benefactors in written texts for

help received while writing their dissertations. The broader aim of the study is to

2

�Introduction

provide a description of the content and structural organization of PhD

dissertation acknowledgements (henceforth PDAs) with regard to the relevant

contexts of situation and culture. The more specific objectives include: defining

PDAs as extended speech acts of thanking; identifying their recurrent functional

components; outlining the lexico-grammatical patterns of realization of the main

components of their constituent Acknowledgement Moves (henceforth AMs).

My analysis focuses on increasingly specific aspects of PDAs. I first

examine the genre status of these communicative acts, that is, (the reasons for)

their noticeable textual homogeneity as well as their degree of internal

variability. Next, I explore their most salient global characteristics (in terms of

structure, functions and content). I then motivate a definition of them as macro

speech acts of thanking and outline their basic recursive structure; in other

words, I show how a PDA writer’s main communicative purpose (i.e. an

expressive illocutionary intent) is made relevant to multiple, comparable

interactional settings. I proceed to identify the core and supportive functional

units of PDAs’ component moves, which reveal the importance of the

interpersonal dimension of communication. Finally, I detail their linguistic

encoding; that is, I illustrate their lexico-syntactic ways of expressing gratitude,

whether conventional and typified or innovative and original.

This work is thus meant to contribute to an identification of generic

properties as relatable to the situational and cultural contexts in which PDAs are

produced, to an understanding of what extended speech acts (of thanking)

consist of, and to a description of the lexico-grammar of thanking in writing.

1.2 APPROACH

The study combines a qualitative description of the PDA genre, in general,

with a quantitative examination of a set of PDAs, in particular. The description

includes a definition and characterization of PDAs from a formal and functional

point of view. That is, I examine in detail their illocutionary nature (i.e. the

expression of a specific reactive psychological state), account for their main

properties in relation to their communicative rationale, discuss their

communicative complexity and relevance to the interactants’ interpersonal

needs, and point out the features worth exploring in PDAs on the basis of

findings from studies of comparable kinds of texts. In sum, by outlining their

typical context of situation and by drawing on insights from speech act theory

and genre studies, I provide a pragmatic account of the interactional role and

value of PDAs. To this end, I also include sample detailed descriptions of PDAs

3

�Acknowledgments: structure and phraseology

excerpts meant to reveal how the patterns relevant to the encoding gratitude are

actually instantiated in complete texts (see chapters 2, 3 and 4).

The complementary, quantitative analysis involves a series of steps: the

determination of a text sampling procedure (i.e. the decision of which PDAs to

collect: how many, from where, and why); the collection and electronic

formatting of the sampled texts; the elaboration of a coding scheme for the

analysis of formal and functional properties of the texts; the identification,

classification and manual tagging of the PDAs’ moves, move components and

their lexico-grammatical encoding options; the identification, classification and

manual tagging of the main notions conveyed and of their sequencing patterns in

the texts; and the importing of the raw and tagged data into worksheets for the

analysis of the frequency and distribution patterns of the above features. The

aim of the quantitative analysis is to provide an account of what is typical of the

genre (e.g. frequency, distribution, order and encoding of moves and notions)

and of its degree of internal variation on the basis of actual textual data (see

chapter 4).

The combined quantitative-qualitative approach adopted is aimed at

describing and accounting for the elaborate linguistic make-up of PDAs,

identifying the socially relevant communicative actions performed through

them, and assessing their social salience in the cultural context in which they are

produced (see chapter 5).

1.3 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

The research presented here is relevant to the disciplines of pragmatics, text

linguistics, genre studies, and corpus analysis.

Pragmatics aims at describing and accounting for co- and con-textualized

language use, in particular the relationship between language form and language

function (i.e. the addresser’s strategic use of language for the achievement of

linguistic and non-linguistic ends), and the relevance of cognitive and sociocultural expectations to the interpretation assigned to and the effects determined

by units of speech or writing in specific settings (i.e. the addressee’s

participation in the co-construction of meaning).

My analysis aims at describing how dissertation writers construct, maintain

and shape their relationships with their benefactors, and their readers, by

performing exchanges of services through the use of language; it is also meant

to account for the typical elaborateness of these texts by referring to the shared

and unshared backgrounds of the participants involved in the communicative

act; furthermore, it specifically describes PDAs as speech acts of thanking. More

4

�Introduction

generally, it offers a possible, context-based explanation for PDA authors’

attempts to achieve both communicative effectiveness (as writers of semiofficial documents meant for a public audience) and interpersonal acceptability

(as individuals aware of their social obligations and interactional

responsibilities). For these reasons, this study lies in the domain of pragmatics.

A theoretical approach directly relevant to the intended analysis is offered by

the pragmatics of speech act theory as developed by Austin and Searle.

According to speech act theory, the basic unit of communication is the speech

act, an intentional act that a speaker realizes with words in order to achieve a

given purpose in relation to the hearer (Searle 1969: 21). Every speech act can

be labelled with a name identifying its communicative essence, is governed by

rules (i.e. requires the fulfilment of co- and con-textual conditions), enacts one

of a few main types of communicative exchanges, may realize multiple

functions, and may be encoded through a number of linguistic means.

Similarly, PDAs can be defined in terms of what their authors want to carry

out through them in relation to their addressees (i.e. express feelings that help

restore the balance of social credits and debts); they can make sense and be

effective if certain pre-conditions are met (e.g. their writers must have

completed their dissertations and are supposed to feel indebted to their helpers

and supporters); they fulfil complementary purposes through their functional

components (which may serve to compliment benefactors, explain to the reader

the authors’ relationship to the benefactors, and describe benefits received) and

also through their reliance on contextual information (i.e. the intention to thank

may be implied and recovered from the accompanying units of information).

Particularly useful for the study of elaborate communicative acts

interpretable as instantiations of speech acts is the contribution of Cohen and

Olshtain (1981) and Blum-Kulka, House and Kasper (1989) to the analysis of

extended speech acts and speech act sets. Their approach consists in paying

attention to the specific and variable lexico-grammatical encoding of the gist of

the speech act (i.e. the possible strategies for manifesting the relevant illocution)

and in examining its immediate co-text (i.e. identifying the type, determining the

sequence and classifying the variable realization of its possible complementary

functional units and/or corollary speech acts). As carefully planned, originalityoriented, composite texts that contain several units of information and may carry

out multiple functions, PDAs lend themselves to an analysis that considers both

the variety of linguistic means available for their encoding and the variable

organization of their structural components, which can be adapted to everchanging contextual needs.

5

�Acknowledgments: structure and phraseology

Text linguistics deals with the classification and description of stretches of

speech or writing that function as cohesive, coherent and self-contained units of

communication. One of my goals is indeed to describe the formal and functional

structure of complete and organic units of language use by relating them, on the

one hand, to the interactants’ communicative purposes and strategies, and on the

other hand, to the options offered and the constraints imposed by the situational

context. The analysis I present considers both macro (i.e. structural, contentrelated) and micro (i.e. stylistic, lexico-syntactic) characteristics of PDAs in an

attempt to account for their interpretability (i.e. understandability, unity,

completeness, orientation towards a specific goal, and mutual relevance of their

component parts). As a result, this study counts as an exercise in text linguistics.

An inspiring theoretical approach to a textual examination of PDAs is

provided by systemic functional linguistics (e.g. Downing and Locke 2002,

Eggins 1994, Halliday 1994, Martin 1992). Its assumptions are that language

users’ choices depend, on the one hand, on the options offered and constraints

imposed by the linguistic system available to them (e.g. in terms of phonology,

lexicon, syntax), and on the other hand, on the contexts of situation and culture

in which they produce their texts. Systemic functional linguistics proposes an

analysis of the threefold structure of the clauses that make up a stretch of speech

or writing (i.e. as representations that encode experience, as exchanges that

convey interpersonal meanings, and as messages that build stretches of text) that

shows how the lexico-grammatical make-up of a given text (in particular its

transitivity, modality and thematic structures) is systematically linked to the kind

of interactional event it is part of, the role-relationships between the interactants,

and the cohesive and strategic organization of the communicative act itself

(technically called the field, tenor and mode of the context of situation,

respectively). In short, systemic functional linguistics offers viable guidelines

for accounting for the linguistic characteristics of a text by correlating them to

relevant properties of the context of situation.

Characterizing given texts’ contexts of situation and describing their

multifunctional encoding of meanings about reality, relations, and language

behaviour (see Halliday 1978) is particularly useful in the case of PDAs. Their

writers set the encoding of such meanings as their overt aims: they purposely

record professional and personal experiences that constitute the background of

their dissertation projects; they enact interactional roles meant to manage at least

temporarily unbalanced social relationships; they present carefully planned

linguistic products that create expectations about their reception and function in

the interaction. As a result, the concepts and descriptive criteria of systemic

functional linguistics are particularly relevant to a description of the

6

�Introduction

interrelationships between their wording, their meanings, and their culturalcontextual relevance of PDAs.

Genre studies identify, classify and describe the shared semantic and stylistic

properties of communicative acts that can be grouped together due to a common

(set of) main purpose(s). My examination of PDAs is in line with these research

objectives in three respects: first, it involves determining what linguistic,

structural and functional features PDAs share such that they can be considered

instantiations of the same kind of communicative act; also, it aims at revealing

their degree of internal variation; and finally it is meant to identify their

prototypical realization. Precisely because it draws attention to what makes a

PDA a PDA (i.e. its communicative purpose and the properties instrumental to

it), this work also makes a contribution to genre studies.

Genre studies of non-fictional texts as carried out by Swales (1990) and

Bhatia (1993) have convincingly described genres as sets of partially or totally

linguistic, purpose-oriented, conventionalized communicative acts which

provide the members of given discourse communities with the means to

successfully engage in recurrent interactional practices. PDAs constitute such a

class since they are meant to satisfy a purpose (i.e. expressing a favourable

attitude towards the writers’ benefactors) by means of conventional procedures

(i.e. describing the benefits received and identifying the relevant benefactors)

and through the medium of language (i.e. both stylistically and content-wise,

PDAs represent finished linguistic products). The criteria adopted by the above

scholars for defining and describing such genres are therefore also applicable to

PDAs as goal-oriented conventionalized communicative acts.

Corpus analysis of Languages for Specific Purposes (henceforth LSPs)

consists in the computer-assisted identification and description of the most

frequent and typical patterns of realization of meanings in large samples of texts

produced in relation to given specialized activities. My analysis of PDAs

includes listing, classifying and quantifying their various lexico-grammatical

forms of encoding gratitude and its supportive notions as well as detecting their

structural organization by automatically retrieving words, collocations, and

appropriately tagged text segments. Because it systematically examines various

types of features of a body of texts in electronic format, assembled for linguistic

description and representative of the same type of communicative act, this study

can also be said to apply the methods of corpus linguistics to text analysis.

Corpus linguistic studies have repeatedly shown (e.g. Kennedy 1998) that

several aspects of LSPs (e.g. connotations of individual words, typical

7

�Acknowledgments: structure and phraseology

collocations, text-specific syntactic structures) can be revealed by examining

numerous examples of similar authentic texts produced within a given discourse

community. For example, frequency lists of running words, concordances

showing the co-text of given wordforms or expressions, the ratio between word

types and tokens, part-of-speech tagging and lemmatization of texts are among

the instruments that reveal in what ways and to what extent LSP texts are similar

to or differ from Language for General Purposes texts. The texts I consider are

in electronic format, manually tagged for various linguistic and textual features,

and thus amenable to corpus processing analysis. The automatic retrieval of

individual words or text segments and counting of their frequency of occurrence

and patterns of co-occurrence provides quantitative evidence of actual language

use and reveals the degree of homogeneity or variation among the texts

examined.

This study draws on the insights and resources of complementary linguistic

sub-disciplines. By combining different lines of research into a unified analysis,

I provide a co(n)textualized examination of PDAs so as to categorize their

content and the forms of its realization, to provide a motivated interpretation of

them as macro acts of thanking, and to describe their shared structural, semantic

and formal properties in relation to their contexts of production and reception.

1.4 CORPUS

The corpus analysed comprises 50 PDAs written by PhD candidates at the

University of California (henceforth UC) at Berkeley in the 1990’s. The texts

were collected partly manually at the UC Berkeley libraries and partly

electronically on the Internet, together with their title pages.1 The paper texts

were scanned and proofread, and then all the texts were imported into Text files

so as to have the corpus in electronic format, ready for manual and computerassisted analysis. I grouped the texts into ten sets (i.e. one per academic

discipline), and within each, I ordered the texts alphabetically by the authors’

last names.2

The PDAs represent ten of the disciplines that UC Berkeley offers doctoral

programs in. These are English (henceforth Engl) and Philosophy (henceforth

1

This ensured that I could easily recognize the names of the PhD candidates’ dissertation

committee members in case these professors were mentioned in the PDAs without reference

to their academic titles and/or roles.

2

Two last names occurred twice, and in such cases I considered also the authors’ first names

to order the texts alphabetically.

8

�Introduction

Phil) for the Humanities; Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

(henceforth EECS), Physics (henceforth Phys) and Plant and Microbial Biology

(henceforth P-Bio) for the Applied and Pure Sciences; Economics (henceforth

Econ), Education (henceforth Edu) and Statistics (henceforth Stat) for the Social

Sciences; and Architecture (henceforth Arch) and Business Administration

(henceforth B-Adm) for the Professionally Oriented Disciplines.

The corpus therefore comprises ten sub-corpora, each including five PDAs.

As a whole, the corpus consists of 14,459 words,3 and more specifically: 2,052

in Arch, 835 in B-Adm, 1,080 in Econ, 2,054 in Edu, 1,847 in EECS, 2,369 in

Engl, 814 in Phil, 935 in Phys, 1,607 in P-Bio and 866 in Stat. The corpus size is

thus in keeping with current standards for the compilation of LSP corpora

(Bowker and Pearson 2002).

The texts examined display both similarities and differences. First of all, they

exemplify the same specialized language (academic English as produced by

budding experts) in a context where English is the native and official language;

also, they instantiate the same genre given that they are motivated by the same

communicative rationale (expressing gratitude for help obtained when carrying

out one’s dissertation project); they also share elements of the context of

situation: they were written within one institution, over the same period of time,

in the same language, and by people belonging to the same professional group.

On the other hand, those texts were written within ten different discourse subcommunities (as identifiable by the academic disciplines they are relevant to) by

authors of both sexes (as can be understood from their names), and differ in

length, detail and tone4.

As a result of the above similarities and differences, the corpus appears to be

quite, but not completely, homogeneous: some of the situational, independent

variables (e.g. text type instantiated and main subjects dealt with) are constant,

which ensures that the texts are comparable; but in addition, it presents a little

internal variation (mainly with regard to its inter-disciplinary sources), which is

meant to reduce the possible over- or under-occurrence of certain characteristics

possibly typical of only a subset of the genre considered. Therefore, the sample

of texts considered can be regarded as a fairly balanced set of PDAs, suitable for

3

The automatic word count used is not, however, totally reliable since it treats uninterrupted

strings of all graphic symbols including apostrophes (e.g. father’s, didn’t, 1990’s) as single

orthographic words.

4

A reason for this may also be that the Graduate Division does not provide any official

guidelines to follow for the writing up of PDAs (cf. Swales and Feak 2000: 198).

9

�Acknowledgments: structure and phraseology

an analysis of the PDA genre. However, given the small size of its sub-corpora,

it is not amenable to statistically oriented cross-disciplinary comparisons.

1.5 OVERVIEW OF CHAPTERS

This dissertation presents a textual analysis of 50 US PDAs. More

specifically, it defines those texts as macro speech acts of thanking and

examines the patterns of realization of their component functional units.

Chapter 1 is the introduction: it outlines the objectives of the research and

identifies its relevant theoretical background; in addition, it points out the

contribution that the study offers to linguistics, describes the corpus to be

analyzed, and presents a synopsis of the following chapters.

Chapter 2 defines PDAs from both a functional and a formal point of view,

specifies what recurrent themes make up their subject matter, explains the

reasons for their communicative complexity, indicates what properties qualify

them as a genre, and characterizes their typical context of situation.

Chapter 3 focuses on the speech act nature of PDAs. It discusses the

comparability between (complex) speech acts and genre exemplars; it offers a

motivated description of the PDA as an elaborate act of thanking; it reviews

relevant literature on the speech act of thanking and acknowledgment sections

(henceforth ASs); and it shows what components and features of acts of thanking

in general are also relevant to PDAs in particular.

Chapter 4 examines the corpus from both a macro and a micro perspective. It

explores the global structure and characteristics of the PDAs and the specific

wording of single AMs occurring in them. It includes a qualitative analysis of

selected texts and text excerpts, which reveals the variety of lexico-grammatical

patterns available for the encoding of written acknowledgments and also shows

the partly ambiguous nature of specific textual phenomena, which turn out to be

difficult to classify. It also comprises a quantitative summary of the encoding

patterns identified in the corpus (i.e. the strategies for the expression of

acknowledgments and the structural arrangement of the PDAs), whose

occurrence is accounted for with reference to the relevant context of situation. In

addition, it systematically outlines the principles adopted to consistently identify

and classify the structural and notional components of the PDAs.

Chapter 5 derives the conclusion from the findings presented and evaluates

the study as a whole. It summarizes the main features of PDAs and offers an

interpretation as to why these texts are socially valued. Finally, it points out the

value of the contribution made by this study, and offers suggestions for further

research on PDAs.

10

�CHAPTER 2

MAIN CHARACTERISTICS

2.0 INTRODUCTION

PDAs are contextualized units of language use through which dissertation

writers create and sustain social ties by producing meanings. In this chapter I

present a functional and a formal definition of such texts: the former highlights

their interactional properties, which derive from their role as a type of social

exchange; the latter reveals their main global characteristics, which are relatable

to their typical context of situation. I also explain why PDAs are likely to be

elaborate, rather than formulaic, texts. In addition, I motivate a definition of

them as a genre, that is, I indicate why they count as a specific kind of

communicative acts with shared properties. Finally, I provide an overview of the

typical context of situation in which PDAs are used. Illustrative examples from

the corpus are provided throughout.

2.1 FUNCTIONS

From a functional point of view, a PDA is a transactional-communicative act

set in a larger, staged interaction. It is a means through which the dissertation

writer both acknowledges her1 participation in various interactional events and

maintains her interpersonal contact with her interlocutors. Adopting terms and

concepts from systemic-functional linguistics (Tsui 1989), a PDA can be

defined as a delayed, supporting, responding move relevant to several

exchanges, where move is to be intended as an act of participation in the

interaction and exchange as a set of logically ordered interactional acts which

interlocutors take turns uttering.

A PDA is an interactional move, albeit an extended one, because, like a turn

in a conversation, it constitutes one utterance through which the dissertation

writer takes part in a multi-phase speech event with her interlocutors. Organized

1

From now on, when making reference to the dissertation/PDA writer in the singular, I will

employ feminine personal pronouns and possessives. In parallel, when referring to the

dissertation reader in the singular, I will employ masculine third person pronouns and

possessives.

11

�Acknowledgments: structure and phraseology

as a self-contained unit of language use, which develops around one main notion

and is delimited by clear typographic boundaries, the PDA enables its writer to

make one meaningful contribution to an interaction consisting of a series of

moves (see the sample analyses of PDAs in section 4.1.1). These moves include:

(a) the author’s (possibly indirect and possibly recurrent) request for help, (b)

her benefactors’ (possibly repeated) offer or provision of help, and (c) a final

exchange of information between the author and her readers (and possibly her

benefactors) about those requests and offers in the form of a monologic, written

communication act. Thus, PDAs are instances of typified located actions, set in

and constrained by a diachronically ordered network of intertextual, dialogic

communicative acts, which form interrelated systems of genres (Bazerman

1994: 97-98; cf. Räisänen 1999).2

A PDA is also a responding move because it presupposes and reacts to

previous interactional contributions (cf. Coulmas 1981: 71), more specifically

offers of information and/or goods-and-services3, that is, benefits; e.g.:

(1) “[…] has not only been a supportive mentor but a good friend as well. We

have had many personal conversations which I did not imagine possible

with an advisor, and she has given many [sic] invaluable advice on my

personal life” (EECS1;4 reference to offers of information)5

(2) “The project could not have been brought to its present completion without

the support and contribution of many people” (Edu5; reference to offers of

services)

(3) “I would like to thank […] for their valuable suggestions, comments and

time” (B-Adm1; reference to offers of information and services).

A PDA is a delayed response because it is removed in time and place from

the solicitations of interaction it refers to. That is, it is produced after the writer

has benefited from her interlocutors’ offers (see Giannoni 1998: 61) or presented

as such (see Swales and Feak 1994/2004: 204). This is apparent from the use of

past tenses and the occasional reference to non-recent past events; e.g.:

2

On a similar note, Ben-Ari (1987: 68) points out that ASs are perceivable as parts of

ongoing relationships.

3

The speech function of offers is described in Halliday (1994: 69-71).

4

Here and elsewhere, the number following the abbreviated name of the discipline/sub-corpus

identifies the specific text the excerpt is taken from.

5

In this and other examples, emphasis is added, unless otherwise specified.

12

�Main characteristics

(4) “[…] originally suggested to me the idea of working on […]. […]’s acute

criticism saved me from many mistakes. […] gave me the opportunity to

read […]” (Phil1; use of past tenses in relation to benefits)

(5) “I am very grateful to many professors and colleagues for interesting

discussions and for guidance during the last few years” (B-Adm1;

reference to the non-recent past in which benefits were provided)

(6) “I am particularly indebted to the architect […], who spent many long hours

working with me on the […] as I began my research” (Arch3; use of the

past tense and reference to non-recent past events in relation to benefits).

A PDA is also a supporting move because it fulfils the interactional

expectation of the offers of help it responds to: through the PDA, the writer

expresses acceptance of – and thus sustains – the manifestations of support

received from various helpers; e.g.:

(7) “Many individuals provided excellent guidance and inspiration for this

research” (Arch1; reference to the author’s high number of helpers)

(8) “I am deeply grateful to my family and my professors for their unwavering

support of this degree” (Edu2; reference to two categories of benefactors).

Finally, a PDA is relevant to several exchanges because it refers to and

rounds off previous transactions in which the writer was involved as a receiver

of goods, services and/or information: the PDA author manifests acceptance of

the benefits received, confirms the validity and common relevance of those

transactions to specific academic goals, and brings closure to this multi-stage

interaction by verbally re-enacting the role of a beneficiary; e.g.:

(9) “My work has benefited from conversations with colleagues, former

teachers, and new acquaintances” (Phil2; referring to the author’s past role

as a receiver of benefits)

(10) “I was fortunate to work with many many wonderful and knowledgeable

individuals throughout my Ph.D. study. This research and its presentation

today was [sic] only possible because of the quiet dedication and insight of

many friends and colleagues” (P-Bio3; recognizing the validity of benefits

received)

(11) “For many forms of support – emotional, financial, intellectual, and

culinary – I thank the aunts, uncles, parents, grandparents, siblings, and

nephews […]” (Econ1; combined reference to the author’s benefactors and

to the similar nature of their benefits)

13

�Acknowledgments: structure and phraseology

(12) “[…] but it is one of the great pleasures of my life as a writer finally to

record the acknowledgements I have been impatiently saving up all these

years” (Engl3; re-manifesting gratitude for benefits).

2.2 FORMAL FEATURES

From a formal point of view, a PDA is a communicative act distinct from its

surrounding co-text and separate from the context it originated in. In Ehlich’s

(1983, 1984) terms, it is a text, i.e. an independent unit of language use.

For one thing, a PDA is characterized by marked typographic boundaries, a

homogeneous layout, and a focus on one main topic. This stresses the PDA’s

internal coherence and unity (see the sample analyses in section 4.1.1). Its selfcontained nature may be highlighted by the use of cohesive ties; e.g.:

(13) “First, I would like to thank the students who participated in these design

studies. […]. Also, I was fortunate to be in close collaboration with their

teacher […]. Particularly, […] helped me truly comprehend the numerous

hats involved with being an educational researcher. […]. I also wish to

thank the other members of my committee, […]. Additionally, […]

provided valuable feedback in early aspects of this work. Generally, I thank

the […] faculty for creating an interesting place for hybrids to spend some

time. Also, this endeavor would not have been nearly as pleasant nor [sic]

as productive if not for my close collaborator and dear friend […]. And, I

have also appreciated the hours of enjoyment shared with […]. […]. Most

of all, I am indebted to my wife and graduate school partner […]” (Edu3;

cohesive linkers stressing textual coherence).

Secondly, a PDA is easily and conveniently identified as a distinct

communicative act through its label, Acknowledgements. This title – found in all

the PDAs except Engl5 – encapsulates its communicative salience (i.e. its

orientation towards the writer’s helpers’ accomplishments and merits) and thus

signals its conceptual separability from the dissertation it is attached to (whose

focus is on the writer’s abilities and independently achieved results).

In addition, a PDA makes explicit its links with the previous relevant co-text,

whose most salient content is reproduced or summarized through unambiguous

reference to the author’s benefactors and benefits. Such notions would not

otherwise be easily accessible to the reader – who may or may not be one of the

writer’s benefactors – given that the PDA is relevant to various interactions

developed in a number of contexts (see section 2.4; cf. Hyland 2003: 250-251).

Here is a typical thanking statement that clarifies a PDA’s connection with its

previous, relevant co-text:

14

�Main characteristics

(14) “Finally, for listening, understanding, and providing emotional support, I

gratefully acknowledge my partner […] and friend […]” (Edu5;

identification of the benefactor and list of specific benefits).

Less typical are thanking statements that are somewhat cryptic; e.g.:

(15) “Last but not least, I cannot forget my intramural basketball buddies […]

and […]” (EECS3; leaving the nature of the benefit unmentioned)

(16) “I also thank Martin for giving me the opportunity to live in Lausanne for

half a year” (EECS1; leaving the type of relationship between the

benefactor and the beneficiary to be inferred).

Finally, as an attachment to a text meant for the “general” public (i.e. the

dissertation), a PDA recontextualizes its deictic frame by selecting the

dissertation reader as its official addressee. Thus the PDA realizes its responding

function indirectly, by referring to the writer’s benefactors as part of the subject

matter, rather than addressing them as members of the readership (cf. Hyland

2004: 320); e.g.:

(17) “I thank my wife, Marcia, for her love and unconditional support” (Phys4;

reference to the benefactor in the third person)

(18) “I would like express my sincere gratitude to my advisors […] for their

guidance, help and support […]” (Phys1; reference to the benefactors in the

third person).

The use of address terms or second person pronouns and verb forms applied

to benefactors is attested, but infrequent; e.g.:

(19) “This thesis is partly for you too, Mom and Dad. Thank you” (EECS3; use

of second person personal pronoun and address terms)

(20) “Job well done, Brother!” (EECS2; use of address term)6.

2.3 CONTENT

In terms of content, a PDA may be oriented towards its writer’ and/or her

helpers, more specifically, towards the complementary roles played by these

individuals in previous interactions – as supposedly generous providers and

satisfied receiver, respectively, of services and support. Indeed, the PDA writer

can focus on the roles that others played in the realization of her project, namely

the trouble they went to, which had a beneficial bearing on the final result she

6

Only in Engl3 is the reader referred to rather than addressed: “I can do no more than to refer

the gentle reader to my dedication.”

15

�Acknowledgments: structure and phraseology

achieved and which determined her current indebtedness. At the same time, she

can focus on the effect that those kind actions had on her attitude towards the

benefactors, namely the change in her feelings due to the benefits received (i.e.

her appreciation of the benefactors’ generous behaviour).7 In the former case,

the writer fails to satisfy her desire not to be impeded upon, thus threatening her

negative face; this is because the help received she refers to draws attention to a

limitation on her freedom of action – however welcome – which influenced and

directed her behaviour.8 With the latter option, on the other hand, she is able to

satisfy the benefactors’ desire to be liked and approved of, thus sustaining their

positive face (Brown and Levinson 1987); this is because reference to the

writer’s cognitive-emotional state helps reveal her perception of her benefactors

as agreeable companions she is happy to be around.

The following excerpts show how a PDA-initial statement, or even a micro

introductory move (see section 4.5.1.1), may openly address either interpersonal

aspect of the interaction between the beneficiary and her benefactors:

(21) “To my dissertation committee, I give great thanks” (Edu1; focus on the

expression of grateful feelings)

(22) “I would never have been able to complete this study, were it not for the

persistent encouragement and the support of my professors, friends, and

relatives” (Arch5; focus on the manifestation of indebtedness)

(23) “The joy I feel in having completed this dissertation is accompanied by a

deep sense of gratitude. Traces of the hard work and insight of professors,

friends, and colleagues are legible to me on every page” (Engl4; focus on

the manifestation of gratitude and indebtedness).

The public expression of the author’s feelings motivates the writing up of the

PDA, while the description of the circumstances that caused her indebtedness

justify those feelings to the reader (see sections 2.1 and 2.4.). Together, the

reference to these situational variables – (a) the pleased acceptance (b) of

7

Similarly, in a study on Japanese, Kumatoridani (1999) shows how thanks (for the benefit

received) and apologies (for the trouble caused) can co-occur or alternate within responses to

offers that have been accepted or requests that have been satisfied (see section 3.3.1.2).

8

Her current manifestation of gratitude, too, is determined by the benefactors’ previous

interactional behaviour. More generally, a beneficiary can react indifferently or resentfully,

rather than gratefully, to a benefactor; however, assuming she is abiding by the cooperative

principle, her (verbal) response will always be relevant to, and actually pre-selected by, the

benefactor’s previous interactional move.

16

�Main characteristics

previous offers (c) from previous interlocutors – gives rise to the basic structure

of the text’s main strategic move.

2.4 COMPLEXITY

A PDA is a multi-faceted text. First, it is both a public document and a

private communicative act (cf. Giannoni 1998: 64). On the one hand, it publicly

and officially recognizes others’ professional merits, as its title

Acknowledgements suggests; on the other hand, it informs the reader about

personal circumstances, which are nevertheless made public (see Cronin,

McKenzie, Stiffler 1992: 108);9 e.g.:

(24) “I would especially like to thank my advisor […] for his guidance and

insight. His support and patience were very much appreciated” (Phys2;

focus on the public acknowledgement of benefits)”

(25) “I would like to express my most heartfelt appreciation to my research

advisor, Professor […], for his support, guidance, and encouragement

throughout my doctoral program. His no-nonsense style and persistent

work ethic has always given me something to strive for in my own daily

pursuits – both inside and outside academic circles” (EECS2; focus on the

public acknowledgement of benefits and merits)

(26) “Not only of academia is [sic] possible to survive. Many friends at

Berkeley helped me to conclude. […] These friends and their family

provided the conditions for my family and me to spend unforgettable

moments at Berkeley. My love and gratitude to them all” (Arch2; focus on

the memory of private circumstances)

(27) “[…], the most devoted, selfless and supportive friend one could ask for,

has listened to my cries of joy and pain through times of thick and thin.

[…] is also a walking encyclopedia from whom I can always gather lots of

technical information, career advice, stock insights, and, more recently, HP

gossips” (EECS1; focus on academic and personal circumstances).

In addition, a PDA fulfils a twofold interactional function: on the one hand,

as a delayed move that globally refers to previous (non)-verbal exchanges

similarly oriented towards a common purpose, it completes a larger interaction,

bringing it to an end; on the other hand, as an independent communicative act, it

internally clarifies its connection with the relevant co-text, and creates and

9

Compare also Meier (1989: 34) about private acts of thanking appearing in the press.

17

�Acknowledgments: structure and phraseology

completes a distinct interactional event. A PDA is thus both a complementary

and an autonomous unit of communication; e.g.:

(28) “Many people have helped me in the writing of this dissertation. […] I

regret that I can offer, in return for all this help, no more impressive

evidence of my gratitude” (Phil1; focus on bringing a larger interaction to

an end: a discontinuous, introductory-and-concluding AM)

(29) “It has been a long journey and there have been so many people who were

encouraging and helpful along the way. […] Mom, Dad – I finished!”

(EECS1; focus on bringing a larger interaction to an end: text-initial

introductory move and text-final concluding move)

(30) “The writing of a dissertation is a long and sometimes lonely task, and it is

hard to recognize everybody who contributed to this work. However, some

people stand out” (Stat1; introductory move stressing the self-contained

nature of the PDA)

(31) “My work has benefited from conversations with colleagues, former

teachers, and new acquaintances. For their generous help, I am grateful to

[…]” (Phil2; clarifying the connection of the PDA with its relevant co-text)

(32) “I am further indebted to Mr. […] for carefully reviewing the draft of this

dissertation, and for his invaluable comments on both technical contents

and English writing” (EECS4; clarifying the connection between the PDA

and the relevant co-text).

It therefore appears that a PDA establishes a one-to-many relationship with

previous discourse. Although it is one self-contained text realizing a distinct act

of communication, it is oriented towards several previous interactional events.

This accounts for its cyclical internal arrangement, that is, the recursiveness of

its basic functional component, the AM (see section 2.6.1); in this respect, the

PDA can be viewed as an integrated collection of mini-texts; e.g.:

(33) “[#1] I would like to thank my doctoral advisor […] for financial support

and for his guidance during the completion of the research project. [#2] I

am indebted also to […] for their advice and their insightful comments on

the manuscript. [#3] Thanks also to […] for their friendship, for many

discussions early on in the project, and for always being willing to help me

find an answer to my questions. [#4] I am grateful to my colleagues at the

[…] for many interesting scientific discussions, and especially for their

encouragement and support when things went wrong. [#5] Thank you very

much to my father […] for all the encouragement and for teaching me that

there were no limits to what I could be. [#6] Thank you to […] my friend

18

�Main characteristics

and first real science teacher, for always being close in spite of the distance.

[#7] Finally, special thanks to […] for introducing me to the world of

photosynthesis, for his continuous support and countless discussions on the

experimental part of the project, and for sharing with me his never-ending

enthusiasm for science” (P-Bio1; a 7-AM long PDA)10

(34) “[#1] I’d like to thank my advisor […] for his guiding hand and help over

the last two years. “THANKS!” [#2] Thanks also to my fellow graduate

students, particularly […] for listening to my musings, rhetorical questions

and other types of ‘thinking aloud’. [#3] Finally I’d like to gratuitously

[sic] acknowledge the […] for accepting a softball novice into the fold. [//]

[#4] The research in this thesis was partially supported by […] grants […].”

(Stat3; a 4-AM-long PDA).11

The connection between a PDA and its co-textual dissertation, is also

complex, but in a different way. On the one hand, a PDA is concretely bound to

its dissertation and partly relevant to it content-wise (i.e. it concerns the writer’s

work seen as an on-going process and related as in a narrative); also, it partly

adopts the dissertation’s deictic frame, by identifying the you of the message

(i.e. the intended recipients of the text) in the readers of the dissertation, while

the benefactors become part of the subject matter (this way, the PDA is partly

anchored to a contextual property of the dissertation; cf. Hyland 2003: 244; see

section 2.2); e.g.:

(35) “I thank the members of my committee […] I have learned much from each

of them, and I admire their wisdom and enthusiasm. They have done their

best to share both with me” (Econ1; third person plural personal pronouns

and possessive referring to a group of benefactors)

(36) “Finally, I want to thank […] for her support, patience and love […]” (BAdm2; a third person singular possessive referring to a single benefactor)

(37) “[…] was one of these persons to be remembered forever. He was a

member of my doctoral exams and a member of my dissertation committee.

I knew […] through his work with the community and with minorities. I

was invited to his Design Studio class to comment on the work of his

students. From then on we developed a relationship which helped me to

understand better the struggles of the peoples of the USA. He taught me a

10

Here and elsewhere, the symbol [#] signals the beginning of a new AM. For the criterion

adopted for the identification of AMs, see section 4.2.

11

Here and elsewhere, double slashes signal the beginning of a new paragraph.

19

�Acknowledgments: structure and phraseology

great deal […]” (Arch2; third person singular personal pronouns and

possessives referring to a single benefactor).

At the same time, a PDA is conceptually removable from its dissertation,

given its distinct communicative purpose – showing deference to the benefactors

and/or enthusiasm for the benefits rather than reporting and discussing the

author’s independent achievement of academic results. Also, content-wise, a

PDA is highly relevant to the author herself as a social individual in a network

of personal and professional relationships. As a result, the PDA partly

contradicts the dissertation it accompanies – it reveals the author’s dependence

on others with regard to a project requiring (and a report stressing) the author’s

confidence and self-reliance (see Giannoni 1998: 76-77). Therefore, the PDA is

simultaneously and ambiguously inward- as well as outward-oriented (see BenAri 1987: 63; Hyland 2003: 244; Hyland 2004: 305), that is, relevant both to the

individual research project reported in the dissertation – carried out by the

author on her own – and to the circumstances of the project reported in the PDA

itself – which involved others’ help; e.g.:

(38) “I wish to thank […] for all of their help with confocal microscopes” (PBio2; focus on the author’s dependence on others)

(39) “I feel lucky to be able to work in the […] Center and the Department of

Plant Biology in UC Berkeley, which are two of the most dynamic and

stimulating environments in the field of plant biology. […] I would like to

express my deepest appreciation to the […] Foundation and the

International House in UC Berkeley, which provided me with the support

to continue my graduate studies. […] Above all, endless love and thanks to

my parents, all my sisters and my brother for their encouragement,

unconditional support and love. Their love is the source of power that

keeps me going throughout the years” (P-Bio3; focus on the author’s

network of professional and personal relationships)

(40) “My fellow students, especially […], and the […], have been of invaluable

help during my struggles, have provided many stimulating arguments and

discussions, and have filled any excess time with fun” (Stat2; focus on the

author’s network of relationships and dependence on others).

Also, given that a PDA is a delayed manifestation of thanks – its relevant cotext consists of spatio-temporally remote interactional events – the gratitude it

expresses may be worded in such a way that it has a primary, but not necessarily

absolute, performative value. That is to say, AMs in a PDA do realize a

conclusive series of current acts of thanking through expressions of thanks

20

�Main characteristics

relevant to the present (and, much more rarely, to the future); however, they may

also refer to previous ones (e.g. when thanking expressions mention the writer’s

past cognitive-emotional state towards her benefactors and/or benefits; see

Giannoni 1998: 73); e.g.:

(41) “First, I thank my qualifying committee […]” (Phys2; realization of a

current act of thanking)

(42) “I would like to thank my advisor […] for his support and for his boundless

enthusiasm. He introduced me to the exciting and beautiful world of cell

biology, and for that, I will be eternally grateful” (P-Bio2; realization of a

current act of thanking and reference to a future one)

(43) “As a foreign student in America, I was blessed to make many remarkable

friends in the I-House who helped me to learn about the American culture

and society. I cannot imagine a better start in a strange land than the IHouse” (P-Bio3; reference to the author’s positive perception of her past

beneficial state in relation to her benefactors and/or benefits)

(44) “It was a great pleasure to work with so many undergraduate assistants”

(P-Bio5; reference to the author’s previous positive cognitive-emotional

state towards her benefactors)

(45) “I have been blessed with a family which values higher education” (Engl3;

reference to the author’s positive cognitive-emotional state experienced in a

span of time extending from the past into the present).

Furthermore, a PDA deals with the notion of ‘exchange’ in two

complementary ways: as a topic to be discussed and a function to be realized.

On the one hand, the PDA author talks about benefactors’ past acts of giving to

her (i.e. offers of goods, services and/or information); on the other, she carries

out an act of giving to the readers (and non-informed benefactors), that is, she

offers information about previous exchanges she was involved in and her

feelings in response to those exchanges. For this reason, a PDA enacts a role

reversal in the interaction; e.g.:

(46) “The University of California, Berkeley, and the Bay Area more generally,

have given me ample intellectual community” (Engl3; giving information

to the reader about a service received from benefactors)

(47) “and the Center for the Health Professions for the hospital data” (Econ1;

giving information to the reader about a service received from benefactors).

Finally, although the expression of the writer’s grateful attitude towards her

benefactors is the communicative goal that defines the essence of the PDA as a

21

�Acknowledgments: structure and phraseology

global act of thanking, this does not necessarily mean that gratitude is the most

prominent notion in the text. Indeed, the writer’s need to make her text

understandable to a readership potentially wider than her helpers may lead her to

focus on a description of her benefactors and benefits, and to marginalize or

even omit the expression of thanks. Therefore, the textual means to the end of

thanking may highlight the subsidiary meanings, not the primary concept, of the

PDA. It is precisely the rich description of benefactors and benefits, rather than

feelings, attested in the corpus (see sections 4.2.1, 4.6 and 4.7), that may turn an

act of thanking into an extended speech act or even a speech act set (Cohen and

Olshtain 1981); e.g.:

(48) “[…] has not only been a supportive mentor but a good friend as well. We

have had many personal conversations which I did not imagine possible

with an advisor, and she has given many [sic] invaluable advice on my

personal life” (EECS1; focus on benefits)

(49) “I have made many special friends […] who have made grad school such a

unique and exciting learning experience. You know who you are, so I will

not list your names here because, well, it’s just not my style. Being in

Berkeley or Lausanne has been a transient period for many of us, and some

of you have already left, and so have I. Fortunately, since most of us are

engineers, it is likely that we either stay in or converge to the Silicon

Valley, so there will be lots more chances to take trips or hit the bar scenes

together” (EECS1; focus on background information and opinions)

(50) “First of all, I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my advisor

Professor Chenming Hu for his guidance and support given to me

throughout my study in Berkeley. His keen insights, stimulating advice,

and incredible patience toward my research have shown me what a top

professor should be. It has been a special privilege to be his student. This

unique experience will be a source of long lasting inspiration to me”

(EECS4; focus on benefactors and benefits).

2.5 GENRE STATUS

After Swales (1990) and Bhatia (1993), I consider a non-fictional genre a set

of spoken or written utterances that are produced in and shaped by habitual

interactional events recognizable by members of a given socio-linguistic

community. These units of communication answer recurrent interpersonal

and/or instrumental needs through a partial or exclusive use of language; in the

former case, they may accompany given interactional events (e.g. minidialogues in service encounters), while in the latter case, they constitute the

22

�Main characteristics

interaction itself (e.g. e-mail exchanges of news). The fact that they are similarly

function-oriented and ratified within a specific cultural group leads to the

establishment of conventional procedures for their production, distribution, and

use as well as to the development of their shared characteristics (i.e. in structure,

content, and style). Indeed, they can be called a genre (i.e. a kind of kind)

precisely because it is possible to identify and abstract from them a group of

shared properties and generalize them into a category or type. That is, they are

recognized as repeated occurrences of the “same” communicative situation or as

repeated communicative situations perceived to be similar.

PDAs conform to the above-mentioned properties and thus constitute a

genre: they are communicative acts meant to realize a common, basic

interactional function which, in turn, shapes their content and form (see sections

2.1 and 2.3). Swales’s (1990) criteria for identifying and describing genres are

suitable for characterizing PDAs as well.

(I) “A genre is a class of communicative events” (p. 45; original emphasis).

PDAs are communicative events in the sense that language plays “both a

significant and an indispensable role” in them (p. 45). It is totally through verbal

interaction that their authors express their feelings and satisfy their benefactors’

positive face needs (see section 2.3). PDAs also constitute a class of

communicative events because they can be easily recognized and labelled within

the discourse community in which they are exchanged. The interactional

occasion that sets the stage for their production and reception and the role they

play for the participants involved are familiar to the members of that

community. As a result, their common properties stand out prominently in the

professional domain in which they are used.

The following PDA illustrates the above observations: it is completely

realized through language; it is accompanied by a descriptive label (i.e. its title);

it is recognizable by its title (i.e. Acknowledgements) and content (i.e. reference

to the benefits the writer received from her helpers and manifestation of the

writer’s relevant gratitude); and its content explains why it has been produced:

(51)

“Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my dissertation committee members […] and […]

for invaluable guidance and suggestions. I am also indebted to […] and

[…] for their many helpful comments. I would also like to extend my

appreciation to […] and […] for making my time here so memorable” (BAdm4; an exemplar of the PDA genre; original bolding).

23

�Acknowledgments: structure and phraseology

(II) “The principal criterial feature that turns a collection of communicative

events into a genre is some shared set of communicative purposes” (p. 46;

original emphasis). PhD candidates write to achieve a communicative goal,

namely, the manifestation of a positive attitude towards the supportive people

who helped them during the completion of their dissertation projects. This

shared purpose both identifies PDAs as a genre and determines their typical

content – expression of their writers’ gratitude, description of the benefits

received, and reference to the benefactors to be credited for them.

However, PDAs may include additional information and/or satisfy related

purposes that sustain their main function. That is, they may expand on their

basic information units with details that help the reader contextualize – and

appreciate the value of – the relationship or interactions between the writer and

her helpers. The main act of thanking may thus be supported, for instance, by

apologies for disturbing benefactors, compliments on their excellence or offers

of repayment for services received; e.g.:

(52) “My thanks also go to Kaye Bock who helped me produce this manuscript

in its final form” (Arch1; reporting circumstances motivating the writer’s

gratitude)

(53) “I would like to thank my wife […] for being the unique human being she

is and for waiting relatively patiently for me in […] while I spent countless

hours working on this dissertation which could have been spent with her

instead” (Stat 1; referring to the cost of the benefit to the benefactor)

(54) “I owe a profound debt to my dissertation advisors […]. Each of them has

provided the right combination of timely encouragement and

knowledgeable criticisms which have saved me from many blind alleys.

Time and time again I have been amazed by their truly extraordinary

dedication and by their incisive readings of Spinoza” (Phil 5; expanding on

the qualities of the benefactors)

(55) “This is equally true for […], who never lost faith in this dissertation. I am

grateful to her for reading every single draft with extraordinarily rigorous

attention. I count our (almost daily) exchange about my dissertation précis

during the fall of 1996 to be one of the most transformative intellectual

events of my graduate career. Indeed, the central arguments for the

dissertation emerged out of this exchange. Throughout the writing process

– and during that fall especially – I learned from her how to envision whole

arguments from seemingly disparate close readings. I will continue to strive

to incorporate into my work the lessons I learned from her then. It is hard

24

�Main characteristics

to imagine how she has the time to do as much for her students as she does,

but I hope I will be able to find a similar reserve in guiding my own

students through their projects. She will certainly always remain a model

of pedagogy for me.

I hope that I can bring to my own dissertation students what I have learned

from each member of my dissertation committee about the rewards of

rigor, the pleasures of scholarship, and the spirit of intellectual community”

(Engl4; expressing the will to reciprocate the benefits).

(III) “Exemplars or instances of genres vary in their prototypicality” (p. 49;

original emphasis). Genre exemplars are not clones of one another: new ones are

produced whenever new interactional occasions arise, and even if the

interactions in question are of the same kind, they will be distinctly relevant to

their specific context. This means that each genre exemplar reproduces its genre

differently, and therefore that some communicative acts represent the genre they

are members of more typically than others. How typically they instantiate the

genre depends on how many privileged vs. marginal features (see Rosch 1973,

1975, 1978) of the genre they exhibit and on whether they align with just one

genre or more (see Bhatia 1994 about genre mixing and embedding).

The main privileged property of a genre is the communicative purpose

shared by its members, which motivates their instantiation and makes them

recognizable. Other important properties of the genre exemplars – relatable to a

shared communicative purpose – are their form, content and structure, and the

audience expectations about them. Marginal properties include the genre

members’ length, degree of elaboration, subsidiary topics, instrument of

communication and linguistic code. When such features are similarly

instantiated across exemplars, they stress the conventionality of the genre.

A good genre member thus partly reproduces and partly innovates its genre:

on the one hand, it instantiates its relevant text type and observes the most

recurrent conventions of the socio-cultural community in which it is produced

(so that it can be easily recognized by the addressee as a token of a given type);

on the other, it unambiguously shows its relevance to its specific context of

situation (so that it can be appropriately used by all the participants involved).

The properties PDAs are expected to share include their authors’ intention of

manifesting appreciation for help received (purpose), reference to the authors’

interactions with their benefactors (content), organization in conceptual

paragraphs each focusing on one (group of) benefactor(s) (structure), tone

typical of a partly public and partly private communicative act, i.e. half way

between formal and informal (form), and awareness of the partial overlap

25

�Acknowledgments: structure and phraseology

between the authors’ benefactors and the dissertation readers (audience

expectations).

A prototypical PDA is characterized by several properties. First, it is

recognized as an instantiation of the type of communicative act meant to convey

the writer’s positive feelings towards her benefactors with regard to her

dissertation project. Also, it is oriented toward the higher-level goal of

sustaining temporarily unbalanced social relationships: the benefits exchanged

between the dissertation writer and her helpers have turned the former into a

debtor and the latter into creditors, but the PDA gives the writer the opportunity

to show that she is aware of the situation and to start giving something back,

namely good feelings. Moreover, it satisfies its readers’ expectations in four

respects: it selects as its addressees the readers of the dissertation in which it is

included rather than the writer’s helpers; it includes information about the latter

that might not be accessible to the former; also, it reveals that the dissertation in

question was the result of a joint effort, that is, a project coordinated by the

writer, but not entirely carried out by her; finally, it manifests the writer’s

sincere good will towards her benefactors as a result of help received. Finally, a

PDA shows some creativity “despite” its recognizability: the text’s partly

original contribution to the genre both contributes to the latter’s internal

variation (i.e. vitality) and provides evidence of the writer’s individual, distinct

experience (i.e. relevance to specific interactional circumstances).

In sum, a typical PDA gives due prominence to the text type shared with

other texts reproducing similar content, reveals its writer’s awareness of her past

dependence on and current indebtedness to her benefactors, and provides

background information about the writer’s previous interactions so that its

readers can make sense of the writer’s manifestation of gratitude; e.g.:

(56)

“Acknowledgements

I would like to thank […] and […] for their valuable suggestions,

comments and time. I would also like to thank the […] for providing

financial assistance and access to […] data during my fellowship there.

The comments and opinions in this dissertation are my own and do not

necessarily reflect those of the directors, members, or officers of the […].

I am very grateful to many professors and colleagues for interesting

discussions and for guidance during the last few years. In particular, I

would like to thank […] and […] for helpful conversations and

assistance. I would like to thank my family for their encouragement and

support from the start. Lastly, I would like to dedicate this dissertation to

26

�Main characteristics

the memory of […] who shared his enthusiasm towards investigating new

ideas with me” (B-Adm1; a typical PDA; original bolding)

(57)

“Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the members of my committee: […]. Their comments

on this project were unfailingly incisive, thought-provoking, and

encouraging; their scholarly works were models and inspirations to me.

Thanks, also, to […] whose comments were very helpful to me at

different stages of the dissertation. […] was that great teacher who first

inspired my interest in and love of eighteenth-century literature.

My personal debts are too many to pay off here. Thanks to the friends

who helped me through, and especially to […] who kept me smiling this

last year. My parents were an unfailing support. And of course, […]

makes it all worthwhile” (Engl1; a typical PDA).

Atypical instances of the genre could be PDAs having the outer appearance

of an acknowledgment, but not written in the true spirit of grateful good will,

which would make their genre membership questionable. None of the PDAs

examined contradicts its communicative purpose. And indeed, failure to adhere

to the genre’s pivotal property is likely to undermine the specific genre

member’s communicative effectiveness, “popularity rating” and social success.12

The content of PDAs can be dismissed as unimportant only as long as they

reproduce a culturally ratified pattern of communication, in which no

participant’s face is deliberately or seriously threatened. Thus, mock offence and

irony can be tolerated, and backhanded comments are acceptable, if they reflect

well on the benefactor; e.g.: