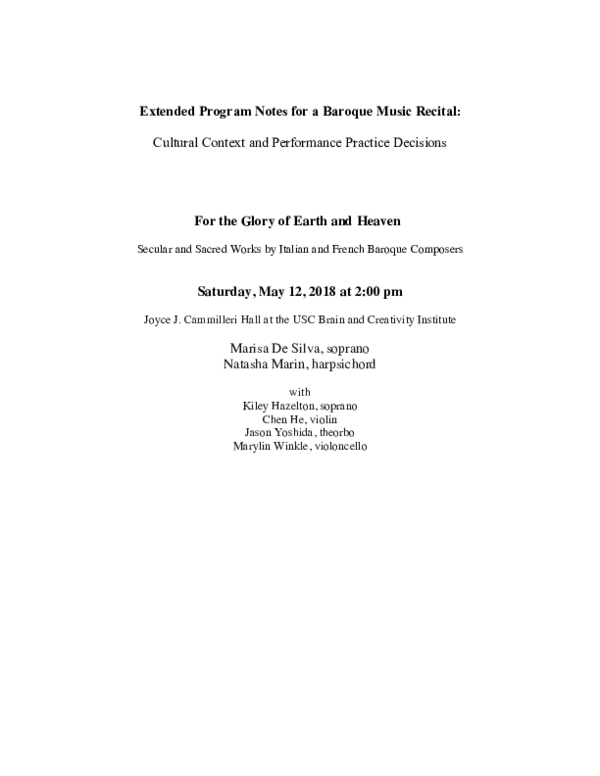

Extended Program Notes for a Baroque Music Recital:

Cultural Context and Performance Practice Decisions

For the Glory of Earth and Heaven

Secular and Sacred Works by Italian and French Baroque Composers

Saturday, May 12, 2018 at 2:00 pm

Joyce J. Cammilleri Hall at the USC Brain and Creativity Institute

Marisa De Silva, soprano

Natasha Marin, harpsichord

with

Kiley Hazelton, soprano

Chen He, violin

Jason Yoshida, theorbo

Marylin Winkle, violoncello

�Program

Secular

Girolamo Frescobaldi

(1613-1643)

Michel Lambert

(1610-1696)

Giovanni Legrenzi

(1626-1690)

Claudio Monteverdi

(1567-1643)

Se l’aura spira

Cosi mi disprezzate

Vos mépris chaque jour

Par mes chants tristes et touchants

Le repos, l’ombre, le silence

Tout l’univers obéït à l’amour

“Lumi potete piangere” from Venere sopra un scoglio

Kiley Hazelton, soprano

Jason Yoshida, theorbo

Quel sguardo sdegnosetto

Zefiro torna

Kiley Hazelton, soprano

Marylin Winkle, violoncello

Jason Yoshida, theorbo

Intermission

Sacred

Jean-Joseph Cassanéa

de Mondonville

(1711-1772)

Girolamo Frescobaldi

(1613-1643)

Louis-Nicolas

Clérambault

(1676-1748)

selections from Pièces de clavecin avec voix ou violon op.5

1. Regna terrae, Cantate Deo

5. Paratum cor meum

Chang He, violin

“Balletto-Corrente-Passacagli” from Toccata d’intavolatura

Maddalena alla Croce

Gloria in excelsis Deo, C.99

�Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643)

Claudio Monteverdi's output, including madrigals, sacred works and operas, is integral to

our understanding of late Renaissance and early Baroque music. For this program we present two

works from his madrigals.

Monteverdi spent his early years in Cremona, Italy, where his art “was nurtured in a musical

environment that was more conservative than experimental,” in contrast to later in his career at

the Gonzaga court in Mantua (1590-1613) where he “went on to accomplish some of the most

important early advances in the development of opera.” (Buelow, 2004, 57) Together with his

brother Cesare, Claudio Monteverdi contributed to the creation of seconda prattica. In the 1607

publication of Claudio’s Scherzi Musicali the brothers included a Declaration that became “one

of the most famous manifestos in the history of Western music.” (Atlas, 1998, 619) They

proposed a change in the hierarchal relationship between words and music from the earlier

principles of prima prattica where counterpoint played a dominant role (exemplified by

Zarlino’s 1558 Istitutioni harmoniche) to a new compositional approach, such as madrigals of

Cipriano de Rore, where “harmony does not rule but is ruled, and the words are the mistress of

the harmony.” (ibid.) Monteverdi spent the last decades of his life (from 1613 until his death in

1643) in Venice where he held a prestigious appointment as Maestro de Capella of the Basilica

of S. Marco. It “forced a shift in his professional commitments away from court music in favor

of the church,” (Whenham, 2007, 179) but he still produced a limited amount of secular music

for important social events for which he was able to choose artistic collaborators. (Stevens, 1980,

402)

Quel sguardo sdegnosetto and Zefiro torna are from the collection Scherzi musicali ciel

�aire, madrigali et ciaccona SV. 247. It was published in 1632 and provides an example of

Monteverdi’s writing for solo voice during the late Venetian period.

Quel sguardo sdegnosetto (No.2) was written to the text of Bartholomeo Magni, a

Venetian printer who became the most active re-issuer of Monteverdi’s earlier secular works and

the editor of his later ones. (Bornstein, 2012, 6) Defined in Monteverdi’s time as “aria,” this

piece is a setting of strophic text for solo voice and continuo. It consists of three stanzas

connected by instrumental ritornelli, with a changing strophic vocal line over the same bass. The

printed vocal line has few written out melodic elaborations and no markings for ornaments. To

help with performance practice decisions for this piece and similar 17th century repertoire,

singers often turn to Caccini’s Le nuove musiche (1602), which, for the first time, codified

ornaments and explained appropriate context for their use. Based on Caccini’s rules, one of the

examples of ornament addition in our interpretation is the use of trillo on the last cadence of the

piece for the word riso (laughter) that enhances expression of the text.

Zefiro torna (No.9) is a ciaccona for two voices and continuo. It is a setting of Ottavio

Rinuccini’s text that was inspired by Petrarch’s sonnet of the same title which Monteverdi set for

five voices in his Book VI of madrigals in 1614. While the continuo part repeats a two-measure

ground bass, Monteverdi takes full advantage of the text’s imagery to employ traditional wordpainting technique. The florid and virtuosic vocal lines are complete, with all elaborations

written out by the composer. They depict “mountains” with ascending leaps in one voice, while

the other voice moves in the opposite direction to portray “the valleys; ” “murmuring” is set to a

wavy melodic lines, appogiaturas are used for “accents,” and a canon for “hair braided with

garlands.” (Carter, 2002, 424)

In both pieces, the continuo part consists only of the bass line, without other voices or

�figures to indicate the harmonies. Many of Monteverdi’s contemporaries were openly opposed to

the use of figures, (Arnold, 1965, v.1, 66) but such practice inevitably led to potential problems

for performers both in the past and in the present. As Francesco Bianciardi (1607) warned,

“because if the consonances that have to be played aren’t written above the basses, and if the

player doesn’t know the art of counterpoint or doesn’t have great experience in playing by ear,

he will easily do more harm than good to the composition.” (8) To help remedy the situation,

several treatises published at the beginning of the 17th century in Italy explained the fundamental

rules of thoroughbass. These authors emphasized a proper knowledge of counterpoint and

experience as major factors contributing to good musicianship and also provided some important

practical guidelines that help us recreate performance practice of the day. The earliest source of

such guidelines is a preface of Lodovico Viadana’s Il cento concerti ecclesiastici published in

1602. Among twelve points pertaining to performance practice, the second one is about the

relationship between the vocal and basso continuo lines, stating that if the accompanist “wants to

make some movements with the upper hand, as to florish the cadences, or some passages at

occasion, he has to play such that the singer or the singers do not get covered or confused by too

much motion.“ (6) This recommendation was corroborated in 1607 by Agazzari in the treatise

Del sonare sopra’l basso con tutti li stromenti. Agazzari classified keyboard instruments as

fundament, which guide and support the entire sound of all voices, as opposed to ornament

instruments, “those ones which by counterpoint make the sound of the harmony more

agreeable.” (5) Agazzari advised that “if there are much voices one must play full and double the

stops. But if there are little one must reduce and play only little consonances; playing the piece

more clearly and correctly, if possible without passages or arpeggios; but adding some double

basses and avoiding mostly the high parts since these are normally taken by the voices, mostly

�sopranos and falsettos.” (ibid., 9) Another very important point is about the use of major third in

cadences. “All the cadences, either middle or final, desire a major third, but some people do not

sign them. But for better security, I advise you to put the figure, especially at the cadences in the

middle.” (9) Some rules about proper voice leading can be found in Bianciardi’s 1607 Breve

Regola per imparar’a sonare sopra il Basso con ogni sorte d’Instrumento. When talking about

direction of voices, he emphasized that, “above all, because the harmony is born from different

sounds ordered in contrary motion, it is important to ensure that when the Bass rises, another part

descends; and that when it descends, that another part rises.” (7) All the above mentioned as well

as additional resources were used in making performance practice decisions for our concert.

Text and Translations

Zefiro torna

Zefiro torna e di soavi accenti

Return O Zephyr, and with gentle motion

l’aer fa grato e’il pié discioglie a l’onde make pleasant the air and scatter the grasses in waves

e, mormoranda tra le verdi fronde,

and murmuring among the green branches

fa danzar al bel suon su’l prato i fiori.

Make the flowers in the field dance to your sweet sound.

Inghirlandato il crin Fillide e Clori

Crown with a garland the heads of Phylla and Chloris

note temprando lor care e gioconde;

with notes tempered by love and joy,

e da monti e da valli ime e profound

from mountains and valleys high and deep

raddoppian l’armonia gli antri canori.

and sonorous caves that echo in harmony.

Sorge più vaga in ciel l’aurora, e’l sole, The dawn rises eagerly into the heavens and the sun

sparge più luci d’or; più puro argento

fragia di Teti il bel ceruleo manto.

scatters rays of gold, and of the purest silver,

like embroidery on the cerulean mantle of Thetis.

Sol io, per selve abbandonate e sole,

But I, in abandoned forests, am alone.

l’ardor di due begli occhi e’l mio tormento,

The ardour of two beautiful eyes is my torment;

come vuol mia ventura, hor piango hor canto.

As my Fate wills it, now I weep, now I sing.

�Quel sguardo sdegnosetto

Quel sguardo sdegnosetto

That haughty little glance,

lucente e minaccioso,

bright and menacing,

quel dardo velenoso

that poisonous dart

vola a ferirmi il petto,

is flying to strike my breast.

Bellezze ond'io tutt'ardo

O beauties for which I burn,

e son da me diviso

by which I am severed from myself:

piagatemi col sguardo,

wound me with your glance,

Sanatemi col riso.

but heal me with your laughter.

Armatevi, pupille

Arm yourself, o eyes,

d'asprissimo rigore,

with sternest rigor;

versatemi su'l core

pour upon my heart

un nembo di faville.

a cloud of sparks.

Ma 'labro non sia tardo

But let lips not be slow

a ravvivarmi ucciso.

to revive when I am slain.

Feriscami quel squardo,

Let the glance strike me;

ma sanimi quel riso.

but let the laughter heal me.

Begl'occhi a l'armi, a l'armi!

O fair eyes: to arms, to arms!

Io vi preparo il seno.

I am preparing my bosom as your target.

Gioite di piagarmi

Rejoice in wounding me,

in fin ch'io venga meno!

even until I faint!

E se da vostri dardi

And if I remain vanquished

io resterò conquiso,

by your darts,

feriscano quei sguardi,

let your glances strike me –

ma sanami quel riso.

but let your laughter heal me.

�Monteverdi. Quel sguardo sdegnosetto

�Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643)

Girolamo Frescobaldi’s works include a variety of vocal and instrumental compositions;

however, his fame and legacy were founded on his skills as a keyboard player and his

contribution to the keyboard repertoire. (Anderson, 1994, 35) Frescobaldi spent his early years in

Ferrara where he absorbed musical influences of the court of Alfonso II d’Este. Praised from an

early age for his musical talent, Frescobaldi had the opportunity to develop under the guidance of

Luzzasco Luzzaschi, a keyboard virtuoso and composer at the service of Duke Alfonso. Through

the influence of Luzzaschi, who studied with Cipriano de Rore, Frescobaldi was exposed to both

the idiomatic keyboard style and the seeds of seventeenth-century seconda prattica, a style that

originated in works by Rore and Luzzaschi and was further developed by Monteverdi.

(Hammond, 1983, 10) Other influences included Ferrarese and visiting musicians, such as the

renowned vocal group Concerto delle donne, Gesualdo de Venosa, Luca Marenzio, Claudio

Merulo and John Dowland. (idib., 9) After leaving Ferrara, Frescobaldi held (with some

interruptions) the position of organist at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome from 1608 until his death.

Balletto-Corrente-Passacagli are from the appendix of small pieces added to the 1637

reprint of the first book of Toccate d’intavolatura di cimbalo et organo (first published in 1616

in Rome by Nicolo Borbone). While Toccatas fully demonstrate Frescobaldi’s mastery of the

keyboard style with variety of textures, rhythms, embellishments, large sectional organization,

and expressive figurations, Balletto-Corrente-Passacagli exhibit simpler writing and no marked

or written out ornamentations. Valuable remarks on proper performance can be found in the four

prefaces to Frescobaldi’s keyboard works published in 1615, 1616, 1624 and 1635. (Hill, 2005,

56)

�Se l’aura spira, Cosi me disprezzata and Maddalena alla croce are from Primo libro

d’arie musicali per cantarse published in 1630 during several years that Frescobaldi spent in

Florence (1628-1634). As Hammond (1983) noted, the content of the book “is an indication that

Frescobaldi had traveled far from the musical tradition of Ferrara.” (77) The arie of the

collections fall into four main categories: works in continuous recitative style, arie entirely in

melodic style (either strophic or with written-out stanzas), works mixing the two styles, and

settings on bass-patterns. (ibid., 265)

Sonetto spirituale Maddalena alla croce may have been inspired by the 1618 Maddalena

chiedendo a pie del duro legno of Andrea Falconieri. It exemplifies Frescobaldi’s treatment of

recitative style, with a melodic line that follows the rhythm of the text and a special emphasis

added to affective words by melodic or harmonic inflections. (ibid.) Se l’aura spira represents

another category, an aria in entirely melodic style with written-out varied stanzas. Cosi me

disprezzate, an Aria di passacaglia, demonstrates a different approach to the passacaglia pattern

than some of Frescobaldi’s earlier publications. Here, he enhanced emotional variety of text by

treating an ostinato pattern with great freedom and allowing different figurations and

substitutions. The dramatic triple meter sections based on the passacaglia pattern are juxtaposed

with free recitative. (ibid., 214)

�Text and Translations

Maddalena alla croce

A pié della gran croce, in cui languiva

At the foot of the great cross on which lay

Vicino a morte il buon Giesù spirante,

Good Jesus in agony, close to death,

Scapigliata così ppianger s’udiva

His faithful and desolate lover,

La sua fedele addolorata amante.

Her hair disheveled, was heard to weep.

E dell’humor, que da’begli occhi usciva

India or Atlas, as long as life has existed,

E dell’or della chioma ondosa, errante

have never delivered pearls or gold finer

Non mandò mai, da che la vita è vita

than the tears that fell from her fair eyes

Perle, od oro più bel l’India, ò l’Atlante.

Or the gleam of her wavy and scattered locks.

Come far (dicea) lassa, ò Signor mio,

‘O my Lord,’ she said, ‘how can you

puoi senza me quest’ ultima partita?

make this final departure without me?

Come morendo tù, viver poss’io?

How can I live, if you die?

Che se morir pur vuoi, l’anima unita

‘If you truly wish to die, my Reeemer, my God,

Ho teco (il sai, mio Redentor, mio Dio)

my soul, as you know, is joined with yours;

Però teco haver deggio e morte, e vita.

With you I must share both death and life.’

�Se l’aura spira

Se l’aura spira tutta vezzosa,

When the breeze blows most sweetly

La fresca rosa ridente stà

And the fresh rose stands smiling

La siepe ombrosa di bei smeraldi

The shady hedge of emerald green

D’estivi caldi timor non hà

Has no fear of summer’s heat

A’balli, a’balli liete venite Ninfe gradite,

Come, come and dance, you nymphs

fior di beltà, Or che sì chiaro

So light and charming, flowers of beauty;

il vago fonte

Now that the stream, clear and fair,

Dall’alto monte al mar sen và

Makes its way from the mountains to the sea.

Suoi dolci versi spiega l’augello,

The birds deploy their sweet songs

E l’arbuscello fiorito stà

And the flowering bushes are covered in bloom;

Un volto bello all’ombra accanto,

Let one fair face alone, close by the shade,

Sol si dia vanto d’haver pietà

Be proud of having shown compassion.

Al canto, al canto ninfe ridenti,

come, come and sing, you laughing nymphs,

Scacciate i venti di crudeltà

And drive away the winds of cruelty.

�Così mi disprezzate

Così mi disprezzate?

Così voi mi burlate?

Tempo verrà,

ch’amore farà di vostro core

Quel, che fate del mio,

Non più parole, addio!

How can you spurn me so?

How can you make fun of me like this?

A time will come

when love will do to your heart

what you are now doing to mine.

Not a word more, farewell!

Datemi pur martiri,

burlate i miei sospiri,

negatemi mercede,

oltraggiate mia fede,

ch’in voi vedrete poi

quel che mi fate voi.

Cause me great suffering,

mock my sighs,

deny me mercy,

outrage my faith,

for then you will see in yourself

what you are doing to me.

Beltà sempre non regna,

E s’ella pur v’insegna

a dispregiar mia fè,

credete pur a me,

che s’oggi m’ancidete

doman vi pentirete.

Beauty does not always reign;

If it should lead you

to despise my faith,

then believe this:

If you should kill me today,

you would repent of it tomorrow.

Non nego già ch’in voi

Amor ha i pregi suoi,

ma sò ch’il tempo cassa

beltà che fugge, e passa

Se non volete amare,

Io non voglio penare

I do not deny that

love’s prizes dwell in you,

but I know that time pursues

fugitive and transient beauty.

If you do not wish to love,

I do not wish to be hurt.

Il vostro biondo crine

le guance purpurine

veloci più che maggio

tosto saran passaggio

Prezzategli pur voi

ch’io riderò ben poi.

your blond hair

and crimson cheeks

will pass and be gone

more rapidly than the month of May.

Treasure them greatly,

For I shall laugh well later.

�Frescobaldi. Balletto-Corrente-Passacagli

�Giovanni Legrenzi (1626-1690)

�Giovanni Legrenzi was a prominent 17th century composer in Northern Italy. Born

near Bergamo, he later spent a decade working there as an organist. The second half of his career

took place in Venice where he eventually became Maestro di cappella at S. Marco. Legrenzi was

“a major contributor to opera and sacred music,” composed “significant instrumental music”

(Buelow 2004,108) and was “the most important composer of oratorio working in Venice during

the latter part of the 17th century.” (Anderson, 1994, 87) Out of Legrenzi’s nineteen operas,

which were extremely popular during the composer’s time, only a few survive to our day.

One of these surviving operas is La divisione del mondo, which was commissioned by

Marquis Guido Rangoni. It was set to the libretto by Giulio Cesare Corradi and premiered in

1675 at the Teatro San Salvador in Venice. The opera was immensely successful in part due to

the use of elaborate stage machinery, dazzling visual effects, and expensive costumes. It went

through more than a dozen productions before the end of the 17th century. (Nagler, 1959, 269)

Lumi potete piangere is the opening scene of the third act of the opera. It is written on an ostinato

bass repeating descending chromatic line, a quintessential musical representation of the lament.

Text and Translation

Lumi, potete piangere

Lumi, potete piangere

Eyes, you can cry

non riderete più

you don’t laugh anymore.

Il cor che lieto fu

The heart which used to be happy,

nel duol si sente à frangere

in grief feels it heartbroken.

Lumi, potete piangere

Eyes, you can cry.

Legrenzi. Lumi, potete piangere

��Michel Lambert (1610-1696)

Michel Lambert was an influential musician of his time, respected as a composer and

sought after as a performer and singing teacher. He started working at the court of Louis XIV in

1651, and later served as a Maitre de Musique de la Chamber du Roi. While Lambert’s output

includes ceremonial music, the greater part of his work consists of airs de cour (court airs). This

genre started to develop in France in the late Renaissance and became a predominant type of

secular composition in the courts of Louis XIII and Louis XIV. Airs de cour were typically

performed in an intimate setting, such as in a drawing room or a small outdoor concert. By the

second half of the 17th century, their form was well established as a setting of a text almost

invariably consisting of love poetry for a solo voice and basso-continuo. Typically, airs consisted

of two stanzas: the first simple and slow moving, to present the text as clearly as possible, while

the second served as a virtuoso display, with a faster tempo, written-out diminutions and very

little harmonic or melodic connection to the first section. (Caswell,1968, ix)

The four airs in this program, Vos mépris chaque jour, Par mes chants

tristes et touchants, Le repos, l’ombre, le silence and Tout l’univers obéït à l’amour, are

from the 1689 manuscript of the collection Sixty airs for voices and continuo.

Alternative versions of these airs for a different number of voices are preserved in 1689

publication by Ballard. Tout l’univers it is a setting of a poem by Jean de la Fontaine

(1621-1695) from the 1669 collection Les amours de Psyche. The lyrics of the other three

airs are by anonymous authors. The vocal part is fully written out with several markings

for ornamentation, and the accompaniment is given as a figured bass, a practice that

became well established outside Italy by the middle of the 17th century.

Michel Lambert did not provide a chart of ornaments, nor did he leave any

�theoretical writing. But we know from the composer’s contemporary accounts that his

music was praised for its grace and elegance, as well as sensitivity for declamation. In

his vocal works he allowed the text to unfold in a natural manner. (Sadler, 2002, 620)

One of the most important writers on the airs de cours vocal style is Benigne de Bacilly (16251690), whose work is especially significant in the area of the French ornamentation. (Caswell,

1968, vii) In his 1668 treatise Remarques curieuses sur l’art be bien chanter (A commentary

upon the art of proper singing), Bacilly referenced many of Lambert’s airs to demonstrate the

proper realization of ornaments. While giving many examples of where adding ornaments and

diminutions is appropriate, Bacilly emphasized that “The object of a good singer is always to

preserve the expression of the words, and this is accomplished by permitting certain appropriate

part of the melody to be sung in their simple form.” (ibid., 106)

Though Bacilly favored theorbo as the accompanying instrument, he also listed the

harpsichord and the viol as possible alternatives, even though they “haven’t the grace and

accommodation found in the theorbo.” (ibid., 11) Several sources are available to harpsichordists

to assist them with decisions about texture, position, register and arpeggiation of the chords,

doubling of the melody or bass notes, rhythmic alterations and ornamentation. The primary

theoretical sources closest to the airs in our program are: Guilliame-Gabliel Nivers’ L’art

d’accompanger sur la basse-continue pour l’orgue et le clavecin (1689); Jean-Henry

d’Anglebert’s Les Principes de l’accompangnement from Pieces de clavecin (1689) ; Denis

Delair’s Traite d’accompagnement pour le theorbe, et le clavecin (1690); and Saint Lambert’s

Les Principes du clavecin (1702 ) and Nouveau traite de l’accompagnement de clavecin, de

l’orgue ,et des autres instruments (1707).

With some exceptions, there seems to be a preference for texture with bass in the left

�hand, three note chords in the right hand and a contrary motion of the hands (Fuller, 1989, 122;

Saint Lambert, 1707, 58). In chord progressions it is advised that “the accompaniment should

always move by the smallest intervals possible-and sometimes not move at all.” (ibid.)

Considering the possibilities offered by the “short-octave” that became popular at the end of the

17th century and the extensive use of the low register in solo keyboard repertoire, it’s possible to

occasionally double bass notes an octave lower. Discussion of ornamentation plays an important

role in all the treatises; although “the trend of the day, as corroborated by Delair and

d’Anglebert, was towards a richly textured and florid basso continuo,” (Mattax in Delair,

1991,12) Delair emphasized that, “It is out of the question to allow the instrument to stand out

when accompanying; rather, one should only support the voice one accompanies.” (ibid.,68)

Text and Translations

Vos méspris chanque jour

Vos méspris chanque jour

Your scorn each day

me causent mille alarmes,

causes me a thousand alarms,

mais je chéris mon sort,

yet I cherish my fate,

bien qu’il soit rigoureux:

though it is severe:

Hélas! Si dans mes maux

Alas! If in my ills

je trouve tant de charmes,

I find so many charms,

je mourrois de plaisir

I would die of pleasure

si j’estois plus heureux.

if I were happier.

�Par mes chants

Par mes chants

By my songs

tristes et touchants,

sad and touching,

vous connoisse: Iris

you know, Iris,

la douler qui me presse:

the pain that is pressing me:

Mes ennuis sont cruel,

My troubles are cruel,

rien ne peut les bannir,

nothing can banish them,

et je ne chante pas

and I do not sing

pour charmer ma tristesse,

to charm my sadness,

mais plustonst pour l’entretenir.

but more to maintain it.

Le repos, l’ombre, le silence

Le repos, l’ombre, le silence

The rest, the shadow, the silence,

Tout m’oblige en ces lieux

Everything obliges me in these places

À faire confidence

to speak

de mes ennuis les plus secrets.

of all my most secret worries.

Je me sens soulagé dy conter mon martyre,

I feel relieved by recounting my agony,

je ne le dis qu’à des forets;

I am only telling it to the forests;

mais, enfin, c’est toujours le dire.

but telling it nonetheless.

Tout l’univers obeït à l’Amour

Tout l’univers obeït à l’Amour,

All the universe obeys Love:

Belle Phillis, soumettez-lui votre âme.

Beautiful Phyllis, submit your soul to it,

Les aitres dieux à ce dieu font la cour,

the other gods court this god,

et leur pouvoir est moins doux que sa flamme.

and their power is lesser than his flame.

Des jeunes coeurs c’est le supreme bien,

For young hearts, it is the supreme good,

Aimes, aimez; tout le reste n’est rien.

Love, love; all the rest is nothing.

Lambert. Par mes chants tristes et touchants

�Louis-Nicolas Clérambault (1676-1748)

�Louis-Nicolas Clérambault first established a reputation as an organist at the service of

Madame de Maintenon, the second wife of Louis XIV. After her death, he continued to work at

the school for young girls from poor nobility that she founded, The Maison Royale de SaintLouis, where he was responsible for the organ, composing music, and directing choir. It was

during that tenure that he developed his vocal compositional style. Clérambault gained greatest

success and popularity with his cantate francaise (French chamber cantatas) (Buelow, 2004,

185), characterized by simplicity, gentle inflexions, ornamental subtlety, and delicacy of

expression. (Anderson, 1994, 171)

Hymne des anges gloria in excelsis Deo, C.99 is from the first book of Motets for one,

two, and three voices composed between 1712 and 1745. Its manuscript is located at the

Bibliothèque Nationale de France. The contrasting sections of this motet exhibit some of

Clérambault’s characteristic features present in his cantatas and are also related to French

tradition of representing emotions in music. Emotions, or passions as they were called during

Baroque era, played very prominent role in French arts and rhetoric. In his 1649 treatise Les

Passions de l’ame (The passions of the soul), René Descartes explained the nature of

fundamental passions and classified them as either agitated, modest, or neutral. (Gordon-Seifert,

2011, 61) These categories also applied to the musical representation of the passions by

composers. (ibid., 64) Primary passions, such as le desespoir (despair), le pouvoir (power,

courage), les feux de l’amour (burning love), la douleur (sorrow or pain), la langueur (languor),

la douceur (tenderness), and le contentement (happiness) dominated French 17th century vocal

repertoire and were given special musical treatment. (ibid., 60) The opening and closing sections

of Gloria exhibit features corresponding to the representation of le contentement, such as the

major mode and regular rhythm. The slow lyrical sections in the middle are examples of la

�douceur characterized by the minor mode, bass line moving by seconds, and melodic contour

comprised of short motives that imitate sighs. (ibid., 95)

Text and Translation

Glória in excélsis Deo

Glória in excélsis Deo

Glory to God in the highest

et in terra pax homínibus bonæ voluntátis

and on earth peace, goodwill to all people.

Laudámus te,

We praise thee,

Benedicimus te,

we bless thee,

Adoramus te,

we worship thee,

Glorificamus te,

we glorify thee

grátias ágimus tibi propter

we give thanks to thee

magnam glóriam tuam,

for thy great glory.

Dómine Deus, Rex cæléstis,

Lord God, heavenly King,

Deus Pater omnipotens.

God the Father Almighty;

Dómine Fili unigénite, Jesu Christe

Lord, the only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ,

Dómine Deus, Agnus Dei, Fílius Patris,

Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father,

qui tollis peccáta mundi,

that takest away the sins of the world,

miserére nobis;

have mercy upon us,

qui tollis peccáta mundi,

Thou that takest away the sins of the

súscipe deprecatiónem nostram.

world receive our prayer.

Qui sedes ad déxteram Patris,

Thou that sittest at the right hand of the Father,

miserére nobis.

have mercy upon us.

Quóniam tu solus Sanctus, tu solus Dóminus,

For thou only art holy’ thou only art the Lord;

tu solus Altíssimus, Jesu Christe.

Thou only, Christ, with the Holy Ghost,

cum Sancto Spiritu, in Glória Dei Patris.

Art most high in the glory of God the Father.

Amen.

Amen.

Clérambault. Hymne des anges gloria in excelsis Deo

�Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville (1711-1772)

�Jean-Joseph de Mondonville moved from the south of France to Paris in his early

twenties. There he established himself among leading musical figures by gaining the patronage

of Madame de Pompadour and entering into the service of Louis XIV. A brilliant violinist, he

held several important posts, including those at the Chapel Royal and at the Concert Spirituel,

the first public concert series in Europe. He was equally successful in dramatic, instrumental, and

sacred compositions, with his grands motets earning him a post of Maitre de musique de la

Chapelle. Mondonville was a younger contemporary of another dominant figure of the High

French Baroque, Jean-Philippe Rameau, and the works of the two composers were often

compared during their lifetime. One of Mondonville’s most important contributions was the

introduction of obligato (written-out) keyboard parts. (Cyr, 2015, 1) As opposed to the

previously dominant practice where continuo accompaniment was improvised from the bass,

Mondonville’s Pieces de Clavecin en sonates avec accompagnement de violon published in 1738

contained a fully written-out keyboard part with a violin accompaniment. In 1741, Rameau

acknowledged Mondonville’s sonatas as inspiration for the publication of his own Pièces de

clavecin en concerts, harpsichord pieces with violin (or flute) and a viol (or a second violin).

This new genre that “ushered the keyboard sonata into France,” (Anthony, 1997, 309) became

increasingly popular in Europe and England and is considered a precursor to the piano trios and

quartets of the Viennese classics. (Cyr, 2015,1)

Regna terrae, cantate Deo (no.1) and Paratum cor meum (no. 5) are from the

Pièces de clavecin avec voix ou violon op.5 published in 1748. It is a collection of nine sacred

motets for harpsichord with violin or soprano voice set to Psalm texts. It is possible that the

collection was written for Anne-Jeanne Boucon whom Mondonville married that year. AnneJeanne was a student of Rameau and a talented harpsichordist and singer who could perform

�keyboard and vocal parts, while the optional violin part could be played by Mondonville.

(Marchand, 2007, 11)

In the foreword to the publication, Mondonville provided an ornament chart, performance

practice instructions, and suggestions on how to best approach learning the pieces to “overcome

all difficulties.” He recommended to first work on Paratum (no. 5) or Benefac Domine (no.3)

and to study the parts separately starting from the vocal line. That should help the performer to

“observe with attention” all the details and ornaments that the composer “took care to mark,” and

also “to distinguish in turn the phrases which are in the French taste,” with more syllabic

passages with short ornaments, from “those which demand the Italian taste,” with more virtuosic

texture of longer passages sung over a single syllable. The title “Pieces for harpsichord with

voice or violin” is explained as follows: “I felt that this arrangement would be of particular

interest to people who combine talent on both harpsichord and voice, since they could perform

this type of music alone. People who play the harpsichord but who have no voice could have the

vocal part played on violin. In the absence of both violin and voice, the accompaniment alone

will suffice.” Hence, none of the motets have any sections where violin and voice are written

together as harmony. Considering the density of the texture and profusion of ornaments, the next

line is of importance: “When the voice, the violin, and the harpsichord are united (which is

possible between two persons), the sound of the voice and the violin should be proportioned to

the strength of the harpsichord, so that each part is distanced.” In accordance with the

composer’s instructions, in our performance, we strive for a balance between vocal, violin, and

harpsichord parts and avoid simultaneously doubling the melody in all parts.

Text and Translations

�Regna terrae, cantate Deo

Regna terrae, cantate Deo,

Your kingdoms of the earth, sing to God,

Psallite Domino.

Sing psalms to the Lord.

Psallite Deo, qui ascendit

Sing psalms to God, who has ascended

Super caelum caeli ad orientem.

Over the heavens in the east.

Paratum cor meum

Paratum cor meum Deus,

My heart is prepared, O God,

Cantabo, et psalmum dicam.

I will sing songs, and I will always sing praise.

Mondonville. Regna terrae, cantate Deo

��Bibliography

Agazzari, Agostino. Del Sonare Sopra’l Basso Con Tutti Li Stromenti, 1607

http://www.bassus-generalis.org (Accessed 2/1/2019 )

Anderson, Nicholas. Baroque Music. New York: Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1994

Anthony, James R. French Baroque Music From Beaujoyelx To Rameau. Portland: Amadeus

Press, 1997

Arnold, Franck Thomas. The Art Of Accompaniment From A Thorough-Bass As Practised In The

17th and 18th Centuries. New York: Dover Publications, 1965

Atlas, Allan W. Renaissance Music. New York: W. W. Norton and Co., Inc., 1998

Bianciardi, Francesco. Breve Regola Per Imparar'a Sonare Sopra Il Basso Con Ogni Sorte

D'Instrumento, 1607 http://www.bassus-generalis.org (Accessed 2/1/2019)

Bornstein, Andrea, ed. Claudio Monteverdi Scherzi Musicali Ciel Aire, Madrigali In Stil

Recitativo, Con Una Ciaccona A 1 Et 2 Voce. Archive of Seventeenth-Century Italian

Madrigals and Arias, 2012

http://epapers.bham.ac.uk/1677/1/Monteverdi_Scherzi_1632_Complete_Edition_rev1.pdf

(Accessed 2/1/2019)

Buelow, George John. A History Of Baroque Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press

2004

Caccini, Giulio. The New Music. H. Wiley Hitchcock, ed. Middleton, Wisconsin: A-R Editions,

Inc., 2009

Carter, Tim. ‘Two Monteverdi Problems, And Why They Matter’. The Journal Of Musicology

19, no.3 (2002) : 417-433

�https://www-jstororg.libproxy1.usc.edu/stable/10.1525/jm.2002.19.3.417?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_conte

nts

(Accessed 2/6/19)

Caswell, Austin B. A Commentary Upon The Art Of Proper Singing By Benigne De Bacilly

(1668). Netherlands: Koninklijke van Gorcum and Co., 1968

Cyr, Mary. ‘Origins And Performance Of Accompanied Keyboard Music In France’. Musical

Times 156, no. 1932 (2015)

https://www.questia.com/magazine/1P3-3872517131/origins-and-performance-ofaccompanied-keyboard-music

(Accessed 2/4/2019)

Delair, Denis. Accompaniment On Theorbo And Harpsichord. Translation and commentary by

Charlotte Mattax. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991

Fuller, David. ‘The Performer As Composer’. In Performance Practice: Music after 1600,

Howard Mayer Brown and Stanley Sadie, eds. Ch. 6. New York and London: W.W.

Norton and Co, 1989

Gordon-Seifert, Catherine. Music And The Language Of Love. Bloomington and Indianapolis:

Indiana University Press, 2011

Hammond, Frederick. Girolamo Frescobaldi. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University

Press, 1983

Hill, John Walter. Baroque Music. New York: W.W. Norton and Co. Ltd., 2005

Marchand, Guy. Mondonville’s Opus 5 Pièces De Clavecin Avec Voix Ou Violon. Translated by

Peter Christensen. 2007

https://www.analekta.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/AN%202%209920.pdf

(Accessed 2/4/2019)

Nagler, Alois Maria. A Source Book In Theatrical History. Massachusetts: Courier Corporation,

1959

�Sadler, Graham. ‘The Neglected Michel Lambert’ Oxford University Press 30, no. 4 (2002) :

619-620

http://www.jstor.org/stable/3519220

(Accessed 2/1/2019)

Saint Lambert. Principles of The Harpsichord By Monsieur De Saint Lambert. Translated and

edited by Rebecca Harris-Warrick. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984

Saint Lambert. A New Treatise On Accompaniment With The Harpsichord, The Organ, And With

Other Instruments. Translated by John S. Powell. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana

University Press, 1991

Stevens, Denis. The Letters of Claudio Monteverdi. New York: Cambridge University Press,

1980

Viadana, Lodovico. Il Cento Concerti Ecclesiastici, 1602. http://www.bassus-generalis.org

(Accessed 2/1/2019)

Whenham, John and Westreich, Richard, eds. The Cambridge Companion To Monteverdi. New

York: Cambridge University Press, 2007

�

Natasha Marin

Natasha Marin