Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 608–629

Research Article

Julia Skala*

The Present Perfect Puzzle in US-American

English: an FDG Analysis

https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0030

Received May 11, 2018; accepted August 17, 2018

Abstract: This paper examines the rare but well-attested combinations of the Present Perfect with definite

temporal adverbials denoting past time in US-American English. The goal of this paper is twofold. For one

thing, it outlines the disemous analysis FDG proposes for the form have + past participle in its prototypical

use, arguing that two different operators can reliably trigger this form, one marking anteriority and one

encoding phasal resultativeness. For another, it shows how, via synchronic inferential mechanisms, the

Present Perfect may have absorbed discourse pragmatic functions that now permit the felicitous use of

definite temporal adverbials together with the Present Perfect in certain contexts. It is argued that this

combination has routinized, taking over certain functions typically associated with the Present Perfect in

a manner that suggests this development as potentially part of a grammaticalization process. The paper

proposes that they are not as such part of the function the Present Perfect encodes, but that they currently

represent a switch stage in the development of the US-American Present Perfect. It further suggests that

in this switch stage, the combination of the Present Perfect with an adverb specifying past reference can

be read as signaling the relationship between two Discourse Acts as justificational or can encompass the

temporal specification as a necessary part of the action that is then available for a Resultative reading.

Keywords: Present perfect, US-American English, Context-induced reinterpretation, Grammaticalization,

Functional Discourse Grammar, tense, Adverbials of time

1 Introduction

In the rich literature on the English perfect, and the Present Perfect (PrP) in particular, Jespersen (1931: 61) was

one of the first to look at this tense-aspect combination also in terms of the adverbials of time it can or cannot

co-occur with, considering them an important element in a speaker’s choice to use the PrP rather than another

form. In his paper, Klein (1992) coined the memorable term “the Present Perfect Puzzle” for the apparent

incompatibility of the English PrP with definite temporal adverbials (dtAdvs) like yesterday or last week, in

other words with those temporal adverbials that he classifies as “specify[ing] the position of a time span on

the time axis” (1992: 528). From a semantic point of view, this restriction is indeed a puzzle; why should the

PrP, which is clearly used for events that have occurred in the past, be incompatible with information on when

in the past said event took place? Linguistic reality shows that this restriction clearly exists, however, and it is

stressed as well as integrated into the respective theories they work with by Declerck (2006) and Klein (1992),

as well as many others (e.g. Comrie 1976; Pancheva and Stechow 2004; Rothstein 2008).

In this, these authors are not completely unjustified, of course; in the clear majority of cases, the PrP

is not anchored in time by means of dtAdvs (such as, for example, two days ago or in 1995). However,

Article note: The paper belongs to the special issue on Systems of tense, aspect, modality, evidentiality and polarity in Functional

Discourse Grammar, ed. by Kees Hengeveld and Hella Olbertz.

*Corresponding author: Julia Skala, University of Vienna, E-mail: julia.skala@univie.ac.at

Open Access. © 2018 Julia Skala, published by De Gruyter.

NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-

�The Present Perfect Puzzle in US-American English: an FDG Analysis

609

researchers who have conducted corpus studies on the use of the PrP (e.g. Schlüter 2002; Hundt and Smith

2009; Werner 2014) have found that, while comparatively infrequent, such combinations do occur. Their

stable presence is noted across time (e.g. Hundt and Smith 2009) as well as variety (Werner 2013) and genre.

While quite a number of researchers therefore agree with Rastall’s (1999: 81) assertion that, quite possibly,

these combinations “are not ‘errors’ or the products of non-standard speakers”, little headway has since

been made regarding the circumstances that license these co-occurrences.

Interest in this matter is growing, however, especially where Australian English is concerned. Engel and

Ritz (2000) propose a meaning extension for the Australian PrP, among other reasons because of the form’s

co-occurrence with dtAds. They initially based this proposal on their findings in spoken data, but Ritz

(2010) has since been able to corroborate this, using written data from Australian police media reports. She

concludes that, at least in narrative Australian English, the PrP can have two reference times, one of which

is the point in time at which the event took place, which permits a variety of “inferred readings, such as

mirative, indirective and evidential” (Ritz 2010: 3415), and thus is open to temporal modification by dtAdvs.

Richard and Rodríguez Louro (2016) build on these findings and show that, quite surprisingly, it is rather

older men who use the combination of PrP + dtAdvs in Australia, suggesting that this meaning extension

is not a recent one, but rather a marginal but long-established phenomenon that has only recently caught

linguists’ interest.

Walker’s conclusion on the use of the PrP, especially by British footballers (2008), initially followed

a similar path. He proposed a narrative function for the PrP in British English that might have a long,

understudied history (Walker 2011). While the narrative PrP itself does not function in combination with

dtAdvs, it might then have served as a basis for analogy for PrP sentences with a dtAdv. Recently, however,

he has called this into question, since he could find little evidence of its existence before the mid-nineteenth

century (Walker 2017). He now tentatively concludes that it might represent an intermediate stage between

the perfect and the aorist (Walker 2017: 35).

The present paper intends to add to this body of research by making a foray into a third variety,

that of US-American English. The aim of the paper is twofold. First, it aims to contribute to the work in

Functional Discourse Grammar by laying out an FDG analysis of the English PrP in its various uses, based

on attested examples from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA, Davies 1990–2015)1. In

this, it underlines the clear difference between the Anterior operator and the Resultative operator, as the

Anterior operator, expressing relative tense, can only apply to arrangements with multiple States-of-Affairs

(SoA) within an Episode, whereas the Resultative operator, expressing phase, can also (and mainly does)

act on a single Configurational Property. Second, the paper makes use of the different components and

levels of FDG to offer an interpretation of the co-occurrence of the PrP form with dtAdvs in US-American

English. Using Giomi’s (2017) proposal, this paper shows how a stronger integration of the Contextual

Component can help account for the context-induced reinterpretation of the PrP, which, in turn, opens

the form up for modification by a dtAdv. A central suggestion put forth in this paper is that a distinction

needs to be made between those cases where the dtAdv constitutes an integral bit of information for a

successful interpretation of the utterance and those were it does not. In the case of the first group, the

function that triggers the PrP interacts much more closely with the dtAdvs. This is especially typical for

the many restrictive relative clauses found in the dataset. Where the dtAdv does not play such a role, two

interpretations suggest themselves. Considering the change in function the ‘have + past participle’ form

has undergone in other languages of the world (cf. e.g. Bybee et al. 1994; Hengeveld 2011; Gelderen 2011),

a possible development towards a perfective gram (as defined by Bybee et al. 1994: 54), or a full past tense

marker could in theory be proposed. The data set analyzed for this study, however, rather suggests that

it might be the discourse-pragmatic inference (cf. Nishiyama and Koenig’s “common sense entailment”

[2006: 273]) that semantisizes and allows the dtAdv modification in specific contexts.

1 The COCA is a balanced corpus of contemporary US-American English consisting of roughly 20 million words from each year,

evenly divided between the five genres it contains mark-up for, namely academic journals, newspapers, magazines, fictional

texts and spoken language (for the most part from TV talk shows and radio programs), courteously provided online by Mark

Davies and his team at Brigham Young University (BYU).

�610

J. Skala

The article is organized as follows: After a brief sketch of previous work on the English PrP in Section 2,

focusing on two linguistic phenomena that are particularly relevant for the present analysis – the functions

of the English PrP, and, in combination with this, the role of adverbials – Section 3 lays out an analysis of

the PrP within the framework of FDG. Particular attention is paid to the different functions with regard

to the operators and modifiers at the respective layers. Section 4 then discusses the data that is at the

heart of this paper, namely the COCA examples where speakers combine the PrP with dtAdvs. The data is

categorized into two groups by the difference in contextual inference they allow for. Making use of Giomi’s

(2017) application of Heine’s (2002) context-based model of grammaticalization, the internal make-up of

these different groups of combinations of dtAdvs and the PrP is discussed. Section 5 concludes the article.

2 The English Present Perfect – a brief overview

An account of previous work conducted on the PrP must, by necessity, be selective; giving but a brief

overview, Davydova alone named more than thirty different publications on this form in her 2011

monograph, and many have since been added to this impressive body of research (cf. e.g. Werner et al.’s

“extensive ‒ -yet, in all probability, still not exhaustive ‒ literature review of newer works” [2016: 7]). This

section, therefore, limits itself to a discussion of the two elements most central to the following analysis,

namely that of the number and kinds of functions that can be encoded using the PrP and the role played by

the temporal adverbials in the clause.

Regarding the PrP’s function, one central matter of contention is that of the number of different

meanings the PrP has. For a table detailing ten different categorization schemes as well as their more than

30 different proponents, see Werner (2014: 72), who lists approaches ranging from as few as one central one

(e.g. also Comrie 1976) to as many as five (e.g. Walker 2008). Those authors who postulate only one meaning

for the PrP do not deny the versatile nature of the PrP, but rather refer to them as uses and relate them all

back to one central function. Declerck, for example, clearly identifies one central underlying meaning,

stating that “[t]he semantics of the Present Perfect is therefore: ‘The situation time is located in the prepresent zone of the present time sphere’” (2006: 212), but at the same time also identifies four different

‘readings’ for the form. Other advocates of the monosemous view have selected one of various different

senses as the central one. Palmer, for example, postulates that the superordinate meaning of the PrP is

“that in some way or other […] the action is relevant to something observable at the present” (1974: 50),

similar to Comrie, who identifies “the continuing relevance of a past situation” (1976: 52) as the epitomical

sense of the PrP.

These definitions hinge on an almost intuitive understanding of rather opaque concepts. The ‘prepresent zone’ is not clearly delineated from the past-zone by any other means than its being viewed as the

time span stretching towards the moment of speech (Declerck 2006: 109) and thus defined in relationship

to speech time, whereas, presumably, the past time-zone is not (Declerck 2006: 146–147). Declerck himself

to an extent concedes this difficulty, and assigns the difference to the choice the speaker makes regarding

“temporal focus” (Declerck 2006: 150)

This, Declerck (2006: 110) actually links to the other opaque concept to be addressed here, that of

‘current relevance’. While, according to Werner (2014: 62), the notion of current relevance is one of the oldest

and most prevalent meanings ascribed to the PrP, it has also repeatedly been questioned as a semantic

principle due to its inherently subjective nature (e.g. Fleischmann 1983: 191–192; Binnick 1991: 382; Wynne

2000: 168). A case has been made for this notion to, in fact, be a pragmatic rather than a semantic one (e.g.

Binnick 1991: 459; Rastall 1999: 83; Werner 2014: 65). Then, however, it becomes difficult to ascribe this to

the PrP in particular. Presumably, on a pragmatic level, an addressee expects a speaker to adhere to Grice’s

Maxim of Relation and therefore assumes her “contribution to be appropriate to immediate needs at each

stage of the transaction” (Grice 1975: 47) in any case (cf. also Harder 1997: 382 and Werner 2014: 64).

What has often been termed the “classic analysis” of the English PrP (e.g. Miller 2004: 230) is actually

a four-way split of the PrP functions, as shown in (1), based on Comrie (1976: 56–61):

�The Present Perfect Puzzle in US-American English: an FDG Analysis

611

(1) a. Experiential Perfect

Sara has danced here before.

b. Perfect of Result

You won’t be able to see Sara. She has already danced.

c. Perfect of Continuous/Persistent2 Situation

Sara has danced here for two years now.

d. Perfect of Recent Past

Sara has just danced.

(1a), the “experiential perfect” is closely related to Declerck’s pre-present reading discussed above. (1b), the

“perfect of result” constitutes a very prototypical instantiation of a current relevance (cf. also Elsness 1997:

68). The third function of the PrP, that of encoding that the situation referred to is a “persistent situation”,

suggests that the described event or situation continues at speech point. Lastly, there is the rather selfexplanatory “recent past”. This fourth type is listed here for completeness sake only; in US American

English the Past Simple has largely replaced the PrP in these instances (cf. e.g. Panzner 1995: 146), which is

why it will not receive any further attention in this paper.

While the different meanings encoded by the sentences in (1) a–d, and thus the different functions of

the PrP, may appear obvious at first glance, a closer look calls this classic categorization into question. Note,

for instance, that if one strips these sample sentences of their contextualizations and temporal adverbs, it

would be very difficult to distinguish between these four meanings (cf. observations that go as far back as

e.g. Crystal 1966).

Using the adverbs ever and yet for the Experiential and the Resultative function respectively, Miller

(2000: 334–335) makes a similar point, and argues that “[t]he perfect construction in itself is vague and

signals only that the speaker focuses on the consequences of some past action. The adverbs make it clear

which interpretation is intended” (Miller 2000: 335). This is inarguably true for the sentences in (1) and any

other such set of sentences provided in isolation and meant to illustrate different functions encoded by the

PrP. At the same time, however, it clearly leaves something to be desired. While, indeed, a comparatively

high percentage of sentences in the PrP include an adverbial of time,3 the majority of them still does not.

If addressees could not infer the meaning contribution of the PrP in these cases, this would be rather

problematic from a communicative point of view.

The fact that temporal adverbials in general co-occur comparatively frequently with the PrP and their

meaning contribution is perceived by some as essential to an understanding of a given PrP sentence, or

overlapping with a central function of this form, can quite plausibly be accounted for within the framework

of Construction Grammar. The frequent occurrences of certain adverbials in clauses containing the PrP

can be argued to provide comparatively concrete lexical meanings that are then associated with the PrP to

an extent that the PrP itself carries these meanings even without the lexical modifications present. What

cannot be answered that way, however, is how many different constructions to postulate then, if it is frequent

co-occurrence with certain lexical items, the meaning of which is adopted by the construction, that determines

the senses of the PrP. There are more than four sets of such adverbials, many of which lend themselves to

different readings because of their inherent ambiguity (cf. Quirk et al.’s [1985: 195] discussion of I have seen

him once [my emphasis]), or because of the generally open interpretation of the function of the clause as a

whole. A sentence like (2), for example, can be assigned either a Resultative or a Continuative meaning.

(2) a. I have always spoken out regarding my life experiences, women’s issues and the need to bring a faster

and more decisive shift in the collective consciousness that will help bring about true women’s equality.

(COCA, magazine)

2 ‘Continuous’ and ‘Persistent’ will be used interchangeably throughout the paper.

3 In his comparison of various corpus studies, Schlüter (2006: 143) demonstrates that there is some variation between corpora

when it comes to temporal specification of the PrP, but that anything from 34% to 45% of the PrP sentences are modified by an

adverbial, compared to only 2% of sentences in Past Simple.

�612

J. Skala

Presumably, the state described, that of the speaker generally speaking out when it comes to his

experiences, women’s issues, and the need for social change still holds. However, at the same time there is

an implied result. In this case, the speaker argues that he is an adamant advocate of women’s rights and,

therefore, would never lay a hand on a woman who did not give her consent to do so, which becomes clear

when one considers the preceding co-text in (2b).

(2) b. “[…] Let me be crystal clear and very direct. Abusing women in any way shape or form violates the very

core of my being,” he said. “I have always spoken out regarding my life experiences, women’s issues

and the need to bring a faster and more decisive shift in the collective consciousness that will help bring

about true women’s equality. […]” (COCA, magazine)

This clearly apparent overlap between senses, together with the fact that no formal differences can be

described between the four classic readings, serves as basis for an analysis of the PrP in FDG that conflates

the four meanings described by Comrie (1976: 65–61). Taking the restrictions regarding the use of the form

as a basis for distinguishing between different senses, FDG arrives at a disemous description of the PrP,

which will be discussed in the following section.

3 The English Present Perfect in FDG

So far, the English PrP as such has not received detailed attention in FDG. Being a textbook on FDG rather

than a description of the English language, A Functional Discourse Grammar for English (Keizer 2015)

mentions, but naturally does not discuss in any detail, how this form is triggered. On the Morphosyntactic

Level (ML), the past participle affix in combination with the auxiliary have in Present Tense (and, thus,

the PrP) is said to be triggered by the “absolute tense operator ‘present’ + phasal aspect operator ‘perfect’”

(Keizer 2015: 238). Said phasal operator is described as “indicating the result or relevance of a SoA that

started in the past” (Keizer 2015: 144).

While Hengeveld and Mackenzie (2008) also mention a phasal operator in this context, namely

one called “Resultative” (Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2008: 211), they analyze the form have heard in the

sentence As for the students, they have heard the news already in terms of “the auxiliary verb have [being]

the expression of the operator Ant(erior) in the presence of a higher episodical tense operator Pres(ent)”

(Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2008: 417). In part, this seems to actually correspond to their description of

the Resultative Aspect, which they describe as the SoA “having happened before the reference point”

(Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2008: 211), even if its name suggests a function similar to the phasal operator

‘Perfect’ described by Keizer. She, in turn, – while clearly not excluding an application to present Episodes

– illustrates the relative tense operator ‘ant’ in connection with past Episodes only (Keizer 2015: 144; 238).4

Connolly on the other hand proposes that the phasal quality “[r]esultative, centered upon the

retrospective phase of the event” (Connolly 2015: 7) is in fact mainly an issue of conceptualizing a SoA as

such, an act that he assigns to what he calls the Conceptual Level (CL). In doing so, he takes the process

of conceptualization, which in standard FDG is seen as prelinguistic in nature (cf. e.g. Hengeveld and

Mackenzie 2008; Keizer 2015), to the linguistic plain. This conceptualization then, together with the overlap

of the SoA in question with a point in time that is not the event time, leads to an insertion of the ‘ant’

operator on the Representational Level (RL), which then, in turn, brings about the morphosyntactic form of

the PrP in the encoding process, according to Connolly (2015: 12–13).

The present section is dedicated to clarifying the FDG analysis of the English PrP by bringing together

the various operators and modifiers that can be seen as playing a role in triggering the morphosyntactic

form have + past participle in English (summarized in Table 1).

4 This is not to say that she in any way suggests that the combination of a Present Tense operator on the level of the Episode

with the Anterior operator on the level of a SoA would be unlikely. I do, however, find it indicative of the notion that, possibly,

this combination, while natural from a typological point of view, might not come readily with English as the language of analysis in mind.

�The Present Perfect Puzzle in US-American English: an FDG Analysis

613

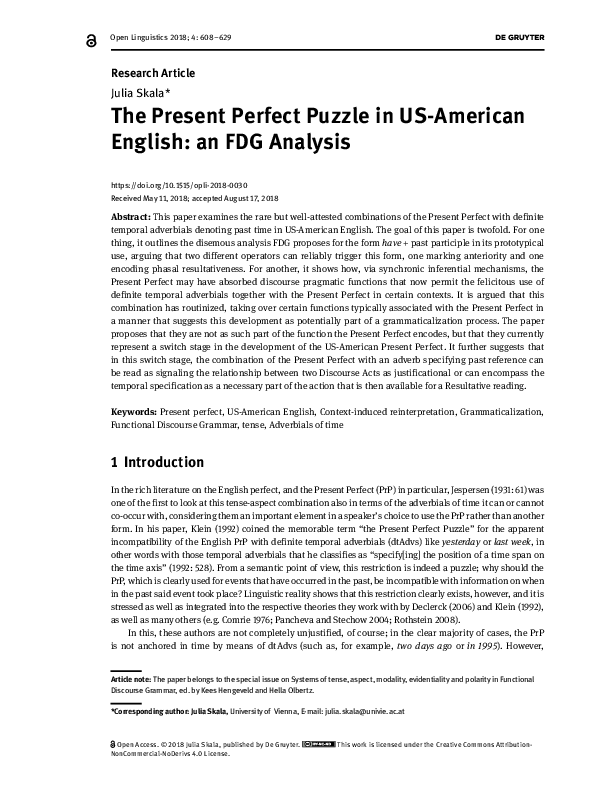

Table 1. Overview of operators, modifiers and discourse functions relevant in a discussion of the English PrP in FDG

REPRESENTATIONAL LEVEL

Layer

Operators

Episode (ep)

SoA (e)

Configurational

Property (fc)

Absolute Tense:

Modifiers

Absolute Time:

in 1993 (calendric)

now (deictic)

when ... (non-deictic)

last X, yesterday, X ago

neg

Relative Time:

Quantification:

before X, after X

ever, never

Duration:

Frequency:

since, for

once

present

Relative Tense:

anterior

Phasal Polarity:

pos (already)

negpos (not yet)

Duration:

Phasal Aspect:

continuous

resultative/perfect

progressive

Its aim is to explicitly make a case for a two-way distinction in FDG when it comes to the uses of the PrP into

the phasal operator ‘Resultative’ and the relative tense operator ‘Anterior’. This is done taking into account

the ‘Principle of Formal Encoding’, in other words the FDG community’s commitment to only include those

semantic and pragmatic distinctions in the model that are indeed reflected in the form of the language

analyzed (cf. e.g. Keizer 2015: 15). To that end, each of the readings of the PrP discussed in the previous

section is addressed separately, starting with the resultative reading, followed by the experiential one and

finishing with the perfect of continuous/persistent situation. Special attention is again given to the different

readings of the PrP and the presence, absence and kind of adverbial modification.

3.1 Perfect of Result

Most straightforward to describe, since it directly corresponds to the phasal operator, is the Perfect of

Result. According to Schlüter (2002: 181), about 67% of the individual SoAs in PrP constructions that are not

Perfects of Continuous/Persistent Situation, appear to explicitly encode resultativeness in the classic sense

of the Resultative operator focusing on the inherent result of a SoA. Most naturally, this can be seen with

Accomplishments and Changes, where the inherent conclusion of a telic situation is brought to the fore. A

sentence like She has died her hair or She has torn up the manuscript have such clear results that these are

easily recognized and foregrounded. So, within the entire situation that is described by the sentence, from,

to take the first one, the woman applying die, washing it out, drying her hair, and eventually sporting a new

hair color, it is the last step that is of interest. The phenomenon is not limited to telic situations with such

clearly inherent results, however. In (3) we can see that there must be evidence for the atelic, uncontrolled,

dynamic SoA progress, as can be seen from the use of obviously.

(3)

Obviously her condition has progressed much faster than anyone expected. Unfortunately, one of the

worst things has happened. The paralysis has affected her breathing muscles. (COCA, MAG)

This evidence is further specified in the subsequent sentence. In atelic SoAs, the Resultative operator must

therefore be able to affect more than just the steps that explicitly structure a SoA internally. It can not only

zoom in on and foreground a step within the SoA but must also be able to bring to the discourse such results

of the SoA as are only implicit. In fact, this is what seems to be the case for Experiential Perfects once their

larger context is considered.

�614

J. Skala

3.2 Experiential Perfect

From a functional point of view, the experiential PrP is rather opaque. Comrie (1976: 58), focusing on the

form’s semantics, states that an experiential Perfect “indicates that a given situation has held at least once

during some time in the past leading up to the present”. This is certainly true for (4), but equally holds for

(5) as well, where the Past Simple is used instead of the PrP.

(4)

Yet even though China’s leaders struggle to rationalize a conflicted policy, it would be wrong to conclude

that yuan internationalization is doomed. After all, China has managed such contradictions successfully

before. (COCA, academic)

(5)

In 1971, McDowell and Richard and Mary Woodward started the Woodward and McDowell political

consulting firm in Burlingame. They managed many of the state’s best-known campaigns, including

defeat of a pay limits proposition, creation of the California lottery, election of Sen. S.I. Hayakawa and

the re-election of Gov. Ronald Reagan. (COCA, news)

It is, therefore, difficult to say what functionality an experiential PrP in that sense might have, i.e. what it

is that triggers the morphosyntactic form PrP. The example sentences used to illustrate this reading, like

the one in (6) typically involve frequency modification, which is located at the layer of the Configurational

Property.

(6) Harry has visited twice this week (Michaelis 1998: 115; my emphasis)5

This would suggest that the corresponding operator should also be found there as well. Looking at the

co-text of such uses of the PrP in the COCA supports this notion. Clauses that include the PrP as well as a

frequency modifier tend to follow a pattern similar to the one in (7).

(7) Toms has won twice this year and would be a prime Player of the Year candidate with a victory this week

at Oak Hill. (COCA, news)

While it is not the final step within the SoA that is foregrounded and marked as relevant for the addressee,

the fact that this particular SoA has come to pass twice is important for the interaction. The two previous

winnings set the player named Tom up for the Player of the Year award. The connection in Existential

Readings might not be quite as strong as in those typically classified as Resultative. In (3) in the previous

section, the direct result of the SoA, the paralyzed breathing muscles, was relevant for the situation (in this

case medical interventions). The difference to the examples of Experiential Perfects is minor, though. While

in (4) the SoA that took place at some point in the past might not have had a tangible direct result that can

be highlighted, it is the fact that China has managed to deal with such situations that is foregrounded.

For Comrie (1976) of course, this reading constitutes a subtype of the PrP, subordinate to the overarching

notion of current relevance. The notion of a phasal operator that, as Hengeveld and Mackenzie (2008: 210)

put it, “indicate[s] the relation between the temporal reference point and a phase within the development

of a State-of-Affairs” can be applied in a somewhat similar way as with resultative readings; the result

that is relevant at the temporal reference point is not the direct result of the SoA but the result of the past

existence of the SoA itself and the implications thereof. With prototypical examples, this distinction is

small, and no difference in the syntactic behavior of these two reading can be detected. Therefore, at this

point, employing the phasal operator ‘Resultative’ for this group of PrP sentences is the logical choice and

true to the Principle of Formal Encoding.

5 Michaelis (1998), as well as others call this reading “Existential” rather than ‘Experiential’. Following Werner (2014: 72), this

is seen as a difference in terminology rather than in reference.

�The Present Perfect Puzzle in US-American English: an FDG Analysis

615

3.3 Perfect of Continuous/Persistent Situation

According to Schlüter (2002: 197), about half of the PrP constructions of persistence in US American English

contain non-dynamic SoAs. This, in and of itself, is noteworthy. If a speaker wants to code that a nondynamic SoA persists at speech time, it would be sufficient to use the present simple. If one considers,

for example, sentences (8a) and (8b), it is (8a) that invites a continuous interpretation; (8b) is, at best,

ambivalent regarding a state persisting at speech time (cf. also Nishiyama and Koenig 2006: 267).

(8) a. His family lives in North Carolina

b. His family has lived in North Carolina.

c. His family has lived in North Carolina for eight generations, as has Aiken for most of his life. (COCA,

magazine)

What makes a persistence reading likely is a modification of such a combination by a temporal adverbial

indicating duration, as can be seen in (8c). According to Schlüter, about two thirds of the PrPs with a

non-dynamic SoA that he classified as continuative are modified by an adverbial of time (Schlüter 2002:

254).6 Neither the non-dynamic SoA nor the modification by a temporal adverbial indicating duration is a

guarantee for a Perfect of Persistent Situation however. If one considers the context in (9), one can clearly

see that Garcia no longer lives in another part of Atlanta, but has moved back to the neighborhood where

she used to live, namely the one which resembles a small Mexican pueblo. The time living elsewhere has

changed her; she now perceives the men living in her old neighborhood as “hard headed”, so the result is

still present, but her time in a part of Atlanta other than her current place of residence is clearly over.

(9) A Mexican market opened three years ago, called ‘The San Marca’, to serve them. Garcia came to the

United States when she was 11, lived in the neighborhood, went to high school in Atlanta and now speaks

perfect English. She has lived in other parts of Atlanta for several years and is a few steps removed from the

ways of a small Mexican pueblo. She complains that the men living in the apartments are “hard-headed.”

“You won’t make them change their minds,” Garcia said. (COCA, newspaper)

It might, therefore, be more accurate to talk about a durational reading. This duration, however, is not

brought to the sentence by the PrP but by the durational modifier for several years, or possibly in part by the

non-dynamic nature of the SoA. Unfortunately, Schlüter does not provide an example for the 50 sentences he

has found that show predications including a non-dynamic SoA without a durational modifier, something

that is borne out by the data of the present study as well.

The few examples from the small control corpus of prototypical PrPs compiled for the present paper fall

into two groups, those of restrictive relative clauses, many of which in fact also get their durational element

from co-textual elements such as the years of deprivation in (10)7 and those like (11) that, in essence, could be

classified as resultatives if one takes into account the co-textual elements surrounding the SoA in question.

(10) Cuba’s fate will be decided by those who have stayed in Cuba and suffered years of deprivation, hunger,

abuse, imprisonment and humiliation at Castro’s hands. (COCA, newspaper)

(11) Becoming Spanish of Basque origins is exactly what the Basques in Spain have been resisting for

generations. They are not immigrants, they have stayed home, why should they not on their own ground be

a nation as well as a culture? (COCA, academic)

6 Schlüter does not exclude dtAdvs from his study, so the percentages provided here do include both those adverbial specifications that one would typically expect in combination with the PrP, like, for example, for two years or since 1999, and those that

specify a point or stretch of time in the past, like two years ago, or in 1999. In general, however, it can be said that, for the most

part, it is the expected temporal adverbials he refers to. Only 3% of the temporal adverbial specifications he found are classified

as anchoring a situation in time at a point before the point of speech (Schlüter 2002: 236). This small fraction has little bearing

on the numbers he provides.

7 Many thanks to the anonymous reviewer who has pointed this out.

�616

J. Skala

The same holds for those PrPs with a Continuous reading that include a dynamic SoA and do not fall into

the 70% that are accompanied by a durational modifier found by Schlüter (2002: 253). They do occur, as

can be seen in example (12). The talk show Larry King Live is still running at speech time. Elizabeth Smart

is, presumably, still doing great in Larry King’s eyes.

(12) KING:

ED-SMART:

KING:

ED-SMART:

And, Ed, did you have any qualms about asking Elizabeth to come on here tonight?

You know, Elizabeth doesn’t like to deal with the media and ...

She’s done great.

She has. She is wonderful and I am so proud of her. (COCA, spoken)

However, persistence does not seem to be the main point. A resultative interpretation, where Elizabeth’s

apparent ease in the situation justifies that it was okay to ask her to be in a radio show seems more likely. If

the speakers wanted to put emphasis on the fact that Elizabeth indeed continues to do great at that point,

opting for the Present Progressive might suggest itself as the more natural choice. She is doing great would

make clear that it is ongoingness that is encoded, and so would She has been doing great. Indeed, Schlüter’s

analysis shows that in about a third of the continuative readings with a dynamic SoA, a progressive form

is used (Schlüter 2002: 197), suggesting that ongoingness is encoded via the phasal operator ‘Progressive’.

It follows, then, that, while a large number of sentences in the PrP indeed refer to a situation that

holds at speech time, this does not seem to be what triggers the combination of the auxiliary have and a

past participle on the Morphosyntactic Level. Durational modifiers or the phasal operator ‘Progressive’ are

largely responsible in formulating and encoding the notion of persistence. There is, however, a result that

becomes available for the discourse situation. This result is not marked in any other way. The PrP form of

‘do great’, is an atelic action, which does not, as such have a direct result that can be foregrounded in the

prototypical manner of a phasal aspect, nevertheless stresses that there indeed is a result of this ‘doing

great’. So, even in these cases the most straight-forward analysis is that the PrP is triggered by the operator

‘Resultative’.

3.4 Summary of the classical readings in FDG

At the lowest layers on the RL we have seen that, in the majority of cases, the notion of continuity associated

with the PrP appears to be encoded not via the PrP but through durational adverbials triggered by duration

modifiers or by the phasal operator ‘Progressive’, expressed by ‘be + V-ing.’ The phasal operator ‘Resultative’

on the other hand does appear to reliably trigger the PrP construction and can be said to account for the

instances of the reading called the Perfect of Result in that the final step in telic SoAs and the immediate result

of atelic ones is foregrounded. A similar analysis holds for the Experiential PrP as well. The following section

moves up one layer, addressing the role of a PrP form if the SoA in question forms part of a larger Episode.

3.5 Relative tense

So far, the morphosyntactic form auxiliary have + past participle has been considered in terms of its

representation at the layer of the SoA and the Configurational Property. Returning to the notion of the

PrP as signaling that a SoA has taken place in the ‘pre-present zone’ discussed in Section 2, as well as to

Hengeveld and Mackenzie’s (2008: 417) analysis of they have heard the news already as being triggered by

a combination of the two operators relative tense ‘Anterior’ and absolute tense ‘Present’, this section now

looks at the next-higher layer, that of the Episode. It will be argued that the notion of a SoA-organizing

relative tense operator ‘Anterior’ does apply to the English PrP independent of the operator ‘Resultative’

discussed so far, so, pace Connolly (2015) a difference between these two operators needs to be made.

Hengeveld and Mackenzie (2008: 157) define an Episode as “one or more States-of-Affairs that

are thematically coherent, in the sense that they show unity or continuity of Time (t), Location (l), and

�The Present Perfect Puzzle in US-American English: an FDG Analysis

617

Individuals (x)”. At this layer, the absolute temporal location of all SoAs that fall within this Episode is

determined; therefore both operators and modifiers specifying absolute time have scope over all the SoAs

within the Episode.

Presumably, the Episode containing the PrP must have a Present Tense operator. Only this can trigger

the Present Tense inflection of the auxiliary verb have in English. If this Episode contains more than one

SoA, and there is one that took place at an earlier point than the other(s), then it is the operator ‘Anterior’

that triggers have + past participle on the Morphosyntactic Level. In this case, the PrP can be seen as

analogous to the English Past Perfect, as illustrated in (13) and (14).

(13) After she has laid the receiver in its cradle, Dedi goes on elaborating the root system of her anacahuita tree,

shading the branches, and then for the fun of it, opening and closing the flap of the envelope. (COCA, fiction)

(14) After she had thought for a moment, and after she had given up trying to release her hand from his grasp,

Yvonne began to walk, half ‘before him’ and half ‘behind him’. (COCA, fiction)

(13) is clearly different from the examples discussed in previous sections. There is a relative temporal

relationship between the SoA in PrP and the other SoAs, but no result of the act of ‘laying the receiver in its

cradle’ is foregrounded. While in the example sentences in previous sections, SoAs did not typically show a

unity of Time or Location with any other SoA, here this necessarily is the case. The PrP here must be presented

together with SoAs in Present Tense that are part of the same Episode, and are typically modified by relative

tense modifiers, since it serves a different function here, that of establishing the sequence of events.

4 An analysis of Present Perfect sentences with time-specifying

adverbials

If one takes into account the discussion in the previous section, the restriction on the combinability of the

PrP with dtAdv (the “Present Perfect Puzzle”) does not come as a surprise. The PrP can be triggered by the

Anterior operator. Then the SoA, while anterior to some other SoA, falls within the time-span of the Episode,

which takes place in the present. This allows for modifiers of relative, but not absolute time. The other

operator that triggers the PrP, the phasal operator ‘Resultative’, foregrounds results and consequences that

hold at the moment of speech. If these are emphasized, then temporal specification of the situation that has

brought them about does not suggest itself (cf. e.g. Mittwoch 2014: 228-229). Instead, modifiers at the layer

of the Configurational Property can be expected.

Understandably, then, the use of time-specific adverbials in combination with the PrP occur so rarely

that several linguists perceive it as a constraint on the use of the PrP (e.g. Dahl 1985; Klein 1992; Portner

2003; Elsness 2009, to name but a few). At the same time, researchers conducting large-scale corpus studies

on the PrP (e.g. Schlüter 2002; Hundt and Smith 2009) do find these co-occurrences with a frequency and

consistency that has led quite a number of researchers (e.g. Harder 1997: 417; Rastall 1999: 81; Miller 2004:

235) to state explicitly that they consider these combinations felicitous, and to propose analyses of these

co-occurrences.

One’s first interpretation of such a co-occurrence of dtAdvs and the PrP might be that the PrP in

US-American English follows the development the form has taken in other languages, such as German

and Dutch, and is developing into a periphrastic form signaling full past tense. Indeed, many authors (e.g.

Rothstein 2008; Walker 2017; Werner 2017) have remarked upon the typological oddity English represents

in this respect. That English should now succumb to this ‘aoristic drift’, to use Squartini and Bertinetto’s

(2000: 404) term, would not come as a surprise. Investigations such as Walker’s (2017) into the Old Baily

Corpus point towards such a development, at least to the respect that the narrative uses of the PrP he has

investigated in this study do not appear to occur sufficiently frequent in the Old Baily Corpus.

At the same time, his earlier work (Walker 2011) indicates the opposite to be true. Looking at the genre

restrictions and the regional distribution of the form, Walker tentatively concluded at that time that what

�618

J. Skala

we might be “witnessing is a much older state of affairs which is only now coming to light“ (Walker 2011:

83). That we find narrative uses of the PrP even in the lyrics of folk songs from the 1800s (Walker 2017:

29–30) rather gives weight to his previous interpretation of the phenomenon. In light of this, but especially

because in US-American English the PrP is not increasing in proportion to the Past Simple (cf. e.g. Hundt

and Smith 2009; Yao 2015: 255), the notion that what we are witnessing is a general shift along the aspect

cycle is rejected pending further evidence.

Alternative proposals, like, for example, that by Miller (2004: 235) suggest that “[w]hen speakers refer

to an event in the past they are under pragmatic pressure to enable listeners to locate the event accurately

in past time. This is achieved by producing an appropriate adverb referring to a specific past time”. Werner

(2017: 78) supports this view, describing it as one possible interpretation presenting itself in light of the

data.

Taking into account that, as Giomi puts it, a “basic assumption of functional linguistics is that a

language is first and foremost a social tool and, as such, is shaped in the first place by the ever-changing

communicative needs and strategies that arise among the community of its speakers” (Giomi 2017: 40), a

functional theory must then also be able to account for speakers’ responses to such pragmatic pressure,

especially if these license new forms within a given language. FDG can, indeed do that by virtue of its

integration of the context a given utterance is used in into the model. Using Heine’s (2002) description of

context-induced reinterpretation, Giomi has outlined how FDG can successfully model different stages of

grammaticalization, from bridging contexts via what Heine (2002: 83) ”calls the “switch context stage” to

conventionalization, which is summarized in brief in the following section. He proposes a process in which

the combination of the construction’s meaning and the relevant shared information, which can be “contextsituational, co-textual and/or encyclopedic in nature” (Giomi 2017: 50), is modeled via the interaction

between the Grammatical and the Contextual Component.

4.1 A model of meaning change in FDG

According to Giomi “grammaticalization is triggered by the conventionalization (or ‘semanticization’)

of a pragmatic inference” (Giomi 2017: 46), which he links back to Grice’s (1975: 58) statement “that

conversational implicatures may ‘become conventionalized’”. What happens is that “an alternative, more

contextually relevant meaning is thus foregrounded by means of an inference and the construction is

reinterpreted” (Giomi 2017: 51).

At this point, though, the underlying representation is still that of the source meaning, while in the

Contextual Component, as Giomi proposes, it is the new meaning “that represents the actual contribution

of the construction to the shared common ground” (Giomi 2017: 51). Encyclopedic, co-textual or, indeed,

contextual information leads to this contextual reinterpretation that is, at that point, not part of the

grammatical component. The reanalysis can have an effect on the representation of the structure in the

Contextual Component. In this first stage of language change, the bridging context, neither the information

on the function, nor the consequent new representation enters the Grammatical Component.

Once an utterance is produced that can only be read in light of the target meaning, this interpretation

and the new underlying representation enter the Grammatical Component (Giomi 2017: 54). In the switch

context stage, however, the new meaning still depends on a certain kind of context for it to be available. As

soon as the form can be used with the new meaning in a context that would usually have favored the source

meaning, explicit influence on the inference process in the Contextual Component is no longer necessary;

the target meaning has conventionalized and has thus become part of the Grammatical Component (Giomi

2017: 63).

The implication of this for the present analysis is, first and foremost, that any change in meaning needs

to be motivated by an implicature that is present in the context a construction is used in. In order to examine

this, 100 randomly selected sample sentences from the COCA (stratified in terms of genre and Aktionsart)

were extracted and analyzed in terms of their similarities to the patterns described in 4.2. Secondly, there

can be different stages of conventionalization for a construction. The fact that the PrP together with dtAdvs

�The Present Perfect Puzzle in US-American English: an FDG Analysis

619

still strikes native speakers as decidedly odd if such a sentence is presented to them in isolation suggests

that this combination has not conventionalized; after all, it cannot (yet) be used context-independently.

On the other hand, it is produced by native speakers in certain contexts, and the very fact that a dtAdv

is present excludes a reading of the form as phasal with the final phase that is foregrounded holding at

speech time, so a case is made in the following sections that the PrP together with dtAdvs may represent a

switch context stage for the PrP, where the Contextual Component still plays a large role in the successful

interpretation of the utterance.

4.2 The Dataset

For the present study, a data set of 497 co-occurrences of the PrP and a dtAdv in the COCA was compiled by

automatically isolating all the declarative sentences that include the finite auxiliary verb have followed by a

past participle no more than four words away, using the BYU search interface. In the interest of eliminating

overlapping influences, instances of the Present Perfect Progressive were excluded automatically. The

resultant list was then further reduced to those examples that included one of the following dtAdv typically

said to not combine with the PrP ago / yesterday / last+part-of-year / before+event-in-the-past / in+cardinal

number / as far back as+cardinal number (cf. e.g. McCoard 1978: 135; Declerck 2006: 593), no further than

eight words away from the past participle. 500 random integers were generated using the random number

generator function in R (R Core Team 2015), corresponding to example sentence numbers in the list. These

examples were manually sorted through, in order to ensure that the PrP and the dtAdv were indeed part of

the same clause. Examples by non-native speakers or deliberately distorted texts (like the fictional variety

of English produced by an alien species), as far as this could be determined from the example sentence

itself, were excluded this way as well. For each example sentence that did not meet these criteria, a new

random number was generated. The aim was not to draw an exhaustive sample of dtAdv+PrP-constructions

from the COCA, but to find a sufficient number of them to be able to describe possible patterns they occur

in. Therefore, only a small number of Advs prototypically associated with the Past Simple has been used

in the search. Three example sentences were only found to be unsuitable at a later stage, resulting in

the somewhat unusual number of 497 total example sentences. Table 2 provides an overview of the text

passages that make up the data base.

Table 2. Overview of database of non-prototypical Present Perfect constructions isolated from the COCA

dtAdv

Examples

absolute dtAdvs

calendaric dtAdvs

relative Advs + specification

total

total

spoken

written

news

yesterday

318

231

57

30

in 1998

99

14

57

28

before dinner

80

29

35

16

497

274

149

74

What can be seen here is that, clearly, the combinations of the PrP and dtAdvs occur most frequently

in spoken discourse, especially if one takes into account that the genre “News” is also, at least in part,

characterized by spoken utterances. This is unsurprising, as this is where one would expect a form that

prescriptively is certainly discouraged. The same can be said, if this should eventually be identified as a first

instance of language change. It is, however, also obvious that this combination of PrP and dtAdv is not only

a characteristic of spoken language. Texts from all genres include these combinations, as well as a number

of academic texts.

What should not be inferred from Table 2 is that absolute dtAdvs are far more common in such a setting

than calendaric or other kinds of dtAdvs. The difference in frequency between the adverbial types must

largely be ascribed to the nature of the search parameters the COCA interface permits. Since for all dtAdvs

except for yesterday and ago sets of NPs (like last + Monday/Tuesday/week/…) had to be entered to find

the relevant instances, many other instances of such a specification will not have been found. Since the

�620

J. Skala

aim was to arrive at a set that was large enough to be analyzed in terms of grammatical patterns rather

than an exhaustive list that would permit a quantitative analysis, this limitation was deemed acceptable.

Consequently, however, no quantitative claims will be made in this paper.

In addition to this data set, a second set of sentences was extracted from the COCA, consisting of 100

uses of the PrP, balanced in Aktionsart and genre, that are not modified by a dtAdv. This set served as

source for conversational implicatures that might be open to entering the process of grammaticalization.

Two patterns that have emerged in both sets will be described in the following section.

4.3 Data description

Before relating two of the most prominent patterns in the PrP + dtAdv data set to the conversational

implicatures found in examples from the second data set, the two patterns are here described in isolation.

4.3.1 Reference identification pattern

One grouping made within the data set again underlines the notion of a relevant result, but this result is

relevant in a different manner, namely when it comes to accurately identifying a referent. These come to a

large extent in the form of restrictive relative clauses, like in (15).

(15) With Iran’s refineries uninterested in producing gasoline for such meager prices, the Iranian government

is now forced to rely on imports. Those importers who have already built up their supply lines in 2006 are

now the only companies that still look at comparatively stable revenue. (COCA, academic)

It is only those importers who now have supply lines built up – because they did built them up early,

already in 2006 – that are selected as referents in this sentence. Again, both the current result and the point

in time at which this result was brought about are relevant for the discourse, in this case for a successful

identification of the intended referent set.

4.3.2 Justification pattern

More than half of the data examined are paragraphs in which the SoA in the PrP justifies another part of

the discourse. What exactly is justified, however, differs between the examples. In (16), for example, the

speaker’s action of uttering an apologetic formula is justified by the following discourse act, as if in answer

to the question why the speaker is making this apologetic statement.

(16) I have some very bad news for you, sir. I’m terrible sorry to have to tell you this, but Monsieur Kane has

passed away almost two weeks ago. (COCA, fiction)

That the actual production of a Discourse Act is justified is comparatively rare, though. A more common

pattern among the set of examples classified as Justifications is that where the speaker justifies his or her

opinion regarding the truth of a statement via such a Discourse Act. (17) is an example of this group.

(17) Newly elected Senate President Bill Rodmorow, a Colorado Springs Republican who was very influential

during the 2013 gun control debate, said it is much too early to tell how the session will turn out. But he

is optimistic that he can at least keep the peace during the session, as he is a man who has successfully

played the role of mediator in November 2008 during the elections and feels this is not much different.

“Also, I have five children,” he adds with a grin. (COCA, newspaper)

�The Present Perfect Puzzle in US-American English: an FDG Analysis

621

It is a specific event in the past that serves as Justification for the Senate President’s optimism regarding

his ability to keep the peace. This instance is used as evidence, as it were.

The dataset includes quite a number of examples that, as Hannay and Keizer (2005: 174) put it, function

to “explain why the state of affairs expressed in the matrix prediction holds”. This type of Justification

(Just8) is illustrated in (18). Because the male figure in this text has already left, the second cup of coffee is

for the French secretary.

(18) “C’est pour Monsieur?” Nanon said, glancing at the second cup.” Oh,’’ said Madame Fortier. “He has gone

to the terraces, long ago. The second coffee is yours, my dear.” (COCA, fiction)

This connection between the two Discourse Acts is not made explicit, except through the PrP, which

indicates that it is the result of Monsieur’s leaving that is important, and that from this an inference can be

made. This inference takes the form of the second Discourse Act.

There are also a number of example sentences that justify a speaker’s assertion that a certain entity is

assigned a property by the speaker, as can be seen in (19).

(19) It’s a great program. We have expanded Medicaid here twenty years ago. And for twenty years every child

in Vermont has been eligible for health insurance. (COCA, spoken)

In this context, the speaker assign the program the property of being great. In order to justify the claim, the

speaker needs to emphasize the relevance of the expansion at speech time as well as provide a description

of the situation forming the basis of their claim (including a specification of when it happened). Had they

only expanded Medicaid recently, the program could probably not have had a major effect yet.

While these example sentences might seem very different at first glance, each of them has a co-textual

element that is clearly justified by the SoA in PrP, a similarity that is illustrated in Figure 1.

SoA in PrP

Result

SoA in PrP

He is not here.

Speaker’s action of uttering

an apologetic formula

(17) Bill Rodmorow has

successfully played the

role of mediator.

He has experience

regarding this

kind of work.

He believes that he will be

good at keeping the peace.

(18) Monsieur has left.

He is not here

to drink coffee.

(19) We have expanded

Medicaid here

twenty years ago.

It has been available

for a while now.

(16) Monsieur Kane

has passed away.

This cup of coffee

is for Nanon.

The program is great.

Figure 1. Parallels between examples of different Justifications

8 In their 2005 paper, Hannay and Keizer use the symbol ‘Rel’ for this operator. Since, in the context of the PrP, this might be

misleading, suggesting terms like ‘relevance’ or ‘relative’, ‘Just’ is suggested here instead. In the following, it will be used to

indicate where the PrP appears to be used because the speaker wishes to mark that an Episode that took place in the past is used

to justify a piece of discourse at speech time.

�622

J. Skala

4.4 Data Analysis and Discussion

An analysis of what characterizes the groups laid out in Section 4.3 must be true to two commitments: it

has to account for the similarities in function the patterns show, and it has to resolve the clash of having

both an absolute time operator ‘Present’ triggering the Present Tense form of ‘have’, and an absolute time

modifier that signals pastness. At the same time an adequate analysis also needs to be in line with the

patterns of language change observed in other languages, and adhere to the principles a change in meaning

is generally assumed to follow. One such principle there appears to be a consensus on is that if there is

grammaticalization, this tends to come in the form of a scope-widening process, so, a move upward in

layers or levels (cf. e.g. Gelderen 2011; Hengeveld 2011). Giomi (2017) shows that such scope-widening can

adequately be sketched using FDG.

4.4.1 Reference identification

The parallels between the group classified as reference identifications and a conversational implicature

in prototypical PrP examples is not difficult to pinpoint, especially since the pragmatic motivation behind

such a use is fairly clear. In sentences like (15a), reproduced from Section 4.3.1, two things happen at the

same time.

(15) a. With Iran’s refineries uninterested in producing gasoline for such meager prices, the Iranian government

is now forced to rely on imports. Those importers who have already built up their supply lines in 2006

are now the only companies that still look at comparatively stable revenue. (COCA, academic)

There is a clear result of the action in the past. The companies look at comparatively stable revenue. This

result, however, could only have come to pass because of the point in time at which the action was taken. If

a temporal specification is necessary for this result – like in this case, where different regulations apply to

those companies who might have supply lines but built them up later – then it can be provided.

A more accessible example might be provided by the two different readings of the same sentence in (20).

(20) a. I have run around the stadium twice. I know what it looks like.

b. I have run around the stadium twice. Now the race is done and I can go home.

In (20a) the frequency modifier twice might strengthen the immediate result of having run around the

stadium, but the result need not depend on this modification. In (24b) the result is only there if the stadium

has been circled twice, it is thus intrinsically necessary for the correct resultative reading that the modifier is

present. If twice were to be left out, the Episode would not constitute grounds for the unit that follows. Only

the result of the two laps has a resultative link to the race being done. This kind of very specific situation

appears to be open for an analogy that includes a dtAdv, serving as a bridging context for a construction

where modification takes place at a higher layer. The reanalysis that must take place in such a situation is

that there is a result that is available in the discourse, but that this result does not come solely from the final

phase of a SoA, but also from additional modification thereof.

A representation for such a sentence, representing a switch context stage, would therefore not include

a Resultative operator (res) at the layer of the Configurational Property. After all, such an operator would

not have scope over the temporal adverbial at the layer of the Episode that is crucial for the distinction

between the possible results that have an effect on the Individual. This is the kind of relationship between

the Episode, the result and the ascription that has been demonstrated in (15). The dtAdv in 2006 cannot be

left out if one is to arrive at the group of importers the speaker is referring to.

The function of the relative clause is to modify the individual, as illustrated in (15c)

�The Present Perfect Puzzle in US-American English: an FDG Analysis

623

(15) b. those importers who have already built up their supply lines in 2006

c. (m dist xi: [(fi: importerN (fi)) (xi)φ]: (res epi: (negpos ei: [(fci: [(fj: build-upV (fj)) (xi)A (m xj: (fk: supply

linesN: (fk)): (xi)Ass (xj))U] (fci)) (ei)φ]) (epi): (ti: ‒ in 2006 ‒ (ti)) (epi)))

That the PrP has such an effect on the individual is, for example, illustrated by Dik (1989: 190), who explains

the semantic interpretation of John has cried as John having a certain set of properties now that permit

the conclusion that at a specific point in time previously John cried. In (15), the Episode modifying the

Individual x1 in such a way is in turn modified: the absolute point in time at which it took place is provided.

Since this is a modifier that cannot interact with a present operator, no such operator of absolute tense is

included in the representation of ep1. Instead, the Resultative operator at the layer of the episode triggers

the form have + past participle for the entire episode, which can be modified in terms of the time it took

place.

4.4.2 Justifications

In the small sample of PrP uses without dtAdv modification, a surprisingly large number could be classified

as a Justification of one kind or another. For instance, returning to example (4), (reproduced here for

convenience) one could say that the speaker justifies her claim that it would be wrong to conclude that

yuan internationalization is doomed by making explicit that China has previously dealt successfully with

similar situations.

(4)

Yet even though China’s leaders struggle to rationalize a conflicted policy, it would be wrong to conclude

that yuan internationalization is doomed (nuclear Discourse Act). After all, China has managed such

contradictions successfully before (justification Discourse Act). (COCA, academic)

(4) can therefore feasibly be classified as a Propositional Justification.

Such an analysis on the Interpersonal Level would also shed light on what triggers the PrP in some

of those example sentences that are typically classified as Perfect of Persistent Situation. In example (11)

(again reproduced) a similar relationship holds.

(11) Becoming Spanish of Basque origins is exactly what the Basques in Spain have been resisting for

generations. They are not immigrants (nuclear Discourse Act), they have stayed home (justification

Discourse Act), why should they not on their own ground be a nation as well as a culture? (COCA,

academic)

Here the speaker makes a case for a difference between Basques and immigrants. People who have moved

to Spain from France would be Spanish of French origin. People who originally came from Egypt would be

Spanish of Arabic origin. The Basques have not moved to Spain, they have been there for centuries. The

ascription of the feature not immigrants to they is justified by the Discourse Act stating that they have stayed

home (rather than moved there).

In the example set (21), (21a) also illustrates such a continuative reading. When it says that his lions will

be dependent on him for the rest of their lives. They have all known him since they were a few months old it

does not seem to be the continuous knowing that triggers the PrP. Other alternative events occurring wholly

in the past, like the imagined continuation They have gotten used to being fed would be expected to trigger

the PrP as well, if their purpose is to support and justify the previous discourse act. Similarly, one can argue

that in (21b) the low number of high school graduates justifies the Discourse Act The shift will not be as

simple as filing resumes and answering want ads and that in (21c) Roberta’s moment of learning supports

her choice to say Please, doctor.

�624

J. Skala

(21) a. He says that if cub petting and canned hunting were stopped immediately, he would give up all of his

lions. He means this as a way to illustrate his commitment to abolishing the practices rather than it

being an actual possibility […] [I]n reality his lions will be dependent on him for the rest of their lives

(nuclear Discourse Act). They have all known him since they were a few months old (justification

Discourse Act). But now most of them are middle-aged or elderly. (COCA, magazine)

b. The shift will not be as simple as filing resumes and answering want ads (nuclear Discourse Act).

Ninety-four percent of Colorado’s adult AFDC recipients are women, and 80 percent of recipients are

single parents. Only about half the recipients have finished high school (justification Discourse Act).

The average welfare parent has two children, and statewide, 39 percent of those kids are under age 5.

(COCA, newspaper)

c. Dr. Zhang drops Roberta’s folder into a wire basket […] and calls through the intercom for her next

patient. Then she sneezes again. “Please, doctor (nuclear Discourse Act),” says Roberta. She has

learned long ago that addressing all health professionals as ‘doctor’ – even dental hygienists – makes

them feel important and thus generous (justification Discourse Act). “I’m not here on a prank.”

(COCA, academic [fictional])

Even Schlüter’s (2002: 198) proposal of a PrP of persistent situation, can be analyzed along these lines:

(22) We’ve all been rich and spoiled long enough Just to hate the machine age (nuclear Discourse Act). (BrownUniversity Corpus)

The adverbial long enough can be seen as constituting a part of the SoA, and it is the entire predication

that serves as Justification for the propositional content of the dependent clause. All of these PrPs could, in

theory, have been triggered by a frame like (23):

(23) IL: (M1: [(A1)Just (A2)](M1))

This connection is so common a pattern that Nishiyama and Koenig (2006: 273) list it as one of their three

default inference patterns of the PrP:

Authors sometimes use the perfect to indicate that the occurrence of an event provides evidence or an explanation for the

truth of a claim she made or will make. The value of X in these cases is the state description conveyed by a clause that

preceded or followed the sentence containing the perfect.

In their work on appositions, Hannay and Keizer (2005) describe six different types of Justifications, almost

all of which can be found frequently in the database of constructions that include the PrP and dtAdvs

compiled for this study. Examples (16–19) from Section 4.3.2 illustrate four of these types.

Speech Act Justifications, i.e. Discourse Acts whose function it is to serve as Justification for another

Discourse Act (cf. Hannay and Keizer 2005: 174), are what we find in example (16).

(16) I have some very bad news for you, sir. I’m terrible sorry to have to tell you this, but Monsieur Kane has

passed away almost two weeks ago. (COCA, fiction)

A Discourse Act, to use Hannay and Keizer’s (2005: 174) words, can also “explain why the speaker thinks

something to be true, false, probable, etc., or […] adduce evidence for the truth of the statement conveyed

in the matrix sentence”. (17) is an example of this group.

(17) Newly elected Senate President Bill Rodmorow, a Colorado Springs Republican who was very influential

during the 2013 gun control debate, said it is much too early to tell how the session will turn out. But he

is optimistic that he can at least keep the peace during the session, as he is a man who has successfully

played the role of mediator in November 2008 during the elections and feels this is not much different.

“Also, I have five children,” he adds with a grin. (COCA, newspaper)

It seems not unlikely that with the conceptualization of this previous action as evidence for the

�The Present Perfect Puzzle in US-American English: an FDG Analysis

625

proposition in the nuclear Discourse Act, concrete information about and identifiability of this action is

desired. That after all could be inserted into the Discourse Act that contains the temporally specified PrP,

including the slot between the auxiliary and the past participle, supports the notion of this being used as a

Justification (cf. Hannay and Keizer 2005: 174).

Considering the strong resultative function the PrP seems to express, it comes as no surprise that the

dataset includes quite a number of examples that, as Hannay and Keizer (2005: 174) put it, function to

“explain why the state of affairs expressed in the matrix prediction holds”. This type of Justification, which

they call SoA motivation, (Hannay and Keizer 2005: 174) is illustrated in (18):

(18) “C’est pour Monsieur?” Nanon said, glancing at the second cup. ”Oh,” said Madame Fortier. “He has gone

to the terraces, long ago. The second coffee is yours, my dear.” (COCA, fiction)

(19) then is an example of a Property Justification. Again, this seems a logical fit for a situation in which

a speaker might choose to employ both the PrP and a modifier that specifies the absolute point in time at

which something has taken place.

(19) It’s a great program. We have expanded Medicaid here twenty years ago. And for twenty years every child

in Vermont has been eligible for health insurance (COCA, spoken)

It stands to reason that addressees can indeed infer this connection between two Discourse Acts in

prototypical uses of the PrP and that it is available in the Contextual Component as a pattern that speakers

can make use of. At the same time, though, this inference does not necessarily have to be made. A

straightforward resultative reading is possible as well. Because both, the source and the target meaning are

available here, the example sentences listed in this subsection that do not include a dtAdv may be seen as

bridging contexts, characterized by a certain degree of ambiguity. This is no longer the case once a dtAdv

is present. Since the SoA is anchored in time, we cannot talk of a phasal operator anymore, through which

the PrP is typically understood as being triggered in FDG. Licensed by this co-textual condition, the PrP is

instead used as a different operator, namely as one signaling Justification.

5 Conclusion

The English PrP does not often appear in combination with a dtAdv. At the same time it has to be admitted

that these two forms indeed do co-occur. Evidence for this can be found in a number of studies (e.g. Walker

2008; Ritz 2010) as well as in data from all genres represented in the Corpus of Contemporary American

English. Consequently, this pattern requires a description as well as an implementation into existing

theoretical models.

As basis for such a description serves the assumption that meaning extensions that conventionalize

start out from core meanings of a form that contribute to its typical use in context. These typical uses in

context, then can act as bridging contexts (Heine 2002: 84–85) where pragmatic inferences can lead to a

reanalysis of the form in question. At this point, the form is still ambiguous and can be interpreted as either

the source or the target meaning. As Giomi (2017: 50) points out, this reanalysis at this point is not part of

the Grammatical Component but is located in the Contextual Component. The PrP, as Michaelis (1994: 130)

underlines, “is token ambiguous” and hence by its very nature open to a number of different inferences. It is

therefore unsurprising that many different meanings, senses and readings for the PrP have been proposed

throughout the literature. Since FDG, adhering to the Principle of Formal Encoding, only models such

changes and difference as are reflected in the form of a language, it only recognizes two readings of the PrP,

that of a phasal ‘Resultative’ and that of the relative tense ‘Anterior’.

Once a change in grammatical behavior exists, however, this needs to be accounted for within the

description of a language. The PrP’s co-occurrence with dtAdvs constitutes such a change. Since the

existence of an absolute temporal modifier signaling pastness renders impossible a purely phasal (and

�626

J. Skala

even more so, a Present Tense anterior) reading, it is of interest to see what commonly occurring pragmatic

inference of the PrP is then available instead.

One such commonly occurring pragmatic inference, illustrated in (24), is that of a Justification (cf.

Nishiyama and Koenig 2006: 273).

(24) We eat things which have been in the dirt only hours ago. They’re pure (COCA, fiction)

In (24), on the Interpersonal Level, the Discourse Act They’re pure is justified be the previous Discourse

Act. The vegetables are evaluated by the speaker as being pure, and this evaluation is justified by them

having a certain property, namely that of hav[ing] been in the dirt only hours ago. It has been shown in the

present paper that this function may well trigger the PrP on the Interpersonal Level and thus not clash

with the dtAdv. That this is only possible in certain contextual uses of the PrP makes clear that this is

not a conventionalized function of the PrP. It rather can be seen as an intermediate stage on the cline of

grammaticalization, which Heine (2002: 83) calls the ‘switch context stage’, where the specific combination

with the dtAdv leads to this re-interpretation on the PrP.