The Ghent Altarpiece

A Reassessment of the Original Work and its Meaning

James David Audlin

From the upcoming third edition of The Gospel of John Restored and Translated, to be published in seven

or eight volumes by Editores Volcán Barú. The author is grateful to “Lasting Support, An Interdisciplinary

Research Project to Assess the Structural Condition of the Ghent Altarpiece” which, at its website

(legacy.closertovaneyck.be/#home), kindly allows the use of images in scholarly publications.

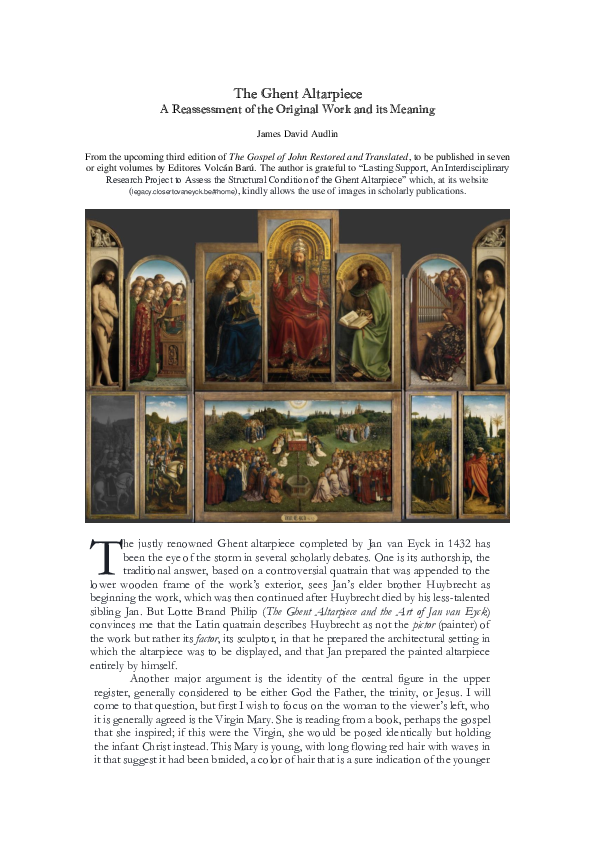

T

he justly renowned Ghent altarpiece completed by Jan van Eyck in 1432 has

been the eye of the storm in several scholarly debates. One is its authorship, the

traditional answer, based on a controversial quatrain that was appended to the

lower wooden frame of the work’s exterior, sees Jan’s elder brother Huybrecht as

beginning the work, which was then continued after Huybrecht died by his less-talented

sibling Jan. But Lotte Brand Philip (The Ghent Altarpiece and the Art of Jan van Eyck)

convinces me that the Latin quatrain describes Huybrecht as not the pictor (painter) of

the work but rather its factor, its sculptor, in that he prepared the architectural setting in

which the altarpiece was to be displayed, and that Jan prepared the painted altarpiece

entirely by himself.

Another major argument is the identity of the central figure in the upper

register, generally considered to be either God the Father, the trinity, or Jesus. I will

come to that question, but first I wish to focus on the woman to the viewer’s left, who

it is generally agreed is the Virgin Mary. She is reading from a book, perhaps the gospel

that she inspired; if this were the Virgin, she would be posed identically but holding

the infant Christ instead. This Mary is young, with long flowing red hair with waves in

it that suggest it had been braided, a color of hair that is a sure indication of the younger

�Mary. On the other hand, she is in the final painting clad almost entirely in blue, both

her outer mantle and the tunic beneath it, and this color of garment most often

associated with Mary the mother.

But note that though her right sleeve is bright red, nothing else shows of

whatever red garment she was wearing. Adding to the oddity, it appears that the mantle

is draped over this sleeve, but the bit of patterned hem cannot be rationally connected

with the rest of the mantle: it is obviously an addition to try to explain the red garment

as under all of the blue. However a look at the underpainting, especially in the blackand-white reflectographic image, makes it clear that the tunic was a very different color

from the mantle, and since the greyscale shade of the tunic is identical to that of the

sleeve it seems a reasonable conclusion that it was red. And whatever color the mantle

was at first, it could not have been the deep rich blue of the final painting, since its

greyscale tone is far too light; I would guess that it was another shade of red. If I am

right, then clothing in these hues would again point to the wife Mary as the identity of

the subject. In addition I note that these vestments constitute a richly ornate bridal

gown, evoking associations with the wedding in Cana and the marriage of the Lamb

and the Bride in the conclusion of the Revelation.

Her head is adorned with a sumptuous crown. The Master of Flemalle, a

contemporary of van Eyck now generally identified as Robert Campin, painted just

such a crown in his Betrothal of the Virgin, displayed in the Prado. A number of artistic

works show the younger Mary in just such a crown as this, though without the flowers

and stars. The design seems quite a lot like one style of Jewish wedding crown, and

that may have been intentional, perhaps imagining the crown that Jesus’s bride wears

in John 2. Indeed the artist could well have seen such bridal crowns during his probable

sojourn in the Holy Land. This crown is adorned with:

First, roses and lilies, calling to mind the only Biblical verse to mention both,

Song 2:1, in which Solomon’s beloved exclaims Ego flos campi et lilium convallium (“I am

the rose of the fields and the lily of the valleys”). There are also columbines, whose

name comes from the Latin word for “dove”, because the flower is thought to

resemble a group of doves; the dove of course also brings Mary the wife to mind,

because of the dove at the immersion. Specifically these columbines are the winecolored aquilegia atrata species, the second word of which refers to someone clothed in

black for mourning. I am certain that these flowers were carefully chosen to give

identity clues to those who knew how to look for them.

Second, twelve precious stones of which seven are visible (both numbers being

sacred), evoking the ( חשןḥšn), the breastplate of the high priest that Mary-and-Jesus

wears when meeting with the disciples after the resurrection and again in Revelation

1:13 (see page Rv1_13t16affD), but most of all of the heavenly city that descends from the

skies/heavens in Revelation 21:1-3 “like a bride adorned for her husband”: note that

this city-bride is said in Revelation 21:18-21 to be surrounded by a wall which has the

same twelve stones in its foundation and pearls for its gates, an account that also

describes this crown. Note too that there are rays painted around her head, as there

are around the two other portraits in this register. Such rays hearken back to Moses

being in the presence of God (Exodus 34:29 and 35; see page ###D for the proper

translation), and indeed God is often described as emitting rays of light Numbers

6:24-26 and several Psalms, including 4:6, 31:16, 67:12, and 80:3), and also Jesus at the

transfiguration (Mark 9:2-8 and cognates) and as he walked through the storm at night

(John 6:19 and cognates), and the resurrected messiah, Jesus-and-Mary, as, together

with God, the lamp of the new Jerusalem (Revelation 21:23b). With such connotations

we must assume that Mary here is being in some way associated with God; I will return

to this matter, but my view is that she and Jesus, in the outer panels in this register,

�unite in the central panel to recreate the

first human being made by Elohim in

Elohim’s image and likeness.

And third, twelve stars whose

irregular configuration is obviously a star

chart. There was not yet a good star chart

available in Europe, the first one being the

1440 Vienna Manuscript (MS 5415), so

either van Eyck records here his own

observations or else he saw an Arabic or

Greek planisphere during his travels in

behalf of Philip the Good. In any case, this

arrangement instantly reminds me of the

lower half of the Corona Berenices, the

cluster of stars that surmounts the head of

Virgo, whose appearance in Revelation

12:1 puts Mary in the glory of the sun as

does van Eyck; this verse is associated with

the resurrection (see page ###), and the

rest of the chapter goes on to recount

much of Mary the wife’s life thereafter.

In an arc of gold over her head this inscription appears:

̅R

̅ SPECIOSIOR SOLE + SVP OE

̅M STELLARV

̅ DISPOSICOE

̅ LVCI OPATA IV

̅ EIT

̅ V PO

HEC E

̅ DOR E

̅E

̅IM LVCIS ETERNE + SPEC̅LM

̅ SN

̅ MACL̅A DI MA[IESTATIS].

CA

She is more beautiful than the sun; + she surpasses all of the constellations of the stars, she is

more radiant than eternal light; + the unblemished mirror of God’s ma[jesty].

Taken from Sirach 7:29 and 26a, these lines describe Wisdom, the wisdom with which

Elohim brought the universe into being in Genesis 1, God’s companion and co-creator

according to Proverbs 8. And Mary, as the Paraclete, sent to remind the disciples of

everything Jesus had taught them, is in effect Jesus’s wisdom, and his companion and

co-creator. The reference to light is reminiscent of how the androgynous first human

was made from the light that Elohim made in Genesis 1:3, and the mirroring of God’s

majesty of course evokes the fact that that individual was made in the image and

likeness of Elohim.

In addition, if this figure is indeed the older Mary, then it is for the second time

that she appears – since when the wings of this gigantic altarpiece are closed upon its

interior another set of portraits appears, one of which is without doubt the mother,

since she is shown in the moment that the angel Gabriel is announcing to her that she

is pregnant with Jesus (Luke 1:26-38). Though the two figures have the same long

wavy red hair and more or less the same facial features (evidently the same model

served for both), the artist has given the exterior Mary green eyes and brows in high

thin curves, unlike the interior Mary’s brown eyes and lower and more pronounced

brows; she also appears plumper with a more pronounced chin, and is pronouncedly

stoop-shouldered, all quite unlike the broad-shouldered interior Mary; and she is

wearing a simple tiara and a virgin’s white cape rather than the ornate crown and

elegant wedding gown of the interior Mary. While the same model probably posed for

both, the artist has evidently taken pains to portray differently two women who happen

to have the same name, Mary.

These clues are intensified in a slightly later painting by Jan van Eyck of the

annunciation to Mary, from between 1434 and 1436, thought to be part of another

�triptych altarpiece the rest of which has been since lost. Jesus’s prospective mother is

rather plain-looking, with a long face wearing an unsmiling expression, and dressed

entirely in the traditional blue. On the other hand, Gabriel is dressed in exquisitely

rendered brocades and rainbow-hued wings, with a bright smile illuminating a very

pretty face. Art historians say it was traditional to make the mother rather plain in

appearance to avoid making her sexually attractive to the viewer, but Gabriel, they add,

being a sexless angel, did not require such treatment. Still, there is no question that this

Gabriel not only is beautiful but seems to be overtly female – and that requires a closer

look.

Gabriel’s rich vestments are predominately red, the color traditionally worn by

Mary Magdalene in Mediæval works. The hair is auburn red, styled with lovely long

curls, quite like the hair of the Mary in the Ghent altarpiece interior triptych (whom I

believe to be Jesus’s wife); the mother Mary has thin locks of uncombed brown hair.

The angel’s eyes are brown, as with those of the Ghent interior Mary, while the

betrothed wife of Joseph has the green eyes of the exterior Mary, who is

unquestionably

Jesus’s

mother. And Gabriel

wears a sumptuous jewelstudded golden crown,

surely fit for a king or

queen, while Mary has but

a simple circlet not even

made of gold – this is

strange because angels

rarely if ever were painted

with crowns at all, let alone

such an obviously royal

tiara, while in the Ghent

Mary the wife and the

united androgyne Christ in

its center panel do have

comparably

ornate

crowns. These matters

raise the question whether

the same woman was

chosen to model for

Gabriel who had posed for that interior Mary in the Ghent – as I compare the two

sets of features I conclude that they are identical. That raises another question, whether

van Eyck intended the viewer who was wise to the truth about Jesus’s wife occluded

by organized Christianity to realize that this angel Gabriel is being closely associated

with Mary Jesus’s bride.

̅̅̅̅ PLENA, which abbreviates the

Gabriel’s greeting to Mary is written AVE G𝑅𝐴

angel’s salutation in Luke 1:28, Ave gratia plena, “Hail, full of grace!” And Mary’s reply,

also provided, is ECCE ANCILLA D𝑁̅I, Ecce ancilla Domini, “Behold the handmaiden of

the Lord”, in verse 38. This Mary’s response is universally assumed to be selfreferential – “Behold in me the handmaiden of the Lord” – but I see no reason to

discount the possibility that van Eyck, as always loading up his canvases with an

abundance of symbol pointing to the original faith in Jesus-and-Mary, is instead

suggesting that each figure is speaking of the other: that just as Gabriel speaks of Mary

as “full of grace”, Mary calls Gabriel, or perhaps really the Magdalene, “the

handmaiden of the Lord”.

�The outermost wings of the main register of the Ghent altarpiece, past a pair

of images of virgins playing instruments and singing, are occupied by Adam and Eve,

the forerunners of Jesus and Mary. The physical appearances of Eve and Mary are

quite the same – the same cloud of long red hair, the same facial features, and no attempt

that I can see to differentiate the two as was done with the two Marys – and I cannot

help but think that this was intended. I believe that the viewer was meant to see Mary

as the “new Eve”; and while in the much later dogma this was transferred either to the

mother or to “the Church”, the “new Eve” in the Apostolic tradition was indeed the

younger Mary. One could argue that in van Eyck’s time and place he would have had

to adhere to the dogma and present this Mary as the older woman or else “the Church”

but, with everything about this image pointing to the Magdalene, I cannot agree.

Danny Praet notes in The Ghent Altarpiece (ed. by Praet and Maximiliaan P. J.

Martens; footnote 64 on page 347), that this altarpiece was unveiled for the birth of

Joos, second son of Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy, which is significant because

an ancestor, Girart comte de Roussillon, was unable to produce a child, but according

to the Legenda Aurea Mary Magdalene miraculously intervened to save the Burgundian

line, and he managed to produce an heir in 771. In gratitude Girart founded the basilica

of Sainte-Madeleine at Vézelay, which claimed to hold some of Mary’s remains until it

was supplanted by its rival at Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume.

If I am right, despite the lack in this work of the customary identifying detail

of the alabaster jar of ointment, that this is Mary the wife rather than Mary the mother,

then whence would Jan van Eyck have derived such a radical notion? Duke Philip the

Good sent him abroad on some kind of secret mission between 1426 and 1429, and

Till-Holger Borchert (Van Eyck) and Lotte Brand Philip (op. cit.) theorize that it was to

the Holy Land, given the obsession of Philip the Good, van Eyck’s patron, with

managing a crusade to the Holy Land, and also the accurate depictions of Jerusalem in

van Eyck’s paintings thereafter, including the center panel of this altarpiece, the entire

work being formally presented just three years after his return. I surmise that van Eyck

could have learned about Mary the wife in Jerusalem but, given the frowningly

censorious attitude of his Flemish Protestant overlords, he put the information into

subtle visual clues of the kind that I am summarizing.

Yet another such clue is found in the realistically depicted wallpaper (the

technical term for art historians being “diaper”) behind Mary: here and there in its

design of flowers and leaves a banderole (an unrolled scroll used to present a title, a

description, or the words being spoken by a depicted individual) appears bearing the

word premitæ, Latin for “the one sought”, perhaps a misspelling of premitiæ, “the first

of its kind” or “the first-fruits”. Jesus did indeed seek her, in order to unite with her

as the redivivus of the first of humankind. Yet where the word appears above and to

the right of Mary’s book there are hints that the letter e was repainted and originally

was an o; this o is more clearly seen where the word appears below and to the right

of the book. This would make the word promitæ, “the promised one”, either in the

sense of “the one foretold/prophesied” or “the one betrothed”.

Nor is this the only apparent instance of word-change in these three portraits.

The diaper in the central panel, the one that features the figure whose identity is the

focus of the lustiest scholarly debates, features a repeated image based on the ancient

belief that a mother pelican would strike her breast with her beak until it bled, thereby

feeding her starving children, even at the cost of her own life; this belief often became

a metaphor for the resurrected messiah. Above the pelican is a banderole with, the

diaper has the phrase IHEꞚVS X𝑃̅S. Scholars assure us that this means “Jesus Christ”,

the second word being a nomen sacrem, a sacred word abbreviated out of respect,

meaning “Christ”. Antoon Vanherpe, who specializes in study of this altarpiece, tells

�me in private communication that it was not uncommon for artists in this time and

region to mix Greek and Latin letters in the same texts. While I agree that the phrase

was intended to mean “Jesus Christ”, I see some serious issues which are not as simple

as the mixing of Greek and Latin letters and which, unfortunately, I fail to find

mentioned in any scholarly writing that I have consulted:

Jesus’s name in Greek is actually written ΙΗΣΟΥS, which would be IĒSOUS in

Latin letters. However the name as painted here is IHEꞚVS is nonsensical: in Latin

letters it would be IĒESUS. assuming the fourth letter is meant to represent a sigma. It

looks like the artist responsible was unfamiliar with Greek, and so he took the Latin

form of Jesus’s name, IESVS, and did his best to try to imitate its Greek form. That

the script used is rather different from what was first written, and from what appears

in the panels to either side, suggests that this was written in a later time.

First, he inexplicably put both the Latin E and the Greek eta, H, instead of just

one or the other, depending on what language in which he meant to write the word.

Second, he tried to imitate an epsilon, Σ, with Ꞛ, which seems to be a minuscule

epsilon, ε with a vertical line affixed to it.

Third, he retained the Latin spelling of the end of the name, -US, failing to add

the omikron, O, and painted a Latin S rather than the proper Greek form of a final sigma,

C (which is more familiar today in a similar form, ς).

All of these clues tell us clearly that the painter was familiar with the Latin

IESUS, but only barely acquainted with the Greek, ΙΗΣΟΥS, so in his mind he started

with IESUS and did his best to adapt it, making it look something like the Greek form.

It is hard for me to believe that such ignorant sloppiness could have been

possible in the van Eyck workshop, which strove hard and well for accuracy and

realism, and which elsewhere manages Greek acceptably well. By contemporary

reports Jan was reasonably good with Greek. These issues, then, urge a careful look

into the possibility that another word originally was painted here, that someone after

Jan van Eyck’s time changed the original text to what we see today, no doubt in order

to bring it into line with dogmatic conformity.

Such a close analysis of the two words is borne out by studying the superb

analytical images taken with X-radiography, as well as those done by

macrophotography and reflectography in infrared light, which are serving as a guide

for a major restoration of the altarpiece “Lasting Support, An Interdisciplinary Research

Project to Assess the Structural Condition of the Ghent Altarpiece”

(closertovaneyck.kikirpa.be). The X-radiographic image shows clearly that another set of

words was painted first. This source reveals the first word to have originally been УHC,

a perfectly correct nomen sacrum (sacred abbreviation) in Greek letters that stands for

Jesus’s name. After that word, at the apex of the arch-shaped inscription, is +, either

representing the crucifixion or a conjunction meaning “and”, or both. Then comes a

second word: but while the УHC is reasonably clear in nearly every instance, the second

word is always obliterated, even to the point of round gouges dug into the material

beneath the paint, and not always in the same exact spot, proving that this is aggressive

erasure and not the remains of an original letter. This suggests to me that somebody

wanted to make it absolutely certain that no one would ever know what that original

word was; the individual must have been aware that sometimes in art works the first

version can show through later revisions, if the new paintwork is not thick enough, or

if over time it abrades away. There are in fact examples of both here and there in this

altarpiece. My suspicion is that such a vigorous eradication was to avoid giving offense

to dogmatic orthodoxy, and such a motivation would necessarily have been that of a

later revisionist painter, not Jan van Eyck himself. After effecting this brutal erasure,

this artist replaced УHC + with the misspelled IHEꞚVS, and added X𝑃̅S in place of the

�mysterious final word, giving us the badly misspelled but doctrinally safe “Jesus

Christ”.

Nothing is certain about the original second word, but the way it appears in

the X-radiographic image beside the figure’s right hand raised in blessing shows what

looks to me like a mu, Μ, with an erasure so ruthless that it has apparently left a gouge

in the substrate, dug in from above since the gouge is shaped like a teardrop. This

gouge takes out the “v” in the middle of the M, but leaves visible the two verticals on

either side. The У can also be made out beneath the final sigma, S, of the word painted

�over. The same words as they appear to the right of the figure’s left shoulder clearly

show the M, but with the “v” utilized as the upper half of the X (chi) in the revised

word, and it much more clearly shows the iota, У, under the S. In both cases, the second

letter of the second word seems to be the same P, the Greek letter rho, that was retained

in the middle of the replacement word, X𝑃̅S, or else possibly its Latin equivalent, R.

This hypothetical analysis would give us a complete original inscription of УHC

+ ΜΡУ, no doubt with overlines in both words, as required by the standard way of

indicating nomina sacra. These sacred abbreviations would represent УΗΣΟΥC and

ΜΑΡУΑ. Put into English, the two words are of course “Jesus” and “Mary”, and the +

between them is not merely to indicate a separation of words; it is the symbol of the

cross on which Jesus died, Mary affixed to a post by his side, after which they lived

again and became one. It may even have been used to represent the word “and” (et in

Latin, και [kai] in Greek), since the + symbol was just beginning to become popular

for this purpose in the fifteenth century. Since the artist who reworked this inscription

could theoretically have left УHC in place and simply changed the ΜΡУ to X𝑃̅S if he

thought of the + as representing the cross, for in that manner the phrase would stand

for Jesus Christ with the adornment of a cross. But it seems he understood the symbol

as meaning “and”, and sin e “Jesus and Christ” would certainly not do, he filled the

space left by the + by converting УHC into his nonsensical IHEꞚVS.

If the above argument has any merit, then the figure in the central portrait is

that of the risen messiah, the conjoined Jesus-and-Mary, about whom van Eyck could

well have learned during his travels on behalf of Philip the Good. But there is yet more

in support of this conclusion.

The central figure’s mantle has a lower border at the feet with these words

̅ ΑΝΧIΝ Y ΡΕΧ ΡΕΓ𝜈̅ Δ ΓΙ ΡΕΓΙΝΕ Δ

painted as if embroidered and set with pearls – 𝛪𝛪

M ΡΕΓΙΝΙ ΔΝaNX ΔΝΟ – which is hard to read because of the folds in the mantle, the

abbreviations, the odd spellings, and the mix of Greek and Latin letters. I take the Δ

as a way of repeating a previous letter-combination and Y as standing for ET (“and”),

and reconstruct the text in strictly Latin words and letters as [CO]N[IUN]XIN ET REX

REGINA DE REGUM REGINÆ CONIUNXIN (“Spouses and King-Queen of KingsQueens Spouses”). The first phrase refers to a king and queen (singular) who are

spouses (plural) of each other. The second phrase refers to their subjects, who are

likewise also pairs of spouses (plural) who are likewise kings and queens (plural).

Needless to say this brings to mind the “Lord of Lords and King of Kings” phrase in

Revelation 17:14 and 19:16 (the order is reversed in the latter). A textual issue is that

in classical times, when the Revelation was first composed, “king” and “lord” were

essentially the same thing, and the result is that in Aramaic, the tongue in which the

work was written, this phrase is mildly redundant. I suggest that the Urtext of these

verses said, rather than ( ܡܪܐ ܕܡܪܘܬܐmrā d’mrwtā), “Lord of Lords”, the

orthographically similar ( ܡܠܟܬ ܕܡܠܟܬܐmlkt d’mlktā), “Queen of Queens”. While some

of my reading of these words in the painting is tentative, still the certain reference to

ΡΕΓ𝜈̅ (“Queen”) and ΡΕΓΙΝΙ (“Queens”) certifies that the phrase suggests a unity of

male and female. Indeed, not only this inscription at the bottom of the mantle, but

also the blood-red garments and the “diadem of many” imaged in Revelation 19:1213 assure me that van Eyck used this description of the messiah, the “Word of God”

as verse 13 says, as his source. And this image is of course of the united messiah who

is also described in Revelation 1:13-16. (A discussion of these verses is found on pages

###ff.)

On the floor between this figure’s feet lies a crown, whose meaning in the

painting is another subject of scholarly controversy. I note that it is similar to the crown

on Mary’s head in the portrait to the viewer’s left – not identical, certainly, but likewise

�embossed with square and diamond-shaped jewels circled by pearls, and the living lilies

and roses now turned to beautiful goldwork. It is quite as if Mary has put down this

her first crown as superseded by a new crown representing her new larger nature, no

more an individual but a united being in the image and likeness of Elohim. This seated

figure bears instead a tripartite crown that shortsighted scholars assume symbolizes

the trinity of dogma, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. That it does not. This crown is

instantly recognizable as the traditional triple crown worn by the popes from the

fourteenth century (though it had simpler antecedents) until 1963; it is usually said to

represent the pope’s offices as universal pastor, universal ecclesiastical judicator, and

temporal potentate. But it is also, even more possible, that this figure is meant to

portray the original Apostolic teaching of the Father and, in his image and likeness,

the Son and the Daughter (the Paraclete, Mary), before the Daughter was replaced

with a vaguely male Holy Spirit. Indeed it is very possible that Jan van Eyck learned

during his travels of the Apostolic origins of the organized religion’s eventual dogma

in the Father, and the Son, the latter two joined together in the image and likeness of

the first.

However very interestingly the same crown is sometimes associated with Mary,

either the mother or the wife, such as in the central panel of a triptych in the church

of Saint-André de Cologne, illustrating the Virgin of Mercy, often referred to as the

Confrérie du Rosaire (Confraternity of the Rosary), painted between 1510 and 1515. This

lovely work by a talented artist known today only as the Master of Saint-Séverin has

so many similarities to the Ghent altarpiece made a century earlier that I think they are

deliberate. Two angels lower the same triple crown down onto Mary’s head in three

not-yet-conjoined rings, while on either side of her the triptych shows groups of

adoring faithful similar to the choirs of musicians in the Ghent, while behind her torso

is a “diaper” styled just like those in the altarpiece. But which Mary is this, shown just

as in the final form of van Eyck’s work in a blue gown with the long curling red hair

of the Magdalene? By blending the triple crown of the Ghent central figure with the

beautiful young bride of the left-hand panel the Master seems to me to imply that he

sees the central figure of the Ghent as in some way intimately connected to Mary.

There may also be in this central figure’s headgear a suggestion of the white

turban of the high priest that first Jesus wore (beginning in John 19:2), and then Mary

(beginning in the restored verses that replace 20:18), though I see no sign of the tiara

of gold that was affixed to it, which had engraved on it קדש ליהוה, “Holy to YHWH”.

Whether or not this crown or mitre is the high priest’s turban, there can be little doubt

that its placement evokes the opening visions in the Revelation: this is the united

messiah who appears to John in 1:13-15 (see the discussion of its identity on page

###), who is seated in majesty in 4:9 when the twenty-four elders cast at its feet their

own crowns, the only Biblical reference to crowns at the feet of a royal person. The

imagery is not specific to that of the Revelation because I think van Eyck wanted also

to embrace what I say in the last paragraph about Mary’s new crown. But still the mitre

and the vestments bring to mind the visionary figure dressed in ephod and turban with

tiara. But Revelation 1:13’s reference in the Greek version to a garment that reaches

to the feet and a golden sash at the breasts is answered in this portrait.

The sash as depicted bears the word SABAωTH, which again emphasizes this

male-female unity. The altarpiece’s spelling, mixing Latin and Greek letters, reflects

how the word is written in Greek, σαβαωθ (sabaōth) in Greek, which transliterates the

Hebrew ( צבאותṣbāwt). It is commonly found in the Tanakh in conjunction with the

name ( יהוהYHWH), and is usually translated into English as “Lord of Hosts” or “Lord

of Armies”. However the lexeme (root) ( צבאṣbā) has the root meaning of combining,

integrating, unifying, and growing as a unit. From this lexeme come words that

�unsurprisingly mean bundles of grain ( )צבתand an aggregation of a certain article ()צבר,

but also a verb meaning to dip into water or to be wet ()צבע, a verb meaning to share

something with someone else ()צבט, a verb meaning to wish or desire something ()צבא,

a noun that indicates beauty or honor ()צבי, or something that is desired or desirable

()צבו. By further application it refers to the gazelle ( )צביfor its beauty and its tendency

to herd together in close-knit groups. In sum, scholars are wrong to focus only on the

meaning of soldiers coming together into an army acting in a unified manner as a single

entity, especially in regard to this painting, in which no sign of a military application of

this word is to be found, and which in any case does not have the name יהוהjoined

with it – which it would if this figure were indeed God. Therefore I think that the

appearance of the word on the altarpiece evokes its root concept of joining together

into unity as a composite single entity – in other words, of Jesus and Mary coming

together as the redivivus of the original human being of Genesis 1:26-27 in the image

and likeness of God – and thus, in these last words, its Biblical application to יהוהis

invoked. The use of this word, correctly but oddly spelled, suggests to me that Jan van

Eyck heard about it (rather than reading about it) during his apparent visit to the Holy

Land mentioned above. [NOTE: This matter of Jesus and Mary becoming the redivivus

of the androgyne created in Genesis 1:26-27 is the main theme of the Gospel of John

as reconstructed in the book from which this passage is taken. –Ed.]

The descriptive phrases in three arcs of gold over this central figure’s head are

as follows, first as they appear line by line, then with the many abbreviations written

out in full, then with a careful translation into English. Note a: that the first line in the

painting extends to a second indented line in my transcription; b: that the second line

originally with a red cross-shape (+) as does the first but that it only clearly appears in

the X-radiographic image and only faintly in the final painting, and c: that the word

INMENSAM is broken between the second and third lines.

̅̅ OPTl9 PP

̅ DEVS POT E

̅ TISSIM9 PP DIVIN A

̅ MAIESTAT E

̅ + SV

̅ 9 O ̅̅

+ HIC E

IM

̅ ITATE

̅

DVXCEDIS̅ BO

(+) REMVNERATOR LIBERALISSIMVS PROPTER INME

NSAM LARGITATEM

+ Hic est Deus potentissimus propter divinam maiestatem + summus omnium optimus

propter dulcedinis bonitatem

(+) Remunerator liberalissimus propter inme

nsam largitatem.

+ This is God most powerful by means of the divine majesty + the highest (and) the best of

all humanity by means of the agency of the sweetness of his [God’s] goodness.

(+) The most liberal recompenser by means of the imme

nse generosity.

Notes for the Latinist reader: I assume that the small sign which looks like the

raised numeral 9 and that ends three words in the first line represents the conjugation

ending -us. The abbreviation PP in the first line likely stands for propter, which appears

in the third clause, but it might also be the standard abbreviation for per procurationem;

either way, the meaning is the same. And I assume that omnium, as in all standard Latin

dictionaries, refers here to “all humanity” because otherwise this adjective, as merely

meaning “all”, would be entirely unclear as to what or whom it applies to.

This inscription includes three clauses with an identical structure. The first two

clauses appear in the first line, and the third clause is divided between the second and

third lines, in fact splitting the word inmensam between them. The identical structure of

these three clauses includes first an affirmation about the figure in the portrait, then

the abbreviation PP or the word propter for which it apparently stands, and then an

�affirmation about God, the author of the benefit to humanity that this figure

represents:

The Figure:

Conjunction:

This is God most powerful

by means of

The highest and best of humanity by means of

The most liberal recompenser

by means of

God:

the divine majesty

the sweetness of his goodness

the immense generosity

The first clause in the first line makes no sense if it is understood as saying that

this is God through the agency of God (of “the divine majesty”); I read it as referring

to the image and likeness of God made by the agency of God in Genesis 1:26-27

and/or to its redivivus, the united messiah Jesus-and-Mary.

The second clause in the first line refers quite clearly to the “highest and best

of all”; if one insists on reading this inscription as referring specifically and only to

God, then here it would have to be taken as saying in effect that God is the highest

and best of all gods, which certainly would have been entirely unacceptable. As

mentioned in the notes for the Latinist reader, I see this word with its common sense

in the language of referring to all humanity. And in that case this clause is again clearly

referring to that first human being in the Genesis creation story and/or the resurrected

messiah Mary-and-Jesus.

The third clause, which appears in the second and third lines of this arc, is a

third description of this human being in the image and likeness of God, this time as a

recompenser in the sense of Isaiah 40:1-2, that the faithful are recompensed by Jesusand-Mary through “the immense generosity” of God, by means of this united messiah

in the image and likeness of God, humanity is rewarded with the gift of eternal life. I

see here no hint of the doctrine of penal substitutionary atonement enshrined in

mainstream Christianity, which says that Jesus died in order to absolve humanity from

the inevitable punishment of its roster of sins; since these three portraits seem to show

the Apostolic theology, which has nothing like that dogma, it does not appear here –

though I suppose conservative religious autocrats might have assumed that it was

implied and nodded with pleasure.

What is more, this interpretation refers not to the central dogma of mainstream

Christianity of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit but rather to the personæ of Elohim

and of Jesus and Mary, in which the latter two are joined together in the image and

likeness of the first. Still, this text seems carefully composed such that this message,

which could well have been deemed heretical, would be less likely to offend. And,

though my interpretation goes against the mainstream interpretation of art historians,

I find it supported by the many clues I analyze in these three portraits. One clue is

found in this central painting’s other inscription, found on the riser of the dais beneath

this figure:

̅T SN

̅ SENECTVTE I̅ FRONTE * GAVDIV

̅ SN

̅ MERORE

VITA SINE MORTE IN CAPITE * IVVE

̅ TIO

̅ RE A SINISTIS

A DEXTRIS * SECVRITAS SN

Life without death in the head/beginning, was found without sad old age in the brow, joy

without sorrow to the right, security without fear to the left.

Again, a cursory reading by the ecclesiastical dogmaticians and censors would not find

anything specifically objectionable in this phrase, but to anyone who recognized and

understood the gnosis, the secret wisdom that Jan van Eyck was illustrating, would

apprehend the very specific message in these ostensibly vague words. The first phrase

speaks of eternal life, the life in the Æon Jesus said could be reëntered through uniting

with the other by means of love: Jesus’s spirit entered into Mary’s head (in capite) after

his resurrection, such that together they were the redivivus of that androgyne made by

�Elohim in the beginning (in capite). And note that the “to the right” and “to the left”

phrases are to be taken quite literally: the portrait of Mary to the right (from the

viewpoint of this central image) promises “joy without sorrow”, and the image that I

think was originally of Jesus to its left guaranteed “security without fear”, which is not

an attribute associated with the Immerser, thus certifying that that image was at first

of Jesus, a matter to which I will turn after one last matter.

Indeed, joy seems to be often associated by the gospels with Mary. Matthew

28:8 has the women who saw Mary-as-angel in the tomb feel “fear and great joy” as

they go to the male disciples. In John 16:20-24 Jesus uses the analogy to the pregnant

woman there with them, who is Mary, to say the grief they will feel at Jesus’s death will

be replaced by unmitigated joy. But most interesting, and probably the text the artist

had in mind, is Hebrews 12:2, which says Jesus αντι της προκειμενης αυτω χαρας υπεμεινεν

σταυρον αισχυνης καταφρονησας εν δεξια, “endured a cross and disregarded the shame” of

it – and the word αντι (anti) is usually translated “for the sake of”, but it really carries a

core sense of something that is beside or opposite the subject, and thus by extension

“instead of” or “in exchange for”, while the verb προκειμενης (prokeimenēs) means “set

before” in the visual sense, “put in position before his eyes”; these two words clearly

refer to how Mary was tied to a stake beside Jesus so she would be forced to watch

his slow suffering execution. If then “the joy” in this verse refers to Mary, then the

verse says that he braved the incredible agony of this death by fixing his gaze on the

joy of his beloved wife, that also he accepted that death “instead of” her, “in exchange

for” her. And then the verse adds τε του θρονου του θεου κεκαθικεν – the first word, τε

(te), is an enclitic conjunction usually translated here as “and”, but which really means

either “both” or “and both”; this I think is the sense here: that both Jesus and Mary

“took a seat at the right hand of the throne of God”. The verb in this clause, κεκαθικεν

(kekathiken), is of course taken by all translators as conjugated in the third person

singular of the perfect, but I see it here as in the third person plural of the extensive

pluperfect, which is best put into English with the simple past tense. With all this in

mind I translate the entire verse thus: “… as we look to the one who founded and

completed the faith, Jesus, who endured a cross and disregarded the shame (of it) being

across from the joy set before his eyes, and that both of them took a seat at the right

hand of the throne of God.”

If my thinking is reasonable, then we should expect that at least in the early

stages of this work’s creation there might have been some indications of a feminine or

androgynous nature to this person. That brings me to a careful study of the images

published so far by the aforementioned project to study the older layers beneath the

surface painting in order to guide restoration of the altarpiece. Infrared photography

shows but few differences, while the X-radiographic results provide evidence of a

number of minor alterations that were made between the first rendition of this portrait

and the final painting that we see today. However there is one major difference that

needs consideration here is that the earlier version of the central figure has no beard

or at the very least it has much less of a beard. The underlip, chin, neck, and left cheek

are without a beard or very nearly so, and the mass just below the middle of the chin

is gone or reduced, and the left jawline is visible, though these are all obscured by the

beard in the surface painting. In the radiographic image the entire right side of the

face, including forehead, eye, and cheek, is dark, which could suggest a beard, though

it seems unlikely that a beard would be painted in on one side of the face but not the

other. When with computer programs I intensify the contrast and the lightness of the

radiographic image there is little to nothing that suggests a beard on the face’s right

side either. Both the finished painting and this underpainting show highlights on the

figure’s left side, by which the painter indicates that the face was illuminated by a light

�source coming from the figure’s left, such that the right side of the face is relatively

shadowed. In both versions, at the top of the left ear, above the left eyebrow and

cheekbone, along the ridge of the nose, on the lower lip, on the left side of the chin

and throat there are clear painted highlights. The right side of these features are shaded

for contrast. The clothing is shaded on the right shoulder (also darkened by the long

hair draped on the shoulder) and the head casts a shadow on the golden arc behind it.

In this context, the darkness on the right side of the face is not that of a beard but

rather the typical shading technique used by portraitists to give contour and depth to

an image. The mouth is fuller and may be slightly open, as in the images of Mary and

the supposed John on either side of this central panel. And the upper lids of the eyes

are half-closed, the eyes directed downward, quite as a woman in earlier times was

trained to keep her gaze lowered. The nose is narrower and more delicate, again all just

like those of Mary. The effect of these latter gives the face something of an Eastern

Mediterranean or even an Ethiopian look, a realism of cultural heritage that the West

would not see until Rembrandt, who strove to make his Biblical subjects look like

Mizrahi Jews, probably using as models Jewish and Muslim friends who had escaped

the pogroms in Spain. If Jan van Eyck did indeed travel through the East he would

have familiarized his artist’s eye with the look of such people. While I cannot be

certain, this X-radiographic image does suggest that the face as van Eyck originally

painted it was decidedly more Eastern and more feminine in nature, but that it was

revised to make it more like a typical Western European male.

In addition, the ornate high neckline of the tunic in the surface image is absent,

and in its place is a simple curved black line, possibly representing a choker such as a

woman would wear. And, by the coloration and similar tonal highlights painted below

this line, identical to what is above the line, it seems to be bare skin below just as it is

above, and presumably continuing down to where the V of the ends of the amice come

together at about the sternum, and it seems more feminine for this much of the figure’s

chest to be revealed. An equivalent to the ornate high neckline in the surface image is

found instead bordering the edge-trims of the amice in the V, coming together directly

beneath the huge medallion that also appears in the surface image, technically an

epigonation, serving in both inner and outer designs like a brooch to hold the amice

in place. These differences also imply a relatively more feminine original design.

The frame to the viewer’s right is confidently identified by all scholars as John

the Baptist; his traditional cognomen in English; I prefer John the Immerser because

“Baptist” only transliterates the Greek rather than translating it, and implies a later

Christian ritual and a much later Protestant denomination that lay far in his future.

This identification seems obvious since the words in the arcs of gold over his head

confirm that this is the Baptist. And yes, the ikonic motif called Deësis, which presented

�a “trinity” of Virgo, Christus Pantocrator, and Baptista could be seen in the East, and it is

possible that van Eyck saw one in Greece or Anatolia, though I know of no evidence

that he was in those regions. But since other than this supposed Deësis the motif does

not otherwise appear in the West, which makes it hard to believe that those who had

commissioned this altarpiece desired it, or that in this group of three there was a

theological statement that meant anything in the West. One should wonder why Mary

and the Immerser are given equally high status on either side of (supposedly) Jesus. I

suppose that one could argue that they were both forerunners: Mary gave birth to him

– for the standard belief is that this is the mother – and John immersed him to begin

his year of ministry and teaching. One could also emphasize the fact that the

predecessors to the present-day Saint Bavo Cathedral in which the altarpiece is

displayed had a traditional association with John the Immerser. Yet if I am right that

this Mary is the wife, she who became wholly united with her husband in the image

and likeness of Elohim, then that elevates her in importance far beyond the Immerser.

My suspicion is that underneath some massive work to cover him up with an

enormous amount of hair and beard there lurks the original presence of Jesus, he who

was likewise united with Mary to bring that image and likeness into being. And indeed

the images taken as part of the restoration project suggest that in the underpainting

there was considerably less hair and beard, since the lips, forehead, and cheeks are

more visible, as well as the last letter in MUNDI and the [D]N̅I that precedes TESTIS to

the right of the figure’s head, partly obscured by the abundant hair in the painting as

we see it today.

The descriptor in three arcs over this portrait is likewise quite problematic. It

appears verbatim thus:

̅ BAPTISTA IOHE

̅S ∙ MAIOR HOĪE ∙ PAR ANGL̅IS ∙ LEGIS

+ HIC E

̅MA ∙ EWĀGELİİ SACIO ∙ APL̅OR VOX ∙ SILĒCIV

̅ PRHETAR

SV

̅ I TESTIS

LVCERNA MVNDI [D]N

The Latin is not hard to reconstruct from the abundant abbreviations, with two

exceptions.

First, the word SACIO seems to lack the usual overline to indicate an abbreviation,

and I am persuaded by E. H. L. Aerts (“Het lam Gods der gebroeders Van Eyck”,

Verslagen en Mededeelingen, January 1920) that it stands for SANCTIO, “sanctification”.

Second, only two and a half letters of

the penultimate word appear in the

radiographic image if not beneath the massive

hair of the final portrait. The letters 𝑁̅ I are

clearly seen in the underpainting, and before

it what must be the upper part of an R P, or D,

but not an O, because what we see is much too

horizontally elliptical. Still, this is enough to

confirm the usual reconstruction of [D] N̅ I,

DOMINI (“the Lord”); the overline on the N

represents the missing letters.

With these hypotheses in place, I

expand and translate the descriptor thus:

HIC EST BAPTISTA IOHANNES, MAIOR HOMINE, PAR ANGELIS, LEGIS

SUMMA, EWANGELII SA[N]C[T]IO, APOSTOLORUM VOX, SILENCIUM

PROPHETARUM,

LUCERNA MUNDI, D[OMI]NI TESTIS.

This is John the Baptist, greater than human, equal to the angels, of the law

�its summation, of the gospels their sa[n]c[tific]ation, of the apostles their voice, of the

prophets their silence,

of the world its lamp, of the L[or]d his witness.

All of the analyses by art critics I have consulted are so satisfied with the first

phrase, and assume without question that this is John the Immerser. They fail,

however, to consider carefully the implications of the rest of this descriptor – yet it

should be obvious to anyone with the feeblest grasp of the Christian scriptures and

the standard doctrines that never is John said to be greater than humanity or equal to

the angels; though, yes, Jesus calls him the greatest of humanity, he quickly adds that

the least of those in heaven, including angels presumably, are greater than John

(Matthew 11:11). Nor is the Immerser ever the summation of the law, though Paul

many times declares this of Jesus. Jesus calls John “a burning and shining lamp … for

a season” (John 5:35), but only the united messiah of Mary-and-himself is named by

Jesus as “the light of the world” (John 8:12). The same is true with the rest of these

attestations, other than the last. I am sure that, minus the first phrase, HIC EST

̅ I TESTIS, most people would

BAPTISTA, and perhaps also the last phrase, D[OMI] N

assume that these phrases describe Jesus. More on these two in a moment.

This text was plainly adapted from a sermon about John the Baptist given by

a fifth century bishop in Ravenna, Petrus Chrysologus, which van Eyck may have read

during his foreign traves. This sermon characterizes John only as a worthy exponent

of the nature and teachings of Jesus imparted by dogma. I have underlined the

elements that appear in the altarpiece:

Iohannes[,] uirtutum scola, magisterium uite, sanctitatis forma, norma iusticie, uirginitatis

speculum, pudicicie titulus, castitatis exemplum, penitencie uia, peccatorum uenia, fidei

disciplina, legis summa, ewangelii sa[n]c[t]io, apostolorum uox, silencium prophetarum,

lucerna mundi, officium preconsis, preco iudicis, Domini testis, tocius medius trinitatis.

John[,] the school of his (Jesus’s) virtues, the authoritative teaching of life (which is) the model

of his sanctity, the norm of his justice, the mirror of his virginity, the title of his modesty, the

example of his chastity, the way of his penance (which is) the forgiveness of sins, the discipline

of his faith (which is) the summation of the law, the sanctification of the gospel, the voice of

the apostles, the silence of the prophets, the lamp of the world, the duty of his proclamation,

the heralding of his justice, the witness of his Lord, (who is) the middle of the whole trinity.

Note the liberal use of the genitive in this series of qualities, noted by “his” in

the translation; by the context, the “his” refers to Jesus. Phrases in which the genitive

does not appear are essentially parenthetical, explaining what precedes. So “the

authoritative teaching of his (Jesus’s) life” is illustrated by “the model of his (Jesus’s)

sanctity”. So the manner of “the way of his (Jesus’s) penance” is said to be “the

forgiveness of sins”. Likewise, the five contiguous underlined phrases that follow “the

discipline of his faith” characterize that discipline, and “the middle of the whole

trinity” further identifies “his Lord” as the son of God. In the translation I have

replaced commas with a parenthetical “(which is)” to make this clearer to the reader.

With two exceptions, van Eyck has taken from Petrus only the phrases that

characterize Jesus, adding “John the Baptist” to them. These must have been selected

and at least sketched in position into the arcs overhead while still the portrait was of

Jesus. In addition, the identification of BAPTISTA IOHANNES was added to the work

after that change of identity from Jesus to John, and the phrase And also at some time

the very brief phrase [D]𝑁̅I TESTIS (“the witness of his Lord”) was also borrowed from

Petrus, rather than officium preconsis, preco iudicis, or tocius medius trinitatis, simply because

only it was short enough to fit into the limited space left once Jesus’s hair had been

enlarged to the wild coif of the Immerser.

�It also strikes me as very odd that the Immerser is identified as BAPTISTA

IOHANNES (“the Baptist John”), an inversion of the usual order that may appear thus

somewhere in the relevant literature but, if it does, I have never encountered it. The

reversal serves no purpose and I think must be an error – especially if the painter –

van Eyck or the later editor – were preparing this text in a hurry and/or if he were

focused more on covering up evidence of earlier wording that now must be

obliterated, such as that the portrait was originally of Jesus. I see no evidence in the

images of the underpainting of such, but of course a first pencil sketching would not

necessarily show even in X-radiography.

In sum, then, I

conclude that this

portrait was originally

of Jesus, flanked by an

image of Mary to the

viewer’s

left,

and

between them the

resurrected

messiah

who is Jesus and Mary

united. I also must

conclude again that it is

sad to see how often

academics care not to

call upon the contents

of their cranial cavities.

The underpainting

of the alleged John the

Baptist portrait, as

revealed

by

Xradiography, shows the

garment beneath the

outer cloak with edges

much more sharply

defined than the rough

borders of the camelhair

in the surface image.

This garment also has

more and narrower

folds, again with the

shadows within the

folds

in

crisper

definition,

which

suggests that it is woven

cloth, not fur. If that is

so, then the figure loses

the only certain trope

associated with the

Immerser, raising the

option that it is Jesus

instead.

Had these portraits been contrived with the typical Western tropes of that

time, and had these figures been Mary (either Mary) and John the Immerser, they

�would have been shown with haloes, but God (if the individual in the central frame

were meant as God) would of course not wear a halo. But instead we have here all three

depicted radiating rays of light, which indicates not just an intimate connection but an

equality or a common identity among all three of them. If the central figure is assumed

to be God, then we have a resulting concept that is found nowhere else, one that

probably would have been rejected as heretical: that the outer two figures are in some

way on the same level as God. If however the right-hand figure were Jesus and the

central figure were the risen messiah, with the spirit of Jesus within Mary, then the

sun-rays would make sense, since – according to the original faith of the Apostolic

(non-Pauline) communities that followed Jesus’s teachings in the first centuries C.E.,

especially in the East that Jan van Eyck apparently visited – Mary and Jesus united at

the resurrection into a composite, thus becoming in the image and likeness of Elohim,

and it, the resulting androgyne, would be shown here emitting light because according

to the Talmud that first human being was made from the light created in Genesis 1:3.

But I cannot think of any reason why the Immerser would be given such a singular

honor.

Rarely if ever is the Baptist portrayed in art reading from a book, but this

individual has a book in his lap. All too often it is said to be the Bible, open to Isaiah

40, presumably because verses 3-5 are paraphrased during the opening scene with the

Immerser in John 1:23. This identification is probably because the only legible word

in this painted book is the first, CONSOLAM𝑇̅, and scholars lazily make the assumption

– apparently not bothering to confirm it – that this is the first word in Isaiah 40:1. That

it is not; rather, the Latin says:

Consolamini consolamini populus meus

dicit Deus vester (“‘Be comforted, be

comforted, my people!’ says your

God”). Worse yet, many modern

sources even declare that the book

shows Isaiah 40:3-5, even though as

I said nothing is actually legible

other than the one word. In fact,

nowhere in the Latin Bible is there a

word that could by any stretch be

abbreviated as CONSOLAM𝑇̅, let alone

at the beginning of a verse, even less

at the head of a chapter.

Other than this single word what appears on this page of the book is painted

only to resemble words, but nothing can be read, so the only clue that van Eyck

provides us is this word. But it is, in my view, clue enough: it brings to mind the

consolament, as it was called in Occitan, the ultimate sacrament of the Cathars, who

would have still been recent memory in the early fifteenth century – a sad memory in

van Eyck’s Protestant world, one that remembered how they had been genocided out

of existence by their rival Roman Catholics. By the consolament the recipient received

and united with the Holy Spirit, the paraclete (in fact, the word consolament is derived

from the Occitan word by which “paraclete” or “comforter” was translated), becoming

a called boni chrétien (“good Christian”), boni homine (or bonhomme, “good man” and

woman), or ami de Dieu (“friend of God”), or a parfait or parfaite, a word which doesn’t

mean “perfect” in the modern sense, but rather “complete”, “whole” or “united”.

Also contributing to my unwillingness to accept this identification is the fact

that just as Mary’s face is identical to that of Eve in one of the outermost panels, so

too underneath all the hair John’s facial features closely resemble those of Adam – the

�eyes are identical other than the easily changed color of the irises, the brows are

identical, the same creases appear between the brows, the bridge of the nose has the

same outward curve halfway down, and the mouth is shaped the same, slightly open

in the same way, revealing identical teeth.

What is more, if this figure is indeed John, then it is for the second time that

he appears, but just as the Mary in the outer panels of the closed wings does not appear

on close inspection to be the younger Mary within but rather Jesus’s mother, so too

the John on the outside, presented en grisaille in imitation of a sculpture and helpfully

labelled as JO𝐻̅ES BAP, at a glance obviously has a different identity – the clothing is

completely different, including how the camel’s hair of his inner garment is depicted,

and the outer John has his hair and beard in artful helixes rather than the rough mass

of the man’s hair and beard in the interior portrait – a rough mass that I think serves

more to hide than to indicate character.

This portrait said to be of the Immerser, but which I think originally was of

Jesus, also has a clue-word in the diaper, the wallpaper behind him. This word appears

twice, the first half to the figure’s right (prim …) and the second half to his left (… us),

hence primus (“the first”), which complements the word behind Mary, premitæ (“the

one sought”, or possibly premitiæ (“the first of its kind”) or promitæ (“the promised

one”). And indeed Jesus-and-Mary restore to existence the primus, the first of

humanity.

There is also the matter of placement – on either side of these three central

panels this register includes a paired set showing angels singing and playing

instruments, and on either side of them are Adam and Eve. Since the lower register of

paintings has an overall unity in the “story” it tells – which I do not discuss herein – we

should, I think, expect the upper register likewise to have an obvious overall theme to

draw it together, but by the standard interpretations it does not. I will now suggest one

that does.

My contention is that these three panels originally showed, Mary the wife on

the left, Jesus the husband on the right, and the united messiah who comprised both

of them in the middle. Adam and Eve are shown on the far ends, outside heaven or

the Æon, indicated by the two panels of musical angels, since they are no longer united

into one being. Next within, and so within paradise, are Mary and Jesus, united in the

central figure.

After studying carefully the eyes of the three portraits between the angel

panels, I conclude that Mary’s eyes are obviously deep brown, distinguishing them

from the blue eyes of Mary the mother and suggesting that these are two different

Marys; and that the eyes of Jesus in the right-hand portrait (he who was revised after

the life of van Eyck into John the Immerser) are just as certainly bright blue-hazel. But

the eye-color is not certain in the figure in the middle, whose identity is so much

debated by the academics, who I believe is the united messiah Mary-and-Jesus. I have

studied the image magnified as high as I can manage, and used a number of methods

in my image editing programs, and my conclusion is that the left eye has an undercoat

of brown with blue-hazel highlights added (especially to the viewer’s left) and the right

eye was given an undercoat of blue-hazel with brown highlights added (especially at

3:00, 7:00, and 10:00). Of course this is just what I see, and other viewers likely will see

these eyes differently. But the certain facts are these: Mary’s eyes are inarguably deep

brown, and Jesus’s eyes are just as certainly bright blue-hazel, yet the eyes of this central

figure are not distinctly one color or the other. And I conclude that that is precisely

what van Eyck intended: that they appear to be a blend of the two colors, and since

of course he could not have gotten what I believe he wanted by mixing brown and

blue-hazel oil paints (the result would be a lighter brown), he chose, as I see it, to paint

�the eyes one bluehazel and one

brown and then

apply to each

touches of the

color of the other.

Another

topic to consider in

reference to my

contention

that

these three panels

originally showed,

from left to right,

Mary, the united

messiah, and Jesus,

is that of skin

color.

As

established herein,

Mary, being on her

father’s side of

Amazigh ancestry,

was evidently very

dark-skinned, even

black, but with red

hair and very

probably blue eyes.

I should begin

consideration of

this matter by

emphasizing that

there would have

been

nothing

strange about the

first two with

African coloration

at that time in

Europe. As I have

previously

discussed,

there

had long been a

tradition of black

madonnas in the

subcontinent long

from before van Eyck’s birth, which continued to flourish for a few centuries more.

Though many were destroyed by misguided Protestant reformers, hundreds still exist

today. In his native Belgium alone, not far from Ghent, there are no fewer than nine

black madonnas. When he travelled through France, Spain, and Italy on behalf of

Philip the Good he surely visited many churches and must have seen countless more

black madonnas. So, in that context, van Eyck may have decided to represent the left

and the central figures likewise with Ethiopian skin tones, without fear of ecclesiastical

anger given these many Black Messiahs.

�However given the established fact that some later painter, no doubt under

orders from the ecclesium, repainted many aspects of the Ghent altarpiece clearly to

tone down some of the more obvious hints of the standard dogma flouted in the

images. Among these, I think, the skin colors of the left and central figures likely were

whitened to match that of Northern Europeans. Such artistic censorship has gone on

forever – elsewhere herein I discuss how Mary beside the crucified Jesus was in one

of the Rabula Gospels miniatures turned into a bearded thief, and the intensely

offensive whitening of the Black Madonna of Chartres. Another obvious example is

that of the flying doilies added to some paintings to cover the genitalia of the painted

figures. And the occasion of this Caucasian invasion would be a generation or two

after van Eyck, when the black madonnas were less of a “thing” and when dogma was

again moving into hard and judgemental conservatism – the time of the Protestant

Reformation and the Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation.

The question to ask, then, is whether the aforementioned subsurface studies

of the Ghent altarpiece bear out this possibility. The answer, mine at least, is that it is

hard to say. I converted the surface images of the three to black-and-white and

balanced the albedo of the clothing such that it was equal in each case to its equivalent

in X-radiography (to the right in the nearby images), and the faces and hands of all

three figures appear to be darker in

the latter set of images. This could be

ascribed to a common painterly

technique of sketching in a dark

underpainting first and then adding

the lighter skin color on top, making

this layer thinner where shadows are

required, and then adding the smaller

details, such as hair and eyelashes. But

this cannot be the reason in this case,

because the latter details are all visibly

in place, and besides this

underpainting technique became

common after van Eyck’s life, in the

Baroque period.

Mary’s neck and upper chest appear

somewhat lighter than the very dark blue

tunic beneath, which would be about the

case with someone of African complexion,

and her neck is especially dark even though

there are no shadows on it in the final work.

Her right hand is about the same tone as the

red sleeve past it, which is also as we might

expect. Jesus’s right hand, in the right-hand

panel, is lighter than the supposed camel fur,

and about the same as the green cloak,

which seems to be a lighter color of skin.

And the central figure’s face and hands are

certainly darker than the deep red robe. In

sum, while I cannot be sure, the indications

at least to my eyes could point to the

proposal above. I hope that further study –

�such as, if future technology ever makes it possible, studying the original images in full

color – will inform this matter.

As an aside, this comparative study of the originals and the final forms of the

paintings made even to me clearer the androgynous or even feminine characteristics

of the central figure.

While La Fuente de Gracia, the so-called Fountain of Grace (sometimes

“Fountain of Life”) painting also produced by the Jan van Eyck workshop resembles

the Ghent altarpiece in some ways, the significant factor related to discussion of the

latter is that every single one of its clues to help us identify the three figures are gone

in this later work – there are no arcs of gold over their heads but rather the westwork

of a grand cathedral; there is no SABAωTH sash, no reference to “Queen of Queens”,

no УHC + ΜΡУ. Mary, whichever Mary she is meant to be, is dressed in plain blue rather

than a bridal gown; the triple crown on the head of the middle figure is now unitary

and the crown at its feet is replaced with the lamb said to share the throne of God

(Revelation 5:6); and the third portrait, which I think started as Jesus and became John

the Immerser, is in La Fuente John the Evangelist. The lower register shows a group of

orderly, pious Christians with the pope in front (wearing the tripartite crown missing

above) confronting the high priest at the head of a group of unruly Jews, drawn as ugly

caricatures, clearly about to flee in terror, on either side of the titular fountain of the

waters of life (Revelation 22:1). Everything always depends upon the person or

institution commissioning the work; while in this case it is not certain, it is surely not

the relatively liberal-minded Philip the Good but likely Enrique IV of Castile and León

for the Monastery of Santa María del Parral in Segovia which he founded; it would be

a reasonable hypothesis that the conservative Roman Catholic king understood these

clues enough to disapprove of them, in that the evidence suggests that he demanded

a copy be made without them – indeed, their noticeable complete disappearance from

La Fuente helps to confirm their meaning as discussed above.

The visual arts can often be truly revolutionary in nature precisely because their

emotional impact can be so great, and also because clues can be hidden that escape

the attention of the censors but register in the minds of those who look for them. So

it amazes me and yet it does not amaze me how art has helped keep alive the truth

about Mary-and-Jesus through the centuries, from the earliest catacomb and

sarcophagus art through wall paintings in churches, through Leonardo and van Eyck

and Bosch, and even to recent times, especially in the brilliance of William Blake.

�

James David Audlin

James David Audlin