Number 18 Year 2022

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF

TURKOLOGY

RESEARCH and STUDIES OF ISLAMIC INSCRIPTIONS

Études et recherches d’épigraphie islamique

İSLAMİ KİTABE ARAŞTIRMALARI

مجلة دراسات الكتابات والنقوش اإلسالمية

İLTERİŞ KUTLU KAĞAN

İLTERİŞ)

KUTYAZITI

BULUNDU

(

Publicatiıon of SOTA

ISSN 1570-694X

sotapublishing@gmail.com

�INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TURKOLOGY

nr. 18

Eylül / September 2022

next issues will be published in December 2022

RESEARCH and STUDIES OF ISLAMIC INSCRIPTIONS

Études et recherches d’épigraphie islamique

İSLAMİ KİTABE ARAŞTIRMALARI

مجلة دراسات الكتابات والنقوش اإلسالمية

ISSN 1570 694X

Chief-editor: Mehmet Tütüncü

Editors: Ahmed Ameen (Fayoum University), Lotfı Abdeljouad (Tunis), Zeynep Öztürk (Istanbul),

Torbjorn Ødegaard (Oslo), Mehmet Emin Yılmaz (Ankara)

Editorial board:

Ahmet Bican Ercilasun (Ankara), Murad Adjabi (Alger), Ludvik Kalus (Paris), Frederic Bauden (Liege) Ahmet Ali Bayhan (Ordu), Ahmet Taşğın (Ankara), Mehmet Akif Erdoğru (Izmir), Sami Saleh

Abdelmalek (Cairo), Ibrahim Yılmaz (Erzurum), Hatice Aynur (Istanbul), Mehmet Ölmez (İstanbul),

Andrey Krasnozhon (Odessa), Olga Vasileva (St. Petersburg), Moshe Sharon (Jerusalem), Machiel Kiel

(Bonn), Timur Kocaoğlu (Michigan), Andrew Petersen (Wales), Ardian Muhaj (Tirana), Fathi Jarray

(Tunis)

Contact:

e-mail: sotapublishing@gmail.com

Postal address:

SOTA

Brabantlaan 26

2101 Sg Heemstede

Netherlands

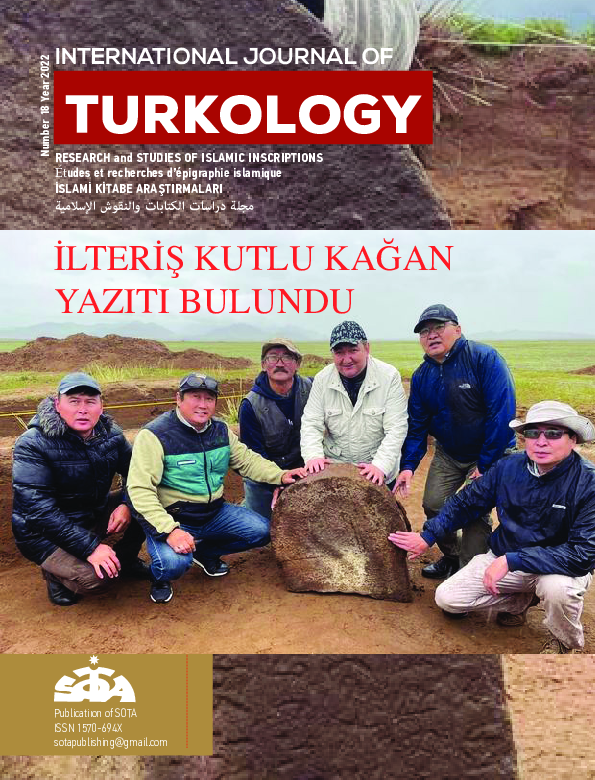

Cover; New Dıscoverd Insciption in Mongolia and its excavation team under leadership of Darqan

Qydyrali (chairman of Turkic Academy of Astana)

2

EY L ÜL - S EPTEM B ER 2022

�CONTENTS / İÇİNDEKİLER

Turkology.042022.ID0081

HABERLER

İLTERİŞ İKUTLUG KAĞANA AİT KİTABE BULUNDU

4-13

Turkology.042022.ID0082

Khalida Mahi

PROBLEMS OF IDENTIFICATION OF THE “MASTERS OF TABRIZ

14-32

Turkology.042022.ID0083

Mehmet Tütüncü

AVUSTURYA KUNSTHİSTORİSCHES MUSEUM’DA BULUNAN

İZVORNİK FATİH SULTAN MEHMED CAMİSİNİN KITABESİ

34-36

Turkology.042022.ID0084

Mehmet Tütüncü

THE INSCRIPTION OF THE ZVORNİK FATİH SULTAN MEHMED MOSQUE

IN THE KUNSTHISTORISCHES MUSEUM IN AUSTRIA

37-40

Turkology 042022.ID0087

Sadi BAYRAM

XVII. ASIRDA SULTANİYE MÜDERRİSİ, MÜFTÜ, ŞÂIR, MUTASAVVIF AMASYALI

KOCA MÜFTÜ, DİYE ANILAN ‘İDİZÂDE, ÂKİFZÂDE MUSTAFA EFENDİ VE ESERLERİ

41-100

�PROBLEMS OF IDENTIFICATION OF

THE “MASTERS OF TABRIZ”

Khalida Mahi

Independent Scholar in Islamic Art History

Abstract

Famous and enigmatic at the same time, this is how the “Masters of Tabriz” could be defined. They are

well-known because they are associated with the splendid Ottoman tiles of the 15th and 16th centuries

but the identity of these ceramists remains mysterious in many respects. Their denomination is itself

a problem, it comes from the signature Ustādān-i Tabrīz inscribed in the Yeşil Cami of Bursa (1424).

Therefore, generally, it refers only to the craftsmen who produced this masterpiece. However, this same

name covers in fact four groups of ceramists who worked mainly in Bursa, Edirne, Istanbul and Jerusalem

for almost a century and a half. We could of course think they are from Tabriz, but this designation is

misleading because they are not all from this Iranian city. It is not only their geographical origin that is

controversial, but also several aspects of their history. Indeed, certain architectural tiles which they have

not signed give rise to problems of attribution and consequently lead to further questions concerning

their artistic route through the Ottoman lands and neighbouring regions. Even the few monumental

signatures are subject to discussion because they do not necessarily designate ceramists, thus making the

reconstitution of these different groups more difficult. The “Masters of Tabriz” did not leave a biography

and this is the reason why a large number of hypotheses have been formulated since the beginning of

the 20th century. This study proposes a critical approach to all methods of identification in order to

distinguish between reliable and uncertain theories. The aim is to put an end to misconceptions as their

puzzling history gives rise to imaginary stories.

This study was presented at the 16th International Congress of Turkish Arts held in Ankara in 2019,

but was not published because the congress editorial board required an original topic. Indeed, I already

had the opportunity to write about the “Masters of Tabriz” in Eurasian Studies in 2017, however the

approach is different. The previous article mainly focused on rereading ancient texts and monumental

inscriptions as some of them were subject to extrapolations and hasty deductions which necessarily

falsified the identification of these ceramists. As for this present paper, it exposes and shows the limits of

all identification methods (monumental signatures, names of artists in the archives, nisba, comparative

study of ceramics, ancient texts, monumental inscriptions) which can indeed be interpreted in different

ways and generates false notions.

What we know concretely about the “Masters of Tabriz” comes down to rare monumental signatures

and brief information drawn from ottoman archives. With so few given materials, the researchers were

forced to use other methods of identification. They have logically started their investigations based on

these scarce tangible evidences. Indeed, the names of the craftsmen seemed to be an element that could

14

EY L ÜL - S EPTEM B ER 2022

�provide answers. Ahmed Tevhid studied the inscriptions of the Yeşil Külliye of Bursa and his records

made it possible to read the signatures of the Ustādān-i Tabrīz and Muḥammad al-Majnūn who are part

of the first group of the “Masters of Tabriz” as well as those of two other artists: ʿAlī ibn Ilyās ʿAlī and

ʿAlī ibn Ḥājjī Aḥmad Tabrīzī1. The names of some members of the third group are revealed in a book of

accounts in which are registered the craftsmen in the service of the royal palace of Istanbul during the year

1526. Ḥabīb Tabrīzī and his ten assistants appear there in the corporation of ceramists. Another Ottoman

archive, not dated but which was among other sheets from the early 16th century, mentions a list of

craftsmen from Tabriz. ʿAbd al-Razzāq and Burhān are registered there as ceramists and more precisely

as tile cutters (kāşītrāş)2. The ceramists of the second and fourth team are unnamed.

These documents have the advantage of specifying their profession. On the other hand, the names inscribed

in the buildings are more difficult to interpret because they may belong to the calligrapher, the decorator,

the architect or the ceramist3. In the end, these signatures leave their authors anonymous and the medium,

on which they are written, sometimes remains the only way to suggest the function of the protagonists.

The Ustādān-i Tabrīz are unanimously considered as ceramicists because their name is written on the

imposing miḥrāb made entirely of ceramic tiles (Fig. 1). It is also this function that should be attributed to

Muḥammad al-Majnūn because his two signatures are located in a space full of tiles that cover the walls

and the ceiling of the Sultan’s lodge (Fig. 2). However, this method of identification can be invalidated

because the location of the signatures can be arbitrary. For example, an artist who carves a minbar does

not necessarily indicate his name on this element, but he may choose to engrave it on the door of the

mosque4. It is for this reason that several trades have been attributed to Muḥammad al-Majnūn5. The case

of ʿAbd Allāh al-Tabrīzī illustrates also this hesitation. He signs an inscription on a ceramic panel in the

Dome of the Rock6 (Fig. 3). As a result, he was granted the function of ceramist and was naturally included

in the group of “Masters of Tabriz”. However, it is very likely that he is the calligrapher who wrote the

inscription. It is the same for ʿAlī ibn Ḥājjī Aḥmad Tabrīzī whose name engraved on the wooden door

of the Yeşil Türbe would suggest that he is a wood carver. However, he is also designated as ceramist,

decorator and calligrapher7. From this observation, it is not surprising that different professions have been

assigned to all these people, which certainly creates confusion.

Their name is frequently followed by a nisba linked to Tabriz, which has incited some specialists to

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Tevḥīd, 1911.

The archives TSMA D. 9784 and TSMA D. 9706-1, fol. 22b-23a were discovered by Chukru,

1933-34, 51-52, and are published in Uzunçarşılı, 1986, pl. 1; pl. 21.

Porter, Soustiel, 2003, 242.

Mayer, 1958, 17-19.

Arseven, 1952, 151; Ünver, 1955, 15.

Van Berchem, 1927, 335-336.

Gabriel, 1958, 99; Aube, 2017, 195.

E YL Ü L - S E PT E M O B E R 2 0 2 2

15

�consider this particle as an obvious explanation of their place of origin8. By definition, a nisba indicates

the origin of the people who assume it but this can be interpreted in various ways. Indeed, it can refer

only to their ancestors without themselves being directly linked to the said city. In this case, we cannot

confirm that they were born, lived or worked there. To increase their chance of being hired, the craftsmen

could also choose a nisba linked to a famous city where the craft and skill are recognized. Tabriz is

incontestably linked to the cultural and intellectual prestige going back to the Il-khānid and Jalā’īrid

rulers who elevate it to the rank of capital between 1265 and 1432. Its glorious period continued in the

15th and 16th centuries under the Qarā Qoyūnlū, Aq Qoyūnlū and Safavid dynasties. Craftsmen would

therefore find it advantageous to say that they were from Tabriz without actually being from this city

and without having received artistic training there. To be certain that the nisba actually indicates their

geographical origin, it would have to be corroborated by archaeological testimony or written sources

because this particle, by itself, cannot be considered as proof9.

There is no hesitation to designate Tabriz as the city of origin of Ḥabīb Tabrīzī since it is stated in the book

of accounts. But for the majority of other artisans, no written source indicates their places of provenance.

Then, a comparative study of the architectural tiles was essential to establish artistic affiliations which

have confirmed that the craftsmen were from Iran and Central Asia10. There is no doubt that they came

from there, but often the problem was to find out precisely from which cities. The fact that a style, like

the “international Tīmūrid style” which was widely used, has made it possible to propose different cities

of the Persian world but also of Anatolia11 to explain the origin of ceramists. On the other hand, the lack

of archaeological evidence on some sites prevents comparisons and Tabriz illustrates this situation. It

has often been considered as the hometown of the Ustādān-i Tabrīz but the earthquakes have destroyed

several buildings there that prevent artistic parallels. Moreover, the fact that the history of certain ceramic

techniques is not well known prevents us from going back to their creation workshop, which would allow

ceramists to be linked to a specific production centre. This is the case of the “black line” technique, which

was introduced into the Ottoman world in the 1420s, and where lack of knowledge authorizes several

theories on the origin of the Ustādān-i Tabrīz.

Despite its weakness, it is the comparative method that was used to answer the question of the artistic

route of these ceramists through the Ottoman world, because to trace their itinerary, it is impossible to

rely on their signatures which are only in the Yeşil Cami. Most of the buildings they have decorated are

dated, in a fairly good state of conservation and offer remarkable tile ornamentation. It is undoubtedly

8

9

10

11

16

Migeon, Sakisian 1923, 248; Lane, 1939, 156; Denny, 1977, 14.

O’Kane, 1987, 39.

Aslanapa, 1971, 211; Meinecke, 1976, 103; O’Kane, 1987, 66; Necipoğlu, 1990; Golombek,

Mason, Bailey, 1995, 183.

Kiefer, 1956, 18-20; Babinger, 1992, 467.

EY L ÜL - S EPTEM B ER 2022

�the quality of the tiles, using various techniques, that motivated the researchers to learn more about

these skilled masters. They mainly work for the royal family and the pashas and the majority of their

artworks are located in Bursa, Edirne and Istanbul, while a smaller number of decorated buildings are

found in Gebze, Bozüyük, Kütahya, Konya, Karaman and Jerusalem. Attributions are generally well

established and accepted by researchers. However, some of their artworks are controversial because

similar ornaments may be the work of other craftsmen working in the same artistic spirit as the “Masters

of Tabriz”. Did the first group make the tiles of the Fatih Cami (1463-1470) (Fig. 4)? Did the second team

decorate the mausoleum of Mahmut Paşa (1474)? Have the reused panels in the Sünnet Odası (15271528) been designed by the third team or by the Iznik workshops? These are the kind of questions that

still generate discord among specialists. The ceramics in the mausoleum of Yakub Bey II in Kütahya

(1429) and in the imaret of Ibrahim Bey in Karaman (1432) (Fig. 5-6), which seem to have been made

by the first group of the “Masters of Tabriz”, are also subject to controversies.

Since their name remains laconic and stylistic comparisons can be interpreted in different ways, it was

essential to find answers in ancient texts: historical source, embassy account and biographical dictionary

were then exploited. By reading these documents, the researchers provided important insights into the

historical and artistic context of that time and they allowed an idea of how the artists arrived in the Ottoman

world. However, some of these written sources have led to extrapolations and uncertain speculations.

Yet these have been accepted and considered as conclusive elements, which obviously misrepresent

these ceramists. These problems of interpretation are encountered in the text of ʿĀşıḳpāşāzāde, Ottoman

historian of the 15th century. He writes that foreign artists were invited by Ḥācī ʿİvaż Pāşā, who was the

vizier of Mehmet I and the architect of the Yeşil Külliye:

اثار حاجى عوض پاشا آل عثمان قاپوسندہ پاشالر سنلرلن شولن چكمكى اندن اوكرندلر وهم دخى غير اقليمدن اهل هنرلر

واوستادلرى اوّل رومه اول كتورمشدر وهم قاز اوادہ بر مدرسه وبر زاوية ياپدردى وبروسدہ بر مسجد وبر مدرسه ياپدردى

12

.وجماہ اوقافندن م ّكة اللهك فقراسنه مبلغ اقچه تعين اتدى وهر يلدہ كندررلر

Deeds of Ḥācī ʿİvaż Pāşā:

At the Ottoman court, the pashas learned to host receptions [where the guests were served] in

Chinese ceramics. [Ḥācī ʿİvaż Pāşā] was also the first who took talented artists and master

craftsmen from other parts of the world to Anatolia (Rūm). In Ḳazova [in the province of Tokat],

he built a medrese and a zāviye, while in Bursa, he built a mosque and a medrese. In addition,

thanks to his vaḳf, he increased his income whose profits were sent each year to the poor in

Mecca.13

12

13

ʿĀşıḳpāşāzāde, 1929, 197.

Translated by Michele Bernardini.

E YL Ü L - S E PT E M O B E R 2 0 2 2

17

�In the 1930s, Franz Taeschner mentions this document in his study written in German, and it is from

there that art historians draw information often without returning to the original text. Relying on this

source, Franz Taeschner only indicates that artistes were brought from the east to Bursa14. However, his

comments were later extrapolated to justify the provenance of the ceramists from Tabriz15. The ancient

text provides no such details nor any other geographical precisions, so it cannot be used to demonstrate

their place of origin. The nisba of the Ustādān-i Tabrīz is not much help in this case either because the

lack of archaeological evidence in Tabriz does not allow linking the Yeşil Külliye’s ceramic tiles to this

city. The closest artistic connections are located in Samarqand, as other hypotheses have suggested16 (Fig.

7-8).

Apart from the Ottoman archives cited above, the other ancient sources, as precious as they are, remain

approximate because the “Masters of Tabriz” are not clearly mentioned there. However, the researchers

believe they have distinctly identified them and this inevitably leads to problems of assimilation. Thus,

ʿAlī ibn Ilyās ʿAlī, whose name is written in an inscription of the Yeşil Cami, has constantly been

confused with ʿAlī al-Naqqāš (Nakkaş Ali in modern Turkish literature) who appears in the book of

Ṭāşköprüzāde17. It is certain that he played an important role in the ornamentation of the mosque, given

the size of the epigraph (170cm x 90cm) and its privileged location above the Sultan’s lodge overlooking

the prayer hall:

( قد تم نقش هﺫہ العمارة الشريفة بيد أفقر الناس علي بن إلياس عليA)

( في أواخر رمضان المبارك سنة سبع وعشرين وثمانما ٔٮةB)

(A) The decoration of this noble edifice was accomplished by the hand of the most humble of men,

‘Alī ibn Ilyās ‘Alī,

(B) in the last days of the blessed month of Ramaḍān of the year 827 (mid to late August 1424)18.

The word naqš ( )نقشtranslated by decoration, has caused confusion because it can be applied to several

decorative practices: it can refer to a painted, drawn or even sculpted decoration on any support19. It is for

this reason that all professions related to architectural decoration have been assigned to him, including

that of ceramist. However, he should be seen as a designer who created and coordinated the entire

decorative program of the Yeşil Cami. Indeed, when we observe the harmony of the decorative work in

the mosque, it seems that only one person, in this case ʿAlī, has created the patterns that are deployed

14

15

16

17

18

19

18

Taeschner, 1938, vii.

Atasoy, Raby, 1989, 83; Blair, Bloom, 1995, 144; Crane, 2009, 343.

Golombek, 1997, 582-584; Bernus-Taylor, 1997.

Taşköprüzāde, 1927, 280; Taşköprüzāde, 1985, 437-438.

Translated from the French version in Mantran, 1952, 93.

Taeschner 1932, 151; Grabar 1996, 23; 135, note n° 31.

EY L ÜL - S EPTEM B ER 2022

�on wall paintings, ceramic tiles, stucco, wood and marble20. Researchers have different opinions on his

artistic involvement, however they almost all agree to recognize him as ʿAlī al-Naqqāš. His identity was

discovered by Gaston Migeon and Armenag Bey Sakisian in 1923 in the work of the poet and biographer

Beliğ Bursalı, written in Ottoman in 1723 and which relates the life of the royal family and the notables

of Bursa21. This author relies mainly on the biographical dictionary of Ṭāşköprüzāde, written in Arabic in

1558 and dedicated to the intellectual and religious elites, where mention is made of ʿAlī al-Naqqāš for

the first time. The writings of Ṭāşköprüzāde were translated into German in 1927 by Oskar Rescher and

it is from this translation that Franz Taeschner draws his information on which all the specialists rely22.

Ṭāşköprüzāde does not directly relate the life of ʿAlī al-Naqqāš, but mentions him succinctly through the

“biography of his grandson Lāmi‘ī, famous poet and writer notably author of Şehrengiz Bursa:

” ” الالمعي:الشيخ المي چلبى – ومنهم الشيخ العارف باهلل محمود بن عثمان ابن علي النقاش المشهور بـ

كان جدہ علي من مدينة بروسا ولما دخل األمير تيمور مدينة بروسا أخﺫہ معه وهو صغير إلى بالد ما وراء النهر

. وتعلم هناك صنعة النقاش وهو أول من أحدث السروج المنقوشة في بالد الروم

23

Al-šayḫ Lāmī Čelebī- in the category of sheikhs: Maḥmūd ibn ʿOthmān ibn ʿAlī al-Naqqāš, known

as al-Lāmi‘ī. His grandfather ʿAlī was born in the city of Bursa. When Tīmūr entered this city, he

took him with him to Transoxiana while he was still a child. There he learned the art of naqš. So,

on his return, he was the first in Anatolia to apply this art on horse saddles24.

The correlation between the two people is easy to accept because they have the same given name and the

inscription in the mosque indicates that a certain ʿAlī was in charge of the naqš. It was therefore tempting

to think that his nickname was ʿAlī al-Naqqāš. The concordance is reinforced by the fact that they both

lived in the same period: ʿAlī ibn Ilyās ʿAlī completed his artwork in 1424 as stated in the monumental

inscription and the ancient texts situate the events during the entry of Tīmūr into Bursa in 1402 and the

return of ʿAlī al-Naqqāš which took place after 1411. We know that he returned to Anatolia after this date

thanks to an edict promulgated on 25 August 1411 by Uluġ Beg, grandson of Tīmūr, which authorizes

Muslim craftsmen and intellectuals to leave Samarqand and reach their homeland or other destinations25.

Moreover, the ceramics of the Yeşil Cami are doubtless inspired by Tīmūrid models from Transoxiana

(in which Seljuk elements of Anatolia are integrated). This would tend to show that ʿAlī al-Naqqāš

actually participated in the ornamentation of the mosque in Bursa after having stayed and acquired artistic

20

21

22

23

24

25

Taeschner 1932,151; Taeschner 1938, vii-viii; Ünver 1955, 12; Lane, 1971, 42; Carswell, 1982,

76; Atasoy, Raby, 1989, 83; Necipoğlu, 1990, 136; Golombek, 1997, 580; Öney, 2003, 705.

Beliğ, 1885, 176-177; Migeon, Sakisian, 1923, 248.

Taşköprüzāde, 1927; Taeschner 1932, 166

Taşköprüzāde, 1985, 437.

Translated with the help of Sid Ahmed Mahi

Edict cited in Woods, 1990, 115.

E YL Ü L - S E PT E M O B E R 2 0 2 2

19

�knowledge in Transoxiana. It is for all these reasons that an analogy has been made between these two

people. However, it is important to precise that Ṭāşköprüzāde and Beliğ Bursalı never quote the name

of ʿAlī ibn Ilyās ʿAlī, which makes it possible to express doubts about this assimilation. If it seemed

necessary to biographers to indicate, in a very short text, that he was the first to introduce in Anatolia a

new decoration on horse saddles, it means that it must have been a significant event in his artistic career.

However, it is surprising that the authors do not mention his participation in the exceptional decoration

of the Yeşil Cami, which represents a major step in Ottoman art and symbolizes the return of Ottoman

power in Anatolia after the defeat against Tīmūr. It is therefore reasonable to consider that these two

people are not related.

The second group of the “Masters of Tabriz” was also confused with other characters identified in

an ancient source written in Persian and titled: Kāšī-tarāšān-i Ḫurāsān (Tile cutters from Khurasan).

This document has been read in 1981 by Faik Kırımlı26 in which he formally recognized the craftsmen

who made tiles of the Çinili Köşk (Tiled Pavilion) in 1472 and this parallel is accepted without being

questioned:

عرضه داشت

ساکن درگاہ کاشی تراشان خراسانی

... عرض نواب کاينات سالم... بعد از ادا دعا بر دوام دولت

معاد ميرساند که در اين مدت انواع پريشانی و زحمت...

کشيديم و روی قصر را بيراق خود بهم رسانيديم اکنون

در دل چنان است که خدمت آستانه جد و ابا الحضرت

همايون بجا آوريم و بروانه بيرون آمدہ که مهم اين فقيران سائل

و بخاطر رسول هللا و ائمه المومنين عليهم الصلواہ و السلم...

که مهم اين بيچارگان ساخته روانه آستانه گردانند

27

.... ... نخواهد کرد... ... ...

Request:

The resident of the court, the tile cutters from Khurasan. After praying for the sustainability of the

government ... and presenting greetings to the Lord of heaven ... During this time, I suffered all

kinds of sorrows and I hoisted the standard on the palace (I completed the work in the palace?)

and now we intend to go to the threshold of His Excellency’s court. We went out with the intention

of settling the affair of these poor questers ... Peace and salvation on the believers of the imams

and on the Messenger of God ... so that he deigns to settle the affair of these needy sent to the

court ... it will not make ...

26

27

20

Archive TSMA E. 3152 is published in Kırımlı, 1981, 106.

Transcribed and translated by Tirdad Hempartian.

EY L ÜL - S EPTEM B ER 2022

�The author of this letter writes on behalf of the tile cutters from Khurasan of which he is a member. He

complains to a sovereign about their precarious situation and he asks for help. This is not specified in the

petition, but they claim either to be paid or to have other orders. This document is indeed incomplete and

imprecise. It is the term qaṣr ( )قصرwhich means palace but also pavilion, as well as the mention of the

tile cutters which seemed to give sufficient clues to confirm that the ceramists mentioned in this letter are

those who decorated the Çinili Köşk. The text is not dated and the name of the sovereign is not given,

which prevents us from situating the events in a precise chronology and certifying that this is the period

corresponding to the construction of the pavilion of Istanbul. The name of the qaṣr is not specified either.

The architectural study of Sedad Hakkı Eldem reveals the existence of seventy-six Ottoman pavilions

mainly located in Istanbul, but also in Edirne, which were built between 1451 and 186528. The tile cutters

from Khurasan could then have decorated one of them and not necessarily the Çinili Köşk. This building,

unusual in Ottoman architecture, is inspired by the pavilions built in Samarqand at the end of the 14th

century. Fallen into ruin a century later, they are known through ancient texts, manuscript paintings

and archaeological evidence29. These cruciform structures with eight rooms opening onto a central hall,

like the Çinili Köşk, are called Hašt Bihišt (Eight Heavens)30. The ornamentation of the Çinili Köşk,

made of cut tile mosaic and bannā’ī brick, draws its inspiration from the arts of Tīmūrid Khurasan and

more from those of the Turkmen Tabriz. At the beginning of the 15th century, Šāhruḫ moved the power

from Samarqand to Herat and made it an important artistic centre. Upon his death, the Qarā Qoyyūnlū

sovereign, Jahānšāh, gradually seized Tīmūrid possessions and entered Herat in 1458 without annexing

it. Leaving Khurasan, he took with him the best craftsmen he installed in Tabriz31. There is indeed a

strong artistic continuity of this region with the decorations of Turkmen Iran in the second half of the 15th

century as witnessed by the ceramics of the Blue Mosque of Tabriz (1465) (Fig. 9-10). The collaboration

of ceramists from Khurasan and Tabriz in this mosque gives birth to ornamental particularities which are

reflected in the pavilion of Istanbul32 (Fig. 11-12). These artistic relations explain that the ceramists of

the Çinili Köşk came initially from Khurasan but the archive read by Faik Kırımlı cannot be considered

as proof of their geographical origin because there is no evidence of their link with the tile cutters from

Khurasan mentioned in the request letter.

The lack of tangible evidence and the fragility of the identification methods allow various opinions

on the “Masters of Tabriz”. The large number of hypotheses raised about their identity is undoubtedly

confusing. We have very little certainty about these craftsmen and most of the time we can only make

assumptions about them, but the multiple theories tend to make their story more complex than to provide

28

29

30

31

32

Eldem, 1969.

Bernardini, 1986, 186; Necipoğlu, 1991, 213; Golombek, 1995, 137, 145; Bernardini,1994,

237.

Golombek, 1981, 47; Bernardini, 1994, 238; 246-247.

Golombek, Wilber, 1988, xxiii; Aube, 2008, 247.

O’Kane, 1993, 252; Aube 2017, 79-95.

E YL Ü L - S E PT E M O B E R 2 0 2 2

21

�clarification. In addition, ancient texts have been subject to extrapolation and hasty deductions. However,

the unfounded allegations are not systematically questioned and are therefore wrongly considered as

conclusive evidence. Written in Ottoman, Arabic and Persian, the language barrier often prevents them

from being checked and discussed. This approach is problematic because it conveys misconceptions and

participates in the creation of myths. The methods of identification cannot be detailed in this paper, but

they are in the book I am currently writing about the “Masters of Tabriz”33. In this book, it is shown that

when precise and reliable primary written sources are not available, then the comparative method, despite

its limitations, remains the best way to understand the artistic affiliations that enable suggesting their

place of origin, to assign their artworks and trace their route through the cities of the Ottoman world and

neighbouring Anatolian emirates.

33

22

This book is the result of my doctoral researches, cf. Mahi, 2015, see also Mahi, 2017.

EY L ÜL - S EPTEM B ER 2022

�Bibliographical References

Arseven, Celal Esad., Les arts décoratifs turcs (Istanbul : Milli Eğitim Basımevi,1952).

ʿĀşıḳpāşāzāde, Die altosmanische Chronik des ‘Aşıkpaşazāde (Leipzig: Harrassowitz, 1929).

Aslanapa, Oktay, “Turkish Ceramic Art”, Archaeology, 24, n° 3 (June, 1971): 209-219.

Atasoy, Nurhan, Raby, Julian, Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey (London: Alexandria

Press/Thames and Hudson, 1989).

Aube, Sandra, “La Mosquée Bleue de Tabriz (1465) : remarques sur la céramique architecturale Qarâ

Qoyunlu”, Studia Iranica, 37 (2008): 241-277.

Aube, Sandra, La céramique dans l’architecture en Iran au XVe siècle : Les arts qarā quyūnlūs

et āq quyūnlūs (Paris : Presses de l’université Paris-Sorbonne, 2017).

Babinger, Franz, Mehmet the Conqueror and his Time (Princeton: Princeton University Press,

1992).

Beliğ Bursalı, Güldeste-i riyāz-i irfān ve vefiyāt-i dānişverān-i nādiredān (Bursa:

Hüdavendiğar Vilayet Matbaası, 1885).

Bernardini, Michele, “L’arte di costruire nel periodo timuride: artigiani e architetti alla corte di

Tamerlano”, Islàm, Storia e Civiltà, 4/17 (1986): 185-193.

Bernardini, M., “Il giardino di Samarcanda e Herat”, in Giardino islamico: architettura, natura,

paesaggio, ed. A. Petruccioli (Milan: Electa, 1994): pp. 237-248.

Bernus-Taylor, Marthe, “Le décor du «Complexe Vert» à Bursa, reflet de l’art timouride”,

Cahier d’Asie Centrale 3/4, (1997): 251-266.

Blair, Sheila, Bloom, Jonathan, The Art and Architecture of Islam. 1250-1800 (New York:

Penguin Books, 1995).

Carswell, John, “Ceramics” in Tulips, Arabesques and Turbans: Decorative Arts from the

Ottoman Empire, ed. Y. Petsopoulos (London: Alexandria Press, 1982), pp. 54-96.

Chukru, Tahsin., “Les faïences turques”, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramics Society, 11

(1933-34): 48-61.

Crane, Howard, “Art and Architecture, 1300-1453”, in The Cambridge History of Turkey. I.

Byzantium to Turkey, 1071-1453, ed. K. Fleet (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009),

pp. 266-352.

Denny, B. Walter, The Ceramics of the Mosque of Rüstem Pasha and the Environment of

Change (New York-London: Garland Publishing, 1977).

Eldem, Sedad Hakkı, Köşkler ve Kasırlar (Istanbul: Kutulmuş Maatbası, 1969).

Gabriel, Albert, Une capitale turque : Brousse, Bursa (Paris : E. de Boccard, 1958).

Golombek, Lisa, “From Tamerlan to the Taj Mahal”, in Essays in Islamic Art and Architecture in

Honor of Katerina Otto-Dorn, ed. A. Daneshvari (Malibu: Undena Publications, 1981), pp. 4356.

E YL Ü L - S E PT E M O B E R 2 0 2 2

23

�Golombek, Lisa, “The Gardens of Timur: New perspectives”, Muqarnas, 12 (1995): 137-47.

Golombek, Lisa, « Timurid Potters Abroad », Oriente Moderno, n.s. XV (LXXVI), 2 (1996): p. 577-586.

Golombek, Lisa, Mason, Robert, Bailey, Gauvin, “Persian Potters in the Ottoman World: New

Data from the Timurid Ceramics Project of the Royal Ontario Museum”, 9th International

Congress of Turkish Art, Istanbul, September 23rd-27th 1991 (Ankara: T.C. Kültür Bakanlığı

yayınları, 1995): 181-188.

Golombek, Lisa, Wilber, Donald, The Timurid Architecture of Iran and Turan (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 1988).

Grabar, Oleg, L’ornement: Formes et fonctions dans l’art islamique (Paris : Flammarion, 1996).

Kiefer, Charles, “Les céramiques musulmanes d’Anatolie”, Cahiers de la Céramique et des

Arts du Feu, 4 (1956): 15-30.

Kırımlı, Faik, “Istanbul Çiniciliği”, Sanat Tarihi Yıllığı, 11 (1981): 95-110.

Lane, Arthur, “The So-Called “Kubachi” Wares of Persia”, Burlington Magazine for

Connoisseurs, 75, n° 439 (Oct., 1939): 156-163.

Lane, Arthur, Later Islamic Pottery: Persia, Syria, Egypt, Turkey (London: Faber and Faber,

1971).

Mahi, Khalida, La céramique architecturale des «Maîtres de Tabriz» dans les édifices ottomans des

15ème et 16ème siècles (thèse de doctorat, Aix-Marseille Université, 2015).

Mahi, Khalida, “Les «Maîtres de Tabriz», céramistes dans l’empire ottoman: une mise au point sur leur

identification”, Eurasian Studies, 15/1 (2017): 36-79.

Mantran, Robert, “Les inscriptions arabes de Bursa”, Bulletin d’Etudes Orientales, 14 (195254): 87-114.

Mayer, Leo Ary, Islamic Woodcarvers and their Works (Geneva: Albert Kundig, 1958).

Meinecke, Michael, Fayenzdekorationen seldschukischer Sakralbauten in Kleinasien

(Tübingen: E. Wasmuth, 1976).

Migeon, Gaston, Sakisian, Armenag Bey, “Les faïences d’Asie Mineure du XIIIe au XVIe

siècle”, Revue de l’Art Ancien et Moderne, 43 (1923) : 241-252.

Necipoğlu, Gülru, “From International Timurid to Ottoman: A Change of Taste in SixteenthCentury Ceramic Tiles”, Muqarnas, 7 (1990): 136-170.

Necipoğlu, Gülru, Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power, the Topkapı Palace in the Fifteenth

and Sixteenth Centuries (Cambridge, Mass.,-London: The Mit Press/New York: The Architectural

History Foundation, 1991).

O’Kane, Bernard, Timurid Architecture in Khurasan (Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers; Undena

Publications, 1987).

O’Kane, Bernard, “From Tents to Pavilions: Royal Mobility and Persian Palace Design”, Ars Orientalis,

23 (1993): 249-268.

Öney, Gönül, “Ottoman Tiles and Pottery”, in Ottoman Civilization, ed. H. Inalcık (Istanbul:

24

EY L ÜL - S EPTEM B ER 2022

�Republic of Turkey, Ministry of culture, 2003), pp. 699-735.

Porter, Yves, Soustiel, Jean, Tombeaux de paradis. Le Shāh-e Zende de Samarcande et la

céramique architecturale d’Asie centrale (Saint-Rémy-en-l’eau : M. Hayot, 2003).

Raby, Julian, Yücel, Ünsal, “Chinese Porcelain at the Ottoman Court”, in Chinese Ceramics in

the Topkapı Saray Museum, Istanbul, Vol. I, ed. J. Ayers (London: Sotheby’s Publications;

Istanbul: Topkapi Saray Museum, 1986), pp. 27-54.

Taeschner, Franz, “Beiträge zur frühosmanischen Epigraphik und Archäologie”, Der Islam, 20 (1932):

p. 109-186.

Taeschner, Franz, “Preliminary Materials for a Dictionary of Islamic Artists”, Ars Islamica, 5,

supl. 1 (1938): iv-viii.

Ṭāşköprüzāde, Eš-Šaqā’iq en-Noʿmānijje (Constantinople: Phoenix, 1927).

Ṭāşköprüzāde, Eş-Şeḳā’iḳu n-Nuʿmānīye fī ʿUlemā’i d-Devleti l-ʿOsmānīye (Istanbul: Edebiyat

Fakültesi Basımevi, 1985).

Tevḥīd, Aḥmed, “Brūsada Yeşīl Cāmiʿ ve Yeşīl Türbe kitābeleri”, 1328 Sene-i Māliyesine

Maḫṣūṣ Muṣavver Nevsāl-i ʿOsmānī, IV (1328/1911) : 128-139.

Ünver, A. Süheyl, Yeşil Türbesi Mihrābı (824-1421) (Istanbul: Tege Laboratuvarı Yayınları,

1955).

Uzunçarşılı, İsmail Hakkı, “Osmanlı Sarayı’nda Ehl-i Hıref (Sanatkārlar) Defterleri”, Belgeler,

11, n° 15 (1986): 23-76.

Van Berchem, Max, Matériaux pour un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum, deuxième partie,

Syrie du sud. Tome II, Jérusalem “Haram” (Cairo : IFAO, 1927).

Woods, John E., “Timur’s Genealogy”, in Intellectual Studies on Islam: Essay written in Honor

of Martin B. Dickson, eds. M. M. Mazzaoui, V. B. Moreen, (Salt Lake City: University of Utah

Press, 1990), pp. 85-125.

Archives Documents

Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi Arşivi (TSMA)

TSMA D. 9706-1, fol. 22b-23a, “Cemāʿat-i kāşīgerān”.

TSMA D. 9784.

TSMA E. 3152, Dilekçe Metni, “Kāšī-tarāšān-i Ḫurāsān”.

E YL Ü L - S E PT E M O B E R 2 0 2 2

25

�Fig. 1-The miḥrāb of the Yeşil Cami, 1424, Bursa (© Khalida Mahi 2019)

Fig. 2- The Sultan’s lodge in the Yeşil Cami, 1424, Bursa (© Khalida Mahi 2019)

26

E Y L ÜL - S EPTEM B ER 2022

�Fig. 3- Signature of ʿAbd Allāh al-Tabrīzī in the Dome of the Rock, mid-16th century, Jerusalem

(© Khalida Mahi 2019)

Fig. 4- Detail of the ceramic panel in the Fatih Cami, 1463-1470, Istanbul (© Khalida Mahi 2019)

E YL Ü L - S E PT E M O B E R 2 0 2 2

27

�Fig. 5- The mausoleum of Yakub Bey II, 1429, Kütahya (© Khalida Mahi 2019)

28

EY L ÜL - S EPTEM B ER 2022

�Fig. 6- The miḥrāb of the imaret of Ibrahim Bey (Karaman), 1432,

nowadays conserved in the Çinili Köşk, Istanbul (© Khalida Mahi 2019)

E YL Ü L - S E PT E M O B E R 2 0 2 2

29

�Fig. 7- Façade of the mausoleum of Širin Beyk Āqā, 1385, Samarqand (© Khalida Mahi 2019)

Fig. 8- Tiles on the miḥrāb of the Yeşil Cami, 1424, Bursa (© Khalida Mahi 2019)

30

EY L ÜL - S EPTEM B ER 2022

�Fig. 9- Masjid-i Šāh, 1451, Mashhad (Khurasan) (© Khalida Mahi 2019)

Fig. 10- Blue Mosque, 1465, Tabriz (© Khalida Mahi 2019)

E YL Ü L - S E PT E M O B E R 2 0 2 2

31

�Fig. 11- Façade of the Blue Mosque, 1465, Tabriz (© Khalida Mahi 2019)

Fig. 12- Façade of the Çinili Köşk overlooking the Gülhane Park, 1472, Istanbul

(© Khalida Mahi 2019)

32

EY L ÜL - S EPTEM B ER 2022

�

Mehmet Tutuncu

Mehmet Tutuncu