לזכרו של פרופ פוירשטיין

לזכרו של פרופ פוירשטיין

Uploaded by

אמיר סטרנסCopyright:

Available Formats

לזכרו של פרופ פוירשטיין

לזכרו של פרופ פוירשטיין

Uploaded by

אמיר סטרנסCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

לזכרו של פרופ פוירשטיין

לזכרו של פרופ פוירשטיין

Uploaded by

אמיר סטרנסCopyright:

Available Formats

Never Say Never to Learning Dynamic

Cognitive Intervention (DCI) for persons with

Severe Mental Illness

NOAMI HADAS-LIDOR 1

PENINA WEISS 2

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to describe evidence-based research carried out

in populations related to the field of mental health, based on the theories

and work done by Prof. Reuven Feuerstein. These studies originated from

Hadas-Lidors Dynamic Cognitive Intervention (DCI) approach, which is derived from Feuersteins Structural Cognitive Modifiability theory. DCI is specifically intended for enhancement of therapeutic-based relationships with a

direct emphasis on emotional-related issues and the way they affect cognitive development.

One of the populations in which functional-cognitive abilities may be compromised is the population of people coping with mental disorders, due to effects of the illness and/or medication side effects.

The outlook for people diagnosed with mental illness has improved in the

past several decades due to reasons related to brain research development,

third generation medications and various psychosocial and cognitive treatments. These have allowed those coping with mental illness to achieve

meaningful recovery, manage residual symptoms, and lead productive lives.

Yet additional efforts are needed to consolidate these improvements and

help more people with mental illness to reach these goals.

Due to the negative effects of mental illness, positive communication skills

and abilities may be compromised, whether for those coping with mental illness themselves, or for those providing care for them either professionally or

as family members. In order to enhance learning and cognition, improve

communication and instill hope and meaning for all involved, the DCI approach provides a basis for various interventions related to mental health

that promote resilience, participation and recovery.

DCI incorporates use of Mediated Learning Experiences, exercises from Feuersteins Instrumental Enrichment program, and additional tools developed,

such as reading and writing tasks, utilization of personal picture albums and

Meaningful Interactional Life Episodes (MILEs). The studies reviewed in this

1. School of Occupational Health, Tel Aviv University. Address of correspondence:

noami.h@gmail.com;

2. Tel Aviv University

134 | NOAMI HADAS-LIDOR; PENINA WEISS

article include evidence for the benefits of DCI based interventions structured for those coping with mental illness, family, and professional caregivers.

Keywords

Feuerstein, Mental Health, Recovery, Caregivers, cognitive intervention

Introduction

Over the past fifty years the field of mental health care has greatly developed.

In the past, mental illness was often associated with neuro-cognitive degeneration and chronic deterioration of cognitive functions and abilities, with no

hope for rehabilitation and recovery. This usually was translated into a focus

on disability and weaknesses, social exclusion, lessened participation and a

lack of independence. For many years those suffering from mental illness did

not receive cognitive therapy, due to the belief that the cognitive impairment

was irreversible, together with the fact that cognitive intervention foundations were based on neuropsychology and therefore applied primarily for

people coping with brain injury (Green et al., 2000).

In recent years there are growing interactions between the fields of mental health and neuroscience research. Current trends in research on brain

plasticity, together with the exponential growth in new technology, show the

brain to be a far more plastic organ than previously thought (Doidge, 2007;

Kleim & Jones, 2008). After injury, the brain is capable of considerable reorganization that forms the basis for functional recovery (Sohlberg & Mateer,

2001). The fact that specific alterations in behaviour are reflected in characteristic functional changes in the brain is currently accepted by biologists

(Kandel, 1998, 2006). Thus, the ideas related to cognitive modifiability expressed by Feuerstein (Feuerstein et al., 1979; Feuerstein et al., 1980), pertaining to structural cognitive changes, are being found to be not just theoretical but are becoming scientifically validated (Hadas-Lidor et al., 2011).

Thanks to the developments in the field of brain research as it relates to

mental illness, together with advances in psycho-pharmacology, new attitudes and approaches that promote recovery, community integration and

rehabilitation are developing. These include psycho-education and psychosocial approaches and programs, cognitive interventions, psychiatric rehabil-

Never Say Never to Learning Dynamic Cognitive Intervention (DCI)... | 135

itation approaches and settings. These have brought about a huge change in

the quality of life of many people coping with severe mental health illness

(Lachman &Hadas-Lidor, 2003).

Concurrent with the changes in the mental health field, in the 80s' the

consumers of mental health services started the Recovery movement. The recovery movement has turned into the central approach to interventions in

mental health, primarily within the community (Friedli, 2010). In Recovery,

illness is viewed as a process and journey toward a satisfying and meaningful

life despite the illness, instead of regarding recovery as a cure (Anthony,

1993; Deegan, 1996; Liberman & Kopelowitz, 2005). Recovery places an emphasis on therapeutic relationships, demanding that providers collaborate

closely with each consumer to discover their unique path to healing (Tew et

al., 2011). Recovery is defined as a deeply, personal, unique process of changing one's attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills and roles. It is a way of living

a satisfying, hopeful and contributing life even with limitations caused by the

illness. Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in

one's life, as one goes beyond the catastrophic effects of mental illness (Anthony, 1993).

Feuerstein and the Recovery movement share common beliefs and concepts, such as the belief in a persons' ability to change, focusing on strengths

and not weaknesses, hope, the importance of experiencing competency. Hadas-Lidor, in the development of DCI combines these entities, both in theory

and practice.

There is a growing body of knowledge that provides evidence that cognition is a good predictor of functional rehabilitation outcomes in schizophrenia (Green et al., 2000). Cognitive interventions, whether in group or individual format, have become one of the central methods of intervention in this

population (Silverstein et al., 2001). The literature provides evidence to the

fact that cognitive interventions are beneficial for the population of the people with severe mental illness (Bellack et al., 2004; Hadas-Lidor et al., 2001;

Kandel, 1998; Kern et al., 2001; Silverstein et al., 2001; Spaulding, 1994).

One of the developments in the field of cognitive interventions in mental

health is based on the theories developed by Feuerstein (Feuerstein, Rand,

Hoffman, & Miller 1980; 2006).

Feuerstein (1980) formulated his theory of Structural Cognitive Modifiability (SCM), which presented the human being as an open system that can

be modified regardless of age and disability status. In general, Feuersteins

136 | NOAMI HADAS-LIDOR; PENINA WEISS

approach is concerned first with the cognitive prerequisites of human learning and problem-solving abilities; second, with examining why these abilities

fail to develop during early childhood in the absence of human mediation;

third, with focusing on systematic learning mediated by a caring adult; and

fourth, with how much later than generally thought possible, identified cognitive deficits can be remediated by a formal instructional program. This

formal program is based on a deductive style of training and teaching. Hadas-Lidor and her colleagues contributions' to the field of dynamic cognition

is in her approach being therapeutically based while including Recovery and

rehabilitative approaches, together with putting a direct emphasis on emotional-related issues and the way they affect cognitive development and

function. Her developing theory, over the past 20 years, Dynamic Cognitive

Intervention (DCI) evolved from her being an occupational therapist in the

field of mental health. Activity, participation and task analysis make up the

core of the Occupational therapy profession. Cognition is one of the abilities

both targeted as an outcome as well as a pathway to achieve participation in

everyday life activities and community integration. Following her exposure to

Feuersteins theories she applied this knowledge to structuring the Dynamic

Cognitive Intervention (Hadas-Lidor, Kozulin, & Weiss, 2011), primarily for

use in mental health but gradually expanding and applied with a broad range

of clients coping with various disabilities such as, learning disorders, ADHD,

acquired and traumatic brain injuries, dementia and old age, etc.

DCI emphasizes the human emotional experience in combination with

communication, cognition and activity in various life situations. Its purpose

is to enrich the learner and expand his range of coping and behavioural strategies. This expansion happens with the use of Feuerstein mediation principles that underwent renewed interpretation, to include and highlight the addressing of emotional aspects within everyday life interactions .For example,

Mediation of meaning is interpreted not just as in the meaning and understanding of things socially and culturally, rather, what is personally experienced as being meaningful, accentuating on what has meaning for me,

providing an emotional substance experienced by both learner and mediator. Mediation of Competence, is not just focusing on a feeling of ability, rather, it also includes strategies to build up feelings of ability, such as, provision of feedback, focusing on learning from successes, active listening and

more. Transference is not just linking a specific activity with others to promote the acquisition of principles or concepts. It is a tool used to actively en-

Never Say Never to Learning Dynamic Cognitive Intervention (DCI)... | 137

hance and bring into awareness meta- cognition by teaching the cognitive

principles and mediation components themselves in order to promote both

occupational and social skills.

In addition to Instrumental Enrichment, various intervention techniques

are activated, such as using family picture albums, reading and writing assignments, one of which is the Meaningful Interactional Life Episode (MILE).

MILEs are used in order to enhance learning and encourage the transfer of

knowledge and communication skills acquired during DCI individual or

group interventions, to participants natural environment. MILEs are real-life

documented verbal interactions experienced and submitted by those receiving DCI. The DCI expert analyses these MILEs and provides feedback to DCI

recipient regarding central components crucial to the development of learning and/or improved communications that are present or lacking within the

MILE (Weiss, 2013).

DCI principles

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

The intervention is structured in accordance with the consumers' choices and needs and not in relation to the diagnosis or the aetiology of the

illness.

Throughout the intervention there is a continuous process of discourse

between mediator and person receiving DCI regarding goals, purpose,

progression rate and the intervention methodology.

The DCI involves relating to various life aspects and roles- as long as the

Mediator uses Mediation within the verbal interaction taking place

throughout the intervention.

Meta-cognition is used, as DCI principles and intervention strategies are

shared and explained to person receiving the intervention, following the

belief, which professional tools of trade have to be shared as much as

possible with the person receiving the intervention (Knowledge Translation).

The entire intervention process is based on mediation, therefore, mediation is taught as a unique and separate methodology, to be applied in

every interaction. This entails specialized courses for the teaching of Mediation.

138 | NOAMI HADAS-LIDOR; PENINA WEISS

6.

All those involved with the person receiving the intervention are familiarized with Mediation strategies.

7. There is no definitive line drawn between assessment, intervention and

follow-up. They are intertwined throughout the entire process.

8. Highlighting, cognitive enquiry and analysis of experiences of success,

rather than focusing on difficulties and failures. This enables learning

from success and turns success into a model for replication.

9. Clearly defining between emotions, cognition and actions is used to help

understand the central role cognition plays within interactions, as well as

to enable improved cognitive self-control and improved understanding

of others participating in interaction.

10. Coexistence of Competence and Dysfunction- Focus on incorporation of

different characteristics that permanently reside side by side in each and

every one of us, in particular important for persons coping with mental

health illness.

DCI additionally expands Feuersteins approach in relevance to the environmental component. For years, Feuerstein related to the environment as

being dynamic and opposed segregation of persons with special needs. DCI

goes beyond this by focusing on the human component in the environmentparents, family, caregivers and professionals involved in caring for those with

special needs , under the assumption that it is not enough to improve the

persons self-ability to learn, but together with a change in the belief system of

the carer, in his/her ability to have faith in the person under care on a basis of

equality together with acquiring the ability to improve communications by

use of mediation techniques based on Mediated Learning Experience parameters- towards promoting Recovery-change, rehabilitation and integration.

There is a growing body of studies based on DCI principles. Those that focus

on populations of persons coping with mental illness; studies that focus on

family caregivers: and studies that focus on professionals. A number of these

studies are described below.

Never Say Never to Learning Dynamic Cognitive Intervention (DCI)... | 139

Research based on DCI in the mental health illness consumer

population

Hadas-Lidor, Katz, Tyano, and Weizman (2001) conducted the first study

based on SCM together with the above mentioned DCI principles in which

they investigated the effectiveness of cognitive dynamic treatment through

the use of IE with adults with mental illness. The participants included 60

consumers who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and required treatment at a rehabilitation day centre. The consumers were randomly assigned

into two groups; one was given IE as the intervention, and the control group

received traditional intervention, which included participation in newspaper

groups, arts and crafts. In the study group only certain exercises were used,

specifically those that relate to rehabilitation and recovery, such as, employment integration, making choices, social skill development, etc. The length

and scheduling of the intervention were equal for both groups. The study had

a prepost quasi-experimental design and lasted for 6 months. The following

variables were measured before and after intervention: cognitive performance, self-concept, and daily functioning. The results after intervention

showed significant differences between the study group and the control

group in the areas of cognitive performance and daily functioning, in both

home and work environments. No significant differences were found regarding self-concept. The findings' of this study, which was the first to examine

the effectiveness of IE on adults with schizophrenia, had important implications. It suggests not only that the IE program is effective but also that consumers with schizophrenia can improve their cognitive skills and everyday

functioning.

A follow-up study to this study was performed by Speier-Keisar, HadasLidor, &Lachman (2007).Individuals with psychiatric disorders are often excluded and discriminated against in society (Ralph, 2000). This study examined the efficacy of Dynamic-Cognitive Intervention and its influence on

cognitive and social functioning of people coping with schizophrenia who reside in the community.

The study was conducted in a community rehabilitation centre. The sample included 28 subjects with schizophrenia, whose age ranged from 23-37

year, who were divided into two matched groups. All of the participants were

assessed before and after the intervention. The experimental group received

18 weekly dynamic-cognitive interventions of one hour. The control group

140 | NOAMI HADAS-LIDOR; PENINA WEISS

participated in the centres regular activities which included provision of

support, psychotherapy, illness treatment management, and workshops or

employment units. A significant improvement was noted for the study group

subjects on social F (3, 24) = 18.52, P< .001; cognitive F (3, 24) = 8.17, p<.001

and occupational measures (significant improvement progression of occupational status in study group as compared to controls) as compared to the

control group subjects after six months. The results of this study support

short-term dynamic-cognitive intervention for individuals with schizophrenia in the community.

In a third study, a comparison of performance of the static version (including an additional exposure) and the dynamic version of the Rey Osterrieth Complex Figure test (ROCF) was carried out. The ROCF is used to assess

cognitive functions such as visual-spatial organization, sequencing and

memory. Cognitive dynamic assessments of people recovering from mental

illness can provide a deeper understanding of learning propensity, and therefore contribute to improving recovery and rehabilitation, whilst developing a

feeling of competence and motivation to change. The additional exposure to

the figure on the static version of the test was chosen since some of the criticism of dynamic testing methodology, claims that the exposure in itself is the

source for improved performance of the copying and memory of the figure

during the second part of the dynamic version of the test. The study also examined feelings of competence as experienced by participants' in both

groups. The study population was a group of consumers using social club

community mental health services (Nachmany-Asher, &Shefa, Hadas-Lidor,

2013). The study included 60 subjects between the ages 23-69. The participants were divided into two groups: in the first group, the static form of the

test was administered (including an additional stage of exposure), so it consisted of five stages (1- copying, 2- drawing from memory, 3-exposure to the

complex figure without mediation for three minutes, 4- copying and 5- drawing from memory); In the second group, the dynamic form of the test was

administered, in accordance with the instructions described in the Learning

Propensity Assessment Device (LPAD) manual. In this group, all the subjects

received second level mediation that included verbal analysis of the components of the complex figure. In addition, subjects of both groups were asked

an open-ended question about their feeling of competence at the end of the

test. Amongst subjects who underwent the dynamic form of the test significantly higher results were found in comparison to those who underwent the

Never Say Never to Learning Dynamic Cognitive Intervention (DCI)... | 141

static form on second copying, second drawing from memory, the rate of

change and the grading of competence at the end of the test. The researchers

conclude that the dynamic form of the ROCF provides a more in-depth understanding of learning propensity and subject's competence. Increasing use

of the dynamic form could guide occupational therapists and other professionals in constructing a better tailored intervention plan for consumers, increase their feeling of competence, encourage them to continue in their efforts and activities and therefore promote their rehabilitation.

Research based on DCI with the population of family caregivers

Family caregivers have been defined as the most important human resource

for home-based long-term care (World Health Organization, 2000). Keshet, is

an instructional and educational course given in academic settings for those

caring for their familys mentally ill members, since 2001. The Keshet course

aims at enhancing positivistic family cognitive communication skills in everyday life interactions. It is based on Feuersteins theory of Structural Cognitive Modifiability (Feuerstein, Rand, & Feuerstein, 2006) and the Dynamic

Cognitive Intervention principles of Hadas-Lidor and Weiss (Hadas-Lidor,

Weiss, &Kozulin, 2011). Meaningful Interactional Life Episodes (MILEs) are

used in order to enhance learning and encourage the transfer of knowledge

and communication skills acquired within the course framework, to participants natural environment. These are real-life documented verbal interactions experienced and submitted by participants. Keshet moderators analysed these MILEs and provided feedback to participants regarding these

MILEs as they relate to course content.

The goal of the course is to train parents and caregivers awareness in the

use of cognition; to better understand the behaviour of their mentally ill child

and to react to him/ her in a controlled and structured manner, in order to

influence his/ her responses via their interactions with him. Furthermore, the

participants are encouraged to use mediation in their interactions with medical and rehabilitation services personnel.

In an initial study following the first 3 Keshet groups, a pilot study was

carried out with a group of 11 participants. They completed an attitude questionnaire relating to beliefs, self-knowledge and actions in relation to their

children, before and after the course. Participants reported a higher level of

142 | NOAMI HADAS-LIDOR; PENINA WEISS

knowledge, beliefs and changes in their actions that they interpreted as positive, following the Kismet course (Hadas-Lidor, Hasdai, &Jarus, 2006). These

results were replicated in additional groups of Keshet (Weiss, 2013).

An initial study that evaluated Keshet was performed by Shor (2009).

Eighty eight Keshet participants participated in this evaluation. The objective

of the evaluation was to evaluate the contribution of the course and the

changes they experienced during and after the course, as a result of their

learning the DCI approach. The methodology was based on multiple single

subject designs, and the implementation of quantitative and qualitative

methods. The findings indicate that the Keshet program changed the participants perception of their life incidents with which they are coping and of the

resources available to them in coping with these incidents.

A study conducted by Redlich, Hadas-Lidor, Weiss, and Amirav (2009) examined whether the Keshet program effectively increases family members

hope for themselves versus hope for their ill relative. The experimental group

was composed of 49 family members who participated in the Keshet program

for 6 months, in contrast to the control group, which comprised 22 family

members, who underwent no structural intervention. Hope was measured at

baseline and after 6 months using the Hope Scale, developed by Snyder

(1998). No difference in self-perception was detected in Hope Scale scores

between groups; however, the Keshet program significantly increased the

hope of families concerning the ill person while decreasing the gap between

the hope of family members regarding themselves and the affected person.

Thus, the program may increase the families feeling of hope during the journey toward recovery of family members with mental illness.

Keshet was also the platform for the examination of cultural differences in

the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community. (Weiss, Hadas-Lidor, Shor, 2013)The

influence of the familial context of people with mental illness has come to be

recognized as being significant to the course of mental illness; however, the

role of culture in the manifestations of the dynamics within families of persons with mental illness has been an unexplored subject. A study (Weiss, Hadas-Lidor & Shor, 2013) was performed of 24 ultra-orthodox Jewish mothers

of persons with mental illness, who live in a relatively closed religious community in Israel. As part of their participation, the members of two groups of

the Kismet educational program designated for family caregivers of persons

with mental illness were asked to write meaningful interactional life episodes

(MILEs), which focused on stressful events in their lives. Qualitative analysis

Never Say Never to Learning Dynamic Cognitive Intervention (DCI)... | 143

of 50 MILEs illuminated the significant role that religious and cultural norms

had in the perceptions of what the participants considered stressors and the

dynamic in the families in regard to these stressors. Four themes were identified: (a) conflicts between religious rituals and the disability; (b) stressors that

stem from the need to maintain the secrecy of familial events in a collectivist

society; (c) stressors that stem from time-related events, such as holidays;

and (d) mothers as a major bearer of the burden of caregiving. The authors

emphasized the importance of relating to cultural factors in family educational programs and interventions, because this may contribute to the potential use and success of mental health services within a population that essentially underutilizes these services. Accruing this knowledge is essential if

therapists want to adapt the methods of interventions in educational programs, such as Keshet, to the needs of parents living in a closed religious collectivist society. The MILEs could also be applied as a means of developing

culturally oriented techniques with other cultural populations and members

of racial/ethnic minority groups that underutilize mental health services because of cultural barriers. In the work of Feuerstein, there is an emphasis on

the adaptations needed for minority populations, such as immigrants from

countries such as Ethiopia and North Africa, stating that we should not regard them as people who lack intelligence, rather as people who are culturally different (Feuerstein, &Richel, 1963).

A comprehensive effectiveness study of Keshet was conducted by Weiss

(2014).

Study objectives were (a) to develop an instrument for structured analysis

of the MILEs (b) to examine the effectiveness of the Keshet course for family

caregiver wellbeing and (c) to develop a "Knowledge Translation" based

model of cognitive educational intervention for family members of persons

coping with mental disorders based on an occupational therapy domain perspective relating to communication and recovery.

Methodology: The first section of this study includes the development of

a tool for the analysis of MILES, the Meaningful Interactional Life Episodes

Evaluation Tool (MILEET). Keshet moderators were the designated population for the tool development study. Their written responses to MILEs were

compared and analysed pre/post use of this newly developed tool.

As Keshet is a complex health intervention, the intervention effectiveness

section of this study utilized a mixed methodology approach. Quantitative

questionnaires relating to family attitudes, problem solving, communication

144 | NOAMI HADAS-LIDOR; PENINA WEISS

skills, goal attainment, burden and quality of life, were used for this study.

The design is quasi-experimental, using the same group of people at different

stages. Thirty-eight participants filled out study evaluation questionnaires at

three different times: at least three months prior to course attendance, at initiation and at completion of the course. This created a control condition

(waiting list) and a study condition (pre-post course attendance). Finally, focus groups of graduating Keshet participants were held in order to provide a

qualitative perspective.

Findings

The MILEET development resulted in the structuring of a reliable tool for

MILE analysis, yet the use of the MILEET did not evoke a significant improvement in MILE analysis for experienced Keshet moderators. Regarding

the effectiveness outcome study, following Keshet participation, and as compared with the study control condition, quantitative findings pointed to significant changes in participants attitudes regarding knowledge of how to

cope with a mentally ill family member. Participants also reported a significant improvement with regard to objective and subjective burden. Participants and moderators identified a significant positive change in the ability of

participants to cope with the MILEs. Qualitative data analysis revealed three

central themes (1) Keshet is an attempt to go beyond the despair and frustration to improved relationships with self, child and the health system; (2)

Keshet is a means to improve communication empowerment and feelings of

competency and (3)The group leaders meaningful role and effect on learning and promoting recovery and change.

Conclusions

Keshet aids family caregivers in mental health in the development of skills

and attitudes that improve cognitive communication skills and in turn, improves resilience in the caregiving role. This is accomplished with the use of

the MILEs that provide meaningful links between theoretical components

taught and the participants actual experiences. Caregiver resilience is identified as being a meaningful outcome which to date has not received sufficient

attention. The MILEET, developed within the framework of this study, is a re-

Never Say Never to Learning Dynamic Cognitive Intervention (DCI)... | 145

liable tool, apparently primarily useful for novice moderators. For the population of family caregivers in mental health, Keshet is an intervention model

that promotes Knowledge Translation that may positively affect public health

and promotion.

Policy implications and recommendations

Inclusion of Keshet as an evidence based intervention for family caregivers in

mental health within designated family centres operating in Israel under the

Rehabilitation of the Mentally Disabled in the Community Law (2000) is recommended. Further research on the use of MILEs as a tool for the development of communication patterns based on cognition and mediation and a

longitudinal study focused on the resilience of caregivers as it relates to participation in Keshet are warranted.

Research based on DCI with professionals

For the past ten years, specialized programs in the study of DCI intended for

professionals are given in academic institutes in Israel. In preparation for the

development of these studies, a group of therapists participated in a workshop aimed at developing teaching and mediation skills. The training in the

workshop itself, was based on application of the dynamic cognitive approach. The study evaluated attitudes held by the participants toward teaching roles before and after the workshop. On the basis of both qualitative and

quantitative analyses, it appears that the workshop facilitated changes in participants attitudes toward teaching, on emotional, cognitive, and practical

levels.

The questionnaire is composed of two sections, one quantitative and the

other an open ended qualitative question.

The questions on the questionnaire were organized randomly and divided

into three groups, three questions per topic: knowledge and emotions related

to teaching, and questions relating to feelings of competence regarding

teaching.

Eighteen participants filled out attitude questionnaires at initiation and

termination of the program.

146 | NOAMI HADAS-LIDOR; PENINA WEISS

A t test analysis of the participants' responses to the questionnaire revealed significant differences in attitudes regarding knowledge, emotions, and teaching competence. The combined score for all three sub

scales showed an average score at termination as being significantly higher

than at initiation. These findings point to significant changes in beliefs, emotions, and behaviours in relation to participants' roles as dynamic cognitive

therapists and to their belief in their clients ability to change and develop as

a result of the therapeutic intervention and interaction. In the qualitative section of the study, participants identified strengths and weaknesses in their

teaching skills, and conveyed how the workshop had improved their skills as

teachers and instructors (Hadas-Lidor, Naveh, & Weiss, 2006)

An additional study assessed the actual effects of the academic study programs in DCI for professionals. Program participants come from diverse

health-related professions and the program enabled the development of

common grounds for communication and intervention principles which

were enhanced while maintaining unique professional identity is maintained. Efficacy of the program was assessed by giving attitude questionnaires to participants before and after conclusion of the program. These

point to significant changes in beliefs, emotions, and behaviours in relation

to participants' roles as dynamic cognitive therapists and to their belief in

their clients ability to change and develop as a result of the therapeutic intervention and interaction (Hadas-Lidor, & Weiss, 2007).

Conclusions

Prof. Reuven Feuersteins work and the theories he developed have reached

and are being applied far and beyond the populations he started out working

with. One of these populations, as described in this paper are those coping

with mental health illness. DCI is based on the SCM and MLE theories, together with elements from the recovery vision, an emphasis on emotions and

cognition and meta-cognition as implemented in the profession of occupational therapy. We believe that the DCI principles which integrate these

components can advance people on their Recovery journey.

This paper reviewed studies based on DCI in populations related to the

field of mental health. Three studies were conducted within the population of

persons coping with mental health illness, five studies involved families of

Never Say Never to Learning Dynamic Cognitive Intervention (DCI)... | 147

persons coping with mental illness and two studies were carried out with

professionals who provide mental health services.

These studies point to the effectiveness of Dynamic Cognitive Intervention, its' importance for consumers, caregivers and professionals in the field

of mental health, and the broad spectrum with whom this intervention may

be applied. DCI does not focus on illness and illness management. It is rather based on a universal outlook on cognitive modifiability and the use of

mediation for positive communication applications. Regarding the Keshet

intervention for family caregiver's that is based on DCI, it is clear that the

mental health family caregivers needs should be addressed since homebased care is an integral component of all health and social systems. Keshet

is held within settings that are identified within a health and not an illness

perspective (academic setting vs. hospital/clinic). Within this context it is

important to initiate such interventions and encourage family caregivers to

participate in these interventions from the early stages of their coping with

family mental illness. The population of caregivers should be encouraged

and reinforced in their need for support, caring for themselves, and acquiring

practical strategies for improved caring and coping. Public health care providers and program instigators should be made aware of the importance of

these crucial needs.

Additional studies on the use of DCI as a basis for identifying communication patterns and the establishing of effective cognitive communication in

various populations of persons with special needs are warranted.

When Prof' Reuven Feuerstein was asked whether cognitive interventions

would make people happier, he answered "Happiness is in Gods' hands. My

role is to expand people's possibilities and ability to make choices".

148 | NOAMI HADAS-LIDOR; PENINA WEISS

References

Anthony, W.A. (1993). Recovery from mental health illness: The guiding vision of

the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychological Rehabilitation

Journal, 16, 1124.

Bellack, A.S., Mueser, K.T., Gingerich, S., & Agresta, J. (2004).Social skills Training

for Schizophrenia. NY London: The Guilford Press.

Deegan, P.E. (1996). Recovery as a journey of the heart. Psychiatric Rehabilitation

Journal, 19(3), 91-97

Doidge, N. (2007). The brain that changes itself. Penguin: London.

Feuerstein, R., with Rand, Y., Hoffman, M. B., & Miller, R. (1980). Instrumental enrichment: An intervention program for cognitive modifiability. Baltimore: University Park Press.

Feuerstein, R.,withRand, Y., & Hoffman, M. B. (1979) The dynamic assessment of

retarded performers: The Learning Potential Assessment Device, theory, instruments, and techniques. Baltimore: University Park Press.

Feuerstein, R. &Richel, M. (1963).Children of the Malach: Cultural depravation of

Moroccan children and its meaning for Education. The Jewish Agency, Henrietta Sold Institute, Jerusalem.

Feurstein, R., Rand, Y., &Feurstein, R.S. (2006).You love me!!...Dont accept me as I

am. Revised and enlarged edition. Jerusalem: InternationalCenter for Enhancement of Learning Potential Publications.

Green, M.F., Kern, R.S., Braff, D.L. &Mintz, J. (2000). Neurocognitive Deficits and

Functional Outcome in Schizophrenia: Are We Measuring the Right Stuff?

Schizophrenia Bulletin, 26, 119136.

Hadas-Lidor, N., Katz, N., Tiano, S., Weizman, A.(2001) Effectiveness of Dynamic

Cognitive Intervention in Rehabilitation of Clients with Schizophrenia. Clinical Rehabilitation: 15 (4), August 2001.349-359

Hadas-Lidor, N., & Weiss, P. (2007), An academic diploma program as a lever for

personal and professional growth and empowerment. The Israel Journal Of

Occupational Therapy, 16,3, E61-E74.

Never Say Never to Learning Dynamic Cognitive Intervention (DCI)... | 149

Hadas-Lidor, N., Naveh, E. & Weiss, P. (2006). From Therapist to Teacher: Development of Professional Identity and the Issue of Mediation. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 6,1, 100-116.

Hadas Lidor, N., Hasdai, A., Jarus, T., "KESHET" advancement participation and

communication course for parents and caregivers for cognitive communication Israel Journal of Occupational Therapy: 15 (1) February 2006, 31-46,

(Heb.)

Hadas-Lidor, N., Weiss, P. & Kozulin, A. (2011). Dynamic Cognitive Intervention:

Application in Occupational Therapy. In N. Katz (Ed.) Cognition, Occupation,

and Participation Across the Life Span (pp.323350). Bethesda, MD: AOTA.

Kleim, J., & Jones, T. (2008). Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity:

Implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51 225-239.

Liberman, R.P., &Kopelowitz, A. (2005). Recovery from Schizophrenia: A concept

in search of research. Psychiatric Services, 56, 735742.

Rehabilitation of the Mentally Disabled in the Community Law, 2000 . Jerusalem,

Ministry

of

Justice,

2000.

Available

at

www.old.health.gov.il/Download/pages/lawENG040409_2.pdf

Silverstein SM1, Menditto AA, Stuve P. (2001) Shaping attention span: an operant

conditioning procedure to improve neurocognition and functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin.;27(2):247-57.

World Health Organization. (2000). Home-based long-term care: Report of a WHO

study group.(Technical report series 898).Geneva: Author. Retrieved May 4,

20011, from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/WHO_TRS_898.pdf

Tew, J., Ramon, S., Slade, M., Bird, V., Melton, J., & Le Boutillier, C. (2011). Social

factors and recovery from mental health difficulties: A review of the evidence.

British Journal of Social Work [June]118

Friedli, L. (2010). Proceedings of the 2010 Refocus on Recovery conference, Institute

of

Psychiatry,

London.

Retrieved

http://www.researchintorecovery.com/conference/materials.html

1-2-11

from

accessed

150 | NOAMI HADAS-LIDOR; PENINA WEISS

Kern, R. S., Wallace, C. J., Hellman, S. G.,Womack, L. M & Green, M.F. (1996). A

training procedure for remediating WCST deficits in chronic psychotic patients: an adaption of errorless learning principles. Journal of Psychiatric Research,30, 283-294

Medalia, A., Revheim, N., &Casey, M. (2001). The remediation of problem solving

skills in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 27, 259-267.

Kandel, E. R. (1998). A new intellectual framework for psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 457469.

Ralph, R.O. (2000). "Recovery". Psychiatric Rehabilitation skills, 4(3), 480-517.

Spaulding W.D.(1994) (Eds) Cognitive technology in psychiatric rehabilitation.

University of Nebraska press.

Shani Shefa, Orit Nahmani Asher, NoamiHadasLidor (2013). Comparison between Static and Dynamic Forms of the Rey Osterrieth Complex Figure Test

(ROCF) and Their Impact on the Self-Efficacy of People with Mental Illness in

the Community. The Israeli Journal of Occupation Therapy, November 2013,

22(4) 85-103

Sohlberg, M. M., & Mateer, C. A. (2001). Cognitive rehabilitation: An integrative

neuropsychological approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Redlich, D., Hadas-Lidor, N., Weiss, P., &Amirav, I. (2009) Mediated Learning Experience Intervention Increases Hope of Family Members Coping with a Relative with Severe Mental Illness. Community Mental health Journal. DOI

10.1007/s10597-009-9234-3,

Shor, R. (2009). The Keshet program-Advancement, participation and communication. The Israeli National Insurance Institute, Research and Planning Administration, Division for Service Development, Special report No. 130, Jerusalem.

Speier-Keisar V. , Hadas-Lidor N., Lachman, M. (2007) The Efficacy of DynamicCognitive and Social Functioning of Persons with Schizophrenia in the community, The Israeli Journal of Occupation Therapy, vol 16 (1) p (3-27),

Weiss,P., Hadas-Lidor, N., &Shor, R.(2013). Cultural aspects within caregiver interactions of ultraorthodox Jewish women and their family members with

mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83' 520-527

Never Say Never to Learning Dynamic Cognitive Intervention (DCI)... | 151

Weiss P. (2013). Keshet-A Cognitive Educational Intervention Model for Family

Caregivers of Persons Coping with Mental Disorders: Providing Evidence for Effectiveness. University of Haifa, Unpublished manuscript.

You might also like

- A Module in Forensic 2Document88 pagesA Module in Forensic 2Cristian Joshua C. SalibongcogonNo ratings yet

- Performance Task in Statistics and ProbabilityDocument4 pagesPerformance Task in Statistics and ProbabilityAnn Gutlay100% (3)

- Introduction To PsychoeducationDocument9 pagesIntroduction To PsychoeducationAneeh100% (1)

- Poster On Lifespan DevelopmentDocument1 pagePoster On Lifespan DevelopmentAntor ShahaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Pender's Health Promotion Model: Context and Content of The TheoryDocument9 pagesAnalysis of Pender's Health Promotion Model: Context and Content of The TheoryAsih Siti SundariNo ratings yet

- Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society, Second EditionDocument3 pagesGovernmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society, Second EditionavriqueNo ratings yet

- Dci 2011Document28 pagesDci 2011אמיר סטרנס100% (2)

- PDF 74145 81369Document5 pagesPDF 74145 81369Joel AmetllerNo ratings yet

- SAKELLARI Et Al-2011-Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health NursingDocument11 pagesSAKELLARI Et Al-2011-Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursingandreia_afonso_30No ratings yet

- Classwork 3 UNIT 6 Compare & Contrast Essay PART 2Document4 pagesClasswork 3 UNIT 6 Compare & Contrast Essay PART 2Genesis OrellanaNo ratings yet

- PsychoeducationDocument9 pagesPsychoeducationSrinivas Pandeshwar100% (1)

- Personhood of Counsellor in CounsellingDocument9 pagesPersonhood of Counsellor in CounsellingPrerna singhNo ratings yet

- Are Coping Strategies, Emotional Abilities, and Resilience Predictors of Well-Being? Comparison of Linear and Non-Linear MethodologiesDocument13 pagesAre Coping Strategies, Emotional Abilities, and Resilience Predictors of Well-Being? Comparison of Linear and Non-Linear MethodologiesBrittany Caroline BlackNo ratings yet

- SIL ATTITUDE TOWARDS MENTAL HEALTHDocument11 pagesSIL ATTITUDE TOWARDS MENTAL HEALTHvandana28012007No ratings yet

- Vandevelde Morisse Et Al IJDD 2014 - SED-R-with-cover-page-v2Document14 pagesVandevelde Morisse Et Al IJDD 2014 - SED-R-with-cover-page-v2Martina GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Status of Student Leaders: Basis For An Enhancement ProgramDocument10 pagesMental Health Status of Student Leaders: Basis For An Enhancement ProgramPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Module-I Introduction & Historical Overview StructureDocument9 pagesModule-I Introduction & Historical Overview StructureAmeena FairozeNo ratings yet

- HLTH 499 Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesHLTH 499 Literature Reviewapi-583311992No ratings yet

- Mental Health and Coping Strategies of Private Secondary School Teachers in The New Normal: Basis For A Psycho-Social Wellbeing Developmental ProgramDocument18 pagesMental Health and Coping Strategies of Private Secondary School Teachers in The New Normal: Basis For A Psycho-Social Wellbeing Developmental ProgramPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Mental HealthDocument11 pagesMental Healthmahmoodosman91No ratings yet

- Metacognitive Reflection and Insight Therapy (Lysakker)Document11 pagesMetacognitive Reflection and Insight Therapy (Lysakker)Cesar BermudezNo ratings yet

- Lesson planDocument25 pagesLesson planNaz Naz BaclidNo ratings yet

- 2021 Sustained, Multifaceted Improvements in Mental Well-Being Following Psychedelic ExperiencesDocument17 pages2021 Sustained, Multifaceted Improvements in Mental Well-Being Following Psychedelic ExperiencesMariana CastañoNo ratings yet

- RRLDocument4 pagesRRLMark CornejoNo ratings yet

- Document_0004-3Document12 pagesDocument_0004-3Bassam AlqadasiNo ratings yet

- LR Meo 2014-2Document10 pagesLR Meo 2014-2api-260733603No ratings yet

- Strengths Against Psychopathology in Adolescents: Ratifying The Robust Bu Emotional IntelligenceDocument13 pagesStrengths Against Psychopathology in Adolescents: Ratifying The Robust Bu Emotional IntelligenceJose Antonio Piqueras RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document7 pagesChapter 1magtulismikeyvanNo ratings yet

- research-nga-gi-edit-ni-may-ann-karong-december-3-2024Document37 pagesresearch-nga-gi-edit-ni-may-ann-karong-december-3-2024elgen.alarcon01No ratings yet

- Spiritual Intelligence and Well-Being of Caregivers of Neurodevelopmental DisordersDocument10 pagesSpiritual Intelligence and Well-Being of Caregivers of Neurodevelopmental DisordersMarbe HmtNo ratings yet

- 02bfe50d98359a7de3000000 PDFDocument6 pages02bfe50d98359a7de3000000 PDFomkarenatorNo ratings yet

- Ijsret v10 Issue6 558Document5 pagesIjsret v10 Issue6 558Pramit DasNo ratings yet

- Mental Health ContohDocument5 pagesMental Health Contohalicia heraNo ratings yet

- ADHD Meditation 2015Document33 pagesADHD Meditation 2015Marlene LírioNo ratings yet

- 9p - Intellectual Disability and Mental Health - Is Psychology PreparedDocument9 pages9p - Intellectual Disability and Mental Health - Is Psychology Preparedtiagompeixoto.psiNo ratings yet

- Psychology - Selected PapersDocument342 pagesPsychology - Selected Papersrisc0s100% (2)

- Salud Mental Versus Enfermedad Mental: Una Perspectiva de Educación para La SaludDocument4 pagesSalud Mental Versus Enfermedad Mental: Una Perspectiva de Educación para La SaludJuan Rocha DurandNo ratings yet

- An Integrative Approach To Psychotherapy With Special Emphasis On Homeopathic Model.Document12 pagesAn Integrative Approach To Psychotherapy With Special Emphasis On Homeopathic Model.Homoeopathic PulseNo ratings yet

- A Salutogenic Mental Health Model Flourishing As ADocument13 pagesA Salutogenic Mental Health Model Flourishing As AAna EclipseNo ratings yet

- RESEARCHDocument3 pagesRESEARCHOlalia, Sophia Angela M.No ratings yet

- MH 02 PDFDocument11 pagesMH 02 PDFAllain BartolomeNo ratings yet

- Isa BongamDocument5 pagesIsa BongamPhil PendaNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 18 01387Document15 pagesIjerph 18 01387David QatamadzeNo ratings yet

- A Study of A Social-Emotional Learning Program For College Students Integrating MindfulnessDocument7 pagesA Study of A Social-Emotional Learning Program For College Students Integrating MindfulnessAlika Setia PutriNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Mental Health LiteracyDocument23 pagesIntroduction To Mental Health LiteracyWinter sozinyoNo ratings yet

- Essay On Branches of Psychology - Ipshita BagchiDocument11 pagesEssay On Branches of Psychology - Ipshita Bagchiipshita bagchiNo ratings yet

- A Pilot Trial of Mindfulness Meditation Training For AttentionDeficit Hyperactivity Disorder in AdulthoodDocument26 pagesA Pilot Trial of Mindfulness Meditation Training For AttentionDeficit Hyperactivity Disorder in AdulthoodParla CardoNo ratings yet

- Minduflness Entrenamiento Richard DavidsonDocument10 pagesMinduflness Entrenamiento Richard DavidsonElizabethNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Mental Health NursingDocument8 pagesDissertation Mental Health NursingHelpWritingPapersUK100% (2)

- The Model For Sustainable Mental Health Future DirDocument10 pagesThe Model For Sustainable Mental Health Future Dirjmielcarek1No ratings yet

- Learning To BREATHE A Pilot Trial of A MindfulnessDocument12 pagesLearning To BREATHE A Pilot Trial of A Mindfulnessyujiachen2395No ratings yet

- Training in mental health promotionDocument37 pagesTraining in mental health promotionAkhil ChandranNo ratings yet

- Teaching Empathy Through Movies: Reaching Learners' Affective Domain in Medical EducationDocument13 pagesTeaching Empathy Through Movies: Reaching Learners' Affective Domain in Medical EducationSorina NataliaNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Art and Music On Cognitive Function and Mental Health Well Being pr1Document7 pagesThe Influence of Art and Music On Cognitive Function and Mental Health Well Being pr1Patricia CayabyabNo ratings yet

- Psychosocial Interventions DraftDocument12 pagesPsychosocial Interventions DraftDwane PaulsonNo ratings yet

- 1-Article_Text-61-1-10-20210202Document12 pages1-Article_Text-61-1-10-20210202Alvian Rizqi AndrianaNo ratings yet

- Lifespan DevelopemntDocument10 pagesLifespan DevelopemntAntor ShahaNo ratings yet

- Group Intervention For Youth Depression and Anxiety: Outcomes of A Randomized Trial With Adolescents in KenyaDocument33 pagesGroup Intervention For Youth Depression and Anxiety: Outcomes of A Randomized Trial With Adolescents in KenyaTom OsbornNo ratings yet

- Does Mindfulness Meditation Increase EmpathyDocument20 pagesDoes Mindfulness Meditation Increase EmpathyzaezelzsNo ratings yet

- Transpersonal ASSDocument6 pagesTranspersonal ASSheaven shadreckNo ratings yet

- Conferencia Dr. CondonDocument5 pagesConferencia Dr. CondonAlexa Yakeline MenesesNo ratings yet

- Mind Magic: Building a Foundation for Emotional Well-BeingFrom EverandMind Magic: Building a Foundation for Emotional Well-BeingNo ratings yet

- Rapid Core Healing Pathways to Growth and Emotional Healing: Using the Unique Dual Approach of Family Constellations and Emotional Mind Integration for Personal and Systemic Health.From EverandRapid Core Healing Pathways to Growth and Emotional Healing: Using the Unique Dual Approach of Family Constellations and Emotional Mind Integration for Personal and Systemic Health.No ratings yet

- Naomi CV - English, Updated Lan 2018Document24 pagesNaomi CV - English, Updated Lan 2018אמיר סטרנסNo ratings yet

- Naomi CV - English, Updated Lan 2018Document24 pagesNaomi CV - English, Updated Lan 2018אמיר סטרנסNo ratings yet

- 11 TSJPSpecIssueFeuerstein2014 - Noami Hadas Lidor - 219 220Document2 pages11 TSJPSpecIssueFeuerstein2014 - Noami Hadas Lidor - 219 220אמיר סטרנסNo ratings yet

- לזכרו של פרופ פוירשטייןDocument19 pagesלזכרו של פרופ פוירשטייןאמיר סטרנסNo ratings yet

- Dominos SowDocument17 pagesDominos SowSuprotaNo ratings yet

- Guidance On Good Manufacturing PracticeDocument153 pagesGuidance On Good Manufacturing PracticeOanh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Analysis of Online and Traditional Class To The Academic Performance of Selected University StudentsDocument13 pagesA Comparative Analysis of Online and Traditional Class To The Academic Performance of Selected University StudentsasdasdaNo ratings yet

- English4 Q1 DLP Week6 PrefixesDocument4 pagesEnglish4 Q1 DLP Week6 PrefixesTGie OczNo ratings yet

- Admission Into Full and Part Time Postgraduate Programmes For The 20202021 Academic Session - 1601403975Document63 pagesAdmission Into Full and Part Time Postgraduate Programmes For The 20202021 Academic Session - 1601403975dunmiju victoryNo ratings yet

- GSP WeekDocument9 pagesGSP WeekANALYN LANDICHONo ratings yet

- ACI Structural JournalDocument10 pagesACI Structural JournalAbdifatah HassanNo ratings yet

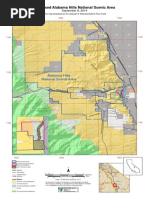

- Alabama Hills Legislation MapDocument1 pageAlabama Hills Legislation MapRep. Paul CookNo ratings yet

- LO 4: Clean Up On Completion of Cropping Work According To Company Standard ProceduresDocument37 pagesLO 4: Clean Up On Completion of Cropping Work According To Company Standard ProceduresRizaLeighFigues100% (2)

- Mandibular Canine IndexDocument5 pagesMandibular Canine Indexyordin deontaNo ratings yet

- AP Chemistry The Origin of Flame ColorsDocument2 pagesAP Chemistry The Origin of Flame ColorsNWong 63604No ratings yet

- Worksheet ADocument3 pagesWorksheet AM Riel Cim AlbancesNo ratings yet

- Bayesian Updating: Probabilistic Prediction Class 12, 18.05 Jeremy Orloff and Jonathan BloomDocument4 pagesBayesian Updating: Probabilistic Prediction Class 12, 18.05 Jeremy Orloff and Jonathan BloomMd CassimNo ratings yet

- The Six Major Subfields of LinguisticsDocument2 pagesThe Six Major Subfields of LinguisticsNoelia NoeliaNo ratings yet

- GAAP Updated Profile 2022Document10 pagesGAAP Updated Profile 2022Som BoyNo ratings yet

- The Tendency of Hotel Rooms Division Managers To Create BudgetaryDocument14 pagesThe Tendency of Hotel Rooms Division Managers To Create BudgetarySolomon ZewduNo ratings yet

- Rilsan Fine Powders Physical PropertiesDocument2 pagesRilsan Fine Powders Physical Propertiesธนาชัย เต็งจิรธนาภาNo ratings yet

- ITMProposers Day2022020v6Document32 pagesITMProposers Day2022020v6熊俊捷No ratings yet

- Tutorial Sheet OneDocument3 pagesTutorial Sheet Onemesho posoNo ratings yet

- HANA Consistency CheckTableConsistency Results 1.00.100+Document8 pagesHANA Consistency CheckTableConsistency Results 1.00.100+Rafael Gonzalez HernándezNo ratings yet

- Additional Mock CAT VARC Test 3Document28 pagesAdditional Mock CAT VARC Test 3mayank palNo ratings yet

- Quantity Surveyor Job in Canterbury Naver Love - SEEKDocument4 pagesQuantity Surveyor Job in Canterbury Naver Love - SEEKKanil RanaweeraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14 15e Lecture Slide HandoutDocument6 pagesChapter 14 15e Lecture Slide HandoutSamuel Owusu DonkoNo ratings yet

- Algorithms and FlowchartsDocument4 pagesAlgorithms and FlowchartsgeetharjunforeverNo ratings yet

- Depositional Environments Lec. 10 Carbonate Platforms: Dr. Ehab M. Assal Damietta UniversityDocument37 pagesDepositional Environments Lec. 10 Carbonate Platforms: Dr. Ehab M. Assal Damietta UniversityAbram Louies HannaNo ratings yet

- Writing Assessment Criteria: CEFR B2Document3 pagesWriting Assessment Criteria: CEFR B2Cambridge EmpowerNo ratings yet

- ESAF Small Finance BankDocument1 pageESAF Small Finance BankVishwajit GoudNo ratings yet