Dispoyrous Eboneum Tree

Dispoyrous Eboneum Tree

Uploaded by

Mani VannanCopyright:

Available Formats

Dispoyrous Eboneum Tree

Dispoyrous Eboneum Tree

Uploaded by

Mani VannanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Dispoyrous Eboneum Tree

Dispoyrous Eboneum Tree

Uploaded by

Mani VannanCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/322782682

Diospyros ebenum

Chapter · January 2018

DOI: 10.1002/9783527678518.ehg2015001

CITATIONS READS

0 7,850

2 authors:

Joachim Schmerbeck Niyati Naudiyal

Freelance consultant 24 PUBLICATIONS 105 CITATIONS

36 PUBLICATIONS 259 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Acacia auriculiformis View project

Ecosystem functions and services in Delhi: Regeneration under the canopy of Prosopis juliflora View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Niyati Naudiyal on 14 May 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Diospyros ebenum

III-4

Diospyros ebenum J. KOENIG EX RETZ., PHYSIOGR.

SÄLSK. HANDL. 1: 176 (1781)

syn.: Diospyros ebenaster Retz., Observ. Bot. 5: 31 (1788), Diospyros glaberrima

Rottler, Nye Saml. Kongel. Vidensk. Danske Selsk. Skr. 2: 539 (1783), Diospyros

melanoxylon Willd., Sp. Pl. 4: 1109 (1806), nom. illeg., Diospyros membranacea

A.DC. in A.P. de Candolle, Prodr. 8: 227 (1844), Diospyros reticulata var. timori-

ana A.DC., Prodr. 8: 225 (1844). Diospyros laurifolia A. Rich. in R. de la Sagra,

Hist. Fis. Cuba, Bot. 11: 86 (1850), Diospyros timoriana (A.DC.) Miq., Fl. Ned.

Ind. 2: 1045 (1859), Diospyros assimilis Bedd., Rep. Forest. Madr.: 20 (1866) [25]

Ebony Family: Ebenaceae

Span.: El ébano

French: Ébène

German: Ebenholz

Hindi: Kendhu

Tamil: Karunkaali,

Solaikarimaram,

Thumaraam,

Velleithuvarai,

Vellathovarai

Telugu: Tuki

Sinhala: Kaluwara

Figure 1: Diospyros ebenum. Vigorous young tree in

the Angamedille National Park Sri Lanka.

Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse – 69. Erg. Lfg. 01/17 1

Diospyros ebenum

III-4

High-quality wood has always been in demand in human [35] observed the species in the Kurrukpoor Hills near

societies. It is loved and used extensively by those who Munger, which today is the Munger District (Bihar), and

can afford it. In Egypt, ebony was most likely used as ear- Singh [36] states that the species occurs in Kerala and

ly as 4500 years B.P. [11], and later, the Roman Empire even in Assam and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

also developed a high demand for ebony wood. Much One of the most astonishing features of the species is the

of this demand was satisfied by the Indian Diospyros wide range of annual precipitation that it is found ranging

species [41]. The two ebony species mainly traded from from 750 mm [34] to more than 7000 mm [2]. The spe-

India were D. melanoxylon and D. ebenum. However, cies has been observed near Agumbe, Karnataka, where

the latter is the “only one giving a black wood without the annual precipitation is as high as 7000 mm [14]. This

other streaks or markings …” [13]. The wood was first prompts the question of what limits the species from

brought to Rome around 2000 years ago [41] and was distributing across an even wider area. One explanation

traded with rulers of the Europe during the Renaissance. could be the change in rainfall pattern, e.g., from a dis-

Around 400 years ago, the term “ebenist” was used for symmetric to a tropical rainfall regime, which occurs when

the finest carpenters of France [9]. For millennia, ebony moving from the south of India to the north. This change

has been harvested in India so that by the time of the is reported by Meher-Homji [27] as being the limitation

British arrival a large percentage of the ebony was al- for the extension of the dry evergreen forest communities

ready cut, mostly by using very destructive methods [37]. of which D. ebenum is a part. However, this climatic pat-

Because of this, not much of the species was left on the tern driving the distribution can be doubted as both re-

subcontinent [13], and the still plentiful stocks in Sri Lan- gimes occur in the area where the species is distributed. In

ka (then Ceylon) were the main source for the British of this context, it has to be recalled that the species has been

this much-in-demand wood. Some of these stocks remain exploited for thousands of years and that anthropogenetic

today, even though they were heavily exploited. pressure can be expected to have a stronger influence than

Despite the high value of the species and the potential that climatic or edaphic factors. A previous, larger range of the

the species promises with scientific management, it does species is therefore likely.

not receive much attention from the scientific world. The There are some indications of D. ebenum occurrence out-

species is classified as endangered in Sri Lanka [21] and side of India: Prinz [32] states that it occurs in the jungle

its trade is banned in both India and Sri Lanka. However, of Nigeria, but the probability is high that the identifi-

in the course of the forest ecosystem restoration work in cation is not correct, as many Diospyros species exist in

South India, the species is used and distributed. Africa. However, its occurrence in gardens is likely, as

reported by Delchevalerie [10] from gardens in Egypt.

The word “Diospyros” is of Greek origin: dios meaning

Distribution and Forest History “divine” and pyros meaning “fire” or “burned”, which

would make the meaining of “divine fire”. Such a mean-

The natural and present-day distribution of the species is ing cannot be explained by the author. Dahms [9] states

in South India and Sri Lanka [26]. In Sri Lanka, Broun that pyros means “corn/grain” and the word “Diospyros”

[6] observed the species in forests all over the island. Al- would therefore mean “divine food”, but evidence for

though it was most abundant in dry forests, it also ap- such a translation could not be found. The name “eb-

peared in moist forests in the south of the island. A de- ony” seems to have its root in the Egyptian word hbny

tailed description of the species in Sri Lanka today is not [11]. This entered the Greek language where the word

known to the authors. ebenos was used for the dark woods that came from

The species distribution in India can be outlined more India or Egypt [9]. From the 17th century onwards, the

clearly based on several studies made in South India. word was adopted by European languages (e.g., French

The species can potentially occur in all forest types in ébène, Spanish ebano, German Ebenholz). Most likely,

the plains of Tamil Nadu and southern Karnataka as the deepest incorporation of the word ebony in a Eu-

well as in the Eastern Ghats and the eastern slopes of the ropean language took place in France where the word

Western Ghats. Beddome [3], Brandis [5] and Gamble “ébéniste” means carpenters who make very fine furni-

[13] report the presence of the species in Andhra Pradesh ture (cabinet makers) [9]. According to the same author,

(mainly in the Cuddapah and Karnool Districts where the old Egyptian name also influenced the development

the tree, according to Beddome [3], “is very common of the scientific name, which was first given in 1737 by

and well known”), and Haines [17] described the species the botanist N. L. Burgmann as “Ebenus Burm.”. In

to occur even further north in the Champagarh forest, 1778, Johann Gerhard Koenig, a Danish botanist

which today is the Similipal National Park (Khurda dis- who worked with Linnaeus, sent a letter from Tranque-

trict), as well as in the Angul district (Orissa). Sherwill bar (India) to Prof. Rottboel, who was the “chief of

2 Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse – 69. Erg. Lfg. 01/17

Diospyros ebenum

III-4

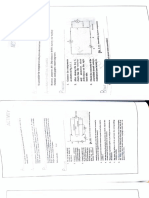

Figure 2: Distribution of Diospyros ebenum according to records found by the authors. The natural distribution is likely to

cover a much wider area.

botany in the Chair of Medicine in Copenhagen”, stating states that it was “most improbable that ebony should

that he recently completed a journey to Ceylon where he have been obtained from India or Ceylon at such an early

discovered the true ebony [19]. The establishment of the period …” and places a trade of “such material” at the

actual scientific name by Koenig is described in detail by earliest in the 18th dynasty (around 1500 B.C.). Dixon

Howard and Norlindh [20] who also described how [11], however, doubts this statement as trade between In-

the name “Diospyros ebenaster” appeared as a synonym dia and Egypt with precious stones existed as early as this

for D. ebenum, which created a lot of confusion for de- piece of ebony wood was dated. However, evidence in

cades to follow. The publication that first gave the spe- the form of finished objects of ebony wood from Egypt is

cies the name Diospyros ebenum was in an article writ- only available from the middle of the 18th dynasty [11].

ten by Koenig [19] in Swedish with the title “Diospyros Another important trade of ebony wood occurred between

Ebenum eller Äkta Ebenholz, beskrifvit af John Gerhard India and Rome [4, 37, 41]. According to Warmington

König” (Diospyros ebenum or true ebony, described by [41], since the time of Pompey (around 80 B.C.), Rome

John Gerhard Koenig) published in 1781 in the first received ebony wood from India through the Persian Gulf

volume of the Lund Physiographiska Sälskapets Handl- where it was brought by Indian merchants and traded by

ingar. As Koenig’s article was translated and edited by Arabians. The wood was used mainly for furniture and

A. J. Retzius, the founder and secretary of this journal, statuary. As the Roman Empire extended to large parts

the correct name of the species is Diospyros ebenum of Europe, it is likely that products made out of ebony

Koenig ex Retzius [19]. wood reached Europe already at the beginning of the

The earliest recorded trade of Indian ebony wood seems first millennium after Christ. However, records about the

to have taken place with Egypt. According to Dixon [11] trade of ebony wood within the Roman Empire are not

a piece of wood from the fifth dynasty (as early as 2400 known to the authors of this monograph. According to

B.C.) was identified as Diospyros ebenum, which could Boomgaard [4], the trade with the remaining Western

only have originated from India or Sri Lanka. Lucas [11] world and Asia started between 500 and 1500 AD.

Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse – 69. Erg. Lfg. 01/17 3

Diospyros ebenum

III-4

According to Dahms [9], ebony wood came to Germany

in the 14th and 15th century via Venice on the old Bren-

ner trading route. Later the wood was shipped through

Lisbon (Portugal) and afterwards was traded through

Antwerp (Netherlands), from where it was distributed

along the Rhine and the North Sea coast. By this time,

German carpenters had already specialised in the man-

ufacture of valuable ebony cabinets, which were traded

with the royal court of Spain [9]. From the 16th and 17th

century onwards, ebony was often included in furniture

construction and was in demand by those strata of soci-

ety that could afford it. Ludwig XIV. (1638–1715) sent

for German carpenters who went as “Ebenisten” to Paris

in the 17th century to make furniture in the Royal Fur-

niture Factory founded by Ludwig XIV. in 1667 [9]. This

Figure 3: Flower buds. Left: Female flower; right: male

time apparently represents the peak of the world’s ebony flower.

trade, because from that time onwards it declined tre-

mendously. Ebony was predominantly used during this

time as an inlay and for ornamental pieces. The invention

of the veneer-cutting technique (at the beginning of the

19th century [21]) allowed for entire furniture fronts to

be made of ebony as well as wooden planks out of ebony

wood [9]. This indicates that a sufficient stock must have

been available to European manufactures, which might

have been the result of stockpiling by wood traders or

wood manufactures. According to Boomgaard [4], by

the 18th century, there was no longer any ebony wood

imported by Holland from anywhere in the world, and

the author supposed that the Indian stock had nearly

dried up by then. It is therefore very likely that, when the

British came to power in India, there was not much ebo-

ny left to exploit. Literature from the early 20th century

by Brandis [5], Troup [39] and Gamble [13] mentions

that the specimens of ebony found in India were not of Figure 4: Male flower abloom.

considerable size. However, at this time, a much better

supply of the species existed in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon)

and the urgent need for sustainably managing what re-

mained of the resource was emphasized by Gamble.

Today, the trade of ebony wood from India and Sri Lanka

is banned [22] and the species is Red Listed, at least for

Sri Lanka [21]. Nonetheless, in India, the tree can still be

found, small in size, at many locations and is used locally

to make handles for small tools [34].

Morphology

Appearance and Habit

D. ebenum is a large tree. According to Broun it can

reach a girth of 14 feet (equivalent to 1.37 m in diameter)

[6]. Reliable height measurements are not available, but a

maximum height of 30 m is recorded in the literature [28]. Figure 5: Underside of a leaf, young fruits with dried flowers.

4 Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse – 69. Erg. Lfg. 01/17

Diospyros ebenum

III-4

The tree is in general densely foliated and the crown is

dark green and compact. It is evergreen, which means

that it will never be without leaves as long as it is alive. If

the tree grows in the shade or in close proximity to oth-

er trees, the crown usually makes up from 1/3 to 1/2 of

the entire tree length, but the proportion of crown length

can be even greater in individuals not constrained by

growth-limiting factors. It habitually has a straight single

trunk, but it can also have multiple stems, without be-

ing the result of coppicing. The tree can produce coppice

growth after cutting, especially when at a young age.

Buds

Flowers and shoot buds are found in the leaf axils. Buds

Figure 6: Foliage on a young tree.

of the male flowers are clustered in short cymes. Howard

and Norlindh [19] observed densely pubescent young

buds and less pubescent older buds on the specimens col-

lected by Koenig during his trips to Ceylon; however, no

flora guide known to the author makes this observation.

Leaves

The leaves are alternate, oblong to elliptic, 6–10 cm long

and 3–5 cm broad, thinly coriaceous, glabrous with a

rounded to acute base. The apex is (sub)acute to obtuse

and the veins are minutely reticulate, raised and conspic-

uous on both surfaces, while the mid-vein is clearly visi-

ble. The petiole is up to 0.5 cm long [5, 26]. Fresh leaves

are bright green and shiny.

Young Shoots

Young light-green shoots arise from the axillary buds and

have fine soft hairs on the surface at the earliest stage of

development [5].

Figure 7: Fruits in diverse stages of development. Top: Un-

Flowers ripe green fruits; bottom: ripe green-brown fruits.

The species is dioecious.

Male flowers: 3–16 flowers appear as short axillary cymes,

the peduncle is up to 0.5 cm long and the pedicles reach

a length of up to 3 mm. The calyx is cupular, 3.5 × 3 mm,

glabrous and the 4 lobes are obscure, ciliate, and obtuse.

The corolla is tubular to salver formed, up to 1 cm across

and up to 7 mm long; the 4 lobes are ovate-oblong, 6 mm

long and acute. The flowers have 6–12 stamens in uneven

groups while the filaments are 1.5–3.5 mm in length and

the anthers are linear and up to 4 mm long; the connetives

are crested and apiculate; the pistillode is linear and up to Figure 8: Cut open fruit with visible seeds lying within.

2 mm long [26]. Right: Dried seeds.

Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse – 69. Erg. Lfg. 01/17 5

Diospyros ebenum

III-4

Female flowers arise from the leaf axils but are solitary

with a pedicle up to 3 mm long. The calyx has 4 lobes,

which are 4 mm long, ovate, shortly united, (sub)acute

and spreading. The corolla is cream coloured, tubular,

3 mm across with a tube of 6 mm long and 4 acute lobes,

each 6 mm. The ovary is glabose, 4.5 × 4 mm with 4

styles and capitellate stigmas; 6–12 staminodes [26].

Fruits

The fruits are globose berries with a short, apical break,

measuring 1.5–2 cm across. The calyx forms a shallow

wooden cup and is reflexed [5, 26]. Each fruit contains

3–6 seeds. When old, the fruit dries and turns grey.

Seeds

The seeds are black, 10–13 mm long and 2–5 mm wide

at the back, tapering at the front to 0–1 mm. According

to Orwa et al. [28], 1 kg of seed contains around 9000

seeds, while Jean Pouyet [31] counted 5000 seeds/kg.

Wood

A clear distinction can be observed between the sapwood

and heartwood of the species, although the relative pro-

portions of both vary greatly. The proportion of heart-

wood in the trunk declines with increasing soil quality

[6]. The trunks of individuals growing on deep soil have Figure 9: Bark of a larger tree in the Angamedille National

Park Sri Lanka.

14–35 % heartwood while data for rocky soil are not

available. The light coloured, soft sapwood is not of

much use. D. ebenum is the only species that produces

entirely black heartwood, but the process of pigmenta-

tion is slow and irregular. Howard and Norlindh men-

tion that, during his visit, Koenig was shown by a local

forester how the status of pigmentation was checked by

drilling through the sapwood into the heartwood [6, 20].

The heartwood, if fully pigmented, is absolutely dark

(jet black) and produces very fine sawdust. According to

Broun, dried wood has a weight of 1.2–1.4 t/m3 [6]. Dahms

[9] provides the same figures for his general description

of wood properties for black wood-producing Diospyros

species. As a detailed description of other wood properties

for D. ebenum could not be found by the authors of this

monograph, Dahms description is used here. The black

heartwood can show a deep blue tone and the pores are

often filled fully with black pigments, which makes them

almost invisible on the surface. The orientation of the fi-

bres is irregular. Figures for the chemical composition of

the wood are available only for Diospyros celebica, which Figure 10: Deadwood of Diospyros ebenum. Angamedille

National Park Sri Lanka.

has 41 % pure cellulose, 48 % lignin and 17 % pentose.

6 Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse – 69. Erg. Lfg. 01/17

Diospyros ebenum

III-4

The wood is generally chemically inactive, except in the

case of a polyester varnish which is inhibited by the pig-

ments and has a propensity for discoloration due to wood

extracts. The wood has a strong tendency to contract, es-

pecially in bigger pieces where it can also develop cracks.

The tangential shear is 12.8 % and the radial shear 8.2–

10 %. The compression strength lies somewhere between

53 and 78 N/mm2, the bending strength lies between 100

and 164 N/mm2 and the elasticity modulus at 12,000–

15,000 N/mm2. The wood is resistant to weathering and

highly resistant to fungal attack. However, tiny wood-bor-

ing insects (larvae) can cause damage to the wood. Defects

in the wood can appear as bending, hollowness and heart

rot, and sawn wood can break at thin spots. Veneer can Figure 11: Cut wood with wood dust.

show grey areas, spots or bands.

The sawdust can be injurious to health, especially the

Table 1 Taxonomic classification of Diospyros ebenum (based on

eyes and respiratory organs. [12, 16]).

Bark Order Diospyrales

Family Ebenaceae

The young bark is smooth, green to dark grey, some-

Subfamiliy Ebenoideae

times almost black. It tends to darken with age and crack

longitudinally. These cracks lead to a rough longitudi- Genus Diospyros

nal structure with rectangular pieces in a younger stage Species Diospyros ebenum J. Keonig ex Retz.,

of the tree development and scales at a more advanced Physiogr. Sälsk. Handl. 1: 176 (1781)

stage, which fall off eventually.

a single genus: Lissocarpa. The genus Diospyros is widely

Rooting Habit distributed in the tropics and subtropics. According to

Duangjai et al. [12], approximately 300 species occur in

Seedlings of D. ebenum have a very long taproot, which Asia and in the Pacific areas, 98 species in Madagascar

often tears while transplanting seedlings. Large pots/ and the Comoros, 94 species in the mainland of Africa,

plastic bags have to be used for raising the seedlings as around 100 species in the Americas, 15 species in Austra-

the roots easily penetrate through the plastic bags into lia and 31 species in New Caledonia.

the soil. Care has to be taken that the seedlings are shif- The four genera of the family Ebenaceae are monophy-

ted in time, to avoid damage to the seedling while ta- lous while the genus Diospyros is closely related to the

king the pots out of the seedling bed as the root often African genera Euclea and Royena [16]. However, the

grows deep into the soil. The available literature does authors state that the “current distribution patterns in

not provide any information on the rooting habit of ma- Diospyros can be explained by dispersal only with no

ture trees, but it can be assumed that the trees develop a vicariance events”, which, according to the authors, in-

deep taproot. dicates that the genus has a capacity for long-distance

dispersal. Singh [36] describes 66 species of Diospyros in

India, of which 50 % have originated in India.

Taxonomy, Genetic

Studies on the genetic differentiation with the species of

Differentiation, Races and D. ebenum do not exit. Whether the wide range of phe-

Hybrids notypic variation of the growth form is based on geno-

typic variations is therefore unknown.

D. ebenum belongs to the family Ebenaceae [26], sub- No subspecies and races of D. ebenum have been re-

family Ebenoidae [16] (Table 1). This subfamily contains ported, although the occurrence of this species in areas

around 600 species distributed amongst three genera (Di- with vast differences in the amount of precipitation as

ospyros, Euclea, Royena) [16], of which Diospyros is the described above makes the existence of subspecies likely.

largest with more than 500 species [12]. The family of There is also no evidence that the species hybridises with

Ebenaceae has another subfamiliy, Lissocarpoideae, with other species or is part of any breeding program.

Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse – 69. Erg. Lfg. 01/17 7

Diospyros ebenum

III-4

Growth, Development and Yield Reproduction and Regeneration,

In contrast to the importance of the species for trade and Propagation, Cultivation

its high-value timber, very little knowledge exists regard-

ing its growth rates and yield. The most comprehensive D. ebenum is reproduced via seeds. The best results are

work is that of Broun [6]. According to the author, the achieved by sowing 2–3 seeds directly in big pots. As

species can reach a circumference of 14 feet, which is seedlings develop a root that can be up to 10 times longer

equivalent to a diameter of 1.37 m (the author does not than the above-ground parts, large pots have to be used

indicate at which position on the trunk this measurement and shifted every 6 months to avoid damage to the roots

was taken). Pointing to the need to correct his figures, which would otherwise grow too deep into the soil [31].

which are based on only a few observations, he states that After 3 years in pots, the trees can be planted in the field.

the growth slows down after the tree has reached a girth Shade must be provided during the time the trees spend

of 3 feet (equal to 0.92 m, equates to 0.29 m in diameter). in the nursery and in the first years after planting. Lack

Broun provides the growth rates given in Table 2. of shade can be partially compensated for by irrigation.

Table 2 Growth rates of Diospyros ebenum, according to [6, 39]. In full sunlight, the species can reach maturity on fer-

tile soil under irrigated conditions by the age of 6 years,

Age (years) Girth Diameter (m) but the seeds produced are not very viable (own obser-

inches m vation). Regeneration in the wild can be abundant, often

occurring directly under the mother tree. The species can

25 18 0.46 0.15

also disperse for some distance (own observation), but

75 36 0.91 0.30

the distance and vectors are not known. It can be ex-

135 54 1.37 0.44 pected that, under suboptimum conditions, the species

200 72 1.83 0.58 needs more time to produce viable seeds, but even so,

this would still be at a relatively young age. Broun [6]

mentioned that the yield of seeds varies from year to

Data concerning height growth are not available. Irriga-

year, mainly determined by the amount of rainfall during

tion enhances the growth rate of seedlings by approxi-

the monsoon, but he could not observe a regular pattern

mately 5–7 times, an effect that can be expected to reduce

of distinct seed years.

with age.

There are no reports about any current cultivation of the

Data on the annual yield of ebony wood are not avail-

species, besides Chriat [8] who mentions that the tree

able; however, to get at an idea of the amount of wood

was cultivated in the French colonies, and the World Con-

that was harvested, we again have to go back to Broun

servation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) mentions that the

[6]. In the years between 1862 and 1881, 22522.5 t

tree is cultivated in Malaysia [42]. The only silvicultu-

of ebony (on average 1126 t/a) was exported from Sri

ral instructions available are those given by Broun [6]

Lanka, excluding local use, which was, according to the

based on the cultivation of the species in Sri Lanka in the

author, of significant volume. The year 1881 marks the

19th century. The seedlings require a shady environment

peak in export volumes of ebony from Sri Lanka, with

to establish and should be provided with slightly more

approximately 2600 t. In 1888, the export was only

light at later stages of development. Broun [6] states that

617 t, and in the period from 1889 to 1898, the exported

branches located right above established saplings should

amount was reduced to 300 t/a.

be removed. However, full light and space should not be

Today, the black and coloured wood of Diospyros spe- provided until the tree reaches its full size. Broun expects

cies is still traded. The logs are relatively small and sold that the tree, in that stage, will still be vital enough to

in kilogram amounts [9]. However, larger quantities are enlarge its crown after trees in close proximity to it are

currently for sale on the internet, with prices up to USD removed [6, 30].

5000/t [1].

However, silvicultural measures have never been seriously

applied to D. ebenum. Stebbing [37] states that the wood

harvesting methods used in India before the British came

to power were very destructive. A good picture of the

wasteful “management practices” of the valuable ebony

is provided by Broun [6]: “But the damage done to the

forests was by no means confined to the amount of ebony

8 Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse – 69. Erg. Lfg. 01/17

Diospyros ebenum

III-4

Figure 13: Regenration of Diospyros ebenum under a

monther tree in the Pachamalai RF, Tamil Nadu.

Photograph: Richi Walker.

fellers did not want to waste their time on trees giving a

small yield of blackwood. They therefore went from tree

to tree, not even sparing comparatively small ones, and

with their axes cut deep notches on different sides so as

to find out how deep the heart-wood lay. In some forests,

especially in those within fairly easy reach of the sea, there

is hardly a tree to be found which is not thus mutilated.

The marks thus made almost invariably lead to unsound-

ness and it is pitiable to find in forests, which have been

worked many years back, hardly any but hollow trees.”

Ecology

D. ebenum is part of the Tropical Dry Evergreen For-

est of South India and Sri Lanka [6, 7], but it has been

also observed in the Tropical Moist Forests of South In-

dia [14] and Sri Lanka [6]. The tree is fairly resistant to

drought. However, it is distributed over a wide range of

annual precipitation from 750 mm [34] up to 7000 mm

[14]. It is found at elevations ranging from sea level [29]

up to 1000 m [26]. Broun and all authors after him re-

port that the species is most often found on rocky, well-

Figure 12: D. ebenum, young plant about 2 years old. drained, sandy loam soils with good subsoil drainage. It

Photograph: Rishi Walker can also be found on clayey soil, but not commonly. It is

never found in swampy areas, although it often occurs

near places where water runs seasonally.

exported. First of all the felling were made without any

consideration for silvicultural requirements. Then, there The species exhibits many features of a late succession-

is a very fair local trade in ebony, which is not taken into al tree species, such as having shade-tolerant seedlings, a

consideration in the table of exports. A lot of trees were seedling bank, being slow growing, producing valuable

also wasted, felled and found hollow and too far to be timber and having a long life span. In contrast to this, it

carted at a highly remunerative rate and they were left in also has traits more common of early successional spe-

the forests to rot … Perhaps the greatest harm done to the cies, such as the capability to produce seeds at an early

ebony forests was caused by tapping the trees. As I have age and the ability to coppice. It can be assumed that the

said before, the amount of heart-wood varies greatly. The species has evolved in an environment prone to regular

Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse – 69. Erg. Lfg. 01/17 9

Diospyros ebenum

III-4

disturbances like storms, cyclones or impacts by large cording to Broun [6], the wood was used in China to

animals like elephants. However, the species can be ex- manufacture chopsticks and carved stands for support-

pected to be a significant part of the climax vegetation ing vases, cabinet work and many other small items. The

in dry forest areas [24]. The tree can certainly not stand most famous uses for the wood might be for ornaments,

the impact of fire and has also not been observed in areas fine furniture, veneer and parquet floors. There is almost

where frost occurs. no information available about its use by local forest

dwellers in India and Sri Lanka, but it seems that local

While the mode of seed dispersal remains unclear, the

forest dwellers know about the species and use it to some

abundant regeneration below mother trees indicates

extent. Beddome [3] states that the sapwood is used by

that most of the seeds do not get dispersed far. Broun

the local people for “various purposes”. Schmerbeck

guessed that surface water plays an important role in

[34] records that local people near Bathlagundu in Tamil

the distribution of the species but contradicts himself by

Nadu, South India, use the wood of young trees to make

stating that specimens of the species are found at remote

knife handles. As these trees are utilized even when their

places upstream from the mother tree’s location [6]. The

diameters are very small, it is unlikely that they have de-

same observation was made by the author in a degrad-

veloped any heartwood.

ed tropical dry forest in South India. Broun hold birds

and mammals responsible for the dispersal [6] while Many products claimed to be of ebony were actually imi-

observations in Auroville (South India) show that bats tations. Heath [18] points out that the word “ebenized”

and civet cats disperse the fruits [31, 33]. Accepting that was used for the “thousand and one articles of furniture

long-range dispersal of the genus Diospyros is a proven and articles of ornaments” that were coloured to pass as

fact [16] and considering the strong human impact on true ebony.

forest ecosystems in the native range of the species over

Due to its dense foliage D. ebenum produces valuable

the last millennia, the possibility that important vector

shade throughout the year and even under drought con-

species have been strongly reduced or are even extinct

ditions, but it is not often used for this purpose.

cannot be excluded.

There are a few indications that it is also being used

for other purposes: Broun refers to literature from the

Pathology “Ceylon forester” which suggests that shavings of ebony

wood mixed with other species can be used as a remedy

for toothaches and ebony sawdust mixed with sulphur

Pathogens or diseases that affect the species to an extent

was used “in dog’s food as a remedy for mange”. Ja-

that its performance is reduced are not known for either

yaraman [23] states that the species is also used for gum

seedlings or adult trees. However, Stebbing [38] men-

and the fruits are used for food and medicine. In addi-

tions a beetle (Coccotrypes integer) that causes damage

tion, the WCMS describes that the fruits are used as fish

to the seeds while they are in the fruit, and Paucot [30]

poison [42].

states that a Putnam scale insect (Aspidiotus ancylus (Di-

aspidiotus ancylus)) lives on the plant. Jean Pouyet [31]

stated that the leaves of mature trees can show chlorosis

of some kind which does not affect the tree. Literature

[1] Alibaba.com, 2014: Search results for “ebony timber”.

Uses [2]

http://www.alibaba.com/showroom/ebony-timber.html.

ARRS (Agumbe Rainforest Research Station), 2014:

http://www.agumberainforest.com/fast_facts.html.

The main use of the species is for its wood. The jet black [3] Beddome, R. H., 1869: The Flora Sylvatica for Southern

wood is easy to polish and is primarily used for turn- India. Adelphi Press, Madras.

ing, small ornamental inlay and as veneer. Dahms [9] [4] Boomgaard, P. (1998): The VOC trade in forest prod-

lists many small items that are made out of ebony wood, ucts in the seventeenth century. In: Grove, H. R.; Da-

like ornaments, carved figures, cutlery handles, moulded modaran, V.; Sangwan, S. (eds.): Nature and the Orient,

The Environmental History of South and Southeast Asia.

recesses, gaming pieces, door handles, brushes, combs,

Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 375–395.

and billiard cues. In addition ebony is used in the mak- [5] Brandis, D., 1906: Indian Trees. First Commemorative.

ing of musical instruments like piano keys, fingerboards, Natraj Publishers, Dehradun.

drum sticks, xylophones, and for wind instruments like [6] Broun, A. F., 1899: Ceylon Ebony. Diospyros ebenum

recorders, bag pipe pipes, bassoons and clarinets. Ac- Koenig. Indian Forester 25.

10 Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse – 69. Erg. Lfg. 01/17

Diospyros ebenum

III-4

Figure 14b: Diospyros ebenum at the same location and of

the same age. The trees are standing open and

are regularly irrigated.

[9] Dahms, K. G., 1990: Das Holzportrait: Ebenholz. Eur. J.

Wood Wood Prod. 48, 385–389.

[10] Delchevalerie, G., 1884: Curiosités horticoles de

l’Égypte. L’Illustration Hortic 4, 81.

[11] Dixon, D. M., 1961: The ebony trade of ancient Egypt.

Doctoral thesis. University of London.

[12] Duangjai, S.; Samuel, R.; Munzinger, J.; Forest, F.;

Wallnöfer, B.; Barfuss, M. H. J., Fischer, G.; Chase,

M. W., 2009: A multi-locus plastid phylogenetic analysis

of the pantropical genus Diospyros (Ebenaceae), with an

emphasis on the radiation and biogeographic origins of

the New Caledonian endemic species. Mol. Phylogenet.

Evol. 52, 602–620.

[13] Gamble, J. S., 1922: A Manual of Indian Timbers. Bishen

Singh Mahendra Pal Singh Publisher, New Delhi.

[14] Ganeshaiah, K. N., unpublished: Indian Bio-resource

Information Network (IBIN), funded by the Department

of Biotechnology, Government of India. School of Ecolo-

gy and Conservation, UAS, Bangalore.

[15] Ganeshaiah, K. N., unpublished: National Programmes

on Mapping Plant Resources of Western Ghats and East-

ern Ghats, funded by the Department of Biotechnology,

Government of India. School of Ecology and Conserva-

tion, UAS, Bangalore.

[16] Geeraerts, A.; Raeymaekers, J. A. M.; Vinckier, S.;

Pletsers, A.; Smets, E.; Huysmans, S., 2009: System-

atic palynology in Ebenaceae with focus on Ebenoideae:

Figure 14a: D. ebenum in the understory of a tree planta- Morphological diversity and character evolution. Rev.

tion near Bodinayakkanur, Teni District Tamil Palaeobot. Palynol. 153, 336–353.

Nadu, South India. The tree is 20 years old and

received very little irrigation. [17] Haines, H. H., 1922: Botany of Bihar and Orissa, Part

IV Gampoetalae. Adlard and Son and West Newman

Ltd., London.

[7] Champion, H. G.; Seth, S. K., 1968: A Revised Survey [18] Heath, R. A., 1886: Sylvan Winter. Kegan Paul Trench

of the Forest Types of India. Government of India Press, & Co., London.

Delhi. [19] Howard, R. A.; Norlindh, T., 1962: The typification

[8] Chirat, L., 1855: Étude des fleurs – Botanique élémen- of Diospyros ebenum and Diospyros ebenaster. J. Arnold

taire, descriptive et usuelle. Vol. 3, Lyon, Girard et Josser- Arbor. 43, 94–107.

and. [20] Howard, R. A., 1961: The correct names for “Diospyros

ebenaster”. J. Arnold Arbor. 42, 430–433.

Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse – 69. Erg. Lfg. 01/17 11

Diospyros ebenum

III-4

[27] Meher-Homji, V. M., 2001: Bioclimatology and Plant

Geopgraphy of Peninsular India. Scientifc Publishers,

Jodhpur.

[28] Orwa, C.; Mutua, A.; Jamnadass, R.; Anthony, S.;

2009: Agroforestree Database: A tree reference and se-

lection guide version 4.0. http://www.worldagroforestry.

org/output/agroforestree-database [Zugriff: 29.11.2017].

[29] Parthasarathy, N.; Karthikeyan, R., 1997: Plant bio-

diversity inventory and conservation of two tropical dry

evergreen forests on the Coromandel coast, South India.

Biodivers. Conserv. 6, 1068–1083.

[30] Paucot, M. R., 1907: Sur quelques Diaspinées des serres

du Muséum. Bulletin du Muséum national d'histoire na-

turelle, France.

[31] Pouyet, J., 2014: Personal communication.

[32] Prinz, E., 1908: Die Bau- und Nutzhölzer. Verlag Bern-

hard Friedrich Voigt, Leipzig.

[33] Rollet, P., 2014: Personal communication.

[34] Schmerbeck, J., 2003: Patterns of Forest Use and Its In-

fluence on Degraded Dry Forests: A Case Study in Tamil

Nadu, South India. Shaker Verlag, Aachen.

[35] Sherwill, S. R., 1852: The Kurrukpoor Hills. J. Asiat.

Soc. Bengal 21, 195–206.

[36] Singh, V., 2005: Monograph on Indian Diospyros L.

(Persimmon, Ebony), Ebenaceae. Botanical Survey of In-

dia, Government of India.

[37] Stebbing, E. P., 1922: The Forests of India. John Lane

The Bodley Head Ltd., London.

[38] Stebbing, E. P., 1914: Indian Forest Insects of Economic

Figure 15: Diospyros ebenum coppice growing with a Importance – Coleoptera. Eyre & Spottiswoode, London.

Comiphora caudata tree on a ridge top in the [39] Troup, R. S., 1921: Silviculture of Indian Trees. Interna-

Kadavakurich Reserved Forest, Dindigul Dis-

tional Book Distributors, Dehradun.

trict, Tamil Nadu, South India. Age of the tree

is unknown but it is expected that it was cut [40] Walker, R., 2014: Personal communication.

several times. [41] Warmington, E. H., 1928: The commerce between the

Roman Empire and India. 2nd edn., Vikas Publishing

House, Delhi.

[21] IUCN (International Union for Conservation of [42] WCMC (World Conservation Monitoring Centre),

Nature), MENR (Ministry of Energy and Nation- 1998: Contribution to an evaluation of tree species using

al Resources), 2007: Red List of threatened fauna and the CITES listing criteria. http://www.biodiversitylibrary.

flora of Sri Lanka, Colombo, Sri Lanka. http://cmsdata. org/item/119115.

iucn.org/downloads/rl_548_7_003.pdf.

[22] IUCN (International Union for Conservation of

Nature), 2013: IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

www.iucnredlist.org. The Author:

[23] Jayaraman, U., 1996: Economic importance of the ge- Dr. Joachim Schmerbeck

nus Diospyros L. (Ebenaceae) in India. Indian Forester Chair of Silviculture, Institute of Forest Sciences,

122, 1040–1044. Faculty of Environment and Natural Resources,

[24] Jayasingam, T.; Balasubramaniam, S.; Vivekanantha- University of Freiburg,

rajah, S., 1992: Vegetation survey of the Wasgomuwa Tennenbacher Str 4, 79085 Freiburg,

National Park: Reconnaissance. Vegetatio 101, 171–181. Germany

[25] Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, 2014: Endangered

plants. http://images.kew.org/endangered-plants/pho-

Dr. Niyati Naudiyal

to/44818.html?pn=2&so=1&sci=1397373717&gid=44

818#gridtop. Research Associate, School of Environment and Natural Resources,

[26] Matthew, K. M., 1983: The Flora of the Tamilnadu Doon University, Mothrowala Road,

Carnatic. Rapinat Herbarium, St. Joseph's College. Kedarpur, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India.

12 Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse – 69. Erg. Lfg. 01/17

View publication stats

You might also like

- Cambodian Tree SpeciesDocument61 pagesCambodian Tree Speciesfredericodalmeida33% (3)

- Radio Arch SP Short 2ppDocument42 pagesRadio Arch SP Short 2pprfidguysNo ratings yet

- Clove A Champion SpiceDocument9 pagesClove A Champion SpiceBeelNo ratings yet

- Coconut - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument22 pagesCoconut - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaJoseph Gonsalves0% (1)

- Persoon 2008Document18 pagesPersoon 2008parkmihuNo ratings yet

- La-Ongsri, Trisonthi, Balslev - 2009 - A Synopsis of Thai NymphaeaceaeDocument18 pagesLa-Ongsri, Trisonthi, Balslev - 2009 - A Synopsis of Thai NymphaeaceaeLeandrorvNo ratings yet

- Perez Escobar Et Al 2022 TIPSDocument16 pagesPerez Escobar Et Al 2022 TIPSAnthony PaucaNo ratings yet

- Clove A Champion SpiceDocument9 pagesClove A Champion SpiceYaqeen MutanNo ratings yet

- 2016 - The Origin and Domestication of AquilariaDocument21 pages2016 - The Origin and Domestication of AquilariaArthur LowNo ratings yet

- Hendrichetal.2004Singapore Aquatic BeetleDocument50 pagesHendrichetal.2004Singapore Aquatic BeetleGerald Lee Zheng YangNo ratings yet

- Keanekaragaman Hutan Campur Dipterocarpaceae Dataran RendahDocument15 pagesKeanekaragaman Hutan Campur Dipterocarpaceae Dataran RendahbangunNo ratings yet

- Millind, P., Clove - A - Champion - SpiceDocument9 pagesMillind, P., Clove - A - Champion - SpiceBrian Mukti NugrohoNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER ThesisDocument37 pagesCHAPTER Thesishafiza.areeba2001No ratings yet

- CoconutDocument253 pagesCoconutoana77PNo ratings yet

- 2013 Sipman Diederich Aptroot PalawanDocument13 pages2013 Sipman Diederich Aptroot PalawanJOMAR HEBREWS REJANONo ratings yet

- Studies On Biology and Reproduction of Butterflies (Family: Papilionidae) in Nilgiris Hills, Southern Western Ghats, IndiaDocument11 pagesStudies On Biology and Reproduction of Butterflies (Family: Papilionidae) in Nilgiris Hills, Southern Western Ghats, IndiaEman SamirNo ratings yet

- Odonata Annotated ListDocument14 pagesOdonata Annotated ListJonathan DigmaNo ratings yet

- Junglees Mixed Forest Edited1 PDFDocument167 pagesJunglees Mixed Forest Edited1 PDFRavikumaar RayalaNo ratings yet

- 2061 4074 2 PBDocument6 pages2061 4074 2 PBSITI OLIMFIANo ratings yet

- CG4 16Document6 pagesCG4 16Henrie AgataNo ratings yet

- 2 November 2023 Academic Reading Practice TestDocument16 pages2 November 2023 Academic Reading Practice Testbhargavp1898No ratings yet

- McBride Thesis 2Document33 pagesMcBride Thesis 2joelson temoteoNo ratings yet

- 4.4.20 Viii Science Chapter - 7 Conservation of Plants - 0Document21 pages4.4.20 Viii Science Chapter - 7 Conservation of Plants - 0anandNo ratings yet

- Activity 3Document2 pagesActivity 3Espiritu, ChriscelNo ratings yet

- SCHAFER VERWIMP1999.Dominicaadditions.Document16 pagesSCHAFER VERWIMP1999.Dominicaadditions.cristopher jimenez orozcoNo ratings yet

- Available Online Through: Clove: A Champion SpiceDocument8 pagesAvailable Online Through: Clove: A Champion SpiceCynthia Adilla AriefNo ratings yet

- 2 DeRosaetal PDFDocument8 pages2 DeRosaetal PDFPancasila TPB03No ratings yet

- 2 DeRosaetalDocument8 pages2 DeRosaetalPancasila TPB03No ratings yet

- Orchids of NepalDocument145 pagesOrchids of Nepalshinkaron88100% (1)

- Palmleaves Plosone 0111738Document11 pagesPalmleaves Plosone 0111738supportLSMNo ratings yet

- Eucalyptus Expansion As Relieving and ProvocativeDocument13 pagesEucalyptus Expansion As Relieving and ProvocativeMeilyn Renny PathibangNo ratings yet

- Andres Etal 2017 YamDioscoreaspp.Document9 pagesAndres Etal 2017 YamDioscoreaspp.chukwudinwogboiveNo ratings yet

- Schinus Molle L. (Anacardiaceae) Chicha Production in The Central AndesDocument9 pagesSchinus Molle L. (Anacardiaceae) Chicha Production in The Central AndesMarco ChangNo ratings yet

- LichensDocument20 pagesLichensrimsha sultanNo ratings yet

- Plants Color Cotton ArticleDocument9 pagesPlants Color Cotton ArticleAlberic AkogouNo ratings yet

- Mushroom Utilization by The Iban in Eastern Sarawak, MalaysiaDocument5 pagesMushroom Utilization by The Iban in Eastern Sarawak, Malaysiasupriyanto untanNo ratings yet

- Cap. 08 - RabbitsDocument23 pagesCap. 08 - RabbitsNailson JúniorNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 The EnvironmentDocument11 pagesUnit 5 The EnvironmentAdjepoleNo ratings yet

- Arthropods Associated With Dipterocarp Saplings at Eco-Park Conservation Area, Los Baños, Laguna, PhilippinesDocument7 pagesArthropods Associated With Dipterocarp Saplings at Eco-Park Conservation Area, Los Baños, Laguna, PhilippinesEzekiel InfantadoNo ratings yet

- Tardigrades Species RelationshipsDocument12 pagesTardigrades Species RelationshipsAxel Gómez-Ortigoza100% (1)

- On The Ecology and Behavior of Cebus Albifrons. I. EcologyDocument16 pagesOn The Ecology and Behavior of Cebus Albifrons. I. EcologyMiguel LessaNo ratings yet

- Medicinalpropertiesofsome Dendrobiumorchids AreviewDocument11 pagesMedicinalpropertiesofsome Dendrobiumorchids AreviewCherie Anne GrospeNo ratings yet

- The Coconut CrabDocument46 pagesThe Coconut CrabJulio IglasiasNo ratings yet

- Ackerman 1983Document11 pagesAckerman 1983Renato VianaNo ratings yet

- The Rtu Orchid Micro-Propagation GuidebookDocument79 pagesThe Rtu Orchid Micro-Propagation GuidebookAnonymous HXLczq3100% (8)

- Dryobalanops, The Potential Tree Species Endangered To Become Almost ExtinctDocument12 pagesDryobalanops, The Potential Tree Species Endangered To Become Almost ExtinctgsmLina R PanyalaiNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER II Delulu GirlsDocument11 pagesCHAPTER II Delulu GirlsjellianoznolaNo ratings yet

- OLENepal2010 DifferentKindsOfOrchidDocument12 pagesOLENepal2010 DifferentKindsOfOrchidsatyaNo ratings yet

- 2007PJSBAlejandro PDFDocument15 pages2007PJSBAlejandro PDFEd Doloriel MoralesNo ratings yet

- AfrocersiskenyensisGOK PublicationDocument8 pagesAfrocersiskenyensisGOK PublicationAyan DuttaNo ratings yet

- Bamboo Research in The Philippines - Cristina ADocument13 pagesBamboo Research in The Philippines - Cristina Aberigud0% (1)

- Notes - Conservation of BiodiversityDocument2 pagesNotes - Conservation of BiodiversityAmrin FathimaNo ratings yet

- Science Adf5842Document5 pagesScience Adf5842richardNo ratings yet

- Canne de ProvenceDocument8 pagesCanne de Provenceicar aphroditeNo ratings yet

- Enochrus de TurquiaDocument7 pagesEnochrus de TurquiaMauricio GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Day 1 - FulltestDocument20 pagesDay 1 - Fulltestevaclamdong.eduNo ratings yet

- Biology Project Work Investigatory Project1Document22 pagesBiology Project Work Investigatory Project1Akash Majhi70% (27)

- Conservation of Plants & Animals - Class 8: We Know That Large Varieties of Plants and Animals Are Present On EarthDocument33 pagesConservation of Plants & Animals - Class 8: We Know That Large Varieties of Plants and Animals Are Present On Earthstory manNo ratings yet

- Terminal 2 ExamDocument5 pagesTerminal 2 ExamMani VannanNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Questions in Ray OpticsDocument9 pagesDifference Between Questions in Ray OpticsMani VannanNo ratings yet

- XII Final ACP 1Document34 pagesXII Final ACP 1Mani VannanNo ratings yet

- Class 6 PhysicsDocument5 pagesClass 6 PhysicsMani VannanNo ratings yet

- Half Yearly Exam of Class ViiDocument7 pagesHalf Yearly Exam of Class ViiMani VannanNo ratings yet

- Exp 5Document5 pagesExp 5Mani VannanNo ratings yet

- 10 EnglishDocument8 pages10 EnglishMani VannanNo ratings yet

- Grade 7 Dec ExamDocument3 pagesGrade 7 Dec ExamMani VannanNo ratings yet

- Grade 6 SocialDocument34 pagesGrade 6 SocialMani VannanNo ratings yet

- Cbjeenpu 05Document8 pagesCbjeenpu 05Mani VannanNo ratings yet

- Galaxy - Unit Test - 1 - BiologyDocument4 pagesGalaxy - Unit Test - 1 - BiologyMani VannanNo ratings yet

- Mock Exam - Grade 7 UpdatedDocument6 pagesMock Exam - Grade 7 UpdatedMani VannanNo ratings yet

- My Dream Statement V1.3Document3 pagesMy Dream Statement V1.3Mani VannanNo ratings yet

- Activity For 12 Physics LabDocument10 pagesActivity For 12 Physics LabMani VannanNo ratings yet

- Collision Bar Ve Jayaram AnDocument8 pagesCollision Bar Ve Jayaram AnMani VannanNo ratings yet

- Strange Heart of Neutron StarDocument3 pagesStrange Heart of Neutron StarMani VannanNo ratings yet

- WWW Dailymail Co Uk News Article 9710873 Well Having Covid Jabs 10 YEARS Predicts Chris Hopson NHS Providers HTMLDocument1 pageWWW Dailymail Co Uk News Article 9710873 Well Having Covid Jabs 10 YEARS Predicts Chris Hopson NHS Providers HTMLMani VannanNo ratings yet

- 5 6197451419432256293 PDFDocument65 pages5 6197451419432256293 PDFMani VannanNo ratings yet

- Perhitungan Sambungan End Plate Terhadap Mini Kolom Dan Balok A. Data-DataDocument51 pagesPerhitungan Sambungan End Plate Terhadap Mini Kolom Dan Balok A. Data-DataAchmad Zaki ZulkarnainNo ratings yet

- Traffic and Road Safety Act, 1998 (Amendment) Act 2020Document56 pagesTraffic and Road Safety Act, 1998 (Amendment) Act 2020kityamuwesiNo ratings yet

- Theophylline.: BNF DrugsDocument2 pagesTheophylline.: BNF Drugsgege0% (1)

- The Transformation of Cu (Oh) Into Cuo, Revisited: 2 Yannick Cudennec, André LecerfDocument4 pagesThe Transformation of Cu (Oh) Into Cuo, Revisited: 2 Yannick Cudennec, André LecerfJose David CastroNo ratings yet

- PLC Interview QuestionsDocument2 pagesPLC Interview QuestionsSushant100% (1)

- Physics Lesson Notes On Heat Capacity and Specific Heat CapacityDocument5 pagesPhysics Lesson Notes On Heat Capacity and Specific Heat CapacityAwajiiroijana Uriah OkpojoNo ratings yet

- IAB - Quinn-Lite BlocksDocument13 pagesIAB - Quinn-Lite BlocksCormac DooleyNo ratings yet

- Manila Bay CruiseDocument2 pagesManila Bay CruiseEloise PateñoNo ratings yet

- Mercy ProposalDocument14 pagesMercy Proposalmichaelnicodemus93No ratings yet

- Bedienungshandbuch CM UKDocument64 pagesBedienungshandbuch CM UKIoana MarchisNo ratings yet

- Economics of Natural ResourcesDocument14 pagesEconomics of Natural ResourcesRinkesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Booth MultiplierDocument5 pagesBooth MultiplierSyed HyderNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study On I Girder and Box Girder For Design of PSC BridgeDocument10 pagesComparative Study On I Girder and Box Girder For Design of PSC BridgePrabhnoorNo ratings yet

- Resurrection: Mahler Symphony No. 2Document15 pagesResurrection: Mahler Symphony No. 2MateoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 19 Physics 6Document62 pagesChapter 19 Physics 6Cristian Medina ChirinosNo ratings yet

- Movie Disasters!: VocabularyDocument2 pagesMovie Disasters!: VocabularyYesica SisaNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence BasicsDocument2 pagesArtificial Intelligence BasicsDennis DubeNo ratings yet

- Brochure Starex PDFDocument6 pagesBrochure Starex PDFMohammad Jailani A Jamil100% (1)

- Chem 331 Quiz KeysDocument4 pagesChem 331 Quiz KeysJacob HorgerNo ratings yet

- CUNANAN LENS AND MIRRORS FinalDocument7 pagesCUNANAN LENS AND MIRRORS Finalvcunanan20ur0411No ratings yet

- Postal 3 User ManualDocument47 pagesPostal 3 User ManualsotoorNo ratings yet

- CYKADocument8 pagesCYKAEdouard HalaszNo ratings yet

- Nutritional AssessmentDocument4 pagesNutritional Assessmentchindobr8No ratings yet

- B+V ELEVATOR Slip Type BVT Tubing VS11 A4Document2 pagesB+V ELEVATOR Slip Type BVT Tubing VS11 A4AhmedNo ratings yet

- 447.010 Screen Operating Manual v001Document67 pages447.010 Screen Operating Manual v001José CarlosNo ratings yet

- Design of Knuckle JointDocument26 pagesDesign of Knuckle Jointvikasporwal2605100% (2)

- R4V-R6V Uk-2Document9 pagesR4V-R6V Uk-2Zoran JankovNo ratings yet

- 01-Block DiagramDocument1 page01-Block Diagramkhoi vuNo ratings yet

- SPD eRAN7.0 CA Feature Introduction-20140228-A-1.0Document32 pagesSPD eRAN7.0 CA Feature Introduction-20140228-A-1.0KhanNo ratings yet