A Land on the

Threshold

��A Land on the

Threshold

South Tyrolean Transformations,

1915–2015

Edited by Georg Grote

and Hannes Obermair

PETER LANG

Oxford • Bern • Berlin • Bruxelles • Frankfurt am Main • New York • Wien

�Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche

Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at

http://dnb.d-nb.de.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016963047

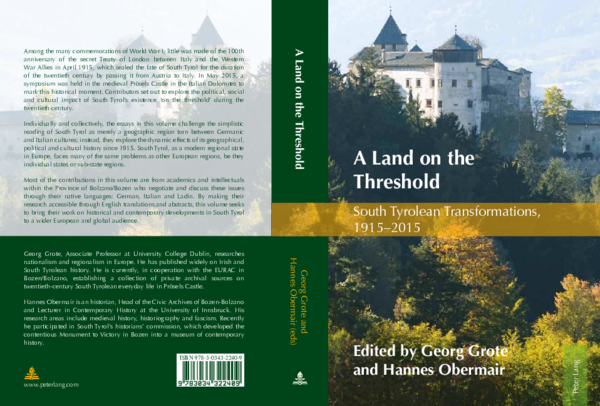

Cover image: Prösels Castle near Völs am Schlern. Photograph by Georg Grote.

Cover design: Peter Lang Ltd.

ISBN 978-3-0343-2240-9 (print) • ISBN 978-1-78707-420-0 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-1-78707-421-7 (ePub) • ISBN 978-1-78707-422-4 (mobi)

© Peter Lang AG, International Academic Publishers, Bern 2017

Wabernstrasse 40, CH-3007 Bern, Switzerland

info@peterlang.com, www.peterlang.com, www.peterlang.net

All rights reserved.

All parts of this publication are protected by copyright.

Any utilisation outside the strict limits of the copyright law, without the permission of the publisher, is forbidden and liable to prosecution.

This applies in particular to reproductions, translations, microfilming, and storage

and processing in electronic retrieval systems.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

Printed in Germany

�Contents

List of Figures�

ix

Acknowledgements�xiii

Georg Grote and Hannes Obermair

Introduction: South Tyrol: Land on a Threshold. Really?�

part i

History�

xv

1

Rolf Steininger

1 1918/1919. Die Teilung Tirols�

3

Carlo Moos

2 Südtirol im St. Germain-Kontext�

27

Nina F. Caprez

3 �Economic Hurdles after the Great War: How the South

Tyrol-based Swiss Monastery Muri-Gries Overcame an

Existential Crisis�

41

Sabine Mayr

4 �The Annihilation of the Jewish Community of Meran�

53

�vi

part ii

Historiography�

77

Markus Wurzer

5 �Genesis of the South Tyrolean Iconic Figure Sepp Innerkofler:

Actors, Narrative, Functions�

79

Georg Grote

6 �Challenging the Zero-Hour Concept: Letters across Borders�

101

Eva Pfanzelter

7 �The (Un)digested Memory of the South Tyrolean

Resettlement in 1939�

part iii

Society Today�

119

145

Sarah Oberbichler

8 �“Calcutta lies … near the Rombrücke”: Migration Discourse

in Alto Adige and Dolomiten and their Coverage of the Bozen

“Immigrant Barracks Camps” of the Early 1990s�

147

Julia Tapfer

9 �Ankommen, verbinden, vernetzen: Vereine und

Vereinigungen von Migrant_innen in Südtirol. Eine

Gegenüberstellung der Donne Nissà, der Associazione

Panalbanese Arbëria und der Rumänischen Gemeinde�

173

Friederike Haupt

10 Beobachtungen aus musiksoziologischer Sicht�

197

�vii

Bettina Schlorhaufer

11 �Historicism and the Rise of Regionalism as “Style”:

South Tyrol’s Successful Special Path�

217

Gareth Kennedy

12 �

Die Unbequeme Wissenschaft (The Uncomfortable Science)�239

part iv

Border Stories�

257

Johanna Mitterhofer

13 �Border Stories: Negotiating Life on the Austrian–

Italian border�

259

Paolo Bill Valente

14 Sulla soglia. Leggende meranesi, storie di confine�

275

Marta Villa

15 �Identità e riconoscimento attraverso i culti della fertilità e

il paesaggio agricolo nel Tirolo del Sud. Il case study della

popolazione giovane maschile di Stilfs in Vinschgau�

part v

Renegotiating Belonging�

287

305

Antonio Elorza

16 �Alsace, South Tyrol, Basque Country (Euskadi):

Denationalization and Identity�

307

Lucio Giudiceandrea and Aldo Mazza

17 Living Together is an Art�

327

�viii

Hans Karl Peterlini

18 �Between Stigma and Self-Assertion: Difference

and Belonging in the Contested Area

of Migration and Ethnicity�

341

Barbara Angerer

19 �Living Apart Together in South Tyrol: Are Institutional

Bilingualism and Translation Keeping Language Groups Apart?� 361

Siegfried Baur

20 �Grenzregion Südtirol. Schwierigkeiten und Möglichkeiten

einer Erziehung zur Mehrsprachigkeit für ein vielsprachiges

Europa�381

Chiara De Paoli

21 �Redefining Categories: Construction, Reproduction and

Transformation of Ethnic Identity in South Tyrol�

Notes on Contributors�

395

409

Index�415

�Figures

Figure 3.1:

Places relevant to the monastery of Muri-Gries

and its post-war history. �

46

Figure 8.1:

Argumentation patterns in Alto Adige (157 articles).�

156

Figure 8.2:

Argumentation patterns in Dolomiten (58 articles).�

157

Figure 11.1:

Villa Ultenhof after completion, around 1900.

The representative estate and its historical garden

still exist today. Photo: Archivio civico di Merano,

sign. 16881.�

227

Figure 11.2:

Perspective of the Villa Ultenhof. This sketch

was probably designed by the local artist Tony

Grubhofer for Musch & Lun (see also Figure 11.3).

Perspective: Musch & Lun Archive, Thomas

Kinkelin, Merano. Graphic processing: Olaf Grawert.� 228

Figure 11.3:

Villa Hübel was published by Musch & Lun

already in 1899, illustrated with a perspective

which was created by the reknown local artist

Tony Grubhofer (1854–1935). In: Der Architekt,

Wiener Monatshefte für Bauwesen und decorative

Kunst, 5th year (Vienna: 1899), p. 3 and table 5.�

229

Figures 11.4, Villa Ultenhof, ground floor plan. The floor plan

11.5 and 11.6: �of the Villa Ultenhof corresponds to a mainrequirement of the Anglo–American Picturesque.

Floor plan: Musch & Lun Archive, Thomas

Kinkelin, Merano. Graphic design: Olaf Grawert.� 230–231

Figure 11.7:

The original Ansitz Reichenbach was an elongated

building in the narrow, sloping Reichenbachgasse

(Reichenbach alley). Photo: Archivio civico di

Merano, sign. 17431.�

233

�x

Figure 11.8:

Figures

Schloss Reichenbach after conversion. Photo:

F. Peter, 1905, Archivio civico di Merano, sign. 8207.� 234

Figures 11.9 M

� usch & Lun, conversion of Ansitz Reichenbach

and 11.10:

into Schloss Reichenbach. Plans: Musch & Lun,

Archivio civico di Merano, sign. 17435d and

17435d, undated.�

235

Figures 11.11 U

� nfortunately a plan of Schloss Reichenbach’s

and 11.12:

south façade doesn’t exist. A reconstruction was

made after a photomontage, 2015. Graphic design

and photomontage: Olaf Grawert.�

236

Figure 12.1:

Mediathek. Production image at the

Österreichische Mediathek, Vienna, featuring

the Richard Wolfram film Egetmann in Tramin,

colour 16mm film transferred to digital. 3.23 min.

Courtesy of Gareth Kennedy.�

Figure 12.2: Maskenschnitzer. Production image featuring

woodcarver Lukas Troi with the mask of Alfred

Quellmalz, ethnomusicologist with the SS

Ahnenerbe Kulturkommission to South Tyrol.

Courtesy of Gareth Kennedy.�

Figure 12.3:

245

248

Stuben-Forum. Contemporary hanging stube for

housing Maskenschnitzer, 16mm film transferred

to HD digital. 13.15 min. Design by Harry Thaler.

Fabrication by Kofler with Deplau and Rothoblas.

Gareth Kennedy, Die Unbequeme Wissenschaft

(2014). Image by Serena Osti.�

249

Figure 12.4: Installation view of Die Unbequeme Wissenschaft

at ar/ge Kunst, Bozen/Bolzano, South Tyrol.

Showing the contemporary hanging stube and the

mask of Bronislaw Malinowski carved by Robert

Griessmair. Gareth Kennedy, Die Unbequeme

Wissenschaft (2014). Image by Serena Osti.�

250

Figure 12.5:

Framing Volkskunde. Unsere Frau/Schnals.

Original photographs from the Alfred Quellmalz

�xi

Figures

Archive framed for Die Unbequeme Wissenschaft.

Note the staged lighting and Quellmalz’s probing

microphone. Courtesy of the Referat Volksmusik,

Bozen/Bolzano.�251

Figure 12.6: Axis at the Egetmann. The Axis at the Egetmann

procession in Tramin for its “final” performance for

the Ahnenerbe lens. Wolfram Sievers, Prefetto of

Trento Italo Foschi and SS Obersturmbannführer

Dr Wilhelm Luig of ADERSt enjoying the

performance of the Egetmann procession at Walch

Kellerei, Tramin, South Tyrol, February 1941.

Courtesy of the private collection of Nicholas Kasel.� 252

Figure 12.7: Stuben-Forum. Stuben-Forum held at ar/ge Kunst

on 20 September 2014. Speakers (from left): Franz

Haller, visual anthropologist; Hannes Obermair,

historian; Elizabeth Thaler and Ina Tartler, Bozen

Stadttheater; Hans Karl Peterlini, journalist and

author; Thomas Nußbaumer, ethnomusicologist,

University of Innsbruck; Georg Grote, Professor

of German Studies, University College Dublin.

Courtesy of Gareth Kennedy.�

Figure 13.1:

Figure 19.1:

The location of the places referred to in Chapter

13, “Border Stories: Negotiating Life on the

Austrian–Italian border”.�

261

Self-assessment for L2 competence levels B2/C2,

CEFR (ASTAT 2006).�

364

Figure 19.2: Bi-communitarian bilingualism in Südtirol/

Alto Adige. Adapted from Berruto (2003: 213).�

Figure 19.3:

254

365

An original public administration document

and its translation presented in two columns.

See: <http://www.provinz.bz.it/anwaltschaft/

download/G_2010–170.pdf>.�380

��Acknowledgements

The editors of this volume would like to express their gratitude to all contributors, to the Peter Lang team for their support, University College Dublin,

the Institute for Minority Rights in the EURAC and the Stadtarchiv Bozen,

the Prösels Castle Kustos Michl Rabensteiner and the Kuratorium Schloss

Prösels for the use of the castle facilities on 8 and 9 May 2015, the Völser

Goldschmiede, the Binderstube and the Caffè Caroma in Völs, and to the

Hotel Heubad in Obervöls for their generous support.

��Georg Grote and Hannes Obermair

Introduction: South Tyrol:

Land on a Threshold. Really?

While South Tyrol is a part of Italy, it is also an autonomous province

with distinct Austrian and German characteristics. Both South Tyrol’s

geographic location and history underscores its position as a region

where the north meets the south of Europe: at its border, Italian and

German cultures and languages converse and Mediterranean and northern European climates collide. Hence, it has regularly been described as

an “Übergangsland” – as a passage from north to south and vice versa.

It has, however, been a contested region for 150 years, and political viewpoints have often characterized the approach of writers and commentators towards this mountainous region in the Central Alps. Depending

on the source and context, the region has been claimed as a German or

Italian one; only in recent years has there been a growing tendency to

regard the region as both German and Italian.1 It is this latter tendency

to view South Tyrol as a unique hybrid of both these cultures that this

volume wishes to explore through the prism of various disciplines. While

the German and Italian influences may not always harmonize with each

other, this collection of essays reveals that they do inform and enrich

the region resulting in a complex and diverse collective culture that is

modern South Tyrol.

Nothing has epitomized the German and Italian claims on South

Tyrol as succinctly as the name of the area itself: Südtirol (South Tyrol)

in German, Alto Adige in Italian. In many respects the word pair Alto

1

See Lucio Giudiceandrea, Spaesati, Italiani in Südtirol (Bozen: Raetia, 2007); and

Lucio Giudiceandrea and Aldo Mazza, Stare insieme è un’arte. Vivere in Alto Adige/

Südtirol (Meran: alphabeta, 2012).

�xvi

Georg Grote and Hannes Obermair

Adige/South Tyrol hints at its complexity. Where there is a South Tyrol,

there should be a North Tyrol, otherwise there would be no need to add

the prefix “South” to distinguish one part of the landscape from another.

North Tyrol is part of another independent state, Austria, which is located

beyond the Brenner border. South Tyrol therefore highlights a connection

to an area outside the Italian state. Those who call the region South Tyrol

today, the vast majority of the 320,000 German-speaking South Tyroleans,

keep alive the memory of the division of Tyrol in 1918 and a loyalty to a

historical unity with Austria. They also stress their cultural affinity with

the German-speaking world beyond the Brenner Pass.

Alternatively, the fact that the 160,000 Italians in South Tyrol refer

to the region as Alto Adige, the high Etsch/Adige region, implies that

there must be a lower Etsch/Adige region. As the river Etsch/Adige flows

from the Austrian–Italian–Swiss border down through the Vinschgau/

Val Venosta, unites with the river Eisack/Isarco and then flows to central

Italy, this lower Etsch/Adige region is in Italy where the river flows into

the Adriatic Sea. The Italian name for the region therefore emphasizes

its geographical connection to the entire Italian landscape: it is literally

drawing the region into the Italian homeland. Thus the two names for the

region are not merely German and Italian versions of each other, they are,

in fact, linguistic attempts to appropriate the area, based on competing

political and cultural understandings of the region.

Claims old and new

It is widely accepted that the dispute over where South Tyrol belonged – to

which state it should affiliate – began in 1866 with the leading exponent

of Italian emancipatory nationalism, Giuseppe Mazzini. Mazzini claimed

that only 20 per cent of the Tyrolean people living south of the Brenner

Pass were of German origin and thus a minority easy to Italianize. The area,

therefore, belonged to Italy and should become part of the new Italian

�Introduction: South Tyrol: Land on a Threshold. Really?

xvii

state.2 By the 1890s, the pro-Italian nationalist Ettore Tolomei had developed a pseudo-scientific argument that Italy’s boundaries were defined by

nature and not by the ethnicity of the region’s population.3 This view went

against the grain of contemporary nationalist sentiment across Europe,

which regarded ethnicity as the marker of borders. Tolomei’s rationale

was contested by an alternative Austrian–German vision expounded by

various groups, in particular, the Tiroler Volksbund established in 1905.

This Austrian–German cultural and political movement articulated a competing desire to see a Germanized Northern Italy as far south as Verona.4

Thus, on the eve of World War I, South Tyrol was in the eye of a cultural storm with two distinct and, apparently, incompatible views of the

region’s cultural identity and political future. Hence in the early stages

of the conflict, Italy played its political hand with its ambitions regarding South Tyrol firmly in its sights. In 1915, when it was far from certain

that the Austrian–German alliance would lose the war, Italy joined forces

with the Western Allies. Its strategy paid off when in 1918, as part of the

spoils of war, it was rewarded with the southern part of the Austrian

crownland Tyrol.

When Mussolini came to power in late 1922, he tightened the Italian

grip on South Tyrol by embarking on a Tolomei-led campaign of Italianizing

the German-speaking population. The fascists attempted to Italianize all

areas of individual and collective life in order to eradicate any traces of

the Austrian–German tradition: place names and family names were

Italianized; the only language accepted was Italian; and all kinds of Tyrolean

collective organizations and newspapers were suppressed.5 In the face of

such fascist suppression, many Tyroleans welcomed Hitler’s declaration

that all German peoples belonged in the German Reich. However, Hitler

was more interested in securing Mussolini’s friendship and creating the

fascist axis in Europe than protecting or supporting German-speaking

2

3

4

5

Rudolf Lill, Südtirol in der Zeit des Nationalismus (Konstanz: Universitätsverlag

Konstanz, 2002), p. 26.

Georg Grote, The South Tyrol Question (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2012), pp. 15–18.

Rolf Steininger, Südtirol im 20.Jahrhundert (Innsbruck: Studienverlag, 1997), p. 259.

Grote, South Tyrol Question, pp. 35–52.

�xviii

Georg Grote and Hannes Obermair

South Tyroleans. Consequently, an agreement between the two fascist

governments in Berlin and Rome in 1938 presented the German-speaking

South Tyroleans with an option: if they wished to remain German-speaking

and thus part of the Germanic cultural sphere, they had to physically emigrate to the German Reich, or remain in their “Heimat” in Italy and give up

their loyalty to their Austrian–German language and tradition. This was

a scenario that quite literally tore the German-speaking South Tyroleans

apart through bitter disputes. By 31 December 1939, 86 per cent declared

they were willing to leave, but, due to the wartime developments, only

75,000 actually managed to leave and of these 25,000 returned after 1945.

The Option is still remembered as a traumatic event in South Tyrolean

history because it symbolizes the limits of internal solidarity among the

German-speaking population.6

Even after the end of fascism in Rome and Berlin in 1945, when all

chances of reunification with Austria were truly dashed, many Germanspeaking South Tyroleans continued to harbour hopes of an end to Italian

rule in the region or at least an end to Italianization. It was generally

believed that the historic injustice of St Germain, the partition of Tyrol,

would be remedied and Tyrol would be reunited. After 1945, the Cold

War emerged swiftly and the Western Allies’ agenda to contain Stalin and

communism took precedence over the fate of a small minority, which

was also tarnished by its (alleged) sympathy for the German Reich. Italy

managed to hold on to South Tyrol and, as Italian post-war domestic

politics underwent no radical break with its past, unlike in Austria and

Germany, South Tyroleans soon felt oppressed again by what they perceived as a continuation of fascist policies of Italianization in the province.

Dissatisfaction smouldered over the years and finally erupted in what

has become known as the “Bombenjahre” in the mid-1950s, a violent

period of terrorist attacks on Italian infrastructure and representatives

6

Much has been written about the cultural and psychological impact of this Option

period, which tore families apart and left a lasting legacy of bitterness and pain, and

it is still claiming a major part of South Tyrolean historiography, see, for example,

Eva Pfanzelter’s article in Chapter 7 of this volume.

�Introduction: South Tyrol: Land on a Threshold. Really?

xix

in South Tyrol and beyond which continued into the 1960s.7 It was not

until the intervention of the United Nations and the ratification of the

South Tyrolean autonomy in 1972 that South Tyrol finally embarked on

a regionalist course within the framework of regional development stipulated by the European Economic Community. Within this programme

of regional development and political engagement with the regions of

Europe the protection of South Tyrol’s German-speaking population

has achieved its full potential. It has resulted in a lasting appeasement

with Italy, but also to the creation of a remarkable state-like regional

self-confidence, distinct from both Italy and Austria.8

The “Regional State” South Tyrol has many of the hallmarks of historical nation-building, for example, the emergence of national literature

and an accepted culture of writing history and commemorating crucial

historical events central to the region’s development. Hans-Karl Peterlini’s

recent history of the province, 100 Jahre Südtirol – Geschichte eines jungen

Landes [100 Years of South Tyrol – History of a Young Country], testifies to this development. This publication sits beside other German

language monographs on key events of the past 100 years and the biographies of the “founding fathers” of the “regional state”, among them

the protagonists of the bombing campaigns in the 1960s and significant

politicians.

Hence, it can be argued that South Tyrol has transformed its position

on the proverbial threshold into its raison d’être. The region defines its

international significance by the strength of its autonomy and in providing a powerful example of the potential role European regions can play

in the politics and culture of the EU. South Tyrol generally sees itself as a

distinct entity, no longer as an area precariously perched between worlds,

states and cultures, but as a region drawing strength from its political and

geographical position and its cultural complexity.

7

8

Grote, South Tyrol Question, pp. 85–113.

Grote, I bin a Südtiroler. Regionale Identität zwischen Nation und Region (Bozen:

Athesia, 2009), pp. 225–250.

�xx

Georg Grote and Hannes Obermair

The modern land and its issues

Spring 2015 heralded the hundredth anniversary of the secret treaty of

London that sealed the fate of South Tyrol for the duration of the twentieth century, when this part of Habsburg’s crown colony was handed to

Italy. While the German-speaking South Tyroleans have often stressed

their histo-cultural allegiance with the Germanic world, the 1915 treaty

resulted in the creation of new loyalties and new societal developments.

The twentieth century would bring to the region war and violence, two

dictatorships (Italian fascism and German national socialism), democracy,

republicanism, peace initiatives, political wisdom and economic affluence,

which have accompanied and influenced the drawn-out societal changes.

A symposium was held in the medieval Castle Prösels in the Italian

Dolomites in May 2015 to mark the hundredth anniversary of the 1915

London treaty. Contributors set out to explore through various disciplines

the political, social and cultural impact of South Tyrol’s existence on the

threshold during the twentieth century. Individually and collectively the

essays in this volume challenge the simplistic reading of South Tyrol as

merely a geographic region torn between two cultures; instead they explore

the dynamic effects of its geographical, political and cultural history since

1915. South Tyrol is presented here as an institutional and state-like entity,

a region facing very similar problems to many other regions in Europe, be

they individual states or sub-state regions. Most of these contributions are

from academics and intellectuals within the Province of Bolzano/Bozen

who are used to negotiating and discussing these issues through their native

languages German, Italian and Ladin. This volume seeks to bring their work

and the history and development of South Tyrol to a wider European and

global audience, hence the chosen language of English.

The volume is subdivided into five thematic parts. In Part I Rolf

Steininger analyses the steps towards partition in 1918; Carlo Moos explores

the mechanics of the post-World War I St Germain Treaty negotiations;

and Nina F. Caprez investigates the consequences of the partition for the

economic survival of the monastery Muri-Gries. Finally, Sabine Mayr

�Introduction: South Tyrol: Land on a Threshold. Really?

xxi

provides an insight into the fate of the Jewish community in Meran during

the early part of the twentieth century.

Part II explores the historiography of the region: Marcus Wurzer

demystifies and re-contextualizes the World War I hero Sepp Innerkofler;

Georg Grote explores the realities of a zero hour in Austria, Germany and

Italy for ordinary people by exploring hundreds of letters written by a

couple suddenly divided by borders; and Eva Pfanzelter critically evaluates

the commemoration of the Option period.

Part III focuses on current challenges the province faces: Sarah

Oberbichler investigates how major provincial newspapers presented the

migration issue in the early 1990s; Julia Tapfer offers an analysis of how

migrant societies have fared in South Tyrol; Friederike Haupt and Bettina

Schlorhaufer analyse South Tyrolean regionalism in the arenas of music

and architecture; and Irish artist Gareth Kennedy explores how anthropology was conducted in South Tyrol during the period of the Third Reich.

Part IV deals with the existence of borders and their relevance for

South Tyrol’s communities: Johanna Mitterhofer investigates life on the

Austrian–Italian border; Paolo Valente looks at the significance of borders

in the Meran area; and Martha Villa takes a detailed look at the small

border community of Stilfs.

Finally, Part V adds to the ongoing discussion on belonging in South

Tyrol: Antonio Elorza compares and contrasts the situations in Alsace, the

Basque Country and South Tyrol; Aldo Mazza and Lucio Giudiceandrea

argue that cohabitation of different linguistic groups in South Tyrol equals

art; Hans-Karl Peterlini analyses difference and belonging in migration and

ethnicity; Barbara Angerer and Siegfried Baur both investigate the use of

language in the process of cohabitation of German- and Italian-speaking

populations; and Chiara de Paoli challenges existing definitions of ethnic

identity.

��part i

History

��Rolf Steininger

1 1918/1919. Die Teilung Tirols

abstract

Rolf Steininger sets the stage for the story of South Tyrol as we know it today, which

began at the end of World War I, describing in detail the effects of the ceasefire and the

ensuing Treaty of St. Germain agreements on the population and political life in South

Tyrol. He also analyses the initially ambivalent Italian rule over its new province while

Tyrolean politicians north and south of the Brenner Pass protested vociferously against

the perceived injustice resulting from the partitioning of the country, despite Woodrow

Wilson’s political ideals.

Die militärische Niederlage der Mittelmächte besiegelte auch das Schicksal

Tirols. Alle Versuche von Seiten Österreichs und Tirols, die Einheit des

Landes zu retten, schlugen fehl. Am Ende der Friedensverhandlungen in

St. Germain wurde Südtirol als „billige“ Kriegsbeute Italien zugeschlagen

und am 10. Oktober 1920 offiziell annektiert. Bei allen Untersuchungen

über dieses Thema steht ein Mann im Mittelpunkt, der letztlich für diese

Entscheidung verantwortlich gemacht wird: der amerikanische Präsident

Woodrow Wilson. Er galt seit den von ihm im Januar 1918 verkündeten

14 Punkten als Garant für das Selbstbestimmungsrecht der Völker, das

Grundlage künftiger Friedensverhandlungen werden sollte. Am Ende waren

die von der Missachtung dieses Prinzips Betroffenen zutiefst enttäuscht und

voll Verachtung für diesen Mann. Das betraf nicht nur Österreich und Tirol,

sondern auch Deutschland. Als Wilson 1924 starb und in Washington auf

den Botschaftsgebäuden die Fahnen auf Halbmast gesetzt wurden, erhielt

der deutsche Botschafter aus Berlin die Anweisung, dies nicht zu tun – ein

diplomatischer Eklat erster Ordnung.

�4

Rolf Steininger

In Punkt 9 der 14 Punkte hatte es geheißen: „Es sollte eine

Berichtigung der Grenzen Italiens nach den klar erkennbaren Linien der

Nationalität durchgeführt werden.“1 Wäre es nur danach gegangen, hätte

es eine Grenze am Brenner nicht geben dürfen. Tatsache ist, dass die 14

Punkte als „Grundsatzerklärung“ von den Verlierern maßlos überschätzt

worden sind. Bindender und verpflichtender als noch so schön klingende

„Grundsatzerklärungen“ waren Verträge, die während des Krieges abgeschlossen worden waren. Und mit Blick auf Südtirol gab es jenen „Londoner

Vertrag“, den Italien, Großbritannien, Frankreich und Russland am 26. April

1915 unterzeichnet hatten (dessen Anerkennung Wilson allerdings immer verweigert hatte). Darin wurden Italien gegen Norden und Osten das Maximum

der Hauptwasserscheide, das Trentino und das cisalpine Tirol „in seiner

geographischen und natürlichen Grenze“, ferner die Länder Görz und die

Gradiska, das Einzugsgebiet des Isonzo und der Krainische Distrikt Idria

sowie Triest und die Halbinsel Istrien zugesagt.2 Wie war es dazu gekommen?

Seit 1882 war Italien im „Dreibund“ mit Österreich-Ungarn

und dem Deutschen Reich verbündet. Nach der Kriegserklärung des

Habsburgerreiches an Serbien am 28. Juli 1914 beschloss die Regierung in

Rom am 31. Juli die Neutralität Italiens, auch aus Protest dagegen, dass „die

Verständigung der Verbündeten“,3 wie es im Vertrag hieß, unterblieben war.

Berlin und Wien hatten allen Grund, gegenüber Italien misstrauisch zu sein,

waren doch bereits während des Balkankrieges geheime Informationen über

Rom bis nach St. Petersburg gelangt.4 Laut Artikel VII des Dreibundvertrages

hatte Italien durch das österreichisch-ungarische Vorgehen auf dem Balkan

Anspruch auf Kompensationen. Bereits am 2. August wurde vom italienischen Außenminister als Kompensationswunsch das Trentino genannt.

Berlin übte damals starken Druck auf die Regierung in Wien aus, Italien

1

2

3

4

Herbert Michaelis und Ernst Schraepler (Hrsg.), Ursachen und Folgen (Berlin o. J.:

Band 2), S. 375.

Hanns Haas, „Südtirol 1919“, in: Handbuch zur Neueren Geschichte Tirols, Bd. 2,

Zeitgeschichte, hrsg. v. Anton Pelinka u. Andreas Meislinger (Innsbruck: 1993), S. 96.

Josef Fontana, Geschichte des Landes Tirol, Bd. 3. Die Zeit von 1848 bis 1918 (BozenInnsbruck-Wien: 1987), S. 28.

Ebd., S. 427.

�1918/1919. Die Teilung Tirols

5

territoriale Zugeständnisse zu machen. Wien allerdings stand einer

Abtrennung altösterreichischer Gebiete äußerst unwillig gegenüber; die

entsprechenden Vorstöße der Deutschen wies man mit dem Vergleich

einer Abtrennung Elsass-Lothringens an Frankreich zurück. Außerdem

befürchtete man, bei einem noch so kleinen Gebietszugeständnis an eine

andere Nation einen Präzedenzfall zu schaffen, dessen Ausweitungen unabsehbar wären.

In Wien versuchte man in der Folgezeit, bei den Verhandlungen mit

Italien Zeit zu gewinnen. Es ist eine offene Frage, ob dies eine vertane

Chance auf Seiten Wiens gewesen ist. Am 29. Januar 1915 forderte der

italienische Botschafter in Wien, Herzog von Avarna, offiziell eine „territoriale Konzession aus dem Besitz der Monarchie“. Am 9. März, nach einer

weiteren Intervention und verstärktem Druck aus Berlin, erklärte der österreichische Außenminister, Baron Stefan von Burián, seine grundsätzliche

Bereitschaft zur Abtretung von k. u. k.-Gebieten an Italien. Am 28. März

nannte er das Trentino, allerdings nur bis zur natürlichen Sprachgrenze

und unter bestimmten wirtschaftlichen und militärischen Bedingungen.

Die Italiener waren mit diesem Angebot nicht zufrieden. Sie forderten

die sofortige Übergabe der Gebiete – und nicht erst bei Kriegsende – und

die strikte Geheimhaltung der laufenden Verhandlungen.5 Am 10. April

1915 legte Italien seine Forderungen auf den Tisch: das Trentino in den

Grenzen von 1810 (nördlich von Bozen, im Etschtal auf der Höhe von

Gargazon, im Eisacktal auf der Höhe von Kollmann-Waidbruck, d.i. die

napoleonische Grenze), das Isonzogebiet, das Kanaltal, Görz, Gradiska,

die Inselgruppe Curzona, sowie Triest, das Freihafen und -Stadt werden

sollte.6 Burián ging auf diese Forderungen nicht ein, erklärte sich jedoch

5

6

Richard Schober, Die Tiroler Frage auf der Friedenskonferenz von Saint Germain

(Innsbruck: 1982), S. 49; sowie Ders., „St. Germain und die Teilung Tirols“, in: Klaus

Eisterer und Rolf Steininger (Hrsg.), Die Option. Südtirol zwischen Faschismus und

Nationalsozialismus, Innsbrucker Forschungen zur Zeitgeschichte 5 (Innsbruck: 1989),

S. 33–50.

Fontana, Tirol, S. 431.

�6

Rolf Steininger

am 16. April bereit, die Wasserscheide zwischen Vinschgau und Sulzberg

als Grenze zu Österreich zu akzeptieren.7

Die Entente hatte mehr zu bieten. Schon seit August 1914 gab es entsprechende Kontakte; Italien wurden das Trentino, Triest und Valona

für den Fall eines Kriegseintritts angeboten. Am 4. März 1915, parallel

zu den Forderungen an Österreich-Ungarn, beauftragte der italienische Außenminister Giorgio Sonnino Botschafter Guglielmo Imperiali

in London, der Entente die präzisen Forderungen Italiens vorzulegen.

Dazu gehörte auch Südtirol bis zum Brenner. In London wurden diese

Forderungen akzeptiert, wobei Südtirol als Tauschobjekt für die italienischen Forderungen am Balkan stand, die Russland strikt ablehnte. Der

Londoner „Geheimvertrag“ wurde am 26. April 1915 unterzeichnet, am 23.

Mai überreichte der italienische Botschafter in Wien die Kriegserklärung

seiner Regierung.

Diese Entwicklung entsprach den Wünschen der italienischen

Nationalisten. Der extremste von ihnen mit Blick auf Südtirol war Ettore

Tolomei, der auch heute noch vielfach als „Totengräber Südtirols“ gilt.8

Ein Erbe seines „Werkes“ ist noch heute in jeder Südtiroler Gemeinde

zu sehen: die doppelsprachigen Ortsbezeichnungen. Die endgültige

Inbesitznahme und Italianisierung Südtirols waren die beiden wichtigsten

Anliegen Tolomeis. Die Realisierung dieser beiden Punkte – mit beinahe

allen Mitteln – machte er zu seiner Lebensaufgabe. Wer war dieser Mann?

Tolomei (1865–1952) stammte aus einer italienisch-nationalgesinnten

Familie aus Rovereto. Über seine Mutter kam er bereits in frühester Jugend

in Kontakt mit Südtirol; er verbrachte viel Zeit bei seinen Großeltern in

Glen bei Neumarkt. Auf ähnliche Weise lernte er die Dolomiten bei Cortina

d’Ampezzo kennen, wo Verwandte ein Hotel besaßen. Nach dem Besuch

des Gymnasiums in Rovereto begann er 1883 in Florenz sein Studium der

Geschichte und Geographie. Das zweite Studienjahr verbrachte er in Rom,

7

8

Schober, Tiroler Frage, S. 50.

Vgl. zu Tolomei insgesamt Gisela Framke, „Im Kampf um Südtirol: Ettore Tolomei

(1865–1952) und das Archivio per l’Alto Adige, Köln-Tübingen 1987“, sowie Dies.,

„Ettore Tolomei – ‚Totengräber Südtirols‘ oder ‚patriotischer Märtyrer‘?“ In: Eisterer

und Steininger, Option, S. 71–84.

�1918/1919. Die Teilung Tirols

7

wo er in Verbindung zur nationalistischen „Dante Alighieri-Gesellschaft“

trat. Nach dem Studium war er als Lehrer zunächst in Tunis (1888) tätig,

dann an den italienischen Schulen von Saloniki (ab 1894), Smyrna (1897)

und Kairo (ab 1898). 1901 kehrte er nach Italien zurück und erhielt im

Außenministerium eine Stelle im Generalinspektorat für die italienischen

Schulen im Ausland.

Tolomeis Kampf um den Gewinn Südtirols für Italien begann bereits

im März 1890, als die erste Ausgabe der von ihm initiierten und mitherausgegebenen Wochenschrift „La Nazione Italiana“ erschien. Die selbstgestellte Hauptaufgabe dieses Kampf- und Propagandablattes war die

Popularisierung der nationalen und kulturellen Vorstellungen der „Dante

Alighieri-Gesellschaft“. Außerdem wollte sie insgesamt zur Förderung ihrer

irredentistischen Konzepte im Sinne des aufkommenden Nationalismus

beitragen. Sie war eindeutig als Kampf- und Propagandablatt konzipiert.

Den thematisch breitesten Raum nahmen Aufsätze über die beiden „klassischen Ziele“ des Irredentismus, „Trento e Trieste“, ein. Mehrere Artikel

behandelten aber auch Gebiete in der Levante oder Nordafrika. Sie griffen

damit dem späteren Programm des faschistischen Nationalismus, dem

Traum vom Mittelmeerimperium und der Wiederherstellung der Größe

des Alten Rom, vor.

Die in diesen Jahren entstandene „Naturgrenztheorie“ wurde von

Tolomei begeistert aufgenommen. Bereits in der ersten Nummer der

„Nazione Italiana“ berichtete er darüber und unterstrich seine Artikel

durch kartographische Darstellungen. Für ihn war im „Alto Trentino“, wie

er Südtirol damals noch nannte, das ladinische Element von besonderem

Interesse. Er erkannte damals zwar noch die ethnische Eigenständigkeit der

Ladiner an, hielt aber die Assimilation ihrer Sprache an das Italienische für

eine notwendige Voraussetzung zur Verwirklichung seines Programms. Das

Ladinische betrachtete er als das lateinische Element in Südtirol. Durch eine

Italianisierung der Ladiner hoffte er einen italienisch-ladinischen Keil in das

deutschsprachige Gebiet zu treiben, der die „Re-Italianisierung“ begünstigen würde. Die Deutschsprachigen waren „Eindringlinge“ in italienisches

Gebiet, die nun mit Absorbierung oder Aussiedlung zu rechnen hatten.

Im Dezember 1890 musste die „Nazione Italiana“ aus finanziellen Gründen eingestellt werden. Von dieser ersten journalistischen

�8

Rolf Steininger

Unternehmung Tolomeis sind aber zahlreiche formale und inhaltliche

Züge in die größere Publikation des Archivio per l‘Alto Adige übergegangen.

Das breit angelegte thematische Spektrum, später im Archivio auf Südtirol

beschränkt, umfasste hier wie dort eine Vielfalt an historischen, geographischen, literarischen, kunstgeschichtlichen, toponomastischen, ökonomischen und folkloristischen Beiträgen. Auch kann man bereits in der „Nazione

Italiana“ jenes für Tolomei bezeichnende Argumentationsverfahren feststellen, bei dem ideologische Denkschemata prägend auch auf die mit wissenschaftlichem Anspruch geschriebenen Artikel einwirken.

Der Gründung des Archivio per l‘Alto Adige gingen journalistische

Tätigkeiten Tolomeis bei den Zeitschriften „Giornaletto“ und „Minerva“

voraus, ebenso im Jahre 1904 seine Besteigung des Glockenkarkopfes (auch

Glockenkarkofel) in den Ahrntaler Alpen, den er zur „Vetta d’Italia“ erklärte

(und die er als Erstbesteigung deklarierte, obwohl diese bereits 1895 durch

Fritz Koegel stattgefunden hatte). Die Wahl des Namens entsprach der

„Naturgrenztheorie“ und stattete diese Region mit dem äußeren Anschein

der Italianität aus. Damit setzte Tolomei ein eindeutiges Zeichen für seinen

Kampf um den Gewinn Südtirols für Italien. Das Instrument in diesem

Kampf wurde das Archivio, dessen erste Ausgabe im August 1906 in Glen

bei Neumarkt erschien.

Entsprechend dem Programm des Archivio, das den Anspruch auf

Wissenschaftlichkeit und strengste Objektivität erhob – wobei Anspruch

und Wirklichkeit sehr weit auseinanderklafften –, wollte Tolomei die

„Italianität“ Südtirols beweisen und propagieren. Der Anspruch auf

Wissenschaftlichkeit schien durch die Mitarbeit namhafter Wissenschaftler

aus dem Königreich Italien gewährleistet.

Tolomei selbst meinte, dass der erste Band des Archivio in seiner

Konzeption und Ausstrahlung für die österreichisch-tirolische Öffent

lichkeit einem Machwerk verräterischer Gesinnung gleichkommen müsste.

Er berichtete sogar mit Stolz von deutschen Demonstrationen gegen ihn

und das Archivio in Neumarkt.

Die österreichischen Behörden reagierten zunächst zurückhaltend.

Das entsprach dem toleranten Pressegesetz, ging aber auch auf eine

Fehleinschätzung der politischen Absichten Tolomeis zurück. Das änderte

sich in den folgenden Jahren und führte zu einer Reihe von Prozessen

�1918/1919. Die Teilung Tirols

9

und Verurteilungen, die Tolomei unter dem Schlagwort „Pressekampf

gegen Österreich“ („Battaglia di stampa contro 1‘Austria“) wirkungsvoll

für Propagandazwecke ausnützte. Die Tatsache, dass die vierteljährlich

erscheinende Zeitschrift vor allem in öffentlichen und wissenschaftlichen Bibliotheken auflag, verhalf ihr indirekt zu einem hohen Maß an

Autorität; mit der Zeit erhielt sie sogar den Charakter eines Handbuchs

oder Quellenwerkes. Für die Bevölkerung Italiens war es ab 1914 die einzige

Quelle zur Südtirolfrage.

Tolomei war aber auch in anderer Hinsicht aktiv: Er ließ Flugblätter

mit Angaben über die „wahren“ ethnographischen Verhältnisse in Südtirol

und Postkarten mit kartographischen Darstellungen der Region verbreiten; sein Bericht über die Besteigung der „Vetta d’Italia“ und Listen italianisierter Ortsnamen Südtirols wurden kostenlos an die Abonnenten

des Archivio verschickt. Mitarbeiter der Zeitschrift wurden zu den verschiedensten Kongressen der „Dante Alighieri-Gesellschaf “ und zu den

„Congressi Geografici Italiani“ entsandt. Tolomeis Aktion war durchaus erfolgreich. Die Zeitschrift fand in Italien schon bald die gewünschte

Verbreitung, die von ihm besorgten italienischen Ortsnamen wurden allmählich in Landkarten, Lehrbücher, öffentliche Fahrpläne, Zeitungen

und Zeitschriften aufgenommen. Bis zu Beginn des Ersten Weltkrieges

gelang es Tolomei, das Gebiet zwischen Salurner Klause und Brenner mit

einem Anschein von Italianität zu versehen, der von einem Großteil der

über die lokalen Verhältnisse unkundigen Leserschaft als allgemein verbindlicher Rechtsanspruch aufgefasst wurde. Im Archivio wurden zwar alle

möglichen Themen abgehandelt, aber bestimmte Themenschwerpunkte

kristallisierten sich immer mehr heraus: Neben Beiträgen zur Illustration

der Naturgrenzen – etwa in Form der Wasserscheidentheorie – wurde die

Toponomastik immer wichtiger. Tolomei begriff die toponomastischen

Studien als „Re-Italianisierungswerk“ der angeblich vor nicht allzu langer

Zeit gewaltsam germanisierten Orts- und Flur-, aber auch Familiennamen.

Seit 1915 wurde das Archivio in Rom gedruckt. In den nun verlegten

„Serie di guerra“ lässt sich hinsichtlich des Themenspektrums und des

Mitarbeiterstabs eine signifikante Veränderung feststellen. Den überwiegenden Teil der Beiträge verfaßte Tolomei jetzt selbst. Der wissenschaftliche

Anspruch des Archivio, der besonders durch die Mitarbeit kompetenter

�10

Rolf Steininger

Fachleute gewährleistet werden sollte, erwies sich nun als bloßes Dekor, das

gerade in den Kriegsjahren nur dürftig die rein propagandistische Tendenz

der Zeitschrift zu überdecken vermochte. 1915 verbreitete Tolomei bereits

ausführlich seine Vorstellungen über eine mögliche Annexion Südtirols

und über die in diesem Falle zu treffenden Maßnahmen. Mehrere diesbezügliche Denkschriften gingen an den damaligen Ministerpräsidenten,

an andere Regierungsstellen und verschiedene nationale Vereinigungen.

Für die deutsche Bevölkerung war die Assimilierung vorgesehen, auch der

Gedanke einer eventuellen Aussiedlung tauchte bereits auf. Im ArchivioBand 11 von 1916 veröffentlichte Tolomei dann sein erstes „Prontuario dei

nomi locali dell‘Alto Adige“ mit der Übersetzung von ca. 10.000 Ortsund Flurnamen. Es waren ganz oberflächliche Übersetzungen, oftmals

ohne Kenntnis der etymologischen Bedeutung des deutschen Namens.

Manchmal war der deutschen Bezeichnung lediglich eine italienische

Endung angehängt worden. Ein weiteres Betätigungsfeld der Jahre 1916/17

bildete die Anfertigung von geographischen Karten für das „Istituto De

Agostini“, das die italienische Namensgebung Tolomeis unterstützte. Mit

diesen Karten arbeitete dann die italienische Delegation in Saint Germain.

Die Besetzung Südtirols durch italienische Truppen – nach

Kriegsende! – war für Tolomei ein entscheidender Schritt auf dem Weg

zur „Wiedergewinnung“ Südtirols. Für ihn ging es jetzt darum, die Situation

radikal zu verändern und den Südtirolern zu zeigen, dass ihr Land endgültig italienischer Besitz war. Bereits im Oktober 1918 wurde in Rom

das „Büro für die Behandlung des Cisalpinen Deutschtums“ eingerichtet.

Dass Ministerpräsident Vittorio Orlando den Gedanken Tolomeis nicht

so furchtbar weit entfernt stand, macht die Tatsache deutlich, dass er dieses

Büro im November als „Kommissariat für die Sprache und Kultur des

Oberetsch“ nach Bozen verlegte und Tolomei zum Leiter dieser Institution

ernannte. Für sein Kommissariat konnte Tolomei einige Räume des Bozner

Stadtmuseums requirieren.9

Die Aufgabe des Kommissariats fasste Tolomeis Mitstreiter Adriano

Colocci-Vespucci in seinem Tagebuch in einem Satz zusammen: „Der

9

Framke, Kampf, S. 91.

�1918/1919. Die Teilung Tirols

11

Zweck des Kommissariats war die Durchdringung der Italianität beim

ersten Zusammentreffen mit der Bevölkerung.“10 Nach Meinung Tolomeis

durfte es „keine Art von cisalpiner deutscher Autonomie“ geben: „Das

Alto Adige muß ein unlösbarer Bestandteil der Venezia Tridentina bleiben.“ Um dies zu erreichen, hieß es in einem Sofortprogramm „Sofortige

Erlassung von Regierungsdirektiven über die Behandlung des cisalpinen

Deutschtums – keine Gewalttätigkeit, aber auch keine Schwäche, dem

gemischtsprachigen Gebiet Stempel der Italianität aufprägen!“11 Dem

Militärgouverneur Giuglièmo Pecori-Giraldi wurde Mitte November

1918 eine Liste mit 22 Südtiroler Persönlichkeiten überreicht. Diese politisch „gefährlichen“ Elemente sollten zwangsweise entfernt oder interniert

werden. Was diese Liste betraf, so stellte Pecori-Giraldi später lakonisch fest:

„Die Maßnahme der Internierung haben wir in einem einzigen Fall angewandt […]. Wir gingen vom Grundsatz aus, dass wir keine Märtyrer schaffen wollten.“12 Auch bei den anderen Punkten konnten sich Tolomei und

sein Kommissariat nicht durchsetzen. Der Militärgouverneur hatte andere

Vorstellungen von italienischer Politik in Südtirol, und von der Regierung

in Rom kam mit Blick auf die laufenden Friedensverhandlungen in Paris

ebenfalls keine ausreichende Unterstützung für Tolomei. So beschränkte

sich die Tätigkeit des Kommissariats hauptsächlich auf provokatorische

Demonstrationen gegenüber den Südtirolern.13 Neben Pecori-Giraldi

war der Generalsekretär des Amtes für Zivilangelegenheiten beim italienischen Oberkommando, General Agostino D’Adamo, einer der hartnäckigsten Gegner des Kommissariats. Er wollte es sogar auflösen lassen,

was ihm allerdings nicht gelang. Immerhin konnte er durchsetzen, dass das

Oberkommando die Verlegung des Kommissariats nach Trient veranlasste.14

Colocci-Vespucci schrieb entsetzt in sein Tagebuch: „Die einzige Phase der

10

11

12

13

14

Zit. n. Karl Trafojer, Die innenpolitische Lage in Südtirol 1918–1925 (Wien: 1971),

S. 63f.

Zit. n. Claus Gatterer, Kampf gegen Rom. Bürger, Minderheiten und Autonomien in

Italien (Wien-Frankfurt-Zürich: 1968), S. 296.

Ders., Aufsätze und Reden (Bozen: 1993), S. 125.

Framke, Kampf, S. 91.

Vgl. Schober, Tiroler Frage, S. 186.

�12

Rolf Steininger

Italianität bis jetzt ist dieses Kommissariat, das Ettore Tolomei […] hier

heroben errichtet hat, und D’Adamo will es auslöschen!“15

Nach heftigem Protest Tolomeis bei Außenminister Giorgio Sonnino

hob die Regierung die Entscheidung des Oberkommandos am 18. Dezember

1918 wieder auf. Damit wurde das Kommissariat zwar gerettet, aber es blieb

in seiner Arbeit auch weiterhin ziemlich erfolglos. Der größte Konflikt

zwischen Militärregierung und Tolomeis Kommissariat entzündete sich

im Bereich der Toponomastik.16 Schon im November 1918 forderte das

Kommissariat von der Militärregierung die sofortige Einführung von italienischen Ortsbezeichnungen in allen Gemeinden und an den Bahnhöfen.17

Dabei stützte es sich auf Tolomeis „Prontuario“. Das Kommissariat wandte

sich auch direkt an die Regierung in Rom und forderte, dass das „Prontuario“

als Grundlage für die Benennung der Ortsnamen in Südtirol verwendet

werden sollte. Diese Forderung wurde in Rom nicht nur abgewiesen, die

Regierung hielt auch weiterhin an den deutschen Bezeichnungen fest.

So waren in den von der Staatsbahn am 20. November 1918 veröffentlichten Fahrplänen die Namen aller Bahnhöfe Südtirols in deutscher

Sprache abgedruckt.18 Auch in den von Pecori-Giraldi später erlassenen

Manifesten wurden im Unterschied zum ersten Erlass vom 18. November

deutsche Ortsbezeichnungen verwendet. Pecori-Giraldi rechtfertigte seinen

Widerstand mit dem Hinweis, dass „unverantwortliche Elemente, gedeckt

durch den Namen, das Prestige und die Stärke des Heeres“ auf dem Gebiet

der Toponomastik nicht vollendete Tatsachen schaffen könnten, die dem

„Ansehen Italiens bei dieser Bevölkerung“ nur geschadet hätten.19 Verärgert

fuhr Colocci-Vespucci mit zwei Soldaten die Bahnlinie entlang, um die

deutschen Ortsnamen zu überpinseln und durch italienische zu ersetzen,20

die dann von der italienischen Armee wieder entfernt wurden.21

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

Zit. n. ebd.

Gatterer, Kampf, S. 296.

Vgl. Framke, Kampf, S. 92.

Vgl. Trafojer, Lage, S. 67.

Zit. n. Gatterer, Kampf, S. 296.

Vgl. Schober, Tiroler Frage, S. 186.

Vgl. Gatterer, Kampf, S. 296.

�1918/1919. Die Teilung Tirols

13

Auch in drei anderen Bereichen, die später noch eine entscheidende

Rolle spielen sollten, war dem Kommissariat aufgrund der Interventionen

des Oberkommandos kein Erfolg beschieden. Zum einen ging es um die

Gründung einer italienischen Tageszeitung mit dem Namen „Isarco“, zum

anderen um den Versuch, deutsche Ländereien und Realbesitz Italienern

zu übertragen. Das Kommissariat nahm Kontakt mit der italienischen

Hoteliersvereinigung auf, um den Ankauf von Hotels in Südtirol zu forcieren. Im Februar 1919 intervenierte das Comando Supremo, genauso wie bei

dem Versuch des Kommissariats, italienische Schulen in Ortschaften mit

italienischer Bevölkerung einzurichten und die deutschen Schulen in den

ladinischen Tälern in italienische umzuwandeln. Man hatte dafür sogar

schon Lehrkräfte aus ganz Italien gewonnen, die bereit waren, zu diesem

Zweck nach Südtirol zu kommen.22 Colocci-Vespucci schrieb enttäuscht

in sein Tagebuch, Südtirol habe „noch fast nichts von seinem österreichischen Charakter verloren“.23 Erst Ende April 1919, als klar war, dass Südtirol

als Kriegsbeute Italien definitiv zugeschlagen wurde, gab Orlando seine

Zurückhaltung auf. Er genehmigte neue Richtlinien zur Behandlung des

„Germanismo cisalpino“, die unter maßgeblichem Einfluß Tolomeis ausgearbeitet worden waren. Sie sahen u.a. vor:

1.

2.

Entfernung „pangermanistischer“ Persönlichkeiten;

sofortige Errichtung italienischer Schulen gemäß dem Manifest vom

18. November 1918;

3. Einführung der italienischen Nomenklatur;

4. Errichtung der Einheitsprovinz Trient;

5. möglichst weitgehende Unterbrechung der Beziehungen mit Nordtirol.

Wenn von italienischen Nationalisten wie Tolomei die Rede ist, die Südtirol

italianisieren wollten, dann sollten jene Tiroler Nationalisten nicht vergessen werden, die das Trentino germanisieren wollten. Hier ist in erster

Linie der 1905 gegründete „Tiroler Volksbund“ zu nennen, in dem mit

Ausnahme der Sozialdemokraten Vertreter aller Parteien aktiv waren. So

22

23

Vgl. Trafojer, Lage, S. 66.

Zit. n. Gatterer, Kampf. S. 295.

�14

Rolf Steininger

wie für Tolomei die deutschsprachigen Südtiroler keine Deutschen waren,

waren für den Volksbund jene Trentiner, die italienisch sprachen, keine

Italiener. Italianisierte Tolomei die Südtiroler Orts- und Flurnamen, so

wurden jene im Trentino eingedeutscht – aus Riva wurde Reif, Rovereto

zu Rofreit, der Gardasee zum Gartensee usw. Deutschnationale Tiroler

formulierten neue Kriegsziele am „Südabhang der Alpen“, am Rande

der Poebene.24 Man sprach sogar von einer partiellen Aussiedlung der

Trentiner und der Ansiedlung deutscher Soldaten.25 Traurige Berühmtheit

erlangte der Sterzinger Volkstag am 9. Mai 1918 (!), eine Veranstaltung

des Tiroler Volksbundes unter Beteiligung von offiziellen Vertretern aller

bürgerlichen Parteien. Es wurde ein 14-Punkte-Programm verabschiedet, in dem es u.a. hieß: „2. Gegenüber Italien natürliche Grenzen, die

Tirol und Österreich besser schützen und altdeutsche Siedlungen […] an

Österreich gliedern“, mit anderen Worten: die Vorverlegung der Grenze

an die Südspitze des Gardasees und Grenzkorrekturen zur Einbeziehung

deutscher Siedlungsinseln. Weiter wurde gefordert:

4. Deutsche Staatssprache und deutsche Staatsrichtung in Österreich.

[…]

5. Einheit und Unteilbarkeit Tirols von Kufstein bis zur Berner Klause,

schärfste Ablehnung jeglicher Autonomie des südlichen Landesteiles,

des sogenannten Welschtirols.

6. Unnachsichtige Bekämpfung der welschen Irredenta, vor allem

durch Schutz und Förderung des Deutschtums in Südtirol einerseits

und Ausweisung der irredentistischen Elemente andererseits, damit

„Welschtirol“ endlich wieder österreichisches Land werde. […]

9. Besetzung des bischöflichen Stuhles in Trient mit einem Deutschen;

gut-tirolerische, deutschfreundliche Priesterausbildung im Bistum

Trient.

10. Vollständige Umgestaltung des Schulwesens in Welschtirol durch

Einführung des deutschen Sprachunterrichtes als Pflichtfach aller

24

25

Haas, Südtirol, S. 100.

Ebd.

�1918/1919. Die Teilung Tirols

15

Schulen und Pflege tirolisch-vaterländischer und deutschfreundlicher

Gesinnung unter Jugend und Lehrerschaft.26

Ein halbes Jahr später war dieser Traum ausgeträumt. Der Krieg war verloren. In Südtirol und Teilen Nordtirols stand die italienische Armee.

Jetzt ging es nur noch darum, die Einheit des Landes zu retten. Weder

in Innsbruck noch in Bozen konnte oder wollte man sich vorstellen, dass

Südtirol an Italien verlorengehen würde. In Südtirol weigerte man sich

zunächst einfach, die Realitäten nüchtern zu sehen. Der deutschnationale

Bürgermeister von Bozen, Julius Perathoner, lehnte es sogar kategorisch ab,

die Bilder des österreichischen Kaisers aus seinen Amtsräumen zu entfernen.27 Man ignorierte die Italiener einfach und verweigerte auch jede Art

der Zusammenarbeit mit ihnen. Aus „Gründen der nationalen Würde“28

entsandte man z.B. keinen Vertreter an den als beratendes Organ der

Militärregierung eingerichteten Provinzialrat für die „Venezia Tridentina“,

die Bezeichnung für das Trentino und Südtirol. Jede Kontaktaufnahme

wurde gleichgesetzt mit einer Anerkennung der bestehenden Situation

oder gar mit Volksverrat. Wie dies manchmal im täglichen Leben aussah,

beschreibt der von den Italienern aus Südtirol ausgewiesene Eduard ReutNicolussi in seinen Erinnerungen:

Jeder Annäherungsversuch der Italiener wurde abgelehnt. Einladungen der Offiziere

zu Festmählern blieben unbeantwortet. Die Militärbehörde in Bozen kam auf den

Gedanken, sich auf dem Wege der Wohltätigkeit an die Bevölkerung heranzumachen. Für derartige Aktionen hatte der Südtiroler immer eine Schwäche gehabt. Die

Militärmusik veranstaltete im Bozner Stadttheater ein Wohltätigkeitskonzert zugunsten der Stadtarmen. Da war es nun schwer, einen Boykott durchzuhalten. Man fand

einen Ausweg: Einige Bürger kauften noch vor dem Konzert alle Eintrittskarten auf.

Das Konzert selbst blieb unbesucht. So hatten die Armen ihr Geld und die Italiener

keinen politischen Nutzen davon.29

26

27

28

29

Abgedruckt in: Der Tiroler, 12. Mai 1918, S. 1.

Vgl. Leopold Steurer, Südtirol zwischen Rom und Berlin 1919–1939 (Wien-MünchenZürich: 1980), S. 32.

Ebd.

Eduard Reut-Nicolussi, Tirol unterm Beil, München 1928 (engl. Ausgabe, London:

1930; Neudruck Bozen: 1983), S. 27.

�16

Rolf Steininger

Die Rettung des Landes erhoffte man sich von Innsbruck, von

Wien, der Friedenskonferenz und dem von Wilson verkündeten

Selbstbestimmungsrecht.

Am Anfang ließ sich die Sache sogar gut an. Am 4. November

1918 gründeten Vertreter der Tiroler Volkspartei und der Freiheitlichen

Partei Südtirols unter Vorsitz von Julius Perathoner einen Provisorischen

Nationalrat für Deutsch-Südtirol. Dieser Nationalrat gab sogar ein eigenes Amtsblatt heraus und proklamierte am 16. November die „Unteilbare

Republik Südtirol“.30 Im Januar 1919 wurde deutlich, dass diese Politik auf

Illusionen aufgebaut war. Das Comando Supremo löste den Nationalrat am

19. Januar auf. Josef Raffeiner, ein Zeitgenosse jener Ereignisse und von 1945

bis 1947 dann Generalsekretär der Südtiroler Volkspartei (SVP), erklärt

die „verfehlte Politik“ der Südtiroler Führungsschicht teilweise damit, dass

nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg sowohl in Südtirol als auch in Innsbruck und Österreich

unter den gebildeten Schichten zahlreiche Stände waren, die einfach nicht glauben

wollten, dass Südtirol von Nordtirol abgetrennt und mit Italien vereinigt werden

sollte. Man glaubte an das Selbstbestimmungsrecht und an die 14 Punkte Wilsons

und fürchtete, die Sache durch Verhandlungen mit Rom zu kompromittieren. Dieser

Glaube zeugt aber von einer großen Kurzsichtigkeit. Man bedachte zu wenig, dass

Österreich in der Villa Giusti bedingungslos kapituliert hatte und dass das sogenannte

Selbstbestimmungsrecht eine so fragwürdige Angelegenheit ist, über dessen Tragweite

die Großen der Welt auch heute noch nicht einig sind. Zu bemerken ist, dass nach

dem Ersten Weltkrieg in Südtirol bei den Bauern und einfachen Leuten viel mehr

als bei den sogenannten gebildeten Schichten die Auffassung verbreitet war, dass das

Land infolge des verlorenen Krieges unwiderruflich bei Italien verbleiben werde. Es

bestand die Tendenz, alles Heil von Innsbruck und Wien zu erwarten und deshalb

möglichst wenig mit Rom zu verhandeln.31

Dass die Südtiroler die Möglichkeit hatten, eine „Republik DeutschSüdtirol“ auszurufen, ist für den italienischen Historiker und Diplomaten

Mario Toscano der erste Beweis für die Mäßigung und Toleranz der

Militärregierung,32 und die Überlegung dieser „Republik“, Steuern ein-

30

31

32

Vgl. Parteli, Südtirol, S. 8–13.

Zit. n. Trafojer, Lage, S. 28.

Mario Toscano, Storia diplomatica della questione dell’Alto Adige (Bari: 1967), S. 69 f.

�1918/1919. Die Teilung Tirols

17

zuheben und eigene Banknoten und Briefmarken zu drucken – woraus

nach Intervention des italienischen Oberkommandos allerdings nichts

wurde –, ist für Toscanos Kollegen Umberto Corsini die „eigenartigste,

utopistischste und fantastischste“ Willensäußerung der Südtiroler, nicht

von Italien annektiert zu werden.33

Die – letztlich erfolglose – sozialistische Anschlusspolitik der Wiener

Regierung hat den Tiroler Interessen damals wohl entscheidend geschadet. Anschluss an Deutschland und Einheit Tirols waren zwei Dinge,

die nicht miteinander zu vereinbaren waren. Außenminister Otto Bauer

wusste dies sehr wohl, dennoch forcierte er seine Politik. Am Ende hatte

man gar nichts, weder Anschluss noch Einheit Tirols. In Südtirol glaubte

man Ende November 1918 allerdings noch daran, dass der Anschluss

Österreichs an Deutschland die Einheit Tirols sichern werde. Der Anschluss

an Deutschland, so hieß es in der ersten Südtiroler Denkschrift, gelte als das

„höchste Streben“. Als weitere Möglichkeiten wurden genannt Anschluss

ganz Tirols an die Schweiz, eine selbständige Republik Tirol, ein neutrales

Südtirol, Südtirol als Freistaat unter italienischer Herrschaft, und zuletzt

ein autonomes Südtirol als Bestandteil Italiens.34

Anfang 1919 war man einen Schritt weiter. In einer Proklamation

vom 7. Januar 1919 war von einem Anschluss keine Rede mehr, weil dies

„den italienischen strategischen Argumenten für die Brennergrenze in die

Hände“ arbeite: „Der einzig gangbare Weg zur Rettung liegt nunmehr in

der sofortigen Selbständigkeitserklärung des deutschen Teiles von Tirol.“

Die entsprechende Proklamation wurde von einer Generalversammlung

aller Südtiroler Parteien beschlossen, auch wenn die Sozialdemokraten ihre

Zustimmung für den Fall einschränkten, dass die deutsch-österreichische

Südtirolpolitik scheitere.35

Wenn überhaupt die Einheit des Landes zu retten gewesen wäre,

dann durch einen mutigen, entschlossenen Schritt, nämlich die von den

Südtiroler bürgerlichen Parteien geforderte Erklärung eines unabhängigen

33

34

35

Corsini, in: Umberto Corsini und Rudolf Lill, Südtirol 1918–1946, hrsg. v. d.

Autonomen Provinz Bozen-Südtirol (Bozen: 1988), S. 61.

Schober, Tiroler Frage, S. 469.

Ebd., S. 371.

�18

Rolf Steininger

Tirols. Dazu aber waren die Sozialdemokraten mit Blick auf Wien weder

in Bozen noch in Innsbruck bereit. So kam es am 20. Januar 1919 nur zu

einem einstimmigen Beschluss der Tiroler Landesversammlung, in dem

die Rede von der Bereitschaft zu „schwersten Opfern“ war, sollte Südtirol

nicht anders zu retten sein.36 Mit Protestversammlungen, Bittschriften

und Appellen war damals keine Politik zu machen. Aber genau dies blieb

den Südtirolern nur mehr übrig, genauso wie später nach dem Zweiten

Weltkrieg. Ähnlich wie 1946 Unterschriften über den Brenner geschmuggelt

und im April in Innsbruck Bundeskanzler Leopold Figl überreicht wurden,37 wurde ein Memorandum der Südtiroler Bürgermeister an Präsident

Wilson im Februar 1919 vom Schnalstal aus über den 3600 Meter hohen

Similaun in das Ötztal und von dort weiter nach Innsbruck gebracht. In

eindringlichen Worten appellierte man an Wilson:

Es kann, es darf nicht sein, dass man den Namen Tirol nach einer tausendjährigen glänzenden Vergangenheit aus der Geschichte löscht, die freien Söhne dieses

Berglandes unter fremdes Joch zwingt und ihnen ihre Sprache, ihre Art und Kultur

raubt.

Seien Sie unserem Volkstum, unserem Lande der gerechte Richter, und das Volk

von Deutsch-Südtirol wird Ihren Namen von Geschlecht zu Geschlecht vererben

als den des Retters unserer Heimat.38

Wilson entschied aus realpolitischen Überlegungen – manche vermuten

aus Unwissenheit – anders. Seine auf einer Pressekonferenz in Paris abgegebene Erklärung zur Adriafrage am 24. April bestätigte alle Befürchtungen:

Südtirol würde von Italien annektiert werden. In dieser Situation beschloss

die Tiroler Landesversammlung am 3. Mai 1919, Tirol als „neutralen

Freistaat auszurufen, falls nur dadurch die Einheit dieses Gebietes erhalten

bleibt“.39 Zum einen kam diese Erklärung viel zu spät, zum anderen waren

36

37

38

39

Haas, Südtirol 1919, S. 129.

Vgl. hiezu Rolf Steininger, Autonomie oder Selbstbestimmung? Die Südtirolfrage

1945/1946 und das Gruber-De Gasperi-Abkommen (Innsbruck: 1987; Neuauflage:

2006), S. 58–61.

In Faksimile bei Rolf Steininger, Südtirol im 20. Jahrhundert. Vom Leben und

Überleben einer Minderheit (Innsbruck-Wien: 1997), 4. Auflage 2004, S. 264.

Schober, Tiroler Frage, S. 265 u. S. 588.

�1918/1919. Die Teilung Tirols

19

aber auch jetzt die Sozialdemokraten immer noch nicht – mit Rücksicht

auf die Wiener Anschlusspolitik – bereit, diesen Beschluss mitzutragen.

Sie enthielten sich der Stimme. Die Wahlergebnisse in späteren Jahren

waren die Quittung dafür.

In Saint Germain wurde inzwischen nicht verhandelt, sondern diktiert und der österreichischen Delegation am 2. Juni 1919 der erste Teil der

Friedensbedingungen übergeben.

Südtirol würde verloren gehen. Einer der drei Tiroler Vertreter in

Saint Germain, der Christlich-soziale Dr. Franz Schumacher, vor dem

Krieg Kreisgerichtspräsident in Trient, schrieb an die Landesregierung in

Innsbruck:

Was die Gebietsbestimmungen betrifft, wurden wie bei den übrigen Ländern, so

auch bei den Tirolern, die schlimmsten Befürchtungen noch übertroffen. Nicht nur

das ganze Gebiet südlich der Waffenstillstandslinie, wie es jetzt von Italien besetzt

gehalten wird, soll an Italien verloren gehen, sondern auch noch ein Teil des außerhalb

dieser Linie gelegenen Pustertales, das altehrwürdige Innichen, das schwer geprüfte

Sextental, die Gemeinden Vierschach und Winnebach sollen der imperialistischen

Ländergier der Italiener zum Opfer fallen.40

In zwei großen Memoranden vom 10. und 16. Juni 1919 versuchte man

auf österreichischer Seite, noch etwas zu retten. Über Südtirol hieß es da:

Nach so viel Leid und Bangigkeit, die ein heldenhaftes und auch auf seine ruhmreiche Vergangenheit stolzes Volk zu ertragen hatte, schreitet man daran, das Land

Andreas Hofers zu zerstückeln und Südtirol endgültig der Fremdherrschaft zu unterwerfen; man greift sogar auf Gebietsteile, die beim Waffenstillstand der Besatzung

entgangen sind.41

Österreich bot eine Neutralisierung ganz Tirols und die Schleifung aller

Befestigungsanlagen in Südtirol an, forderte gleichzeitig für alle umstrittenen Gebiete eine Volksabstimmung. Alles war vergeblich. Am 20. Juli

erfolgte die Übergabe der kompletten Fassung der Friedensbedingungen.

40

41

Schober, „St. Germain“, in: Eisterer und Steininger, Option, S. 43.

Ebd., S. 44.

�20

Rolf Steininger

Otto Bauer zog die Konsequenz aus einer gescheiterten Politik und trat

zurück. Auch dies blieb ohne Auswirkungen auf das Schicksal Südtirols.

Die endgültigen Friedensbedingungen vom 2. September 1919 stellten

den Schlußpunkt für Südtirol dar: Ohne Autonomiebestimmungen, ohne

Minderheitenschutz kam das Land zu Italien.

Am 6. September 1919 stimmte die Nationalversammlung in Wien

dem Diktat von St. Germain mit 97 gegen 23 Stimmen zu. Die Tiroler

Abgeordneten beteiligten sich zum Zeichen des Protestes nicht an dieser

Abstimmung. Vier Tage später unterzeichnete Staatskanzler Karl Renner

den Vertrag. Die italienischen Nationalisten, allen voran Tolomei, triumphierten. Tolomei schrieb noch 30 Jahre später voller Genugtuung in

seinen Memoiren:

Keine Zulassung einer Volksabstimmung, keine Garantie […], die Grenze bei der

Vetta! Der wunderbare Erfolg nach Jahrhunderten sollte durch keinen Augenblick

der Schwäche in Paris getrübt werden […]. Finis Austriae, die Irredenta ist zu Ende

[…], es gibt keine Südtirolfrage mehr, Österreich hat unterzeichnet.42

In der Sitzung der österreichischen Nationalversammlung am 6. September

1919 hieß es für die Südtiroler Abgeordneten, Abschied zu nehmen.

Reut-Nicolussi ergriff zum letzten Mal das Wort. Was er sagte, sollte zum

Vermächtnis werden:

Gegenüber diesem Vertrage haben wir mit jeder Fiber unseres Herzens, in Zorn und

Schmerz nur ein Nein! Ein ewiges, unwiderrufliches Nein! (Stürmischer Beifall im

ganzen Haus, in den auch die dicht gefüllten Galerien einstimmen) […]. Es wird

jetzt in Südtirol ein Verzweiflungskampf beginnen, um jeden Bauernhof, um jedes

Stadthaus, um jeden Weingarten. Es wird ein Kampf sein mit allen Waffen des Geistes

und mit allen Mitteln der Politik. Es wird ein Verzweiflungskampf deshalb, weil wir

– eine Viertelmillion Deutscher – gegen vierzig Millionen Italiener stehen, wahrhaft

ein ungleicher Kampf.43

Reut-Nicolussi ahnte, was kommen würde, trotz anderslautender

Versprechungen von Seiten der Italiener. Was der Leiter ihrer Delegation

42

43

Ettore Tolomei, Memorie di vita Rom: 1948, S. 415 ff.

Reut-Nicolussi, Tirol, S. 30.

�1918/1919. Die Teilung Tirols

21

in Paris und Präsident des italienischen Senats, Tommaso Tittoni, am 27.

September 1919 in der römischen Kammer erklärte, dass nämlich Italien

der Gedanke einer Unterdrückung und Entnationalisierung der nationalen Minderheiten vollkommen fernliege, dass Sprache und kulturelle

Einrichtungen geachtet würden, dass in Südtirol niemals ein Polizeiregiment

mit Verfolgungen und Willkürherrschaft eingeführt werde, was König

Viktor Emanuel III. wenig später noch einmal bestätigte,44 das alles hatte

schon bald keine Bedeutung mehr.

Am 24. September 1920 stimmte der Senat in Rom für ein

Annexionsgesetz, mit dem die im Vertrag von Saint Germain Italien zugesprochenen Gebiete mit königlichem Dekret zu festen Bestandteilen des

italienischen Staates erklärt wurden. Am 10. Oktober 1920 trat es in Kraft.45

In Südtirol nannte man dies eine „Schandtat“ vor der Geschichte.46 In

einem Aufruf der Parteien wurde Südtirol als „Opfer des Friedensvertrages“

bezeichnet und auf die Verweigerung des Selbstbestimmungsrechtes hingewiesen. Gleichzeitig äußerte man die Hoffnung auf „nationale Befreiung“.

Die Bevölkerung wurde allerdings aufgefordert, „jede Ungesetzlichkeit zu

vermeiden und mit Ruhe und Würde das Schicksal zu tragen“.47 Zu irgendwelchen Zwischenfällen kam es denn auch nicht. Der Volksbote beschrieb

die im Lande herrschende Stimmung folgendermaßen:

Ungebrochen und unbesiegt standen wir am Ende des schweren Krieges da, da kam

der Pharisäer Wilson und ließ uns meuchlerisch von rückwärts erdolchen. Wochen,

Monate, ja mehr als ein Jahr hatten wir gegen alle Aussicht gehofft und uns an jeden

Strohhalm geklammert […], bis endlich die rauhe Wirklichkeit auch den hoffhungsseligsten Träumer weckte und zeigte, dass wir zwar da und dort Mitleid fanden, aber

nirgends Hilfe.48

44 Zit. n. ebd. S. 38.

45 Luciano Dallago, Liberalismo, Nazionalfascismo e Alto Adige (1918–1923) (Milano:

1971), S. 88

46 Hartwig Falkensteiner, Die italienische Südtirolpolitik von 1918 bis 1922 (Dipl.

Innsbruck: 1995), S. 84.

47 Zit. n. Reut-Nicolussi, Tirol, S. 67 f.

48 Michael Forcher, Geschichte Tirols in Wort und Bild (Innsbruck: 1984), S. 206.

�22

Rolf Steininger

Die Reaktion in Nordtirol war heftiger. Am Tag der Annexion wurde ein

großer „Landestrauertag“ organisiert. Der Schulunterricht entfiel am 9.

Oktober, die Schüler wurden über die Bedeutung des Tages aufgeklärt.

Die Geschäfte blieben geschlossen, in Kinos wurden keine „unwürdigen

Programme“ gezeigt. Am Abend des 9. Oktober läuteten die Kirchenglocken

im ganzen Land, am 10. Oktober gab es Trauersitzungen von Landtag

und Landesregierung, Gemeinderat, Senat der Universität und AndreasHofer-Bund sowie Trauergottesdienste in jeder Gemeinde. Öffentliche

Gebäude und Kirchen waren schwarz beflaggt.49 Mit ohnmächtiger Wut

reagierte die Nordtiroler Presse. In den „Innsbrucker Nachrichten“ hieß es

auf Seite 1: „Und Trauerfahnen wehen …“; im „Tiroler Anzeiger“ hieß es:

„Adler, Tiroler Adler! Nicht verzage!“ Die Artikel waren mit schwarzem

Trauerrand versehen.50

In den darauffolgenden Wochen fanden weitere Trauersitzungen des

Tiroler Landtages, der Tiroler Landesregierung sowie der Gemeinderäte

statt. Am 15. Dezember 1920 schieden die Südtiroler Vertreter aus dem

Tiroler Landtag aus. Ein Jahr später erklärte der Innsbrucker Bürgermeister

Wilhelm Greil in einer außerordentlichen Sitzung des Gemeinderates:

[…] Kein Volk der Erde hat eine so tiefe, innige Heimatliebe wie die Tiroler. Unser

ganzes Volk fühlt es in tiefster Seele, dass Süd- und Nordtirol ein untrennbares

Gebiet ist, welches zusammengehört […]. Wir können ohne Südtirol nicht leben,

und Südtirol nicht ohne Nordtirol.51

Von nun an wurden Jahr für Jahr – nachweislich bis 1936 – jeweils am

10. Oktober, dem „Landestrauertag“, solche Sitzungen mit mehr oder

weniger demselben Programm durchgeführt, jeweils organisiert vom

Andreas-Hofer-Bund. Auch die Presse berichtete immer wieder; ab 1933

49

50

51

Hildegard Haas, Das Südtirolproblem in Nordtirol von 1918–1938, phil. Diss.

(Innsbruck: 1984), S. 29.

Ebd., S. 31.

Vgl. Elisabeth Gasteiger, Innsbruck 1918–1929. Politische Geschichte, phil. Diss. (Masch.)

(Innsbruck: 1986), S. 260.

�1918/1919. Die Teilung Tirols

23

verstummten dann die Berichte über die Annexion vom 10. Oktober mehr

und mehr.52

Die Sozialdemokraten nahmen von Anfang an an diesen

Veranstaltungen nicht teil, weil sie diese deutschnational-völkisch-antiitalienischen und wenig „antifaschistischen“ Demonstrationen nicht für

sinnvoll hielten, insbesondere seit dem „Verrat der Heimwehr“ von 1928.

Dafür entwickelten sie eine eigene, sehr intensive Aktivität in Südtirol: in

ihrer Presse, in Zusammenarbeit mit nach Österreich emigrierten italienischen Antifaschisten (in Innsbruck und Wien), als soziale Hilfe für die aus

Südtirol ausgewiesenen Eisenbahner, Bauarbeiter und Postbeamten usw.

Generalkommissar Luigi Credaro versuchte indessen, die Südtiroler

zu beruhigen:

Sobald als möglich werden die politischen Wahlen ausgeschrieben werden. Die

Regierung und das Parlament werden in gemeinsamer Arbeit mit den politischen

Vertretern die administrative und wirtschaftliche Organisation des Gebietes in Angriff

nehmen […]. Hierbei wird es vornehmste Sorge der Regierung sein, an den lokalen Einrichtungen nichts ohne die Mitwirkung jener Männer zu ändern, die euer

Vertrauen als Vertreter eurer Interessen und Bedürfnisse senden wird […]. Ich wünsche

auf das lebhafteste, dass die neue Ordnung des Gebietes den berechtigten Wünschen

der in einer Atmosphäre der Würde, Arbeit und des gegenseitigen Vertrauens vereinigten tridentinischen Volkstämme, wie wir es bei den Italienern, Ladinern und

Deutschen des benachbarten Kantons Graubünden bewundern, entspreche.53

Credaro konnte noch so schöne Worte finden – das änderte nichts

daran, dass das Vertrauen, das die Südtiroler in ihn gesetzt hatten, bereits

weitgehend geschwunden war. Er hatte am 22. Juli 1920 per Dekret die

Zweisprachigkeit der öffentlichen Aufschriften für Bozen, Meran und

einige Ortschaften des Unterlandes angeordnet und in den deutschen

52

53

Haas, Südtirolproblem, S. 33. Als die Südtirolfrage im Oktober 1960 vor der UNO

in New York behandelt wurde, wurde in Innsbruck erstmals wieder der offiziellen

Annexion Südtirols durch Italien in Großkundgebungen gedacht – mit beabsichtigter Fernwirkung Richtung New York. Vgl. hierzu Rolf Steininger, Südtirol zwischen

Diplomatie und Terror 1947–1969, Band 2, 1960–1962 (Bozen: 1999), S. 232–236

sowie S. 365–371 (Abbildungen).

Zit. n. Trafojer, Lage, S. 204 f.

�24

Rolf Steininger

Sprachinseln südlich von Salurn die deutsche Unterrichtssprache verboten

und die italienische eingeführt. Auch wenn die Sprachenanordnung nicht

befolgt und von Rom auch wieder aufgehoben wurde, Credaro traute man

nicht mehr. Es waren kleine Schritte, die das Gefühl der Ohnmacht und

des Ausgeliefertseins in Südtirol steigerten.

Am 26. Oktober 1920 wurde mit königlichem Dekret die italienische Verfassung auf die neuen Gebiete ausgedehnt. Und mit einem weiteren Dekret vom 30. Dezember 1920 erhielten jene Südtiroler, die vor

dem 24. Mai 1915 in einer Gemeinde gemeldet waren, die italienische

Staatsbürgerschaft. Durch eine im Vertrag von Saint Germain verankerte

Bestimmung erhielten diejenigen, die später zugezogen waren, das Recht

auf Option für die italienische Staatsbürgerschaft. Betroffen davon waren

etwa 30.000 Bewohner, meist Eisenbahn-, Post- oder Gerichtsbeamte und

Lehrer, die zum größten Teil aus anderen Ländern der ehemaligen k. u. k.

Monarchie stammten. Über Annahme oder Ablehnung der Optionsgesuche

entschied eine politische Provinzialbehörde. Trotz gegenteiliger Zusage

wurde die Angelegenheit von italienischer Seite weder rasch noch großzügig bearbeitet. Etwa 10.000 Anträge wurden abgelehnt. Die meisten der

Betroffenen wanderten nach Nordtirol oder in das übrige Österreich aus,

da für ihre Arbeit die italienische Staatsbürgerschaft Voraussetzung war.

Bei den Eisenbahnen verloren bis 1923 90 Prozent der Beamten ihren

Posten. Die entlassenen Beamten wurden sofort durch Italiener ersetzt.

Dadurch schritt die Italianisierung des Bahnpersonals sehr zügig voran. Im

Verkehrsknotenpunkt Franzensfeste beispielsweise bestand bereits Ende

1921 die Hälfte der Bewohner aus Italienern.54