STUDIA CELTICA, XXXV (2001), 213–244

The Place Names of Ancient Hispania and

its Linguistic Layers

JUAN LUIS GARCÍA ALONSO

Universidad de Salamanca

Introduction

In this paper, by offering a case study, I will try to give an impression of the methodology I have already used in a more comprehensive toponymic survey.1 Ptolemy divides

the Peninsula, in agreement with the Roman administrative division of his time (middle of the second century AD), into three provinces, Baetica, Lusitania and Tarraconensis.

One of the aims of my previous study was to provide a survey of the scholarship on the

identification of every place mentioned.2 The great number of place names provided by

Ptolemy’s work is indeed a very valuable source (however troublesome) for the knowledge of the languages spoken in the Iberian Peninsula in Antiquity. Therefore, I made

use of the toponymy in an attempt to draw a map of the languages of ancient Hispania

(see also García Alonso 1992, 1994a–b, 1995b, in press-a–g).

In the first part of my study I followed the text of the Geography (after carrying out

a collation of the manuscripts that confirmed the general unreliability of Müller’s standard edition). I commented on every single name (grouped in paragraphs after Ptolemy’s

own division in ethnic entities). Whenever possible, I tried to offer a linguistic affiliation of the name. Next, I presented the historic and linguistic data we have on each

ethnic group, paying special attention to the information concerning the languages that

may occur in their territory. Finally, together with a map of the land of each group, I

offered a tentative classification of the place names, as well as some conclusions relative

to the linguistic map of the area, referring to the general linguistic map, whenever relevant. Obviously, I cannot give here, in this brief account of my study, more than the

general results. By offering a case study, I will attempt to illustrate what I have done

for the whole of the Peninsula. First, I offer an introductory general description of the

linguistic information of ancient Hispania obtained from the place names. Second, I try

to show what we can learn from the language(s) of a particular area by analysing the

place names given by Ptolemy.

1

’La Geografía de Claudio Ptolomeo y la Península

Ibérica, submitted as a doctoral dissertation at the

University of Salamanca in 1993: García Alonso

1995a.

2

Nevertheless, the publication of the several volumes of the Spanish section of the TIR made sud-

denly obsolete a few of my suggested identifications.

I have tried to solve this and other minor effects of

time in my new updated version soon to appear

(2001) as a special volume of Veleia (Garcia Alonso in

press).

�214

JUAN LUIS GARCÍA ALONSO

Ptolemy’s Geography

The last complete edition of the Geography dates from 1843–5: C. F. A. Nobbe (twice

reprinted, 1966 and 1990). Between 1883 and 1901 K. Müller prepared a new, partial

edition which does not include books 6, 7 and 8. In spite of its age and its many deficiencies, this is the standard edition for the part of the Geography that concerns us. Book

2 deals with the Iberian Peninsula in chapters 4 (Baetica), 5 (Lusitania) and 6

(Tarraconensis). The manuscript tradition of the Geography and all kinds of textual discussions are a basic part of my approach. For a recent summary in English on all this,

see Garcia Alonso in press-c. For a more ample updated treatment of the whole matter, see my forthcoming new edition of the Spanish section of Ptolemy’s Geography (in

press-f).

Ancient Hispania: Languages

In general terms (Hoz 1983a: 351–96), we can expect to find a first division of the

Iberian Peninsula in antiquity into two blocs: the Indo-European and the non-IndoEuropean. The first one would correspond to the centre, north and west, and the second one to the rest, that is, Mediterranean Spain, together with a part of the Basque

Country, the Pyrenees from Navarre to Catalonia, the northern and eastern part of the

Ebro valley and almost all of Andalusia (although its western part was subject to strong

Indo-European influences). Recently, though, a new, somewhat revolutionary approach

has been suggested by F. Villar (2000), according to which there might have been a very

old Indo-European layer, particularly strong in the south.

In the place names of the area traditionally considered Pre-Indo-European we can expect

to find linguistic evidence of the following types:

a) Basque in the Basque Country, Navarre, the Pyrenees and adjacent areas (see

Gorrochategui 1984; García Alonso 1995a).

b) Iberian along the Mediterranean coast from eastern Andalusia up to the French

Rousillon. All this area is very rich in Iberian inscriptions that we can read but not

understand, since we know very little about the Iberian language. Some conclusions,

however, have been drawn from its personal onomastics of which we have large indices

(Untermann 1975; 1997, iii, 1, n. 7; see my 1995a). For our purposes, one of the most

important Iberian elements is Il(t)i- ‘town’, present in a good number of place names

in Hispania. This element has been related (although this is really doubtful) to Basque

iri ‘town’ (cf. Irún, Iruñea): see my 1995a, in press-a.

c) Tartessian or Southwestern in central and western Andalusia, the area attributed

to that civilization in all our sources. In this region we find an indigenous epigraphy

with its own traits and with a writing system genetically related to the Iberian script,

but different from it. For our interests now, this epigraphic area seems to be represented in toponymy by a series of characteristic elements: -ippo, -uba, -igi, -ucci, -urci.

Some of them at least (-ippo and -uba) can be both first and second element in compounds. The presence of some of these elements is very useful for our tentative linguistic classification of the names (see my 1995a, in press-a). However, it is quite a

�THE PLACE NAMES OF ANCIENT HISPANIA AND ITS LINGUISTIC LAYERS

215

different matter to give a detailed interpretation of these elements. Villar (2000) now

has a completely new explanation for them, according to which several of these elements

are to be taken as possible evidence of a very old Indo-European layer in the Iberian

Peninsula, in his view responsible for, among other things, several of the oddities of

Celtiberian (substratum).

In all these areas we can also expect to find names from the Greek, Punic (in Andalusia

in particular) and Latin colonizing powers. We must admit even the possibility of finding pre-Roman Indo-European names (the result of deeper penetrations of IndoEuropean peoples towards the Mediterranean than the Iberian epigraphic testimonies

might lead us to suppose). It would not be unlikely, moreover, that the Iberian language (like, to a lesser extent, Basque and Tartessian) had partially covered other nonIndo-European indigenous languages (whose likely toponymic testimonies will be

impossible for us to detect).

Similarly, we can find pre-Indo-European place names (some of which have been

related to Basque) in Indo-European Hispania. Some of them were already fossilized on

the arrival of the Romans, but others may be a symptom of the survival of some isolated pre-Indo-European nuclei. We can also find Latin names. But, by definition, we

expect the majority of the names to be Indo-European. The problems begin, however,

when we try to divide the toponyms into Celtic and non-Celtic. In Hispania we find,

together with clearly Celtic linguistic remains, other elements that are clearly non-Celtic,

like, for instance, that known abundance of peninsular proper names with initial p(inherited from Indo-European but incompatible with Celtic phonetics). These IndoEuropean pre-Celtic languages had been understood and defined in different ways in

modern research (for a recent summary in English on all this, see my in press-c) until

Krahe (whose work in this field with regard to the Iberian Peninsula was completed by

J. de Hoz in 1963), who developed the elusive concept of Alt-europäisch after discovering something in common in river names of almost every corner of the European continent: a series of common Indo-European roots, with common suffixes and common

phonetic results. These results are incompatible with the phonetics of the historically

known Indo-European linguistic branches of every region. And thanks to this we may

advance a step further in the linguistic division of Indo-European Hispania: previous

labels (‘Ligurian’, ‘Illyrian’, ‘Venetian’, ‘sorotáptico’, etc.) did not include very distinctive phonetic traits except in opposition to Celtic. Besides, every non-Celtic IndoEuropean people and language of the Peninsula was included in them, in a quite

heterogeneous ragbag. But the concept of Alt-europäisch is slightly more specific. As a

result, not all the non-Celtic peninsular material can be included whithin this category.

F. Villar has explained (1991: 460 ff.) very clearly how phonetic traits such as (a) the

preservation or loss of initial and intervocalic p- and (b) the merging together or not of

short a and o inherited from Indo-European, give rise to a division of the Hispanic

Indo-Europeans into three blocs rather than two: Celtic, Alt-europäisch and Lusitanian

(four in his more recent view (2000), taking into account the new ‘meridional-ibero-pirenaico’ layer just mentioned). In any case, I find it impossible to accept the concept of a

linguistic unity over such a vast territory at that period. I prefer to imagine that we are

facing ‘partials of a congeries of other unrecognized incipient Indo-European branches’ (to use E. P. Hamp’s words in a personal communication). This does not go against

�216

JUAN LUIS GARCÍA ALONSO

the fact that there seem to be remnants of the type usually called Alt-europäisch in the

Iberian Peninsula. It is extremely difficult to explain them globally and I doubt whether

we will ever be able to do so satisfactorily. But, for now, I feel it is necessary to point

out the names of Hispania that seem to fit in with that so-called language or languagefamily.

In order to determine what languages were spoken in pre-Roman Indo-European

Hispania we only have two nuclei of texts written in indigenous languages. One is in

Celtiberia. The indigenous language (the knowledge of which advanced enormously

after the discovery, some twenty-five years ago, of the already famous Botorrita3

Bronze(s)) is clearly an archaic variety of continental Celtic. The other nucleus is that

of the Lusitanian indigenous texts. Although they have surprising coincidences with Celtic

(especially in vocabulary), these texts are almost unanimously4 considered pre-Celtic,

though Indo-European. This is the language that we call Lusitanian, which, judging

from the inscriptions known, was used at least throughout a large part of the territory

attributed to the Lusitanians. Lusitanian differs from Celtic in a series of traits that I

will not repeat now (see my 1995a, in press-c), although the most disputed is the preservation of Indo-European initial and intervocalic p.

We face the theoretical distinction of three layers (or four, according to Villar) in the

linguistic materials from Indo-European Hispania: Alt-europäisch, whose traits were mentioned above, Lusitanian, which we have just defined within the limited possibilities available to us, and Celtic, which possesses the very important data from Celtiberian, Gaulish

and the other Continental Celtic dialects (all ancient) as well as the evidence from the

insular Celtic languages in their two branches, Goidelic and Brittonic. However, we must

admit that distinction between these three strata is not always possible, and that these

three groups may not exhaust the number of possible and even probable pre-Roman

Indo-European languages in Hispania. We may have an example of this in Villar’s new

theory (2000), however controversial some conclusions may be.

For the consideration of a particular place name as Celtic, we make use of: (a) its phonetics; (b) its parallels (though these are troublesome); (c) the roots used (a clear Celtic

example is the use of the root *segh-); (d) the suffixes (-ako-s and other related, not exclusively Celtic, or the superlative *-(i)(s)am-o-s); (e) emblematic Celtic elements: -briga (<

IE *-bhrgh-, zero grade of *-bhergh- with a vocalization of the vibrant in -ri- characteristically Celtic), etc.

But besides the Lusitanians and Celtiberians in the Iberian Peninsula, from whom we

have an indigenous epigraphy, there were successive populations in Indo-European

Hispania from whom we have no native texts. We only have personal names. They are

our only direct evidence for the languages spoken in those areas and we have to give

them all due attention, despite the problems that they entail (see Palomar Lapesa 1957;

Untermann 1965; Albertos 1966; Gorrochategui 1984; Evans 1967; Schmidt 1957; or

3

A new bronze was discovered in October 1992 in

Botorrita with a Celtiberian inscription much longer

than that of 1970. After the first excitement, there was

a slight disappointment: the text provides mainly

proper names. However, much new information is

being obtained from these. See Beltrán, De Hoz and

Untermann 1996. But more inscriptions are constantly appearing in this very privileged site. See now

Villar, Díaz, Medrano and Jordán 2001.

4

Untermann and a group of his disciples do not

agree.

�THE PLACE NAMES OF ANCIENT HISPANIA AND ITS LINGUISTIC LAYERS

217

Abascal 1994; to cite just a few examples). Indo-European Hispania, then, can be divided into areas according to the relative frequency of certain personal names in combination with what we know of those two areas.

Proper names become very important when they constitute our only source. However,

we need to bear in mind the danger of building hypotheses that rest solely on them,

since proper names present inherent problems, such as the fact that they are spread far

beyond the spatial and temporal boundaries of the language in which they were created.5

The Names of the Astures as a Case Study

I have chosen the territory of the Astures for several reasons. First, the north-west is a

particularly difficult area and large enough to be a good example of the kind of troubles encountered in undertaking such a study. There are, moreover, many ill-proven

assertions on the Celticity of the north-west (based, for example, on the use of bagpipes)

and it is attractive to have something more serious to account for it. At the same time,

this is a region far enough from the Celtiberian and Lusitanian epigraphic areas to have

any hint from native sources on the languages spoken there: it is in these areas that our

analysis may be most valuable. Finally, let us say that I feel close to the Astures in many

ways, not least of all because they were my ancestors.

Within Indo-European Hispania the language(s) of the people that our sources call

the Astures6 is certainly one of the least well known. They have traditionally been classified, with regard to their language, beside the Gallaici and, together with Lusitani and

Vettones, as belonging to an Indo-European, but not Celtic, ‘Western Bloc’ (Tovar 1961:

91ff.). The Gallaici, given the huge size of their territory (Tovar 1989: 118–19, 125–6)

by the standards of ancient Hispania, and perhaps due to a real ethnic or linguistic difference (Tovar 1989: 115), were subdivided into Gallaici Lucenses and Gallaici Bracari.

The language of the Gallaici Lucenses would be closer to that of the Astures, and that

of the Gallaici Bracari would be particularly close (perhaps even the same according to

some authors like Untermann) to Lusitanian (Tovar 1989: 115), which is known to us

directly, if fragmentarily. The language of the Vettones would also be close to it (García

Alonso 1992, in press-e). Another possibility to be considered is whether the languages

of the Astures and Gallaici belong to the oldest Indo-European linguistic layer in the

Peninsula, pre-dating Lusitanian, as represented by the Alt-europäisch hydronymy. But

there might also be Celtic speakers.7

5

For details about this see my 1995a: 25–8.

Tovar (1989: 103–13) gathers an interesting series

of data and references about them (always put together in our sources with Gallaici, Cantabri and even

Vascones and peoples from the Pyrenees, as far as

their lifestyles are concerned), and their mining

wealth (‘factor determinante en la ocupación romana’,

Tovar 1989: 104).

6

7

Favouring this we have the ancient authors, who

say so explicitly, giving the name of Celtici to several

ethnic groups of the Peninsular NW -and of some

other areas, such as the SW- (Strabo 3. 2.2, 2.15, 3.5;

Pliny 3. 28, 4.111, 4.116, 4.118; Mela 3.10, 3. 13). See

Tovar 1977: iii, 173ff.; Hoz 1988: 194.

�218

JUAN LUIS GARCÍA ALONSO

Paesici [Astures] (2. 6. 5)

Ptolemy attributes them, on the Cantabrian coast, after the Gallaici Lucenses and

before the Cantabri, the town of Φλαουιοναου�α and the river Να�λος.

Φλαουιοναου�α8

TESTIMONIA. Only Ptolemy.

LOCATION.9 Navia, by the river Navia.

ETYMOLOGY. The name Flavia is related by A. Tovar (1989: 369) with ‘las concesiones

que Vespasiano hizo del derecho latino a estas ciudades’, following Hübner.

Navia is frequent as a river name (and as a place name, with examples in the Iberian

Peninsula, France, Britain, Germany and Lithuania: Sevilla 1980: 57–9) and fits well in

the Alt-europäisch hydronymy (Krahe 1949–50: 254–5; Hoz 1963: 236). It could be the

same root we see in Sans. navya, ‘navigable’, Old Persian naviya, ‘fleet’, Greek ν�ϊος ‘concerning a ship’, all from Indo-European *naus, ‘ship’ (Pokorny 1959–69: 755). It is possible to relate this to nava ‘valley’, widely used throughout the Iberian Peninsula

(Corominas 1972; ii. 204) and in other areas of Western Europe (the Dolomitic Alps,

Corsica). The metaphoric use of a word meaning ‘ship’ to designate a valley has parallel examples: Barco in the toponymy of Castille, pointed out by M. Sevilla (1980: 58).

On the other hand, the modern river Navia is cited by A. L. F. Rivet and C. Smith

(1979: 423–4), together with a German river close to Bingen, the Nahe (< Nava), as a

parallel of an ancient British river from which a place on its banks would have got its

name (with an *-io- suffix): Navio, (‘The Roman fort at Brough-on-Noe, Derbyshire’),

according to them from the root *sna-, ‘to flow’ (Holder, 1896–1907: ii. 693–5, has the

same view), from which Welsh nawf, nofio, ‘to swim’ and related to Latin no, nare. We

would then have a hydronymic root (known in Celtic) *Nav- with the meaning ‘water

that flows quickly’, a root that would have survived in the modern British river name

Noe, on whose bank Navio was situated. Navia is almost unanimously considered preCeltic Indo-European (not so by J. Hubschmid, who considers it Celtic (1952), and was

followed by Pokorny), Alt-europäisch in fact. We will place Flavionavia, motivated by a

previous hydronym Navia (the modern river Navia itself or some other) on an Alteuropäisch layer.

Να�λου ποτ. �κβ.

TESTIMONIA. Pliny (4, 111) and perhaps Strabo (8. 4. 20: Μ�λσος).

LOCATION. The Nalón river.

ETYMOLOGY. I wonder whether it would be possible to relate this Nailos (<Na(u)ilos?

– for the loss of that intervocalic -w-, let us remember the possible parallel of the

Lusitanian word oilam, presumably from *owilam, ‘little she-sheep’-) to Navia.10

8

For textual problems see García Alonso in press-

f.

9

For a discussion of this see García Alonso 1995a,

in press-d; TIR.

10

In fact Pokorny (1959–69: 755) includes, under

the root *naus-, some Germanic examples like

Norwegian nola, from *nowilon-, ‘grober Trog, schweres Boot’ and Middle High German noste, ‘Viehtrog,

Wassertrog’, related in his view to the Lithuanian

hydronym Nova and Polish Nawa.

�THE PLACE NAMES OF ANCIENT HISPANIA AND ITS LINGUISTIC LAYERS

219

Astures (2. 6. 28–37)

After quite a long interruption, Ptolemy comes back to the lands of the Astures and

attributes to this people the following inland towns (in 2. 6. 5 he dealt with their towns

on the coast):

Λου^κος ′Αστουρω^ν

TESTIMONIA. Ravennate (4. 42: Luco Astorum).

LOCATION. Traditionally Santa María de Lugo. Perhaps a place near Lugo de Llanera.

There is another very well known Lucus: Lucus Augusti, today Lugo.

ETYMOLOGY. It seems very likely that this is a Celtic name, although we should not

rule out completely the possibility of it being Latin (lucus ‘a sacred grove’, and so Lucus

Augusti ‘a grove (a place?) dedicated to Augustus’). There is a Celtic root *louko- (cf.

Welsh llug and Irish luach <*leuko-; see Holder 1896–1907. ii. 195), ‘shining’, ‘bright’

(cf. Greek λευκ ς; see Sevilla 1980: 52–3), frequent in ancient place names from Hispania

and perhaps to be related to the name of the Celtic god Lug. On the other hand, it

could designate a clearing, or glade in the forest, a possibility supported by the existence of the late Latin word leuco (St Ieronymus In Ioel, III, 18) and its Romance correspondences: French lieu and dialectal Spanish lleco, lieco ‘clearing, glade, treeless

unploughed land’ (even Spanish lugar ‘place’).

There also exists a god name Leucetios, god of the lightning, in Britannia. See Rivet

and Smith (1979: 388) who point out (pp. 388ff.) the names Leuca, Leucarum, Leucomagus

and Leucovia. They mention (pp. 401–2) an ethnic name Lugi (Ptol. 2. 3. 8) and doubt

whether to connect it directly with the god name (with the basic meaning of ‘light’–and

like this word perhaps to be related to the root *leuco-, cf. Old Welsh lleu, Mod. Welsh

goleu and Breton goulou, ‘light’) or to a word meaning ‘black’ (Celtic *lugos> Irish loch,

‘black’) or ‘raven’ (cf. Gaulish lougos, ‘raven’), to which they relate the Asturian ethnic

name Luggonoi mentioned by Ptolemy.

The Latin noun lucus ‘grove’ (related to lux and lucere), with which these place names

have been associated, might be a cognate. I do not believe that these names are Latin:

the peculiar concentration of them in the NW corner of the Peninsula is alone enough

to cause me to prefer the Celtic option.

Ααβερν�ς

TESTIMONIA. Only Ptolemy.

LOCATION. Traditionally Labares (Oviedo).

ETYMOLOGY. F. Diego Santos (1984: 31 and 34) suggests a change in the text. He thinks

that Labernis should be Albernis, very near Puente de Alba (León), where he places the

Pons Albei so reconstructed by him from a couple of names (Fonte Albei and Pons Naviae)

mentioned in the Itineraries. This is all very uncertain, but if he were in fact right, the

name would belong in the same series of names as the modern Alba, with a well-known

element that is used particularly with river and mountain names: Alpes, Albion, Alba. It

is not sure that they all belong to one and the same base; maybe this suggests that there

�220

JUAN LUIS GARCÍA ALONSO

is more than one). There could be as well a connection with the old name of Britain:

Albion, that Rivet and Smith (1979: 248) connect with medieval Welsh elfydd (<*albio-),

‘world’, ‘Earth’, rather than with a Celtic adjective (from IE. *albhos; see Albertos Firmat

1970: 167 who accepts that in some other cases alb- / alp- means ‘altura’) cognate of

Latin albus (Holder 1896-1907, I: 83). *albh- is also one of the roots of the Old European

river name repertoire (Hoz 1963: 231), and so it could also be placed on this stratum,

without us being really able, from a linguistic point of view, to decide in favour of one

or the other group. This name element is present in a series of names from the Iberian

Peninsula (Albocela of the Vaccaei, Albiones of the Astures).

But if we take the place name as it is given in Ptolemy’s text, Labernis, the etymology

of the name is, obviously, different. It could perhaps be related to a personal name

Labar[. . .] from Sorribas, which for Albertos Firmat (1966: 126–7) is probably the same

name seen in Gaulish Labarus, based on the adjective *labaros ‘talkative’, from which also

Welsh llafar ‘speech, language, voice’, Old Irish labar ‘talkative’ and Old Cornish and

Breton lavar ‘word’, forms all derived from the Indo-European root *plab- ‘to talk’

(Pokorny 1959–69: 831). According to Albertos this radical is also found in the

hydronymy, cf. Labara ‘(agua) murmuradora’. The toponymic use of this root, at least

for river names, is therefore fully justified. We may consider whether our Lab-er-n-i-s

may be one more derivation from this radical. It would indeed be more plausible if the

name, as often happens, originated in a hydronym (and from here were transferred to

a place on the river banks). If Labernis were derived from this radical (this being of

course far from certain) we have a sign of Celticity in it: the dropping of an initial p-.

’Ιντεράµνιον

TESTIMONIA. A mansio between Pallantia and Vallata on the road Asturica-Burdigala,

according to the mention in It. Ant. (448. 5 and 458. 7).

LOCATION. The confluence of two rivers (Esla and Bernesga?).

ETYMOLOGY. This name is quite often repeated. There is another place name of the

Astures called Interamnium Flavium (Ptol. 2. 6. 28 and It. Ant. 431. 2) and an Interamnium

of the Vaccaei. Finally there are some Interamnienses cited in an inscription from the

Roman bridge in Alcántara (CIL ii. 760). The place name refers to a place between two

rivers, at their confluence. It seems we must place this toponym in a Latin layer, although

there is some Celtic possibility (see below the other Interamnium of the Astures).

’Αργεντ�ολα

TESTIMONIA. The It. Ant. (423. 4: Argentiolum; also in Itinerario de barro IV (Diego Santos

1959: 257) places it on one of the roads from Asturica to Bracara, between Asturica and

Poetavonium.

LOCATION. A place in the Duerna valley, where we may also locate the ethnic group

Orniaci (whose name is related to that of Val-d-uerna < Val-de-Orna).

ETYMOLOGY. The name seems to be formed on argentum, but it might well be the Celtic

cognate *arg-nto-, *arg-ent- or a form from some other Western Indo-European language

(Sevilla 1980: 31–3). This radical for a place name in a valley famous for its mining

�THE PLACE NAMES OF ANCIENT HISPANIA AND ITS LINGUISTIC LAYERS

221

wealth in precious metals in Roman times is hardly surprising. Nevertheless, this is not

the only possible explanation: the same root *arg- is, with a more primary sense of ‘to

shine’, one of the typical roots in the Old European hydronymic repertoire (Hoz 1963:

233), and it is thus possible to place Argenteola on that layer. Its phonetics makes it a

good candidate for both possibilities (Celtic and Alt-europäisch) equally.

Concerning its possible Celticity, it is pertinent to relate this name to that of a

Celtiberian town: Uxama Argaela. Here we have the same root *arg- ‘shining’ we find in

the noun *argnto-, *argento-, ‘silver’, and we have as well a suffix that reminds us of that

in Argenteola. It is indeed possible that both forms are related to some British place

names with apparently the same kind of suffix: the hydronym Uxela (Ptol. 2. 3. 2; see

Rivet and Smith 1979: 482–4), the name of a fort, Uxela (Ptol. 2. 3. 13) and the names

of two towns, Uxelodunum (Rav. 107. 28) and Uxelum (Ptol. 2. 3. 6).

The place name Argenteola, though it may be in part Latinized,11 might have been created by speakers of a Celtic language. Its final linguistic classification appears (despite

having an easily identified etymology) particularly difficult though, since we cannot deny

that it may also be considered Alt-europäisch. In any case, the Celtic hypothesis appears

to me to be the more convincing.

Λαγκ�ατοι

TESTIMONIA. A town famous for its resistance to Rome (Florus (2. 33. 58), Orosius (6.

21. 10; FHA v. 196) and Dio 53., 25. 8; FHA v 186).

LOCATION. The hill Lance, by Villasabariego (Mansilla de las Mulas, León: TIR K30.

138).

ETYMOLOGY. The form given by Ptolemy, if it is not a mistake of the manuscript tradition, looks like an ethnic name. This may be due to the non-urban lifestyle among

the Astures and may be supported by the mention of tribal (or clan-type) groups (with

no real towns) by Ptolemy only in the case of Astures and Gallaici.

The name may be derived from the name of a weapon: Latino-Celtic lancea / lancia

(> Italian lancia, Spanish and Portuguese lanza, French lance) ‘lance, spear’, a name very

appropriate for a warrior nation: cf. gaisati(i) / γαιζηται ‘warscheinlich pilati, speerträger,

von gaiso-n, air. gai’ (Holder 1896–1907: s.v.). But the ethnic name could also come from

Lancia, as there were other places in Hispania with this Celtic name. We have two Lancias

in central Portugal, Lancia Oppidana and Lancia Transcudana (García Alonso 1992, in

press-e), and a town of the Celtici Baetici called Lancobriga or Laccobriga. Menéndez

Pidal (1952: 84) cites three towns called Langa in the Italian Piedmont and Langasco in

the province of Genoa. He suggests a Ligurian origin. Schmoll (1959: 79) mentions *longos and *lango-, ‘long’ and *lonka, ‘river-bed’, as well as the Gallo-Roman word lanca,

11

Due to the vocalism in arg-ent-. Nevertheless, it

is not necessary to talk of Latinization. The Celtic

form seems to come from *argnto- from where Old

Irish argat, arget (genit. argait, arggait, argit), Brit., Old

Cornish and Breton argant-. The Latin form may

either come from *argnto- or from *argento-. Apart

from the fact that vocalic -n- in some Celtic languages

results in -en- (from those historically known, Goidelic

and Lepontic, while Gallo-Brittonic and Celtiberian

have -an-), there are some forms coming from a root

with e, i. e., coming from *argento-n-. For one or the

other reason we have a series of ancient Celtic names

with an e (see Holder 1896–1907: i. 209–14).

�222

JUAN LUIS GARCÍA ALONSO

‘river-bed’. Nevertheless, he also suggests a Ligurian origin (Sevilla 1980: 49–50 suggests a Gaulish origin; see as well Meyer-Lübke 1949; Pokorny 1959–69: 677; Krahe

1966: 217–18). Albertos Firmat (1966: 128; 1972: 294; 1983: 870) finds several personal names based on this word, perhaps with a toponymic origin: five examples of Lancius

in the area of Lusitani and Vettones. Untermann (1965: 197) cites Lanciq(um) from Santa

María de Trives (Orense).

However, although we might think from these variants that the forms Langa, with a

voiced plosive, and the forms Lanca or Lanc-ia, with a voiceless one, are somehow equivalent, in fact they stem from different roots:

1. The first group from *longos ‘long’; when they show an a in the radical syllable

(*lango-), Villar believes they represent the o grade and that they are, therefore to be

considered Alt-europäisch;12

2. The second group may stem from a *lonka ‘riverbed’, attested in the Gallo-Roman

word lanca ‘riverbed’, probably from the ø grade of the Indo-European root that is,

*lenk- ‘to bend’.

If Lancia comes from a *Ln-k-ia in ø grade, there are no arguments against its Celticity

and several in favour.

Μαλ�ακα

TESTIMONIA. Only Ptolemy.

LOCATION. Uncertain (TIR K-30, s.v.).

ETYMOLOGY. Maliaca may share the adjectival suffix -ka with libiaka (from Libia), uetitanaka13 (*Venditana), uirouiaka (Virovia=Briviesca? García Alonso 1994a) from the

Celtiberian tesserae hospitales. This adjectival suffix -ka is used to obtain adjectives from

place names. Could Maliaca be an adjective in form built on a name such as *Malia, in

the same way as the Autraca of the Vaccaei was formed on the river name that we have

kept as our Odra? If Maliaca were really the right form of the place name, it could be

explained as formed on a personal name such as Malius or Mallius, derived with the

Celtic suffix -akos, much in the same way as the place name Maillac from the South of

France (see on this Menéndez Pidal 1952: 136–7).

F. Diego Santos (1984: 31) suggests that Maliaca (a form influenced by the ancient

name of Málaga, Malaka?) is a corruption of *Saliaca (with not much ground, as there

is no reason to reject Maliaca only because it may seem easier to explain the etymology of *Saliaca). We would again face a place name formed with an adjectival suffix on

a river name, Salia, homonym of the river that separated Astures and Cantabri (Sevilla

1984: 60), probably our Sella. There are some toponymic remains of that river name:

we have Sajambre (<Saliamen) crossed by the river Sella, in León, almost on the border

with Asturias, and, in the documents of the monastery of Sahagún (Sevilla 1984: 31), of

AD 1000, the lands of other Saliamen are mentioned.

We may consider a relationship with the name of the Zamoran area of Sayago, that

12

Although if they represent the ø grade, Celtic

cannot be excluded.

13

Lejeune 1955: 102 suggests reading entanaka.kar

(although in 1983: 19, he goes back to uetitanaka),

something accepted by de Hoz (1988: 203) and

Untermann 1990: 358–9.

�THE PLACE NAMES OF ANCIENT HISPANIA AND ITS LINGUISTIC LAYERS

223

could go back to something like *Saliacum (in fact, in medieval documents, Diego Santos

1984: 32, the area is called Saliaco), a form particularly close to the proposed Saliaca.

Were this right, we would find then in Saliaca a linguistic procedure identical to that

observed in native inscriptions in Celtiberian: the tesserae hospitales. That might be seen

as an important indication that our toponym is a Celtic name that may link the Astures

with the Vettones (Salmantica), the Vaccaei (Autraca) and, finally, even with the

Celtiberians. But we must remember that this suffix, well known in Celtiberian, is the

suffix *-ke/*-ko, very productive in many Indo-European languages, among them Latin,

Greek and, most meaningfully for us now, Lusitanian: in the inscription from Lamas de

Moledo we have the word lamaticom, derived with that suffix from the place name preserved to this day. Therefore, the Celticity or non-Celticity of our name cannot be proved

with this method.

This root in Salia belongs in the Alt-europäisch hydronymy: *sal-, (‘salt’, ‘sea’ and even

‘stream of water’). See Krahe 1951/2: 236–8; 1954: 205, 50; 1962: 291; Hoz 1963: 237.

Martín Sevilla (1984: 66) does not agree. As is often the case with him, here too he

prefers the Celtic hypothesis over the Old European one. He looks for support in the

fact that those river names are found throughout Celtic lands. The problem is that they

are found not only there. It is possible, nevertheless, that the people responsible for the

creation of a place name from an Alt-europäisch river name using our -ka suffix were

Celtic or non-Celtic Indo-Europeans of a Lusitanian type and not those that created the

river name. The name would show traces from two different linguistic layers, as may

have happened too with Salmantica and with Autraca. M. Sevilla (1980: 72) thinks that

the phonetic evolution of Salia > Sella must also be due to speakers of a Celtic language:

he explains that evolution as a result of a vowel inflexion, to be seen in all Western

Romance areas, particularly in the Iberian Peninsula, related by some to the Celtic vowel

infection. This had already been seen and pointed out by Tovar 1955a: 23–4; 1955b:

395–9; 1960: 116. On the same line: González 1952: 39; 1964: 6–7; Corominas 1972. i.

22.

I cannot consider this a definite proof of Celticity.

Γ�για

TESTIMONIA. Only Ptolemy.

LOCATION. The similarity of the name tempts us to see here the ancient name of Gijón,

although Ptolemy places this town in the Southern part of the lands of the Astures (TIR

K30, s.v.). The root may have something to do with the name of the Gigurri, commented below.

ETYMOLOGY. Gigia is corrected more or less convincingly by F. Diego Santos (1984: 32)

into Cigia, and this way it is linked with the river Cea, in the province of León, in whose

neighbourhood the town mentioned by Ptolemy must then have been. There is, in any

case, a river Cega, a tributary to the Duero from the South, coming from the Sierra de

Guadarrama in the province of Segovia (in the neighbourhood of Valleruela de

Sepúlveda) and flowing into the Duero in the province of Valladolid, in Viana de Cega.

If the name was really Cigia (< *Cic-ia?), it might have something to do with the root

of numerous names gathered by Holder (1896–1907: i. 1011–12) and the British place

�224

JUAN LUIS GARCÍA ALONSO

name Cicucium (Rivet and Smith 1979: 307). Holder and Rivet and Smith speak of a

root *cic- or *cico-, seen in OIr. cich ‘pap, breast’, ‘mamelle’, Welsh cig, Corn. chic, Middle

Br. quic (Spanish chicha?).

If the river name Cigia, today Cea, could be related to that series of names, we would

be in front of one more example of the voicing of an intervocalic stop, something relatively frequent in ancient Hispania, especially in the north (Cantabri, Astures) and west

(Lusitani). The phenomenon has been related by some (for instance Tovar) to a Celtic

substratum (through its association with the lenition of medieval Celtic languages). But

this is really doubtful, to say the least. F. Villar (1991: 452–3) rejects it explicitly. This

phenomenon has been observed in different areas of ancient Hispania and has been

interpreted by some authors, like Tovar (1961: 91ff.), as the result of a Celtic lenition

in the Celtic languages of the Peninsula.14

We have not sufficient evidence to assign this place name either to a Celtic layer or

to any other. The derivation with an -ia suffix looks Indo-European and we have some

possible connections between the root of this name and some Celtic names. But nothing is certain.

Β�ργιδον Φλαο�ιον

TESTIMONIA. The It. Ant. (425. 4; 429. 2: 431. 1) on a road from Asturica to Bracara,

Ravennate (320. 10) and an inscription (CIL ii. 4248; see Holder 1896–1907: i: 403)

mentioning a Bergido f(lauiensis).

LOCATION. Villafranca del Bierzo or Cacabelos, in the Bierzo area.

ETYMOLOGY. The name, that may survive in the name of the modern Leonese area

(Schulten 1922ff. v. 195; Tovar 1989: 324; with some minor phonetic problems, though),

has the same Indo-European root (*bhergh) – origin of the Germanic berg or burg cognates (Gothic baurgs) – that we see in the toponymic Celtic element -briga (<*bhrgh-a).

But what is genuinely Celtic there is the vocalic phonetic result -ri- < -r- in -briga

(< *bhrgh-a). And so, with Bergidum (<*bhergh-), we cannot be sure that this place name

should be placed on a Celtic layer. We cannot discard the possibility that one or several pre-Celtic Western Indo-European language(s) of Hispania15 used this toponymic element as well. The phonetics fits well with the Celtic hypothesis, although this is not the

only possibility. However, if it is finally proven that Lusitanian treated the IndoEuropean voiced aspirates as voiceless fricatives,16 we could eliminate a candidate for

Bergidum. But we still have the Old European language(s) and, possibly, other different

groups. Nevertheless, if we eliminate Lusitanian for phonetic reasons (this being uncer-

14

It is too complex problem to be dealt with here.

Let us simply say that we do not need a substratum

to explain a phenomenon that is after all not that

strange (something similar happens for instance with

the voiced stops of post-classical Greek) and even if

we think of a substratum it need not be Celtic. Such

a substratum language might have suffered the same

process: Lusitanian, for instance, seems to have suf-

fered it and we know it was not a Celtic language.

15

A language or languages that would share with

Celtic and with the majority of Indo-European languages the evolution of voiced aspirates to simple

voiced stops: *bhergh- > *berg-.

16

According to the etymology proposed for ifadem,

from the inscription from Cabeço das Fraguas.

�THE PLACE NAMES OF ANCIENT HISPANIA AND ITS LINGUISTIC LAYERS

17

225

18

tain), I believe the Celtic possibility is more attractive than the Old European one.

prefer to place our Bergidum in the Celtic layer.

I

’Ιντεράµνιον Φλαο�ιον

TESTIMONIA. The It. Ant. (429. 3 and 431. 2) in a road from Asturica to Bracara, between

Bergidum and Asturica, 30 miles away from the latter.

LOCATION. Congosto, León (TIR K-29, s.v.).

ETYMOLOGY. It might seem appropriate to consider this place name Latin, although

its frequency in Indo-European Hispania, as pointed out above, might suggest a native

formation, which would be very difficult to prove in any case. It would be interesting

to know whether this Inter-, apparently so Latin (already Holder 1896–1907: ii. 56–7,

points out its existence in historic Celtic languages), is the same we see in Intercatia

(whose second element, -catia, is clearly non-Latin; see below the commentary on this

place name of the Astures Orniaci). With regard to the Old Irish preposition etar, eter

‘between, among’, Thurneysen (1946: 510–11) says:

Taking *enter as the basic form in Celtic, one would expect Ir. éter; accordingly it

would be necessary to assume that the e was shortened in proclitic position [. . .] and

that e spread thence to the stressed forms. Perhaps, however, we should rather postulate an early intermediate stage *inter, attracted by the preposition in-; cp. OW. ithr,

Corn. yntre, Gaul. Inter-ambes ‘inter riuos’ Endlicher’s Gloss.

To me, what seems particularly interesting, besides the possible existence of a Celtic

Inter-, is the Gaulish gloss: isn’t that Inter ambes extraordinarily close to our Inter-amnium? Could we not think that our Hispanic names are partial Latinizations of native

names, very likely Celtic and very close to what we see in Gaulish?

Λεγ�ωνζ' Γερµανικ�

TESTIMONIA. It. Ant. (395, 4) and inscriptions (CIL, ii. 369).

LOCATION. León, built on the camps of the Legio VII Gemina.

ETYMOLOGY. Latin name: we do not have any information about the native language.

17

-briga is exclusively Celtic and -berg well known

in Celtic: it survives in medieval Celtic languages:

Cornish and Breton bern, Welsh bera, translated by

Holder (1896–1907, i: 402) as ‘haufe’. Holder (403–5)

gathers a long series of ancient names, many of which

might be Celtic and from which we may underline

those from Hispania: Bergida (according to Florus 2.

33–4. 12–49 a town of the Cantabri), Bergium (a town

of the Ilergetes, today Berga, according to Livy 34.

21. 1 and Ptol. 2. 6. 67), Bergula (a town of the

Bastetani, today Berja -Almería-, according to Ptol. 2.

6. 60) and Bergusia (a town of the Ilergetes, today

Balaguer –Lérida-, according to Ptol. 2. 6. 67).

18

In all this there is a circular reasoning. The problem with Alt-europäisch is that it is defined only by a

set of linguistic traits that oppose it partially to the

other historically known Indo-European branches.

To begin with, its very existence was suggested (but

not even proved) when it was realized that a series of

very old European river names seemed phonetically

incompatible with the historically known IndoEuropean languages. But with cases like berg- we

have no reason for not seeing the word as Celtic or

Germanic, on a case by case basis, and, in fact this is

why we say that berg is not documented in Old

European.

�226

JUAN LUIS GARCÍA ALONSO

Βριγαικινω^ν Βριγα�κιον

TESTIMONIA. Cited in the ‘vía de la Plata’ (It.Ant. 439, 8, 440. 2; Rav. 4. 45) and by

Florus (2, 33. 55). Traditionally (Hübner, in Tovar 1989: 324; Müller, in his edition;

Holder 1896–1907: i: 349; Bosch Gimpera 1932: 523–4; Tovar 1989: 324) it has been

considered the same town Ptolemy himself calls Βαργιακ�ς and situates in the neighbouring territory of the Vaccaei.

LOCATION. Dehesa de Morales, in Fuentes de Ropel (Zamora: TIR K-30, s.v.).

ETYMOLOGY. Brig-aik-ion looks linguistically transparent. And its consideration as a place

name created by Celtic speakers seems clear due to our old friend briga. Briga is more

frequent as a second element in compounds (Segobriga, Nertobriga, Iuliobriga: see a compilation of place names with -briga in Holder 1896–1907: i: 533), but is also used on its

own and followed by suffixes. Rivet and Smith 1979: 278, say that briga is rare as a first

element in compounds, but it is not when, like here, it is accompanied by suffixes. They

cite several examples, among them our Brigaecium, from *bherg- in zero-grade, with a

clearly Celtic vocalization, followed by the well known suffix -aik-.

From now on Ptolemy does not simply name towns, as he usually does, but ethnic entities and their main nuclei (the same happens with the Gallaici), doubtlessly due to the

fact that this area of the far north-west was not yet completely urbanized.

Βεδουνηνσ�ων Βεδουν�α

TESTIMONIA. Placed on the ‘vía de la Plata’ by the It. Ant. (439. 7). The name of the

ethnic group appears also in inscriptions (CIL, ii. 4965 and EE, viii. 404) and on some

augustal boundary-markers separating their lands from those of the camp of the cohors

IV Gallorum (García y Bellido 1963; Mañanes 1982: 137–41).

LOCATION. San Martín de Torres, near La Bañeza (León: TIR, K-30, s.v.).

ETYMOLOGY. The root seems to relate it to the ethnonym of the Gallaici Lucenses

Βαιδυοι, but it is more likely to be a mere homophone, occurring by chance, given the

little phonic entity of the element. It is even less probable that this Bae- is connected

with the names from the south-west (such as Baetis, etc.).

In an inscription from Bragança (CIL, ii. 2507) we find a personal name Bedunus. In

another inscription (CIL, ii. 2861), from Lara, a name of a woman, Betouna, can be read.

These personal names may be related to Baedunia. In this name we could see something

having to do with Celtic -dunum. What Rivet and Smith (1979: 344) say about the name

of a town of the Durotriges, ∆ουνιον, mentioned by Ptolemy (2. 3. 13) seems relevant:

‘Ptolemy’s form has an apparently intrusive -i- not paralleled elsewhere in records of

dunum names; but compare Ptolemy’s writing of the British Mediolanum with the same

erroneous -ion (-ium), and the same error with the same name twice in Gaul (II, 7, 6;

II, 8, 9).’ Might we have in Baedunia a confirmation of that ‘intrusive’ -i- (which would

not be a mistake, then, but rather a common adjectival derivation)? Might this name

have something to do with Caledonia? In an inscription (CIL, ii. 2788) a variant Betunia

is found, an indication that either the form with -d- is a result of the voicing of inter-

�THE PLACE NAMES OF ANCIENT HISPANIA AND ITS LINGUISTIC LAYERS

227

vocalic voiceless stops alluded to in our comments on Gigia or the form with -t- is an

ultracorrection due to the fact that there was such a process going on.

We have not enough evidence to enable us to make a final decision on the Celticity

of this place name. However, R. Lapesa (1942: 20), following A. Castro and G. Sachs

(1935: 187), supports its Celticity, relating the place name to the modern Bedoña

(Guipúzcoa), Begoña (Vizcaya), Bedoya (Santander) and Bedoja (Coruña), deriving them

all from a Celtic bedus, ‘zanja, arroyo’. Bedus was the ancient name of the river Le Bied,

a tributary of the Loing, see Holder 1896–1907: i. 366.

^ν ’Ιντερκατ�α

’Orniakω

TESTIMONIA AND LOCATION. An Intercatia of the Astures appears in an inscription

(CIL, xiii. 8098; see Tovar 1989: 111), although from the Asturia north of the mountains. It is perhaps the same town or we might be dealing with two different homonymous towns (Ptolemy’s would be in the Duerna valley: TIR, K-29, 61–2). This is a name

also used for a place of the Vaccaei (see Wattenberg 1959: 65).

ETYMOLOGY. The Orniaci (mentioned in CIL, ii. 2633, the famous pact of the Zoelae,

of AD 27 and 152; see Holder 1896–1907: ii. 878), an ethnic group of the Astures, have

a name with a Celtic suffix -iako- or -ako- (see Pedersen 1913: ii. 13; the suffix is also

known in the formation of Gaulish place names: see Dauzat 1946: 239; Russell 1991).

As for the first part of their name, it may be related to the river name Duerna, apparently due to a wrong word division (see Madoz 1845–50: 418; Menéndez Pidal 1952:

58; Hoz 1963; González 1963: 288; Moralejo Laso 1977: 212). The Leonese region

through which the river Duerna flows is called the Val-d-uerna, ‘valley of the Uerna’

(Sp. ‘val-d(e)-Uerna’). This name is derived from an Orna (a suffix -acus on a river name,

which reminds us of the process of creation of place names from river names with a ka suffix, discussed under Maliaca) which is perhaps also in the origin of the ethnonym

Orniaci, a people would be so called because they inhabited on the river banks (see

Menéndez Pidal 1952: 57’; González 1963: 290). This Leonese river and the inscription

of the Zoelae cited above, mentioning a Sempronius Perpetuus Orniacus Zoela, is what makes

us (and previously Schulten: Tovar 1989: 111) place this clan of the Orniaci in the southwest of the lands of the Astures, where the group of the Zoelae is usually placed as well

(to be exact in Tras-os-Montes: see Tovar 1989: 112, citing Hübner and Jorge de

Alarca~o). M. Gómez Moreno places them in the Valduerna (Tovar), which I agree with,

even though Tovar prefers the Asturia north of the mountains (Tovar 1989: 111, 332).

The river Huerna in the province of Oviedo is related by R. Menéndez Pidal (1952:

57–8) and by Martín Sevilla (1980: 62–3) to this *Orna. The name of the Huerna, a tributary of the Lena or the Lena itself in its upper course, appears in medieval documents

as Orna. And the poet Venancio Fortunato (see Sevilla 1980: 62–3), bishop of Poitiers

in the sixth century AD, mentions yet another Orna, probably to be related to some of

the French rivers today called Orne.

The Indo-European root would be *ern-, *orn-, *rn-, ‘to start moving’. Orna would

have meant at the beginning ‘water in motion’ and it has been considered as belonging

in the Old-European hydronymy (Krahe 1949–50: 258; 1953: 105, 119; Hoz 1963: 236;

Sevilla 1980: 62). Nevertheless, the Old European language(s) have the defining

�228

JUAN LUIS GARCÍA ALONSO

phonetic trait of being ‘lenguas /a/’ , as F.Villar (1991: 460–6) calls them, that is, languages in which the Indo-European short a and o have merged together into a (according to the traditional reconstruction, to which F. Villar offers a very attractive alternative

1991: 159–170). In this they behave like the majority of Indo-European languages,

including Germanic. Languages with a and o kept apart are, besides Greek and Latin,

Lusitanian and Celtic, particularly relevant for us now. And so, Orna, from a root *or-,

might not be Alt-europäisch, since it keeps an o where it should show an a. On the other

hand, Orna fulfils all the minimum linguistic requirements to be considered Celtic or

belonging to a language of the Lusitanian type.

With the river name Orna we face, then, a double possibility. However, in the case of

the ethnonym Orniaci, we would have additional reasons to go for the Celtic option due

to a suffix that, as we have seen, is usually considered Celtic (Bosch Gimpera, nevertheless, does not consider this people Celtic: 1944: 151).

ETYMOLOGY. In Intercatia, it is possible to isolate a -katia element which according to

Pokorny (1959–69: 534) would be in the base of Latin catena and Latin casa (<*catia),

originally designating a particular kind of hut. But it is particularly interesting for us

now that the same root would justify the Welsh word cader ‘fort’ and Old Irish cathir

‘town’. If the etymologies suggested by Pokorny are right, we would have a parallel of

singular importance for the interpretation of the Hispanic Intercatias (one or two among

the Astures and another one among the Vaccaei). I feel quite justified in pointing out

the Celtic connection here.

An alternative explanation, less likely, would be to relate -cat-ia to the family of Celtic

*catu-, ‘battle’, ‘combat’, ‘fight’, in the same way as the British ethnonyms in -cat-i, such

as Duno-cati, Ri-cati, Trena-cati, are related by Holder (1896–1907: i. 841) to that root.

On Gaulish Catu- see Evans 1967: 171–5.

There is a long series of names derived from this (Holder 1896–1907: i: 847–62).

Interesting examples are the Irish personal name (with almost exact Welsh and Breton

parallels) Cath-bhuadhach (<*Catu-bodiacos), ‘im kampfe sigreich’; or another Irish personal name Cath-gen, Welsh Catgen (<*Catu-genos ‘schalchtenson’, with numerous

Hispanic counterparts: Catuenus is a personal name particularly frequent in Lusitania

(see Palomar Lapesa 1957: 61–2; Albertos Firmat 1966: 81; 1964: 238; 1972: 27; 1979:

15; Untermann 1965: map 23) and of which Albertos (1979: 15) states: ‘Es posible que

Catuenus sea variante de un no documentado Catugenus, si lo comparamos con las dobles

formas Matugenus/Matuenus, Medugenus/Meiduenus, Matigenus/Matienus, etc.’. See Evans

(1967: 171–5), Pokorny (1959–69: 534) and Schmidt (1957: 167).

Our Intercatia may then, although with caution, be placed on a Celtic layer. Inter- may

be Celtic, too, as seen above in our commentary to Interamnium Flavium.

Λουγγ�νων Παιλ�ντιον

TESTIMONIA. The place name appears only in Ptolemy (Müller believes this is a corruption of Pallantia, something that to Tovar (1989: 341) is ‘imposible aceptar’). The

ethnonym appears as well in Rav. (Tovar, 1989: 110, suggests that the form Lugisonis

(322. 1) ‘debe ser corrupción de Luggones’) and in inscriptions. See Diego Santos 1959:

45–6, 163–6; 1978: 23, 43–5; E. Alarcos Llorach 1961–2: 32–3; García Arias 1977: 227.

�THE PLACE NAMES OF ANCIENT HISPANIA AND ITS LINGUISTIC LAYERS

229

LOCATION. According to Ptolemy, it would be located in the north of the territory of

the Astures (Bosch Gimpera (1932: 113): Pola de Lena; Cortés (Tovar 1989: 341):

Collanzo). E. Alarcos Llorach (1961–2), Schulten (1943: 97), Tovar and Roldán Hervás

(1970–1: 215), and the TIR (K-30, 169) follow this when they suggest the identification

with Beloncio, by Piloña, east of Oviedo. This is not difficult to accept on phonetic

grounds and with B- instead of P-, something relevant for its possible Celticity.

ETYMOLOGY. Were the form with a P- right, it could not be Celtic. But if it was with a

B-, it might be. Even the vacillation might be a hint of its Celticity, being perhaps due

to a lack of phonemic distinction between the voiced and the voiceless bilabial stops (since

the cell of the voiceless is empty) or, which is really the same thing, voiceless allophonic

occurrences of a phoneme simply defined as bilabial stop, not participating in the opposition voiceless/voiced. This is M. Sevilla’s opinion (1980: 36–8 and 1984: 59–60 and 66).

I wonder whether it would be possible to relate this place name to the Indo-European

root *bhel-, ‘to shine’ (Sans. bhala) that appears in the names of Celtic divinities such as

Belenos (Holder 1896–1907: i. 370ff.) or Belinos and Belisama (although we must admit

that there are no known vacillations between b and p in these names), perhaps in relation with place names such as the British Belerium (Rivet and Smith 1979: 266–8) and

the Hispanic Belisarium, cited in Rav. 80. 60 between Astorga and Palencia. We might

even mention here the name of the Celtiberian people called Belli by our sources (Holder

1896–1907: i. 387–8).

LOCATION OF THE ETHNIC NAME: Sevilla (1980: 52) believes that Luggoni has survived in the Asturian hamlet of the district of Siero called Lugones (Tovar (1989: 110)

and Alarcos Llorach (1961–2: 32) also think so). Sevilla suggests a ‘forma ablativo-locativa’ *Luggonis. A. Tovar and E. Alarcos think that in the place name Argadenes, to the

north-east of Infiesto, there survives the name of the subgroup of the Lugones called

ARGANTICAENI. To Tovar, ‘la localización de Lugones, Belancio (Paelontium) y Argadenes,

así como el lugar del hallazgo de la lápida que nos ocupa, permiten señalar la difusión

de los lúgones: paralela a la costa, a la espalda de los pésicos’. The TIR (K-29, 69) has

the group divided into two sections, one north of the mountains in eastern Asturias and

the other south of the mountains in the Duerna valley.

It is really possible that this modern place name from Asturias has something to do

with the name of the Celtic god. But there is something against the identification with

the ancient Luggoni: although the text of the Geography places them to the north of the

lands of the Astures, as pointed out above, we have more reliable sources that place

them close to La Bañeza. M. L. Albertos (1975: 46) is correct to comment ‘la extraña

posición geográfica’ of the Luggones from León, questioning even whether it is the same

ethnic group or a different homonymous one (Tovar 1989: 110). On two augustal boundary marks taken as inscriptions number 142 and 143 by Tomás Mañanes (1982), the

boundaries between the land of the IV Cohors Gallorum and the Civitas Luggonum, in the

same way as inscriptions 136–41 (also Mañanes’s numbers), mark the limits between the

same Cohors and the Civitas Beduniensium. Such inscriptions, found in Santa Colomba de

la Vega (Soto de la Vega, La Bañeza), lead us to see Baedunienses and Luggoni as neighbours and settled close to La Bañeza, as already pointed out in the commentary on

Baedunia. This would go against the identification of Paelontium with Beloncio.

�230

JUAN LUIS GARCÍA ALONSO

ETYMOLOGY OF THE ETHNIC NAMES. It is possible to explain this name as Celtic

(Bosch-Gimpera, to whom the Astures are basically non-Celtic, believes the Luggones are

Celts infiltrated among the Astures 1944: 128); the form would be based on the name

of one of the very few pan-Celtic gods, Lug or Lugus. Rivet and Smith (1979: 401–2)

cite an ethnic name Lugi (Ptolemy 2. 3. 8) and doubt whether to connect it directly with

the God name (with the basic meaning of ‘light’ – and so maybe related to the root

*leuco– cf. Old Welsh lleu, Modern Welsh goleu and Breton goulou, ‘light’) or with a word

meaning ‘black’ (Celtic *lugos> Irish loch, ‘black’) or ‘raven’ (cf. Gaulish lougos, ‘raven’),

to which they also relate the ethnic name of the Astures Luggonoi cited by Ptolemy. It

is also possible to consider the root in Old Irish luige, lugae, verbal noun of tongid ‘he

swears’. See also what was said above about Lucus.

M. Sevilla Rodríguez (1980: 52) says (on Adgonna see Evans 1967: 203–11; Albertos

1966: 279–80):

respecto al segundo elemento -gon-, éste podría ser la forma con grado o del radical

céltico -gen- o -gn- que se encuentra formando composición en antropónimos galos e

hispánicos como Esugenus, Ategnia, Adgonna, etc. (. . .) Este elemento de composición

nominal -gen-, -gon- o -gn- habría tenido un significado de ‘hijo, descendiente de’ en

la formación de patronímicos. El gentilicio Luggoni habría aludido al pueblo portador de tal nombre como ‘hijos de Lugus’.

Although this suggestion is tempting, we would rather expect something like *lug-og(e)n-. In any case, even if Sevilla’s analysis is wrong concerning the second element of

the name, I believe he is right as far as its first part is concerned.

Σαιλινω^ν Ναρδ�νιον

TESTIMONIA AND LOCATION. Roldán Hervás (1970–1: 202–15) reminds us that Mela

(3. 15; see also on this Álvarez 1950) speaks of some Salaeni, inhabitants of the Cantabric

coast, on the border between Astures and Cantabri, by the river Sella, ancient Salia

(Schulten 1955–7: 361) or Saelia whose name must have something to do with theirs

(Tovar 1989: 110 considers this ‘evidente’). If we follow Ptolemy’s Geography, these Salaeni

and the Σαιλινοιϖ could not be the same (similar is Sevilla’s view 1980: 68), since these

are situated to the south of the land of the Astures. The curious thing is that Saelini

would agree better with Saelia, from which our Sella, than Salaeni. In fact, as pointed

out by Tovar (1989: 110), in the inscription CIL, ii. 2599 one T. Caesius Rufus Saelenus

makes a dedication to I.O.M. Candiedioni, ‘en relación con el puerto de Candanedo’,

according to him. The TIR (K-29, 92) suggests the SE of the province of Orense (Sierra

de Candá).

ETYMOLOGY. In any case, it seems that both the forms with Sal- and those with Saelcould be reduced to the same Indo-European root (Old European) *sal-, as we saw with

Maliaca or *Saliaca (this process Salia> Saelia has been compared with the vowel infection typical in the medieval Celtic languages, as commented above). The location of the

Saelini in the southern lands of the Astures, as in Ptolemy, might correspond to the modern Zamoran area of Sayago, which, we already noted, could go back to something like

*Saliacum, a form particularly close to the postulated *Saliaca.

�THE PLACE NAMES OF ANCIENT HISPANIA AND ITS LINGUISTIC LAYERS

231

LOCATION. Of Nardinium little may be said but that if the Saelini lived in southern

Asturia, the traditional identification (Schulten 1943: 98) with Noreña, to the east of

Oviedo, or with Gijón (Bosch-Gimpera 1932: 113), cannot be right. M. L. Albertos

(1984: 44), suggests relating a rare personal name (with no parallels in the Peninsular

pre-Roman anthroponymy) from Soto de Cangas, Norenus, with Noreña, Noriega and

with the river Nora. See also M.L. Albertos (1966: 169ff).

ETYMOLOGY. Holder (1896–1907: ii.: 689) points out Celtic *nar- (Old Irish nár, Gr.

α’ ν�ρ, alb. nér, umbr. nerus, ‘man’) in the ethnonym from Germania Narvali. If -dinion

were a corruption of -dunon, it would mean ‘Men Town’, although we would rather

expect *Narodunon. It could be related to Dinia, a name of a town of the Bodiontici in

Galia Narbonense and to Diniacus, today Digny, depart. Eure-et-Loir, both cited by

Holder (1896–1907: i. 1283–4).

Σουπερατι�ων Πεταυ�νιον

TESTIMONIA. Itinerario de Barro (4, Diego Santos 1959: 257–8), a little reliable source

whose very authenticity may be doubtful, and the It. Ant.(423. 4), on a road from Asturica

(39 miles to the south of it) to Bracara.

LOCATION. Today the identification with an excavated site, close to Rosinos de Vidriales

(Zamora) (Tovar’s view) seems sure (TIR, K-29, 85 places the town in Santibáñez de

Vidriales).

ETYMOLOGY. Schulten (1943: 98) suggests that the name of the tribe may be formed

by Super- plus a river name Ata (unknown), indicating that this people lived over the

river, just as the Celtici Supertamarici lived over the river Tambre. Of Petav-o-n-io-n we

may say that it does not look Celtic, due to its initial p-, although it has an Indo-European

aspect overall.

It would be interesting to consider whether we might rather think of a place name

such as *Pent-auo-n-io-m, to be related to a long list of personal and place names (with

the Indo-European root for the ordinal ‘fifth’ – cf. Latin Quin(c)tus– and apparently

with a non-Celtic treatment of it) from Hispania and the rest of the Continent, recently discussed in detail by F. Villar (1994).

^ν ’Αστο�ρικα Αυ’ γο�στα

’Αµακω

TESTIMONIA. The ethnonym appears only in Ptolemy, the place name not only (It.

Ant. 422, 423, 425, 427, 429, 431, 439, 448, 450; Pliny 3. 3. 28 (Asturica urbe magnifica),

Rav. 320 and the inscription CIL, ii. 365).

LOCATION. Astorga (which keeps the name). It was the capital city of the Astures and

of their Conventus Iuridicus, a Roman town that was the meeting point for several roads

coming from Bracara (‘hasta cuatro’, Tovar 1989: 325), Zaragoza, Tarragona and

Bordeaux, apart from the best known of all, perhaps, the ‘vía de la plata’ (Emerita

Asturicam) which provided an outlet for the mining wealth of the north-west. Astorga is

an eponym of the pre-Roman people in whose territory it was built. It seems there was

not a previous pre-Roman nucleus here, although there were very small nuclei nearby

(see Mañanes 1982: 8, with bibliography). Astorga emerged as a consequence of the wars

�232

JUAN LUIS GARCÍA ALONSO

of Rome (from which Augusta) with Cantabri and Astures. It became an important administrative centre with the mission of keeping an eye on the mining business of the northwest. At the end of the war, during which Astorga was the setting of the Roman

headquarters, it was ‘handed over’ to the natives for them to inhabit it and leave their

small fortresses on the mountains (Florus 2, 33, 46, 54–60). This agrees with a systematic Roman policy of urbanizing the troublesome peoples: the account of the natives

being forced to abandon their dwellings on the highlands and settle on the flatlands is

familiar in ancient authors.

ETYMOLOGY. The name of the Astures and of Asturica has to do with the name of the

river Astura, modern Esla. The present-day river name is generally admitted as the phonetic heir of the ancient one and some midway medieval forms are adduced.

Nevertheless, disagreeing with this, see Corominas 1972: i. 101–2. Another hypothesis

is to make this Esla come from the root *eis-, *-is-, and so make it fit within the Old

European series (Hoz 1963: 234). The Astures lived on its banks, so it is difficult to

determine which name came first, although it is more likely that it was the river name

which motivated the ethnic name.

The etymology of the name is unknown. Holder (1896–1907: i. 249) suggests a ligurisch origin, that is, Indo-European pre-Celtic in the terminology of his time. But he

also points out a possible parallel in Baetic and Italic place names such as Asta, Assta,

Hasta, Astapa, Astigi, Astagi, for which he suggests a relation with Basque asta, ‘roca’, or

aste, ‘principio’. But the most exact parallel is a name in Central Europe, ‘zwischen

Altenberg u. Wördern’, according to Holder: Astura. Eugepii vita Severini 1. 1: ‘In vicina Norici Ripensis et Pannoniorum parvo, quod Asturis dicitur, oppido’. 1. 4: ‘In Asturis’.

It is not to be discarded, though, that it was a group of Astures taken there by the

Roman army.

In the name of the group that inhabited the capital and its surroundings, the Amaci,

the natives of the area forced to people the city, we can see: (1) a Celtic suffix -akos;

Rivet and Smith (1979: 453–4), in relation with a British ethnic name Segontiaci, say that

this adjectival suffix, in an ethnic name, ‘presumably implies “people of” a chieftain

(rather than of a region, as is the case with Cantiaci); or if a divine name is in question,

“devotees of”’; and (2) a root well known in the anthroponymy and in the toponymy

of pre-Roman Spain and Portugal. M. L. Albertos (1984: 39) says that names such as

Ammia (or Amia) or Ammius, based on Amma, ‘una voz infantil para designar a la madre’,

are found six times in the province of León and appear as well in Asturias, Paredes de

Nava (Palencia), Padilla de Duero (Valladolid), Talavera de la Reina, in the province of

Madrid, in that of Cáceres and in the Beira Alta. Amma appears several times in León

and once in Valencia de D. Juan, Villaquejida and Astorga, in the province of Palencia,

in Tras os Montes and in the province of Zamora (an Albocolensis woman). See Albertos

1966: 21ff.; 1979: 136; 1985, s.u.; Untermann 1965: no. 7.

The Astures Amaci might then be ‘the people of Am- (Amma, Ammius, Ammia)’. But this

presents some difficulties: perhaps it is too colloquial a base to be used for an ethnic

name. But it is an attractive possibility.

�THE PLACE NAMES OF ANCIENT HISPANIA AND ITS LINGUISTIC LAYERS

233

Τειβο�ρων Νεµετ�βριγα

TESTIMONIA. The It. Ant. (428, 6) between Praesidio and Forum Gigurrorum. We also

have an inscription from Alberite, in the Rioja, mentioning a Iulia Tibura Natraei f. (EE,

9 n. 307a p. 119; Holder 1896–1907: ii. 1834; Tovar 1989: 113; Albertos 1975: 46.

LOCATION. Trives Viejo, in the upper Sil, near Puebla de Trives (TIR, K-29, 101). Müller

suggests that behind Τειβ- may be Τριβ-, exclusively for the identification with the modern Trives. But the modern place name may be the phonetic result of the old one, even

if this was Tibures. Müller does not include his suggestion in the text.

ETYMOLOGY. As for Nemetobriga – it is seldom so clear that we are confronting a Celtic

name19 – formed with the Celtic nemeton ‘sacred grove’, known in Gaulish, and with

Celtic -briga. There are forms with the same root attested in Britannia (Rivet and Smith

1979: 254–5, 424). Holder 1896–1907: ii. 708ff., prefers to translate neme-to-n as ‘sanctuary’, from the adjective *neme-to-s, ‘sacred’, ‘noble’, known as a personal name.

Therefore, Nemetobriga may be ‘Temple Town’ or ‘Nemetos’s Town’, this being a personal name. He has compiled a long series of names based on this element: Nemetacon,

Nemetavi (a people from Galicia, in whose territory was the town of Ου’ ολ βριγα, Ptol.

2. 6. 40), Nemetes, Nemetiales, Nemeto-cena or -gena, *Nemeto-duro-s, *Nemeto-ialo-s, Nemetona, Nemeto-tacio, Nemeturicus.

Tribures, if this is the right form, also looks Celtic, and Holder (1896–1907: ii. 1913ff.)

relates it to the famous name of the Trev-eri (from a river name Treva, Ptol. 2. 11–12).

There could be a connection with *treb-, ‘to inhabit’, and with the Galician ethnic name

Arrotrebae. But the inscription above may be proof that the correct form of the name is

Tiburi or Tibures.

Γιγουρρω^ν Φ�ρος Γιγουρρω^ν

TESTIMONIA. Pliny (3. 28), the It. Ant. (428. 7) and Rav. (4. 45: Foro Gigurnion).

LOCATION. The area of Valdeorras, judging from an inscription (CIL, ii. 2610) found

there. The modern name may well be ‘Valle de Gigurros’ (Holder 1896–1907: i. 2020–1;

Lapesa 1942: 33). Ptolemy cites a town almost without a name of its own: Forum

19

And so Bosch-Gimpera (1932: 499) considers this

people Celtic, not Astur (?). Bosch-Gimpera considers

the Astures in general non-Celtic, and when he finds,

as in this case, names whose Celticity is clear, he sees

there a group of Celts, that are not really, in his reasoning, Astures. It seems preferable to call all the

inhabitants of the area Astures, with no prejudices.

And if we are able to detect more than one linguistic

layer coexisting in their territory, we should accept

them all as Astures (they could only not be considered ‘plenamente astures’ if it could be proved

beyond any doubt that those Celts were newcomers

from, say, Celtiberia. And even this, I believe, would

pose many problems of definition. How long should

they have been there to avoid being called ‘new-comers?). Why should the pre-Celtic people be more

Astures than the Celts? I think that the only thing we

might say is that the most representative group of the

Astures would be the most numerous one. And to

determine which group is the most numerous we

need to analyse the linguistic materials that we have,

scarce as they may be. And if we find people of Celtic

speech behind a particular name we cannot say: ‘they

are Celts, therefore they are not Astures’, but we

should say ‘among the Astures, as far as the evidence

provided by this name seems to show, there were

some speakers of a Celtic language, i.e., at least some

of the Astures were Celtic’. And it is, as I say, through

this analysis of all the materials (linguistic and, to a

certain extent, also archaeological) that we can determine the relative importance of every linguistic layer.

�234

JUAN LUIS GARCÍA ALONSO

Gigurrorum. Schulten (1943: 95) believes that Calubriga and Forum Gigurrorum would be

the same town with a native and a Roman name respectively. Our town was on the road

from Asturica to Bracara and may be placed in Petín (Estefanía 1960: 30, and Roldán

Hervás 1970–1: 207) or in A Cigarrosa (A Rúa, Orense: TIR, K-29, 58–9).

ETYMOLOGY. It does not look Celtic. A link with the place name Gigia could exist. The

vicinity of the Galician world (in fact, the territory of the Gigurri was in the modern

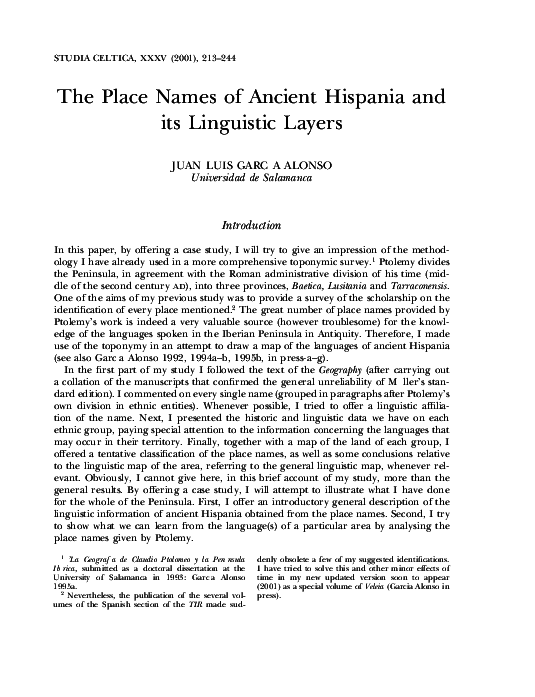

FIGURE 1. Flavionavia 2. Nailus fl. 3. Lucus Asturum 4. Labernis-*Albernis 5. Interamnium

6. Argenteola 7. Lanciati 8. Maliaca-*Saliaca 9. Gigia-*Cigia 10. Bergidum Flavium 11.

Interamnium Flavium 12. Legio VII Gemina 13. Brigaecium 14. Baedunia 15.

Intercatia Orniacorum 16. Paelontium Lungonum 17. Nardinium Saelinorum 18.

Petauonium Superatiorum 19. Asturica Augusta Amacorum 20. Nemetobriga Tiburum

21. Forum Gigurrorum.

�THE PLACE NAMES OF ANCIENT HISPANIA AND ITS LINGUISTIC LAYERS

235

TABLE 1: Tentative Linguistic Classification of the Place Names

Alt-europäisch-type

Alt-europäisch-type with hypothetic

Celtic traces:

Celtic

Other apparently Indo-European:

Pre-Indo-European:

Latin:

Flavio-navia, Naelo ?, Albernis (Celtic??), Super-ati.

Sailini (Celtic infection?).

Lucus (Asturum), Albernis ?, Argenteola ? (these two

might as well be Alt-europäisch), Lancia, Bergidum,

Brigaecium, Orniaci, Intercatia?, Luggoni, Paelontium??,

Amaci, Triburi, Nemetobriga.

Astures (Astura -Alt-europäisch?-, Asturica), Gigia or Cigia

(Celtic?), Baedunia (Celtic?), Nardinium and Petavonium.

Gigurri ?.

Flavio-navia, Interamnium, (Bergidum) Flavium,

Interamnium Flavium, Legio VI Gemina, Super-ati,

(Asturica) Augusta.

province of Orense) is felt in the aspect of the name, somewhat similar to that of the

Seurri, mentioned by Ptolemy (2, 6. 22) among the Gallaici Lucenses. And also referring us back to the world of the Gallaici Bracari is the fact that we find the word Φ ρος

followed by the genitive plural of an ethnic name, doubtless due to the lack of a town

proper, on account of the already mentioned delay of the north-west in urban devel^ν, Φ ρος Λιµιω

^νν, Φορος

opment. Among the Gallaici Bracari we have: Φ ρος Βιβαλω

^ν, 2. 6, 42, 43 and 48 respectively.

Ναρβασω

There is a very risky hypothesis that would relate a hypothetic name element urri to

Basque uri ‘city, town’ (Lapesa 1942: 32). This could also be the case of the ethnonym

Seurri of the Gallaici, their neighbours. But this idea presents many serious problems,

the first and maybe the most important being that this Basque form uri is not clearly

attested in ancient times: the testimony of names such as Pompa-elo (Pamplona) makes

us think that the change -l- > -r- happened probably later, and it just does not seem

possible that ancient names have an element with that form.

This very uncertain theory would place this name on a pre-Indo-European layer and

would be a symptom of a more or less narrow link between the languages spoken in

this region before the coming of the Indo-Europeans and Basque, something that some

scholars have been suspecting for a very long time now (for instance, Lapesa, 1942: 32).

Gigurri could be related to the Gigia given also by Ptolemy. If Diego Santos (see above)

were right and Gigia had survived in the modern river name Cea, could Gigurri then

be based on a place name with an original meaning such as ‘they who live by the river

Gigia’ (the location would not be then by Valdeorras), in the same way as the place name

Autraca of the Vaccaei is ‘the town by the river Autra (> Odra), or the Astures themselves are ‘they who live by the river Astura (Esla)’?.

Conclusions of the Case Study