Social Science & Medicine 120 (2014) 334e343

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Social Science & Medicine

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/socscimed

Rapid response: Email, immediacy, and medical humanitarianism in

Aceh, Indonesia

Jesse Hession Grayman

Nanyang Technological University, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Division of Sociology, 14 Nanyang Drive, HSS-05-26, Singapore 637332,

Singapore

a r t i c l e i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Available online 18 April 2014

After more than 20 years of sporadic separatist insurgency, the Free Aceh Movement and the Indonesian

government signed an internationally brokered peace agreement in August 2005, just eight months after

the Indian Ocean tsunami devastated Aceh’s coastal communities. This article presents a medical humanitarian case study based on ethnographic data I collected while working for a large aid agency in

post-conflict Aceh from 2005 to 2007. In December 2005, the agency faced the first test of its medical and

negotiation capacities to provide psychiatric care to a recently amnestied political prisoner whose erratic

behavior upon returning home led to his re-arrest and detention at a district police station. I juxtapose

two methodological approachesdan ethnographic content analysis of the agency’s email archive and

field-based participant-observationdto recount contrasting narrative versions of the event. I use this

contrast to illustrate and critique the immediacy of the humanitarian imperative that characterizes the

industry. Immediacy is explored as both an urgent moral impulse to assist in a crisis and a form of

mediation that seemingly projects neutral and transparent transmission of content. I argue that the sense

of immediacy afforded by email enacts and amplifies the humanitarian imperative at the cost of

abstracting elite humanitarian actors out of local and moral context. As a result, the management and

mediation of this psychiatric case by email produced a bureaucratic model of care that failed to account

for complex conditions of chronic political and medical instability on the ground.

Ó 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Aceh

Indonesia

Email

Communications

Medical humanitarianism

Narrative

Post-conflict

Psychiatry

1. Introduction

In this article I show how the immediacy of the humanitarian

imperative and the immediacy of email technology conspire to

produce an astonishing set of generative effects and unacknowledged erasures. I start with a description of the humanitarian

context in Aceh and a brief literature review, then provide an account of a medical humanitarian event during the early days of the

International Organization for Migration’s post-conflict reintegration program that challenged the mission’s medical and negotiation

capacities to provide psychiatric care to a recently amnestied political prisoner whose erratic behavior upon returning home led to

his re-arrest and detention at a district police station. This case was

a pivotal moment for the program that illustrated the importance of

medical humanitarian interventions in a post-conflict reintegration

setting, and in particular secured crucial buy-in within the organization for supporting mental health interventions. I reproduce

the history of this event as it unfolded over the course of a few days

E-mail addresses: jgrayman@ntu.edu.sg, jgrayman@gmail.com.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.024

0277-9536/Ó 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

in late 2005 in two comparative but complementary discursive

frames, first in the email archive and then in a more traditional,

thickly described, ethnographic mode of field-based participantobservation. Taken together, the case reveals a set of enduring

double binds that characterize the humanitarian industry (Redfield,

2012), such as the tension between value-rationality, an impulse

toward moral action and advocacy, and instrumental-rationality, an

impulse toward effective program routinization and delivery

(Calhoun, 2008). Other double binds include the differential valuations of technical expertise and local knowledge, the humanitarian agency’s prevailing orientation toward its beneficiaries or its

donors, and the humanitarian figure as effortless mobile sovereign

(Pandolfi, 2003) or caught up in local resistances on the ground.

Frequently these double binds turn upon the distinction between

the expatriates and national staff who work for humanitarian

agencies (Fassin, 2007; Redfield, 2012). In this case study I trace out

the paths by which the immediacy of email amplifies and reinforces

these humanitarian double binds but also renders them invisible to

the IOM staff and their managers who rely most upon this

communication technology to do their jobs.

�J.H. Grayman / Social Science & Medicine 120 (2014) 334e343

1.1. The Indian Ocean tsunami and the immediacy of humanitarian

crisis in Aceh

Aceh is the northwestern-most province of Indonesia on the

island of Sumatra, with the Indian Ocean to its west and the

Malacca Straits along its northeast coast (see Map 1). The capital

city of Aceh province is Banda Aceh, located at the northwestern tip

of Sumatra. On the morning of 26 December 2004, an enormous

earthquake just off the west coast of Aceh unleashed a tsunami

across the Indian Ocean that killed between 130,000 and 180,000

people in Aceh alone and displaced 500,000 more.

The tsunami was not only a natural disaster unprecedented in

recorded human history, it was also a textbook example of how

Peter Redfield defines crisis, a “turning point, a moment of decisive

change, or a condition of instability. a sense of rupture that demands a decisive response” (2005, pp.335e336), compelling and

propelling what is frequently called the “humanitarian imperative.”

In describing a logic of this imperative, Mariella Pandolfi draws

upon the theoretical work of Arjun Appadurai (1996) and Georgio

Agamben (2005) to argue that international humanitarian organizations are driven from one place to the next by what she calls a

“planetary logic” of crisis and exception that legitimizes “supracolonial” intervention with little or no regard for political, institutional, and social actors in anyone location. She calls this “mobile

sovereignty” (Pandolfi, 2003, 2008). Didier Fassin argues that the

humanitarian imperative is now a prevailing form of governmentality built upon and justified through the deployment of

moral sentiments in solidarity with the victims of catastrophe

(Fassin, 2007, 2012; Fassin and Vasquez, 2005). The urgent call to

save lives and alleviate suffering has become institutionalized and

politicized, but the temporality and discourse of urgency that

characterizes the humanitarian imperative lends a veneer of ethical

purity to the endeavor, as if humanitarian interventions stand

outside of politics (Calhoun, 2008, p.91). Within weeks of the

tsunami, hundreds of international and national humanitarian

missions (including several military forces from other nations)

responded to this imperative, arriving in Aceh to assist first with

emergency response and then longer-term recovery efforts.

1.2. Separatist conflict and the chronicity of humanitarian crisis in

Aceh

As thousands of humanitarian workers poured into Aceh, many

learned for the first time about an armed ethno-nationalist

Map 1. Indonesia with Aceh highlighted in Green.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:IndonesiaAceh.png

335

separatist group called GAM, from Gerakan Aceh Merdeka (Free

Aceh Movement), and quickly understood they were in a militarized zone under martial law. Expatriate humanitarians found

themselves housebound by curfews at night and required to travel

by convoy with advance security clearance for every trip outside of

Aceh’s cities. Areas not affected by the tsunami, and especially the

conflict areas called “black zones” in Aceh’s interiors were strictly

off limits.

GAM was first founded in 1976, and Aceh’s densely populated

northern coast was the movement’s ideological heartland and base

of operations (Reid, 2006; Aspinall, 2009). GAM’s founder and

leader Hasan Tiro comes from Pidie district (see Map 2). The event I

highlight in this article took place in the nearby district of Bireuen

to the east of Pidie. The Indonesian military’s first major counterinsurgency operations against GAMdnotoriously recalled for the

disproportionate violence perpetrated against civilian populationsdwere restricted to these north and northeastern districts

throughout the 1990s until shortly after Indonesia’s long-reigning

dictator, President Suharto, resigned in 1998. GAM took advantage of Indonesia’s chaotic period of reform and decentralization to

expand its recruitment across Aceh until May 2003, when the

Indonesian government declared martial law and the military

launched its largest invasion since the occupation of East Timor. For

the next two years, counter-insurgency operations were widespread across Aceh and featured a long list of human rights violations against civilian populations, including spectacular displays of

violence and degrading acts of humiliation (Good et al., 2007).

The military’s counter-insurgency operations against ordinary

Acehnese, even after the tsunami, presented humanitarians with

another kind of crisis in which the everyday violence of conflict had

become thoroughly embedded into Aceh’s social fabric. Aceh’s

prolonged conditions of instability define this crisis more in terms

of chronicity rather than rupture (Vigh, 2008). In these situations,

the normalization of crisis also attenuates the humanitarian

imperative, and the world’s attention to Aceh’s emergency situation before the tsunami went largely unnoticed except among a

select group of human rights activists. Although progress toward a

peace settlement had already been made before the tsunami, the

humanitarian imperative after the tsunami generated the moral

force to complete negotiations and formally conclude hostilities in

August 2005. Dozens of international donors and humanitarian

organizations already working on tsunami recovery in Aceh were

now prepared to assist with humanitarian efforts that would

facilitate the implementation of the peace agreement.

�336

J.H. Grayman / Social Science & Medicine 120 (2014) 334e343

Map 2. Aceh, by Districts (Kabupaten) and Municipalities (Kota). Municipalities include: Banda Aceh, Langsa, Lhokseumawe, Sabang, Subulussalam.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Aceh_Regencies.png

1.3. IOM in Aceh and the immediacy of email in humanitarian

context

At the forefront of post-conflict reintegration and recovery efforts in Aceh was the International Organization for Migration

(IOM), a large inter-governmental organization based in Geneva

with a longstanding tradition of working closely with UN organizations, host governments, and non-governmental organizations.

IOM was in a particularly strategic position to get involved in postconflict recovery in Aceh because the organization already had a

presence there before the tsunami providing support to the Indonesian government with the relocation of communities that were

forcibly displaced from their villages under martial law. Given this

earlier and trusted relationship, IOM was not only able to provide

some of the largest humanitarian assistance after the tsunami, it

was also the first agency that Indonesia’s government relied upon

to discreetly provide transitional reinsertion and reintegration

services to GAM ex-combatants and amnestied prisoners, as well as

to conflict-affected civilian communities. These services included

health care, small transitional cash grants to assist with the initial

reinsertion of amnestied prisoners and former combatants into

their home communities, followed by vocational assistance in the

form of training and in-kind goods. To implement these programs,

IOM quickly opened ten satellite offices across Aceh to support this

work: one in Banda Aceh, four along the northeast coast, two in the

central highlands, and three along the southwest coast. Each office

had a full-time staff of at least eight people responsible for delivering the various components of the program, including one

medical doctor and one nurse.

IOM excels at rapid emergency response, and their logistical

protocol includes establishing and maintaining reliable email

communication networks in sites of natural and man-made

devastation. All of IOM’s offices across Aceh had at least one

desktop computer with a satellite link to IOM’s email servers, and a

generator to keep computers running during Aceh’s frequent power outages. National program officers in Jakarta and senior level

project managers in Aceh carried IOM-issued Blackberry smartphones encrypted with a secure connection to the IOM server so

that they could respond to crisis situations at a moment’s notice

when they are outside the office, underscoring the immediacy of

�J.H. Grayman / Social Science & Medicine 120 (2014) 334e343

the humanitarian imperative that characterizes the industry. These

costly investments guaranteed efficient communications across a

vast and complex humanitarian landscape where tsunamidamaged roads were under repair and inter-city travel required

elaborate security clearances and expensive convoys. The email

network ensured that program managers in Banda Aceh could

reliably coordinate program activities and rapidly circulate documents among their staff in the field.

The most salient and apparent mediation effect that email

technology brings to a humanitarian agency like IOM is its immediacy, enabling all relevant stakeholders in Aceh, Jakarta, and

Geneva to receive and respond to messages at once. In Benedict

Anderson’s Imagined Communities (1991), late colonial era newspaper consumers imagined a community of readers like themselves

sharing the same temporal and spatial experience of readership. In

the 21st century, an imagined community of humanitarians shares

in the immediacy of a temporally instant and seemingly deterritorialized global communication platform because email does not

require a lengthy process of print production and distribution. The

immediacy of email, accessible anywhere and at anytime, admirably performs and amplifies the urgent immediacy of the humanitarian imperative.

But the immediacy of email masks other mediation effects, and

here I refer to William Mazzarella’s definition of immediation, “a

political practice that, in the name of immediacy and transparency,

occludes the potentialities and contingencies embedded in the

mediations that comprise and enable social life” (Mazzarella, 2006,

p.476). Just as the urgency of the humanitarian imperative obscures

the politics of intervention, the immediacy of email projects a

neutral and transparent transmission of content and effaces its

mediating capacity to “transform, translate, distort, and modify the

meaning or the elements they are supposed to carry” (Latour, 2005,

p.39). Building upon insights from the anthropology of documents

and bureaucracy, I argue that the immediacy of email technology is

constitutive of particular bureaucratic rules, ideologies, knowledge,

practices, subjectivities, objects, and outcomes at a humanitarian

agency like IOM (Hull, 2012, p.251).

Despite the recent growth in anthropological studies on new

communication technologies, online communities, and their

mediation effects (Boellstorff, 2010; Engelke, 2010; Gershon, 2010),

my review of the literature shows, with one exception (Skovholt,

2009), no sustained ethnographic account of the structure and

practice of email, much less in conditions of instability where humanitarians work. In the broader social science and professional

literature, discussions about the use of new communication technologies in complex humanitarian emergencies typically focus on

the challenges of information dissemination to the public and coordination among agencies, culminating recently in a report by the

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

titled Humanitarianism in a Network Age (OCHA, 2013), but these

analyses and reviews do not address internal communications and

they rarely mention email.

2. Methods

A content analysis of the IOM email archive offers a novel

methodological point of entry to apprehend the everyday practices

and administration of a large humanitarian agency. The email

archive captures with remarkable fidelity the timeline of IOM’s

activities and negotiations, successes and failures. The archive also

bears witness to the wider context of post-tsunami and postconflict developments in Aceh. News articles and digests, press

releases, research findings, and security incidents all found their

way into my inbox. My archive contains two years (2005e2007) of

content, none of which I ever deleted. To maximize email content

337

from a diversity of sources, I included my email address on all the

internal distribution lists related to IOM’s health and post-conflict

work in Aceh, as well as on distribution lists designated for both

international and national staff. This archival material has been just

as valuable as my own private field notes for reconstructing both

the micro-particularities of my fieldwork in Aceh and the macrohistorical unfolding of the peace process.

This article presents two ethnographic narratives of the same

event, each with their own methodological approach. In the first, I

follow Bruno Latour’s methodological injunction to stick to the

framework and limits indicated by the users themselves (Latour,

1996). My method here is to trace the linked paths of email

threads, one message after the other, delivered through IOM’s email

system, and follow the mediations at every point that effected and

affected the outcomes of a particularly troublesome medical humanitarian event. In short, I produce an ethnographic content

analysis (ECA) among a Latourian “actor-network” of email users.

David Altheide defines ECA as “the reflexive analysis of documents”

(1987, p.65); ECA iteratively draws out themes and trends “reflected

in various modes of information exchange, format, rhythm, and

style” (p.68), and in this case study I use ECA to identify novel

mediation effects that email and its digital infrastructure for

transmission and archivization introduce into social relations. The

second approach relies upon field notes in which I document my

own participation-observations in a subset of the events recounted

below. These two methods and their respective results each provide only partial narratives, but contrasting them highlights the

immediacy of email in humanitarian practice.

As the email exchanges below suggest, this case study served as

a kind of stage-setting device, an event that secured crucial buy-in

within IOM’s Indonesia country mission, marking the beginning of

a lengthy collaborative engagement between IOM, a team of researchers from Harvard Medical School (HMS), Aceh’s mental

health system, and communities recovering from conflict (Good

et al., 2010). IOM first hired me as an intern for their posttsunami health program in summer 2005, then promoted me to

consultant, and later to full time staff, to coordinate a psychosocial

needs assessment in Aceh’s conflict-affected communities. This

assessment was part of a larger five-year IOM-HMS partnership in

which teams of anthropologists, psychiatrists, other doctors, and

students provided technical support to IOM for the development of

post-disaster health interventions in Aceh. All research conducted

under this partnership is protected under an academic freedom

clause. Research proposals were submitted for ethics review and

approved by the Committee for the Use of Human Subjects at the

Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University. I have changed all

names and removed specific characteristics to protect the identities

of the actors involved.

3. A Medical humanitarian encounter by email

In early December 2005, shortly after IOM opened its postconflict field offices across Aceh, Dr. A, the Acehnese IOM doctor

at the Bireuen office, informed the management team in Banda

Aceh about a recently amnestied GAM political prisoner who had

been re-arrested and detained at a local police station due to his

erratic behavior since returning to his rural home. His sister, who

reported his arrest to IOM because he was a beneficiary of the

program, suggested that her brother had a mental illness, and she

asked for Dr. A’s help. I had just moved to Banda Aceh to plan the

upcoming psychosocial needs assessment, so the program managers solicited my input. In what follows I reproduce the case as it

unfolded over IOM’s email network among expatriate and national

staff based in Aceh and Jakarta. In the nine email excerpts quoted

below I occasionally shorten the text but preserve the writer’s

�338

J.H. Grayman / Social Science & Medicine 120 (2014) 334e343

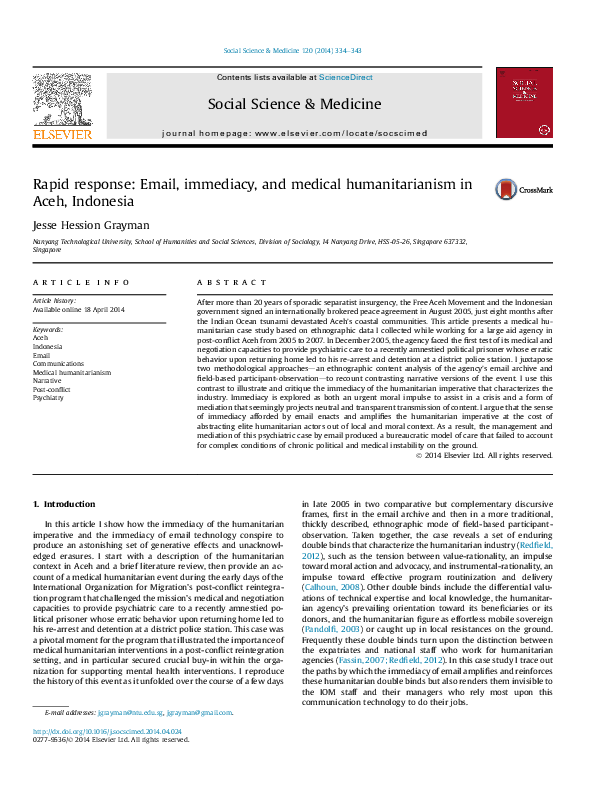

Fig. 1. Organogram of IOM staff with job titles and duty stations.

intent. Fig. 1 provides an organogram of the six IOM staff directly

involved in these email conversations, including their job titles and

duty stations, but a total of 23 peopledin Bireuen, Banda Aceh,

Jakarta, Geneva and Cambridgedwere at least partially included in

a total of 21 emails related to this case that arrived in my inbox over

the course of four office days.

3.1. Dr. E announces the case

Dr. E, the expatriate country director of IOM’s health programs,

sent an evening email from Jakarta to Dr. B, the post-conflict

medical program manager, an Acehnese doctor who worked with

me at our Banda Aceh office. Dr. E cc-ed D, a British specialist in

post-conflict disarmament, demobilization and reintegration programs who was the head of IOM’s Aceh post-conflict operation

based in Banda Aceh. Dr. E also cc-ed several senior managers in

Jakarta, including the Chief of IOM’s Indonesia Country Mission,

suggesting the importance of her message, which had as its subject

line: “One amnestied prisoner with mental illness in Bireuen

prison.”

Dear Dr. B,

Thank you for flagging this situation and for discussing it with

Dr. A in Bireuen. One of our amnestied prisoners named Bayu is

currently in jail because of mental problems. Our initial intake

exam and registration of Bayu in August 2005 when he was

released from prison does indicate Bayu has severe mental

health problems.

In cases such as this, the next of kin becomes the legal guardian

of the patient. We are not able to treat without informed consent from a family member or legal guardian. Can we arrange for

[our part-time psychiatrist] Dr. C to go to Bireuen as soon as

possible for one day to make a proper assessment? IOM will

provide medications. Depending on Dr. C’s diagnosis and plan of

action, we can facilitate the patient’s transfer to the psychiatric

hospital in Banda Aceh, but only if necessary; I’d rather he stay

in Bireuen so family and friends can visit him.

Please send me updates whenever available. Regards, E

3.2. D weighs in

The next morning, D replied immediately with enthusiasm,

addressing his email directly to Dr. E and Dr. B, with a cc to all the

original recipients plus several more post-conflict program managers that reported to him, widening the circle of interest in this

case. D correctly anticipated the question of Bayu’s reinsertion

assistance payments:

From the program perspective we are not in a position to pay the

family the reinsertion assistance, at this stage. We will have to

wait until the psychiatrist’s assessment and suggested treatment. This raises a number of ethical questions for the program

to consider:

If the psychiatrist concludes that the beneficiary is not able to

make informed decisions, for his own good, can we pay the

family? The reinsertion assistance is for the individual. How do

we ascertain that the family will make decisions for the good of

our beneficiary?

Is it ethical for us (an international program) to make decisions

for the beneficiary, in place of his family? If the psychiatric exam

suggests that the beneficiary will, with treatment, be in a position to make informed decisions for his own good, should we

wait to pay the cash benefit?

We will await the medical opinion before we answer the above

questions. My main priority is to get this guy out of prison, it is

not the place for him, and as a beneficiary we have a responsibility to ensure that is achieved.

It is not surprising that Dr. E’s concerns are about treatment and

informed consent, or that D’s concerns are about how the program

proceeds with its cash reinsertion assistance if Bayu is compromised in his ability to make informed decisions. Nevertheless their

concerns talk past each other, and according to the ethical conventions of their respective fields of expertise, their positions on

how to engage with next of kin contradict. What they agreed upon,

at least, was that the psychiatrist Dr. C should go to Bireuen and

�J.H. Grayman / Social Science & Medicine 120 (2014) 334e343

examine Bayu as soon as possible. Offline D and Dr. B asked me to

join Dr. C. A description of our visit appears later in the article in

order to keep us within the discursive frame of the email archive.

Apart from Dr. C and me, none of the other email correspondents

directly witnessed and evaluated the situation in Bireuen.

339

example of the challenges that we are going to face; we need to

address this issue, starting with this individual.

I am not aware of any post-conflict reintegration processes

globally that have taken PTSD seriously; we are going to cut new

ground with this programme.

3.3. Dr. C’s first medical exam report

We returned to Banda Aceh late that night, and the following

day Dr. C sent his psychiatric evaluation to Dr. E with a cc to only the

senior medical staff based in Banda Aceh and me, suggesting he

only felt accountable to the medical team. In his report, Dr. C reviews Bayu’s medical history based upon his clinical interview and

what two police officers and Bayu’s sister told him. Bayu’s sister

described his strange behavior since returning home from prison in

mid-August. In early November, Bayu was caught stealing a cow. In

the evenings, he would walk quietly behind the neighbors’ houses

wearing a backpack, making the community restless. He occasionally threatened his sister and her child with violence; she was

fearful living in the same house with him. The two policemen and

Bayu’s sister all report that a few days prior to our visit, Bayu stole

the village head’s motorbike, who in turn reported Bayu to the

police for arrest. At the bottom of Bayu’s medical history, Dr. C inserts Bayu’s own perspective with one sentence: “He expressed

feelings of sadness and regret.” Dr. C then reports the results of his

psychiatric exam with a list of symptoms and a prescription that

suggest a depressive disorder, but the diagnosis Dr. C reports is

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

3.4. Dr. B’s perspective

Within hours of receiving Dr. C’s report, Dr. B added her questions and feedback in two emails sent only to Dr. E and D. In the

first, she reports: “I asked Dr. C whether Bayu should be in jail or the

psychiatric hospital and he said: ‘There is no need to transfer him to

the hospital. Right now he is a criminal.’ Need your advice.” In the

second email, she offers her opinion:

After hearing from Dr. A, Dr. C, and Jesse, I assume this patient

needs further medication and help from his family who can take

care of him and will manage his money. I don’t think he can hold

the money himself, but his close family will. They can use that

money for his further treatment, start a small business, etc.

[Citing precedent within the program.] If we gave cash to the

family of a schizophrenic in South Aceh, and if we also gave

money to the family of a prisoner who is in jail for corruption,

why should we make an exception for this case? That’s from my

perspective.

3.5. D’s main concern

The next morning D forwarded Dr. B’s consecutive emails with

her considered opinions and shared his thoughts above them in

light of Dr. C’s diagnosis. He sent his message to Dr. E and the Chief

of Mission, with a cc to the Deputy Chief of Mission and the Senior

Project Development Officer. He notably did not include Drs. B or C

in the conversation. All of the recipients are expatriate staff based in

Jakarta with direct access to IOM’s international donors, scaling up

the discourse and raising the stakes:

My main concern is that Bayu has been diagnosed with PTSD,

what are we going to do about this? I have already said this to

the Harvard team: PTSD is likely to be the main challenge to the

programme effectively assisting reintegration. This is the first

3.6. “Sent from my BlackBerry Wireless Device”

The Chief of IOM’s Indonesia country mission replied to all from

his Blackberry with one sentence praising the expertise of IOM’s

national medical team and IOM’s collaboration with Harvard,

effectively giving his blessing to pursue project development that

will create, in his words, “an international best practices model.”

The automatic taglined“Sent from my BlackBerry Wireless Device”dexcuses the brevity of his message, and assures his staff that

he is monitoring the situation as it unfolds.

3.7. My Bireuen report

Shortly afterwards I sent my single-spaced, three-page report

about our Bireuen trip to D and the four doctors E, C, B, and A. I

wrote it as a more polished version of the ethnographic field notes

that I would write for myself, which is to say that it was a thickly

described moment-by-moment account, with explanatory backstories and revelatory interpersonal dynamics. I return to these

local details below, but in the email archive it had little traction

because no one replied to it apart from Dr. E who used it as a

reference for her medical report on Bayu’s case.

3.8. Dr. E’s last word

Dr. E had the last word in this extended conversation about Bayu

when she sent her finalized medical report. Replying to the Chief of

Mission’s encouraging email sent from his Blackberry, she addresses D and includes only senior IOM officers in Jakarta. She informs D she will arrive in Banda Aceh soon, but her priority is to

meet with Doctors B and C, who are “asking for some guidance from

me on how to streamline our PTSD/mental and other general health

cases.” Her attached report on Bayu, she adds, will be used as a

sample case for discussions with the field doctors and nurses,

because: “We will come across similar cases. This is hands-on

training for our team.” In contrast to my dense narrative report,

Dr. E wrote hers in outline form with bullet-point comments. She

incorporated findings not just from Dr. C, but also from Dr. A and

myself, though she generously ascribed Bayu’s psychiatric symptoms originally reported during his amnesty registration in August

to Dr. C. She also changed Bayu’s diagnosis from PTSD only to PTSD

and mild depression. After summarizing our three sets of findings,

she adds three additional comments of her own:

1. Bayu is suffering from a mental problem that is likely the reason

for his odd behavior that disrupted the community.

2. He was arrested and sent to jail because he stole the village

head’s motorbike.

3. Due to his mental illness, Bayu is not supposed to be in jail. He

requires treatment.

In her plan of action, Dr. E writes in bold-faced print: “in Bayu’s

best interest, it is highly suggested that he be transferred to the

psychiatric hospital as soon as possible for at least seven to ten days

of observation and proper treatment, with nearest of kin to give

consent.” She then instructs Dr. C to coordinate Bayu’s referral and

admission to the hospital, while his actual transfer from Bireuen to

�340

J.H. Grayman / Social Science & Medicine 120 (2014) 334e343

Banda Aceh with a family escort will be handled by Doctors B and A

with all medical, transportation, and administrative costs covered

by IOM. Apart from two follow-up exam reports sent by Dr. C over

the next three months, this is the last we hear of Bayu in the email

archive.

we can partly blame the IOM management team turning their

collective online attention away from Bireuen and toward Jakarta in

the email archive, but now we also have to step outside the inbox to

find out how a different set of actors offline conspired to keep Bayu

in jail.

3.9. Inboxes and black boxes

4. A medical humanitarian encounter offline

Before we look offline to see what happened to Bayu in Bireuen,

we can already see the extent to which IOM’s email network

structures the work environment, reproduces organizational hierarchy, and mediates decision-making processes for its employees.

The overall flow of communication moves up the organizational

hierarchy to IOM’s expatriate officers in Jakarta as the conversation

moves away from the professional ethics of what to do with Bayu

and toward new questions of how to leverage Bayu’s case toward

the routinization of medical referral protocols and the development

of cutting edge post-conflict reintegration projects that take PTSD

seriously. Dr. A’s own voice from Bireuen is absent from the discussion even though he and his colleagues in Bireuen all had email

addresses of their own and, as I show below, knew more about

Bayu’s case than anyone else at IOM. By paying attention to the

presence or absence of voices and the direction of interactions in

the email archive, we discern the contours of a differential network

of actors and learn who is authorized to speak, or even who is

authorized to change another’s medical diagnosis.

Dr. E and her medical team reached consensus and implemented a plan of action following this thread of emails concerning

Bayu. Her report shows mastery of bureaucratic aesthetics with its

bullet lists and numbered conclusions that mediate social action far

more effectively than long form ethnographic field notes

(Strathern, 2006). She also brings together Dr. C’s, Dr. A’s, and my

assessments of Bayu into a single document that she went on to use

as an exemplary case study that the medical teams in all ten offices

studied and assimilated into their treatment and referral protocols,

with Dr. C on retainer by telephone and email for cases that

required his psychiatric expertise.

Dr. E’s final medical report assumes the sociological status of

what Latour calls a “black box,” which designates any combination

of ideas, objects, and people whose output is assumed to be truth.

The inner workings of the black box become invisible through its

own success because “one need only focus on its inputs and outputs

and not on its internal complexity” (Latour, 1999, p.304). When Dr.

E uses her report to train her staff, there is no need to revisit the

messy details surrounding Bayu’s case that brought disparate

stakeholders together to deliver this document. In turn Dr. E’s

eventual report to IOM’s donor would become a higher order black

box within which the treatment protocol based on Bayu’s case is

just one of the objects inside it that enabled the apparent success of

IOM’s post-conflict medical humanitarian program.

Returning to the email archive allows us to not only reopen

IOM’s black box products and trace out the threaded conversations

and negotiations among a network of actors that came together to

produce success; the archive also allows us to revisit and ask how

dozens of other problems that IOM faced failed to produce black

box reference points throughout the duration of the post-conflict

program. Dr. E successfully developed a referral and treatment

protocol for mental health cases, an important early step in the life

of IOM’s post-conflict medical program and a credit to Dr. E’s

administrative skill, but D and the Chief of Mission never developed

an international best practices model for incorporating PTSD

treatment into post-conflict reintegration programs. Moreover,

even though both Dr. E and D strongly agreed that IOM should do

everything to get their client out of jail, he nevertheless served a 14month sentence for stealing his village head’s motorbike. For this

Within 12 h of Dr. E’s first email, our last minute security

clearances to travel were approved and we started our five-hour

trip to Bireuen. Upon arrival late in the afternoon, Dr. C and I first

picked up Dr. A at IOM’s newly opened office, and then went to the

police station to meet and examine Bayu. We were originally under

the impression Bayu had an uncontrollable psychosis and putting

him in jail was his sister’s ad-hoc solution, but when the officers

brought him out of a bedroom-sized cage full with other men to

meet with us, we were surprised that he was capable of participating in a fairly coherent conversation, albeit in a slow motion,

weak and resigned, manner.

We sat on a bench in a quiet area of the station. Bayu looked

disheveled and his skin was covered with a common fungal infection. His face was empty of emotions and he avoided eye contact.

He could not speak Indonesian. Dr. C gave Bayu a cigarette and

conducted his clinical interview in Acehnese. In what struck me as a

self-defeating capitulation to the prevailing narrative regimedin

which more powerful actors in Bireuen charged with saying what

counts as true (Foucault, 1980) determine “what Bayu did” for

everyone elsedBayu freely admitted that he stole the village head’s

motorbike, perhaps due to lack of insight into his own condition. As

Dr. C reported later, Bayu acknowledged regret. Dr. C did not spend

more than ten minutes with Bayu, then he spoke with some police

officers who confirmed that the village head had Bayu arrested for

stealing his motorbike. They told us the easiest way to get Bayu out

of jail would be if the village head retracted his charges.

Eager to return to Banda Aceh, Dr. C quickly concluded that Bayu

merely had a mild depression and knowingly committed a crime, so

it would be hard to get him out of jail on ethical or medical grounds.

But something felt amiss. The Bayu we met at the police station did

not match the description that brought us so urgently to Bireuen on

his behalf. During a break for the magrib evening prayers, I

conferred with Dr. A and the head of IOM’s Bireuen office, M. They

suggested we go to Bayu’s village to meet with his sister and the

village head. Dr. C relented when we presented him with the new

plan. Following security procedures for traveling outside city limits

after dark, we took two IOM-marked vehicles to Bayu’s village

twenty minutes away. Fancy cars rarely travel off the main roads in

Aceh, much less two of them at night; upon arrival the rare sight of

our little convoy off the main road attracted a crowd, especially as it

brought a tall foreigner and a psychiatrist in city clothes. As a large

group gathered, I worried that any information we heard from

Bayu’s sister might be biased toward an inoffensive public narrative. This was when Dr. A and M proved indispensable. M has a

background in journalism, and he reported extensively on conflict

events before the peace agreement; his reporter’s instincts kicked

in and he quietly withdrew from the crowd and did some private

crosscheck with other neighbors.

The story that emerged was significantly different from what the

police or Bayu himself had told us earlier. No one in the village

believed that Bayu was ever a member of GAM during the conflict.

Rather, they described Bayu in those days as a kind of quiet village

simpleton who harvested coconuts for a living, a task usually

handled by young adolescents, but they emphasized that he was

otherwise fine before his incarceration. As a political prisoner, he

was beaten severely on the head at least once that resulted in major

swelling of his head, which suggested to me some kind of organic

�J.H. Grayman / Social Science & Medicine 120 (2014) 334e343

head trauma. Bayu exhibited odd behavior that did in fact disrupt

the community only after his release from jail. When he received

his first reinsertion cash grant immediately upon amnesty, Bayu’s

sister was unsettled to discover that he “gave all the money away”

before he even got home. In the village, he started to take things

and put them somewhere else; small things like coconuts and

chickens, and big things like cows and motorbikes. He never kept

the objects or tried to sell them, nor did he try to hide what he was

doing, and he was frequently caught. At night, Bayu would take off

his shirt, sling it over his shoulder, put on a backpack and go

walking through the village, back and forth behind people’s houses.

His behavior disturbed the community but they also understood his

condition as stres sustained during his incarceration. Stres, a

misleading colloquial Indonesian gloss of the English word stress,

typically suggests a serious, long-term, and debilitating condition

that may require psychiatric care at a hospital (Grayman et al.,

2009, p.299). When Dr. C asked if Bayu had ever shown signs of

violence, his sister told us that Bayu had threatened her with a

stone and once hit her daughter.

Then one day Bayu took the village head’s motorbike, put it

behind an empty house, and just left it there. The village head’s

brother is a military officer; he found Bayu, beat him, and delivered

him to the police station for arrest. When we asked to meet the

village head to hear what he had to say, the neighbors warned us

that a conversation with him would quickly complicate matters,

involving not just the police but also the military, and inevitably

ending with a ransom demand for removing the charges he pressed

against Bayu. Apart from their dismay about the village head’s

drastic action against Bayu, there was apparently some collective

malcontent with his leadership and the neighbors did not want to

draw him into the conversation, so they called the village secretary

instead.

Our visit to the village raised enough questions to persuade Dr. C

to change his diagnosis to PTSD, which we hoped might justify

dropping the charges and allow IOM to arrange treatment. Nevertheless I was struck by how Dr. C was at first so convinced by the

self-evident truth of the police charges against Bayu that he never

considered anything other than pure criminal intent once he

discovered that Bayu could articulate answers to his questions and

express remorse. As we drove back to Bireuen from the village, Dr. C

told us the story of how he got his start in psychiatry as a doctor in

the Indonesian military. As an Acehnese Indonesian, Dr. C left the

army as soon as possible to avoid the pressure of divided loyalties

during the GAM insurgency. Dr. C’s admission helped me understand how in the face of Indonesian security forces, police included,

he too found it easier to capitulate to the prevailing narrative

regime rather than involve himself in a humanitarian effort to get

Bayu out of jail.

Our trip to Bireuen introduced us to a complicated narrative

about the parochial spoils of peace that converged upon Bayu and

created a stalemate that left him in jail to serve a complete 14month sentence. Bayu’s sister asked us repeatedly about his next

cash installment instead of his psychiatric condition. She argued

that she should assume responsibility for his cash before someone

else did. Just outside her house, a process of rapid political transformation had consumed her village (and all of Aceh) as GAM’s

amnestied prisoners and ex-combatants publicly returned to their

communities and asserted their newly established rights to

participate in local governance. A village head with family connections to the military may have protected the community during

the conflict, but under the new peacetime conditions it had turned

into a liability. This village wanted to replace their leader, not least

for sending his soldier-brother to beat and arrest a vulnerable

member of their community whose strange behavior required a

particular sort of blind spot similar to Dr. C’s to label it criminal.

341

Based on what the neighbors and the police told us about what

it would take to get Bayu out of jail, it was clear to us that the village

head and his military brother, perhaps together with the local police, were engaging in the same predator economy that prevailed

during the conflict, knowing they might siphon off Bayu’s peace

dividend in return for dropping the charges. Local elites finding

ways to capture the spoils of peace is a well-documented phenomenon among practitioners of post-conflict disarmament,

demobilization and reintegration programs (Knight and Özerdem,

2004; Willibald, 2006), hence D’s insistence that reinsertion

assistance should only be handed over to individual beneficiaries.

In this case, however, IOM’s insistence contributed to a frosty

standoff in which Bayu simply remained in jail without psychiatric

care.

5. Discussion: patients lost in the inbox

Dr. E’s new treatment and referral protocol that used Bayu as a

case example relied heavily upon email as the reporting instrument. IOM’s doctors across Aceh routinely sent patient reports to

Dr. B in Banda Aceh who sorted and compiled them for Dr. E’s reports to IOM donors. For psychiatric cases, Dr. C made routine road

trips and prepared reports for each of the dozens of patients he met

in the field. A focus on referral, documentation, compilation, and

circulation over email enhanced the routinization and bureaucratization of medical practice at the expense of humanitarian advocacy for individual patients whose details were lost in the many

reports attached to emails that accumulated downward in the

inbox.

It was only while preparing an earlier draft of this article in 2013

that I discovered Bayu’s fate, buried and overlooked in an 80-page

email attachment that lists Dr. C’s patient exam reports. Despite her

lack of psychiatric training, the IOM nurse in Bireuen conducted

Bayu’s first follow-up exam at the jail. She reported that Bayu was

mentally stable, noting only his hygiene as a sign of poor self-care.

When she asked him what he did with his first reinsertion payment, he told her that he used most of it to pay off debts, and the

rest to buy coffee and cigarettes for all his friends in the village. This

accords with how most of the amnestied prisoners in Aceh reported

using their reinsertion assistance, and serves as a defense against

Bayu’s sister’s less sympathetic assertion that he “gave all the

money away.” Dr. C conducted Bayu’s third exam in late February

2006, long after specific attention to Bayu’s case had disappeared.

His report begins with the news of the judge’s 14-month sentence.

Then he lists Bayu’s symptoms: blunted affect, poor hygiene, loose

association, disturbed judgment, and auditory hallucinations. Dr. C

diagnoses Bayu with an unspecified psychotic disorder, prescribes

medication, and refers Bayu to the psychiatric hospital, “if it is

possible.”

In their review of the Inter-Agency Standing Committee’s

Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency

Settings (IASC, 2007), Sharon Abramowitz and Arthur Kleinman

(2008) have argued that international humanitarian interventions

operate simultaneously at two levels to produce unique structural

and cultural contexts of suffering and care. There are global operations where international agencies fund and organize the provision of services, and local operations where practitioners engage

directly with beneficiaries in settings of instability. The two contrasting representations of Bayu’s case using IOM’s email archive

and my participant-observations correspond to these levels of humanitarian practice and illustrate how their prevailing narrative

regimes rarely overlap.

IOM staff in the field with the most knowledge about their

beneficiaries turn out to be the voices least authorized to speak

through a communication technology that closely reproduces

�342

J.H. Grayman / Social Science & Medicine 120 (2014) 334e343

organizational hierarchy and favors the voices of elite decisionsmakers. These managerial conversations emphasize project policies, proposals, and reports over actual program dynamics on the

ground. The routinization and bureaucratization of care through

email relies upon the creation of black box products that ensure the

smooth operation of IOM’s post-conflict medical program but result

in less accountability to individual patients. Discussions by email

that shift away from actors on the ground toward managers in

Jakarta and feature the compilation and packaging of summary

reports reflect IOM’s competing accountability to another set of

beneficiaries: its donors.

Email communication technology productively generates and

reproduces the image of the mobile sovereign as IOM managers

conduct business across global distances by rapid, always available

telecommunication technologies, enacting durable tropes of humanitarian immediacy. The email archive preserves the traces of a

rapid investigation and programmatic response less than a week

after the identification of a problem. The urgent velocity of these

rapid communications briefly linked a powerful network of stakeholders in Jakarta, Geneva, and Cambridge to a particular case in

Aceh, which in turn consolidated the support needed within IOM to

ensure that mental health would be a part of the post-conflict

reintegration agenda for the next four years. But this global-level

operational success came at the expense of local operational support. Upon completion of her new patient protocol in Jakarta, Dr. E

confidently instructed her staff by email to prepare an allexpenses-paid referral for Bayu’s psychiatric care in Banda Aceh

without accounting for the enduring conditions of chronic instability in Bireuen, including her own staff’s tactical (and understandable) refusal to challenge official narratives purveyed by the

police and military about “what Bayu did.” These mediated exchanges in the email archive record and project IOM’s seamless

management of their humanitarian bureaucracy, but also produce

fields of invisibility that mask a range of local complexities on the

ground.

A discussion of these complexities might begin with Bayu’s

changing diagnosis. Recent studies of violence and mental health in

post-conflict settings have aimed to clarify the links between

traumatic experiences of the past and daily stressors in the present

(Miller and Rasmussen, 2010; Panter-Brick, 2010), but Bayu’s case

illustrates another challenging dimension to consider: psychiatric

sequelae born out of organic head injuries sustained during conflict, or in Bayu’s case, while in prison. In this respect Bayu’s case is

hardly unique; reports of changed behavior in the wake of injuries

to the head were a persistent leitmotif of our fieldwork. In a

random, population-based sample of high-conflict communities in

Bireuen, 29% of men and women over age 17 (N ¼ 180) reported

beatings to their head during the conflict, and 68% of men in Bayu’s

age cohort (17e29, N ¼ 23) reported any type of head trauma,

including beatings, suffocation, strangulation, and drowning (Good

et al., 2006, p.16, p.35). Head trauma may have long-term effects on

behavior and other cognitive functions, which can be mistaken for

criminal behavior (Sarapata et al., 1998; León-Carrión and Ramos,

2003). Bayu’s casedand Aceh’s post-conflict landscape more generallydillustrates the relevance of psychiatric symptoms associated with head injury for humanitarian actors and health

professionals working in post-conflict settings, but IOM’s incipient

program and Aceh’s available psychiatric resources in 2005 did not

yet have the capacity to assess much less effectively treat cases like

Bayu’s.

Instead IOM relied upon the more familiar discourse of trauma,

a shorthand diagnosis that designates Bayu as a victim worthy of

humanitarian compassion. By reframing Bayu’s behavior within

what Erica James calls the “compassion economy,” part of a larger

“political economy of trauma” (2010, p.107), we hoped Bayu’s PTSD

diagnosis might facilitate his release from jail. But IOM’s humanitarian argument did not gain persuasive traction against Bireuen’s

entrenched “terror economy” (2010) that held Bayu for ransom as a

criminal and arguably prevented Dr. C from pursuing Dr. E’s

directive to get Bayu out of jail and into treatment. Bireuen’s postconflict complexities caution against easy conclusions that assert

“local knowledge” as an alternative to the unattended prescriptions

purveyed by humanitarian experts. Dynamics in Bireuen utterly

resisted our (admittedly insufficient) efforts at compassionate

intervention, highlighting the limits of intervention and its sustainability, particularly in settings where strong state institutions

assert their control.

IOM’s protocol for mental health cases in post-conflict Aceh was

an ad-hoc exercise in telemedicine in which field doctors consulted

by phone and email with Dr. C in Banda Aceh. Dr. E designed it this

way not just because tsunami-damaged roads and security concerns complicated travel, but also because Aceh faces a critical

shortage of specialists. In 2008 there were only 3.45 specialist

doctors for every 100,000 people in Aceh (Meliala et al., 2013), and

at the time of Bayu’s arrest in late 2005, there were only 4 psychiatrists in Aceh for a population of 4 million people. Dr. C worked

only part-time for IOM because he also had to teach at the local

university, conduct rounds at the provincial psychiatric hospital,

and run his private practice. Remote consultation offered a temporary solution in a setting of widely unmet psychiatric needs

following Aceh’s twin disasters of conflict (Good et al., 2006, 2007;

Grayman et al., 2009) and tsunami (Irmansyah et al., 2010; Musa

et al., 2014). But I would also argue that the deterritorialized

immediacy afforded by IOM’s ever-reliable email network

contributed to the organization’s distorted perception of what it

could achieve across a vast and unstable landscape. As lessons from

the field eventually revealed the shortcomings of their approach,

IOM reoriented its clinical psychiatric model of care to mobile

outreach with an emphasis on psychiatric training for general

practitioners and community mental health nurses.

6. Conclusion

The first goal in this article is to illustrate the productive

analytical possibilities of conducting an ethnography of medical

humanitarianism through a content analysis of the email archive.

As a dominant communication technology, it is easy to take the

everyday use of email for granted as a neutral and transparent

purveyor of content. Email’s speed and efficiency brings powerful

and decisive immediacy to office communications but this technological advantage masks mediation effects in crisis settings such

as the amplification of the humanitarian imperative, the emphasis

on acute over chronic crises, and the reproduction of organizational

hierarchies. The second goal of this article is to draw attention to

email’s mediation effects in medical humanitarian settings. Email

produces a false sense of proximity to the field, as if doctors in

Jakarta and Banda Aceh were intimately involved in the delivery of

post-conflict medical services in Bireuen. Instead we see that email

further abstracts distant doctors away from local contexts of

suffering and care. The recommendation is not to abandon such a

useful management tool but rather to actively train and empower

staff on the front lines of program implementation, ensuring their

voices and data provide meaningful contributions that will not slip

down the inbox.

Acknowledgments

I thank the Fulbright and Wenner-Gren Foundations, as well as

the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI, Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia) and the Center for the Development of Regional

�J.H. Grayman / Social Science & Medicine 120 (2014) 334e343

Studies at Syiah Kuala University (PPSK-UNSYIAH, Pusat Pengembangan Studi Kawasan) for their support and sponsorship of my

field research in Aceh, Indonesia. Participants of a seminar held in

the Division of Sociology at Nanyang Technological University,

especially Kwok Kian Woon, Michael M.J. Fischer, Susann Wilkinson, Sulfikar Amir, and Patrick Williams provided valuable suggestions on an earlier presentation of this paper; so did the

participants of a workshop on the anthropology of intervention

sponsored by Wenner-Gren and McMaster University (Hamilton,

ON). I also thank Bobby Anderson, Greg Beckett, Mary-Jo DelVecchio Good, Michelle Bunnell Miller, and Pierre Minn, as well as

three anonymous reviewers and the editors at Social Science &

Medicine for their close readings and critical feedback. Finally, I

thank the Indonesian and international staff at IOM’s post-conflict

reintegration program in Aceh for welcoming an anthropologist

among their ranks.

References

Abramowitz, S., Kleinman, A., 2008. Humanitarian intervention and cultural

translation: a review of the IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial

support in emergency settings. Intervention 6 (3/4), 219e227.

Anderson, B.R., 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread

of Nationalism. Verso, London & New York.

Agamben, G., 2005. State of Exception. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Altheide, D.L., 1987. Reflections: ethnographic content analysis. Qualitative Sociology 10 (1), 65e77.

Appadurai, A., 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization.

University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN.

Aspinall, E., 2009. Islam and Nation: Separatist Rebellion in Aceh, Indonesia. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA.

Boellstorff, T., 2010. Coming of Age in Second Life: an Anthropologist Explores the

Virtually Human. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Calhoun, C., 2008. The imperative to reduce suffering: charity, progress and

emergencies in the field of humanitarian action. In: Barnett, M., Weiss, T. (Eds.),

Humanitarianism in Question: Politics, Power, Ethics. Cornell University Press,

Ithaca, NY, pp. 73e97.

Engelke, M., 2010. Religion and the media turn: a review essay. American Ethnologist 37 (2), 371e379.

Fassin, D., 2007. Humanitarianism as a politics of life. Public Culture 19 (3), 499e

520.

Fassin, D., 2012. Humanitarian Reason: a Moral History of the Present. University of

California Press, Berkeley.

Fassin, D., Vasquez, P., 2005. Humanitarian exception as the rule: the political theology of the 1999 tragedia in Venezuela. American Ethnologist 32 (3), 389e405.

Foucault, M., 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings

1972e1977. Pantheon Books, New York.

Gershon, I., 2010. Breaking up is hard to do: media switching and media ideologies.

Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 20 (2), 389e405.

Good, B., Good, M.D., Grayman, J., Lakoma, M., 2006. Psychosocial Needs Assessment of Communities Affected by the Conflict in the Districts of Pidie, Bireuen,

and Aceh Utara. International Organization for Migration, Jakarta.

Good, M.D., Good, B., Grayman, J., 2010. Complex engagements: responding to

violence in postconflict Aceh. In: Fassin, D., Pandolfi, M. (Eds.), Contemporary

States of Emergency: the Politics of Military and Humanitarian Interventions.

Zone Books, New York, pp. 241e266.

Good, M.D., Good, B., Grayman, J., Lakoma, M., 2007. A Psychosocial Needs

Assessment of Communities in 14 Conflict-affected Districts in Aceh. International Organization for Migration, Jakarta.

343

Grayman, J.H., Good, M.D., Good, B., 2009. Conflict nightmares and trauma in Aceh.

Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 33 (2), 290e312.

Hull, M.S., 2012. Documents and bureaucracy. Annual Review of Anthropology 41,

251e267.

IASC, 2007. Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency

Settings. Inter-Agency Standing Committee, Geneva.

Irmansyah, I., Dharmono, S., Maramis, A., Minas, H., 2010. Determinants of psychological morbidity in survivors of the earthquake and tsunami in Aceh and

Nias. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 4, 1e10.

James, E.C., 2010. Ruptures, rights, and repair: the political economy of trauma in

Haiti. Social Science & Medicine 70 (1), 106e113.

Knight, M., Özerdem, A., 2004. Guns, camps and cash: disarmament, demobilization

and reinsertion of former combatants in transitions from war to peace. Journal

of Peace Research 41 (4), 499e516.

Latour, B., 1996. Aramis, or, the Love of Technology. Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, MA.

Latour, B., 1999. Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. Harvard

University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Latour, B., 2005. Reassembling the Social: an Introduction to Actor-network Theory.

Oxford University Press, Oxford.

León-Carrión, J., Ramos, F.F.J.C., 2003. Blows to the head during development can

predispose to violent criminal behaviour: rehabilitation of consequences of

head injury is a measure for crime prevention. Brain Injury 17 (3), 207e216.

Mazzarella, W., 2006. Internet x-ray: E-Governance, transparency, and the politics

of immediation in India. Public Culture 18 (3), 473e505.

Meliala, A., Hort, K., Trisnantoro, L., 2013. Addressing the unequal geographic distribution of specialist doctors in Indonesia: the role of the private sector and

effectiveness of current regulations. Social Science & Medicine 82, 30e34.

Miller, K.E., Rasmussen, A., 2010. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health

in conflict and post-conflict settings: bridging the divide between traumafocused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science & Medicine 70 (1), 7e16.

Musa, R., et al., 2014. Post tsunami psychological impact among survivors in Aceh

and West Sumatra, Indonesia. Comprehensive Psychiatry 55 (Suppl. 1), S13e

S16.

OCHA, 2013. Humanitarianism in the Network Age. United Nations.

Pandolfi, M., 2003. Contract of mutual (in)difference: governance and the humanitarian apparatus in contemporary Albania and kosovo. Indiana Journal of

Global Legal Studies 10 (1), 369e381.

Pandolfi, M., 2008. Laboratory of intervention: the humanitarian governance of the

postcommunist Balkan territories. In: Good, M.D., Hyde, S.T., Pinto, S., Good, B.J.

(Eds.), Postcolonial Disorders. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp. 157e

187.

Panter-Brick, C., 2010. Conflict, violence, and health: setting a new interdisciplinary

agenda. Social Science & Medicine 70 (1), 1e6.

Redfield, P., 2005. Doctors, borders, and life in crisis. Cultural Anthropology 20 (3),

328e361.

Redfield, P., 2012. The unbearable lightness of ex-pats: double binds of humanitarian mobility. Cultural Anthropology 27 (2), 358e382.

Reid, A., 2006. Verandah of Violence: the Background to the Aceh Problem. NUS

Press, Singapore.

Sarapata, M., Herrmann, D., Johnson, T., Aycock, R., 1998. The role of head injury in

cognitive functioning, emotional adjustment and criminal behaviour. Brain

Injury 12 (10), 821e842.

Skovholt, K., 2009. Email Literacy in the Workplace: a Study of Interaction Norms,

Leadership Communication, and Social Networks in a Norwegian Distributed

Work Group (PhD dissertation).

Strathern, M., 2006. Bullet-proofing: a tale from the United Kingdom. In: Riles, A.

(Ed.), Documents: Artifacts of Modern Knowledge. University of Michigan Press,

Ann Arbor, MI, pp. 181e205.

Vigh, H., 2008. Crisis and chronicity: anthropological perspectives on continuous

conflict and decline. Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 73 (1), 5e24.

Willibald, S., 2006. Does money work? Cash transfers to ex-combatants in disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration processes. Disasters 30 (3), 316e339.

�