® Academy of Management Journal

2003, Vol. 46, No. 1, 13-26.

META-ANALYSES OF FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE

AND EQUITY: FUSION OR CONFUSION?

DAN R. DALTON

CATHERINE M. DAILY

Indiana University

S. TREVIS CERTO

Texas A&M University

RUNGPEN ROENGPITYA

Indiana University

Agency theory dominates research on equity holdings-firm performance relationships;

however, extant studies provide no consensus about the direction and magnitude of

such relationships. Consistent linkages have not been demonstrated for firm performance and CEO, officer, director, institutional, or blockholder equity. We conducted a

series of meta-analyses of relevant empirical ownership-performance studies. The

meta-analyses provide few examples of systematic relationships, lending little support

for agency theory. We propose a substitution theory perspective for future ownershipperformance research.

bility that the owners and managers of a firm might

have divergent, or misaligned, interests. In fact, a

central principle of agency theory is that high-ranking

corporate officers, acting as the agents of shareholders, can pursue covnses of action inconsistent with

the interests of owners (e.g., Eisenhardt, 1989; Jensen

& Meckling, 1976; Shleifer & Vishny, 1997).

This potential confiict of interests has become a

central focus of corporate governance. Macey explained that "corporate governance can be described

as the processes by which investors attempt to minimize the transactions costs (Coase, 1937) and agency

costs (Jensen & Meckling, 1976) associated with doing

business within a firm" (1997: 602). The ability of

equity holdings to address the agency problem and

enhance firm financial performance was the focus of

our study. Extant literature refiects two common

themes with regard to mitigating agency costs. The

first, which we will refer to as "aligrmient," was

nicely captured by Himmelberg, Hubbard, and Palia,

who wrote that "it is well known" (1999: 354) that a

potential solution to the fundamental agency problem is to provide managers with equity stakes in their

firms. Thus, managerial self-interest may be mitigated

by aligning the interests of managers and shareholders, and it is presumed firm performance will improve as managers concurrently work for their own

and shareholders' benefit (e.g., Jensen & Murphy,

1990; Perry & Zenner, 2000).

The second view, illustrated by Agrawal and Knoeber's (1996) work, we will refer to as the "control"

approach (also see Bethel, Liebeskind, and Opler

Adam Smith, in An Inquiry into the Nature and

Causes ofthe Wealth of Nations, provided one of

the earliest discussions of the problem of the separation of ownership and control. He suggested that

managers of other people's money cannot be expected to "watch over it with the same anxious

vigilance" one would expect from owners and that

"negligence and profusion, therefore, must always

prevail, more or less, in the management of the

affairs of such a company" (Smith, 1776/1952:

324). This sentiment presages the essence of agency

theory, a theory that has been characterized as "a

theory of the ownership (or capital) structure of the

firm" (Jensen & Meckling, 1976: 309).

Agency theory has been the dominant theme of

empirical examinations of the relationship between

equity ownership and financial performance (e.g.,

Thomsen & Pedersen, 2000). Agency theory is largely

groimded in the seminal work of Berle and Means

(1932), who suggested that a fundamental shift occurred in the early 1900s. At that time, professional

managers with little or no equity increasingly gained

day-to-day management responsibility for firms

that had previously been actively managed by their

owners. With this separation of roles arose the possi-

The authors wish to thank Professor Frank L. Schmidt

for his generous counsel regarding certain technical aspects of our meta-analysis. His was a substantial contribution to this work, and his willingness to share his time

and expertise was a model of collegiality.

13

�14

Academy of Management Journal

[1998] and Dalton, Daily, Ellstrand, and Johnson

[1998]). Here, concentrated shareholdings may facilitate the monitoring of firms' managements and lead

to improved finn perfonnance. The ownership shares

of two types of outside owners, institutions and

"blockholders," are typically sufficiently large that

these equity owners "are positioned to see to it that

management serves their interests" (Demsetz & Lehn,

1985: 1161) and this "ought to yield higher profit

rates" (Demsetz & Lehn, 1985: 1174).

Although agency theory predicts that equity holdings have important implications for firm performance, the empirical evidence provides no consensus on the relationship between equity holdings by

various constituent groups and financial performance. Bothvi^ell (1980: 304), for example, noted that

the results of studies examining the relationship of

equity with firm performance have been "quite

mixed." Hunt concluded that "it is difficult to draw

any firm conclusions . .. since no consensus has developed" (1986: 96). More recently. Short noted that

"the results of these studies are inconclusive" (1994:

206). Also, Rediker and Seth observed that "there is a

singular lack of consistency in the empirical results

reported" (1995: 86]. The lack of consistency notwithstanding, McConnell and Servaes observed that "a

consensus interpretation is that the allocation of

equity ownership matters" (1995:133). In light ofthe

inconsistency in the empirical findings, it was this

latter observation that guided our research.

Given the continuing interest in and empirical attention to equity holdings and their relationship to

financial performance, and the dominance of agency

theory as a theoretical foundation for these studies,

we conducted a series of meta-analyses to examine if

some synthesis in these relationships could be demonstrated. Our analysis is based on the equity ownership categories found in extant empirical research

(e.g., McConnell & Servaes, 1990, 1995). The discussion of equity categories and their relationship to firm

performance as a fiinction of the alignment or control

perspective is followed by an overview of our metaanalytical procedures, the results of our analyses, and

a discussion of theoretical and practical implications

of our study findings.

HYPOTHESES

Inside Equity Holdings

Agency theory provides the rationale for improved

firm performance when managers' interests are

aligned with those of shareholders through managerial equity holdings. Jensen and Meckling specifically

identified "the fraction ofthe equity held by the manager" (1976: 343) as fundamental to ownership struc-

February

ture. This same rationale has been applied to board

members as well. Officers and directors, in various

combinations, constitute inside equity holders (e.g..

Bethel & Liebeskind, 1993). Careful review of extant

empirical research shows the following inside equity

categories: CEO equity holdings, managerial equity

holdings, officer and director equity holdings, inside

board equity holdings, and outside board equity holdings. These categories guide the following discussion.

Agency theory suggests that when insiders hold

substantial equity positions in the firms they serve,

they are more likely to act in shareholders' interests, given their shared financial interests (Bryan,

Hwang, and Lilien [2000] and Perry and Zenner

[2000], among others, provide overviews). This is

the alignment rationale to which we previously

referred. Following this rationale, Jensen and Murphy (1990) noted that stock ownership causes executives' wealth to vary directly with company performance. Absent an equity investment in a firm,

executives are more likely to behave opportunistically by supporting projects that further their own

interests, at shareholders' expense, and to behave

in a manner that further ensures their individual

job security (Himmelberg et aL, 1999; Zahra,

Neubaum, & Huse, 2000). Eisenhardt (1989) identified this propensity for self-interest as a fundamental element of agency theory.

Researchers have also applied this alignment rationale to corporate board members. Many empirical

studies, for example, rely on "officer and director

equity" to capture insider equity ownership (Jensen,

1993]. Some board members also serve as officers in

their firms (inside directors], and the remainder are

norunanagement board members (outside directors].

Regardless of the relationship a director has with a

firm, the board, as a decision-making body, operates

within the boundaries of the corporation. On this

basis, then, board members are subject to the same

alignment incentives as corporate officers. Jensen

(1993], for example, did not distinguish between officers and directors in his observation that agency

problems are likely to occur when officers and directors do not directly share in the appreciation of their

firms' equity. Substantial equity stakes, however, provide these individuals with enhanced incentives to

effectively manage firm performance for the benefit of

shareholders.

Regardless of whether inside equity holders are

CEOs, officers, or directors, the alignment perspective suggested by agency theory principles supports

a positive relationship between insider equity

holdings and firm performance. The central idea is

that equity stakes will resolve conflicts of interest

between corporate insiders and shareholders, with

a resultant impact on shareholder value.

�2003

Dalton, Daily, Certo, and Roengpitya

Hypothesis 1. Insider equity holdings will

be positively associated with firm financial

peiformance.

Outside Equity Holdings

Agency theory is also informative with regard to

the anticipated relationship between outside equity

holdings and firm performance. Extant research has

identified two central categories of external equity

owners: institutional investors and blockholders.

Here, the agency theory rationale for a relationship

between these equity holders and firm performance

is one of control. Institutional investors' and blockholders' equity holdings are sufficiently large to

encourage these equity holders to actively monitor

firms' decision makers to ensure that the firms are

being operated in the best interests of shareholders.

Institutional investor equity holdings. Institutional investors have become a powerful force in

the corporate landscape, controlling approximately

half of the United States equity market (Conference

Board, 2000) and accounting for approximately 80

percent of all daily transactions on the U.S. stock

exchanges (Zahra et al., 2000). Given their substantial collective equity positions, the institutional investment community has an obvious incentive to

vigilantly monitor the officers and directors in

whose firms they invest in order to promote these

firms' long-term performance (e.g., Alchian & Demsetz, 1972; Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). This oversight

is consistent with agency theory and a means of

constraining opportunism (e.g., Useem, 1996). We

should note that institutional fund managers are

themselves agents; nonetheless, fund managers

have demonstrated a decided propensity to actively

monitor executives in the firms in which their

funds invest (e.g.. Black, 1992). Institutional fund

managers have been particularly effective in

achieving governance changes in the firms they

target (e.g., Wahal, 1996).

Institutional monitoring is aimed at improving

firm performance. As one fund manager noted,

"Whatever we do in the area of proxy initiatives or

voting proxies, there has to be fundamentally an

economic motivation behind it. Before we devote

resources to something we really have to be able to

say that this is going to leave our participants better

off than if we hadn't done it" (Useem, Bowman,

Myatt, & Irvine, 1993: 181).

Hypothesis 2. Institutional investor equity

holdings will be positively associated with firm

financial performance.

There are those who remain unconvinced about

the efficacy of institutional investor monitoring in

15

relation to financial performance. Some inconsistency in findings with regard to institutional investor equity holdings and financial performance may

be attributable to the heterogeneity of institutional

investors (e.g., Brickley, Lease, & Smith, 1988). It

has been demonstrated, for example, that different

classes of institutional investors have different objectives (e.g., David, Kochhar, & Levitas, 1998;

Kochhar & David, 1996). According to Brickley and

his colleagues (1988), the propensity to engage in

monitoring differs for "pressure-resistant," "pressure-sensitive," and "pressure-indeterminate" institutional investors; we define and discuss each

type below.

Pressure-resistant institutional investors include

public pension funds, mutual funds, foimdations,

and endowments. These investors do not normally

have direct business relationships with firms in

which they hold equity. As a result, the managers of

their holdings are not likely to be subject to influence

from the managements of the firms they invest in

(Coffee, 1991). They are the most likely among institutional investors to actively monitor organizational

decision makers and to consequently be labeled "activist institutional investors" (Brickley et al., 1988).

Pressure-sensitive institutional investors include

insurance companies, banks, and nonbank trusts.

These types of institutional investors typically

have ongoing business relationships with many of

the firms in which they hold equity positions.

These relationships create a dependence that may

leave the institutional investors susceptible to managerial influence (Zahra et al., 2000). As a result,

they are unlikely to engage in activity that is perceived as actively monitoring the decision makers

in the firms in which they invest. Davis and

Thompson noted that these funds "have a virtually

unblemished history of passivity" (1994: 162).

Corporate pension funds typify the pressureindeterminate institutional investor category. Relationships between the funds and the firms in which

they invest may exist, but it is less clear than in the

case of the pressure-sensitive investor how these

relationships will affect propensity to monitor. Corporate pension funds are typically managed by professional investment managers selected by a company's management (Fromson, 1990). As a result of

their ties to a firm, these fund managers are unlikely to actively challenge firm decision makers

(Barnard, 1991). Their ties are weaker, however,

than is typical for pressure-sensitive institutional

investors.

Given these differences among institutional investors, we propose:

�16

Academy of Management Journal

Hypothesis 3a. Pressure-resistant institutional

investor equity holdings will be positively associated with firm financial performance.

Hypothesis 3b. Pressure-sensitive institutional

investor equity holdings will be negatively associated with firm financial performance.

Hypothesis 3c. Pressure-indeterminate institutional investor equity holdings will be unassociated with firm financial performance.

Blockholder equity holdings. Blockholders also

have a strong incentive to actively monitor firm management. These equity holders are individuals or

groups holding 5 percent or more of a given firm's

equity. These owners are easily identified, as section

13(d) of the 1934 Securities and Exchange Act requires that "holders of more than five percent of a

class of equity securities held by them are regarded as

a 'group' and are required to file a Schedule 13D

setting forth considerable information concerning the

members of the group" (Sommer, 1990: 368). Any

subsequent sales or purchases of the firm's equity by

these individuals must also be reported.

Agency theory suggests that such large-block

shareholders have both the incentive and influence

to assure that officers and directors operate in the

interests of shareholders [Bethel & Liebeskind,

1993). Demsetz (1983) suggested that the substantial wealth they have at risk implies that the benefits of monitoring will outweigh associated costs.

Blockholders have, in fact, demonstrated their ability to effect changes in the composition of boards

and corporate constitutions (Pound, 1992). Blockholders typically have a stronger incentive than

even activist institutional investors to engage in

control activities. The typical institutional investor

holds, on average, a 1 percent equity stake in a

given firm; by definition, each blockholder in the

same firm holds at least a 5 percent stake.

Hypothesis 4. Large blockholder equity holdings will be positively associated with firm financial performance.

February

sary that a simple correlation between an equity

and a performance variable be available in a publication or derivable from it (methods for converting

other values into correlation coefficients are described by Lipsey and Wilson [2001], Rosenberg,

Adams, and Gurevitch [2000], and Rosenthal and

DiMatteo [2001]).

Using a combination of computer-aided keyword

searches and manual searches of pertinent joumals,

principally in strategic management, finance, economics, and accounting, we obtained a subset of potentially

apphcable research reports. We followed the "ancestry"

approach to article identification (e.g.. Cooper, 1998). By

working carefully from the more contemporary references, tracking the references on which the articles relied, and iteratively continuing this process, it is possible to determine a set of conmion early references with

no published predecessors.

The search process yielded 229 empirical studies

with 1,880 germane bivariate correlations representing a combined sample of 939,567.^ The relatively

large sample-to-study ratio results from the fi-equent

use in governance research of multiple measures of

equity and financial performance. Statistics from

these correlations could only be combined if they

reflected similar study characteristics (e.g., Rosenberg

et al., 2000; Rosenthal & DiMatteo, 2001). The studies

on which we relied do not have that character.

Meta-Analytic Procedures

The meta-analyses were conducted following

guidelines provided by Hunter and Schmidt (1990;

see also Hunter & Schmidt, 1994). Meta-analysis is

a statistical technique for research synthesis that,

while correcting for various statistical artifacts, allows the aggregation of results across separate studies and yields an estimate of the true relationship

between two variables in a population. The zeroorder correlations between the variables of interest

that a study reports are weighted by the sample size

of the study in order to calculate the mean

weighted correlation across all of the studies in the

analysis. The standard deviation of the observed

METHODS

Sample

We employed multiple search techniques to

identify prior empirical research studies that measured equity holdings and firm financial performance. Whether a given indicator of equity or performance was a dependent, independent, or a

control variable in a study was unimportant. These

variables need not have been a main focus to be

included in the meta-analyses. It was only neces-

^ While the total sample size for the combined observations is 939,567, this number is potentially misleading.

Although this sample size is used for a single omnibus

test to establish the potential existence of moderating

influences, it has no utility beyond that as it is artificially

inflated. Consider a study of 100 firms with two distinct

dependent variables and one independent variable. The

study itself would have an n of 100. But it has two

correlations, one for each dependent variable with the

independent variable. The n for the omnibus test, then,

for these two correlations would be 200.

�Dalton, Daily, Certo, and Roengpitya

2003

correlations is then calculated to estimate their

variability. Total variability across studies is comprised of the true population variation, variation

due to sampling error, and variation due to other

artifacts (that is, reliability and range restriction).

Control of these artifacts provides a more accurate

estimate of the true variability.

To control for such artifacts, we relied on Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (Borenstein, 1997), a

software package that employs Hunter and

Schmidt's (1990) artifact distribution formulas. Although other meta-analyses in strategic management (e.g., Boyd, 1991; Capon, Farley, & Hoenig,

1990; Rhoades, Rechner, & Sundaramurthy, 2000;

Schwenk & Shrader, 1993) have treated observed

(not latent) variables as if they were without error

(have a presumed reliability of 1.0), we opted for a

more conservative 0.80 reliability estimate (e.g.,

Dalton, Daily, Ellstrand, & Johnson, 1998, Dahon,

Daily, Johnson, & Ellstrand, 1999).^

RESULTS

The first step in a meta-analysis is to establish a

baseline population correlation (Boyd, 1991; Capon

et al., 1990; Dalton et al., 1998,1999; Rhoades et al.,

2000). More importantly, however, the baseline diagnostics also indicate the potential efficacy of subsequent subgroup analyses. Imagine a hypothetical

meta-analysis with several indicators of performance and several independent variables of interest. If the baseline population correlation were very

near zero and no moderating influences were indicated (that is, the variance was very small), there

would be very little reason to pursue subgroup

analysis. That result (modest correlation and little

variance) suggests no substantive relationships between the variables of interest. For the data we

analyzed, the corrected correlation was a modest

.03, but the variance was much larger than would

^ We do not mean to appear critical about the choice of

reliability level. In the entire data base (229 studies) on

which we relied for this study, equity and financial performance variables were treated as observed in every case,

save one in which a six-indicator performance construct

was used. With that exception, data were not provided on

either the reliability or validity of these measures in any of

these studies. It is apparent that the empirical work in this

area relies on equity and performance variables as observed

and error-free. In the case of the data we used in our metaanalyses, the reliability assumption is robust. As will be

demonstrated in Table 1, the corrected correlation for the

overall test is .03. We also calculated that value with a .6, .7,

and .9 reliability assumption. The largest difference in these

compared to the .8 level was an R^ of .0005.

17

be expected if the population correlation were actually near zero. This pattern suggested that subgroup analyses might be productive.^

Using a test of homogeneity, we assessed

whether the variability in effect sizes was larger

than would be anticipated on the basis of sampling

error. If so, our assumption would be that these

correlations do not estimate a common population

(e.g.. Cooper, 1998; Lipsey & Wilson, 2001).*

Hunter and Schmidt (1990) provided one approach, suggesting that heterogeneity (that is, the

presence of subgroups) is likely if the sampling

error accounts for less than 75 percent of the observed variability. It has also been suggested tbat 90

percent credibility intervals larger than 0.11 imply

the presence of subgroups (Kowlowsky & Sagie,

1993). In the baseline test, both of these indicators

suggested the presence of moderating variables. In

fact, the 90 percent credibility interval was nearly

twice (.208) the standard provided by Kowlowsky

and Sagie (1993).

There are second levels of baseline analysis as well.

The omnibus baseline analysis is the best estimate

of the corrected correlation for all combinations of

^ A potentially important pretest for meta-analysis involves the time frame of studies. Consider a meta-analysis

based on data from 30 to 40 years of empirical work. It is

possible that the earlier work, relying on different measures

and without the benefit of readily available archival data,

would result in different population estimates of r than

more contemporary work. Consider a simple example:

Early work demonstrates a population estimate of a correlation (r) near zero; more contemporary work results in a

much higher estimate ofthe population correlation. If these

two groups of work are combined, the estimated correlation

may be artificially low. We tested for that effect. The research through 1980 on which we relied yielded an estimated correlation of .01; the period from 1981 through

1990, .04; and from 1991 to the present, .02. In each case,

the estimates are very near zero. There is no reason to

believe, then, that the time in which the studies were conducted is of consequence to the analyses.

•• The expressions "subgroup" and "moderator" are used

interchangeably in the meta-analytic literature. This can

lead to some confusion. For a large body of research, a

moderator is ordinarily "operationalized" as a multiplicative variable. In a regression format, one would determine if

the multiplicative term provided marginal variances above

that provided by its elements. The analog for this Ln metaanalysis is accomplished through estahlishing subgroups.

Two separate meta-analyses would be conducted for the

two subgroups. An estimate of the population correlation

would be calculated for each. Then, a critical ratio test

would be used to determine if the two population correlations were statistically different. Throughout the article, we

refer to such testing as "subgroup analysis."

�18

Academy of Management Journal

February

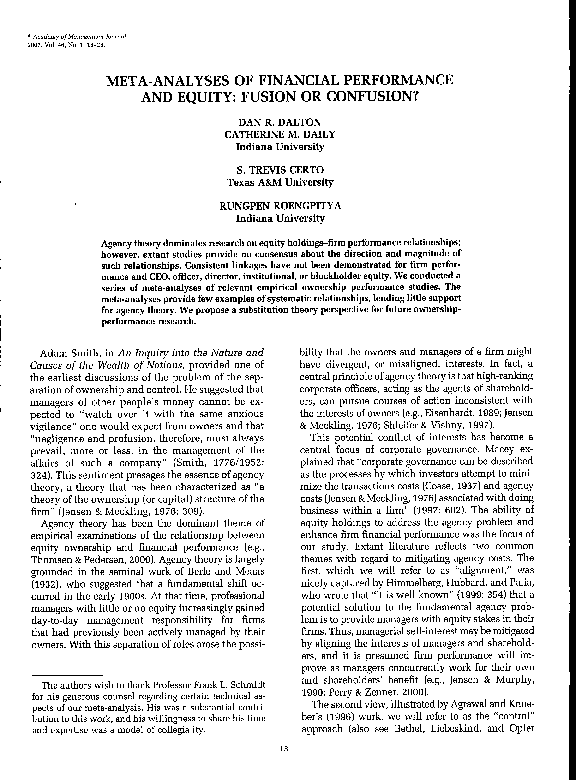

TABLE 1

Meta-Analysis-Corrected Matrix of Population Correlations: Categories of Equity by Financial

Performance Indicators"

Variable

Tobin's Q

ROA

ROA,

IndustryAdjusted''

ROE

ROE,

IndustryAdjusted*"

CEO equity

.05* (14) [6,697]

.09* (10) [3,749] .02 (4) [2,640]

.02 (10) [1,648]

Board equity

.03 (4) [1,402]

.13*" (12) [3,632]

.05*" (16) [4,853] .01 (4) [400]

Officer and

director

equity

.07* (24) [31,381]

.08*'" (7) [6,242]

- . 1 1 * " (5) [1,561] -.02" (6) [612]

Inside board

equity

.00 (4) [991]

Outside board

equity

.06* (4) [2,640]

Management

equity

.01 (10) [9,681]

Institutional

equity

.02*" (89) [119,835] .06* (24) [4,213] .09* (5) [947] -.00 (18) [2,874]

Blockholder

equity

.14* " (14) [14,787] -.02" (33) [27,446]

.11* (9) [3,485]

ROl

ROl,

IndustryAdjusted

- . 1 1 (6) [1,006] -.02* (6) [580]

.01 (5) [1,098]

.09* (8) [3,307] .04 (8) [1,829]

.07 (3) [324]

equity measurements and performance indicators.

An improved approach would be to examine the indicators of financial performance that are current in

the literature (including, Tobin's Q, return on assets

[ROA], return on equity [ROE], return on sales [ROS],

and the price-to-eamings ratio) with equity holdings.

Alternatively, one could examine the individual categories of equity holdings (such as CEO equity, board

equity, institutional equity) with financial indicators.

The results of both these procedures indicated modest levels of corrected correlations. The homogeneity

tests, however, suggested the potential for subgroup

analysis.^

H5rpothesis Tests

Having determined that subgroup analyses were

warranted for individual financial performance

and equity categorizations, we turned to individual

meta-analyses of specific measurements of equity

and performance.*^ To do so, it was necessary to

^ Tables of the second-level base rate analyses would

fill several pages. These data in their entirety are available by request from the first author.

^ The indicators of corporate financial performance

noted in Table 1 reflect those on which the germane

studies rely. There are many other indicators of corporate

performance in the data (for instance, specialized metrics

for banking performance [repossessed assets/total assets.

.00 (11) [3,230]

.07* (8) [1,477]

-.05* "(19) [3,473] .10* (9) [1,003]-.05 (8) [800] .05 (8) [800]

create a matrix of all equity measures by all performance indicators. In a traditional meta-analytical

data presentation, such a matrix would require

many pages. Instead, we constructed a metaanalysis-corrected correlation matrix (Table 1). In

some ways it resembles a correlation matrix. The

cell entries, however, are meta-analysis-corrected

correlation population estimates. Consider the first

entry in Table 1: The best estimate of the actual

population correlation between CEO equity and

Tobin's Q is .051. Tbe number of samples relied on

for this calculation is in parentheses (14 in this

case). In brackets is the sample size (6,697).

Table 1 contains empty cells for two reasons. The first

is a lack of applicable research. For example, we know

of no empirical study addressing the relationship between inside board equity and ROS. Empty cells also

result from there being a low number of relevant studies

from which a meta-analysis can be reasonably interpreted. Clearly, better population estimates can be derived when tiiere are many samples and reasonable

sample sizes (Hunter & Sclunidt, 1990). Although specific guidelines do not exist, three studies would seem

to be a reasonable minimum.

Hypothesis 1 states that insider equity, which was

variously measvired in the studies we analyzed as

Sheshunoff rankings]; slack; value added/employees;

volatility). None of these reach the minimum number of

samples (three) to be included in the table.

�19

Dalton, Daily, Certo, and Roengpitya

2003

TABLE 1

Continued

ROS

Shareholder

Returns

Earnings per

Share (EPS)

Jensen's

Alpha

Ahnormal

Returns

Market-toBook Ratio

.07 (3) [728]

.03 (3) [598]

.03 (13) [4,142]

.09* (9) [2,116]

.03" (15) [4,795]

.17*-" (5) [1,028]

.06*'"(61) [25,361]

.01 (4) [589]

.04* (4) [3,260]

.05 (3) [312]

.23*'(3) [1,729]

-.01 (3) [318]

.07* (5) [1,369]

-.02 (4) [549]

Price-toEarnings Ratio

.04" (6) [1,378]

.06" (9) [1,329]

-.11*-" (7) [717]

.04 (10) [2,700]

.13* " (13) [1,729]

.04* (16) [12,987]

.16*'" (14) [1,436]

.09* " (7) [1,725]

-.00 (3) [3,324]

.04* " (19) [24,492]

.01 (7) [1,835]

.01" (17) [2,641]

.02" (6) [1,749]

.05* (7) [6,733]

-.10* (14) [1,436]

° The number of samples on which a meta-analysis relied is in parentheses; the total sample size for the meta-analysis is in brackets.

A superscript asterisk (*) indicates that the corrected correlation (r) from the meta-analysis is statistically significant. A superscript point

(") indicates that homogeneity tests suggested the presence of moderating variable(s). Empty cells indicate no relevant empirical studies

or less than three observations. Please note that the entries in some cells are not independent from those in others. Consider, for example,

a study that examined the relationship of institutional equity to ROA, ROE, and shareholder returns. That would result in three simple

correlations, which we would use to calculate the results in three cells (i.e., institutional equity with ROA, with ROE, and with shareholder

returns).

"^ In the data on which our meta-analysis relied, only one study used something other than contemporaneous data. In this one study, the

relationship between the amount of outside director equity was examined with ROA (lagged three years). That correlation was .02. That

observation, however, was not included in the analyses appearing in Table 1. There were, however, several cases in which ROA (4

observations) and ROE (12 observations) were measured as multiyear averages that are included in these analyses. We tested the estimated

correlations of these studies with those relying on a single year of ROA and ROE (.011 for a single year; .013 for multiple years).

equity held by CEOs, managers, inside directors,

and/or outside directors, will he positively associated

with financial performance. With a single exception

(officer and director equity as associated with earnings per share [EPS]), in no instance did an estimated

population correlation between measurements of insider equity and financial performance exceed .018 in

variance explained.

Hypothesis 2 proposes a positive relationship between institutional investor equity and financial performance. In this case, too, the relationship with EPS

is tbe largest (r = .129), but none of tbe relationsbips

exceeds .017 in variance explained. Hypotbeses

3a-3c address a finer-grained analysis of institutional

equity, tbe trichotomy of institutional investor types

proposed by Brickley and bis colleagues (1988). We

were able to provide a limited test of the proposition

tbat pressure-sensitive, pressure-resistant, and pressure-indeterminate institutions will demonstrate different relationsbips witb financial performance. Tbe

results are nonsupportive. Corrected correlations

were .05, .10, and .02 for pressure-sensitive, pressureresistant, and pressure-indeterminate institutions, respectively. Tbese differences are not statistically significant. Tbese results, bowever, must be carefully

interpreted as tbere were only seven samples available witb wbicb to test tbis proposition.'' Hypotbesis

4 predicts a positive relationship between blockholder equity and financial performance. Witb tbe

possible exception of EPS, tbere are no substantive

relationsbips (.019 variance explained is the largest).

Tbere is very little evidence for systematic relationsbips between equity and financial performance in

Table 1. Notably, tbe only relationsbips of even marginal consequence involved EPS. Altbougb our rationale for tbose relationsbips is speculative, we note

'' Also, the dependent variables are not the same across

the seven studies.

�20

Academy of Management Journal

tbe following interesting discussion about tbe use of

EPS as an indicator of corporate financial performance. Meyer and Gupta suggested tbat "managers

learned various techniques, including leverage,

aimed at increasing EPS witbout otberwise cbanging

the performance of the firm . . . EPS became a wrong

performance measure as managers adapted tbeir decisions to it" (1994: 323). Perbaps, tben, tbese EPS

relationships are somewhat more subject to manipulation. CoUingwood recently noted tbat "earnings

management pervades tbe U.S. financial system"

(2001: 67).

It may also be notable tbat we saw essentially no

relationsbips among tbe categories of equity bolders

and market returns (sbarebolder returns, Jensen's alpba, and abnormal returns). The bigbest corrected

correlation among tbese is .09. Even so, bowever,

witb tbese and most of tbe accounting performance

measures, there continue to be indications of the

presence of subgroups or moderating infiuences.

DISCUSSION

Tbe universal applicability of agency theory bas

recently been questioned (e.g.. Lane, Cannella, & Lubatkin, 1998). Addressing governance studies specifically, Walsb and Kosnik noted tbat researcbers

"need to be alert to tbe possibility tbat the bypotbesized effects may be mucb more narrowly circumscribed tban tbe theory's proponents might argue"

(1993: 696). Similarly, Davis, Scboorman, and

Donaldson cautioned that "exclusive reliance upon

agency tbeory is imdesirable because tbe complexities of organizational life are ignored" (1997: 20).

Consistent witb tbese admonitions, tbe results of

. our meta-analyses do not support agency tbeory's

proposed relationsbip between ownersbip and firm

performance. Tbis is a significant finding, as

agency tbeory bas been cbaracterized as a tbeory of

tbe ownersbip structure of tbe firm (e.g., Jensen &

Meckling, 1976). Also, as we bave noted, agency

tbeory provides tbe tbeoretical foundation for tbe

vast majority of researcb conducted in corporate

governance (e.g., Sbleifer & Visbny, 1997).

Our results illustrate relatively low relationships

between various categories of equity and multiple

indicators of financial performance. In fairness, we

sbould add tbat the question of at what value a

correlation becomes important is an interesting

one. Rosenthal, Rosnow, and Rubin (2000) provided an illuminating treatment of how relatively

small effect sizes can bave critical consequences.

Consider tbe Fortune 500. To be placed in tbat

group, a company bas to bave at least $3 billion per

year in revenues; to be in tbe top 100 requires at

least $20 billion in revenues; and tbe top 10 average

Fehruary

over $130 billion in revenues. Relatively small effect sizes in revenue data from sucb firms could

represent many millions of dollars of gain or loss.

An Alternative Theoretical Lens: Substitution

Theory

For us, tbe results of our meta-analyses suggest tbe

need to consider alternative tbeoretical lenses for examining the ownership-performance relationship.

Other tbeoretical perspectives tbat bave been applied

to corporate governance researcb more generally include tbe legalistic perspective (e.g., Sbleifer &

Visbny, 1997; Zahra & Pearce, 1989) and stewardsbip

tbeory (e.g., Davis et al., 1997). Tbe legalistic perspective addresses tbe legal protections afforded sbareholders (Coffee, 1999; Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). bi tbe

face of managerial malfeasance, even minority sbarebolders are free to commence litigation (Coffee,

1999). Legal rights may dominate ownersbip concentration witbin tbis tbeoretical perspective. Stewardsbip tbeory focuses on explanations of why managers' interests would be aligned witb tbose of

shareholders (Davis et al., 1997). Within this theory,

organizational structures that facilitate managers'

power are preferred to those designed to constrain

managerial power. In fact, control is viewed as potentially counterproductive (Davis et al., 1997).

We propose an additional perspective based on the

substitution hypothesis (e.g., Rediker & Seth, 1995;

Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). Like agency theory, the

substitution bypotbesis focuses on issues surrounding tbe separation of ownership and control in public

corporations (Rediker & Setb, 1995). Scbolars taking

tbis perspective seek to explain tbe effectiveness of

various governance mecbanisms in limiting managerial opportunism. Wbereas agency tbeory addresses

the ability of governance mechanisms "to resolve the

shareholder-manager agency problem independent of

eacb otber," substitution tbeory addresses tbe relationsbips among alternative governance mecbanisms

(Rediker & Setb, 1995: 86; see also Agrawal & Knoeber, 1996; Demsetz, 1983).

Our proposed substitution theory approach is

analogous to contingency theory approaches that

have been applied to otber corporate governance

issues. Finkelstein and D'Aveni (1994), for example, concluded tbat a contingency approacb was

most suitable for explaining tbe adoption of tbe

leadersbip structure in wbicb one person is botb

CEO and board cbair. Relying on agency tbeory and

organization tbeory, tbey empirically establisbed

that CEO duality was more or less appropriate depending on tbe presence of certain contingent factors, sucb as CEO power and firm performance.

�2003

Dalton, Daily, Certo, and Roengpitya

They, too, concluded that agency theory, although

applicable, bas inberent limitations.

Some support for tbe presence of substitution effects is found in extant researcb (e.g., Agrawal &

Knoeber, 1996; Jensen, Solberg, & Zorn, 1992; Kocbbar, 1996; Moyer, Rao, & Sisneros, 1992; Rediker &

Seth, 1995). In view of our findings, we propose that

ownership structure is one governance mechanism to

be considered among a range of governance mecbanisms. Ownersbip categories may effectively substitute for anotber. Also, alternative governance mechanisms may substitute for ownersbip structure.

Could, for example, tbe expected relationsbip between CEO equity and financial performance be conditioned on tbe equity beld by other blockholders? A

CEO with a 5 percent equity position might bebave

very differently depending on wbetber other blockbolders beld, for example, 5 percent or 50 percent of

tbe remaining equity. One migbt also consider a simple two-by-two model addressing bigb/low equity

beld by officers and directors and bigb/low equity

beld by institutional holders (Atkinson and Galaskiewicz [1988] took a similar approach in the context of ownership patterns and corporate contributions). Would one expect differences in financial

performance among tbese four cells?

Limitations and Future Research Opportunities

Tbe inferential logic underlying the results we report is robust. The studies and observations reported

in Table 1 concern the largest firms in the United

States (drawn, for instance, from tbe Fortune 500, tbe

Standard & Poors 500, and tbe Forbes 500).^ Tbis

composition provides a distinct metbodological advantage, amounting to our baving a series of samples

drawnfiroma discrete population, with replacement.

It is tme that the exact elements of the population—

the largest corporations—cbange over time. Even so,

tbe fundamental nature of tbe population is invariant.

In Lykken's (1968) classic formulation, tbese studies

amoiuit to an extensive series of constructive replications. Time after time, researcbers, wbile relying on

different measurements of equity and performance in

varied contexts, bave investigated tbe equity-performance relationsbip.

However, sucb a sample also has a downside. Oiu"

results should be interpreted with some care as it

would not be appropriate to generalize our findings

beyond tbis specific sample. Although much of tbe

* For the overall test baseline, tbere were some samples comprised of smaller firms and four samples of the

largest banking groups. For Table 1, bowever, we omitted

these studies.

21

attention in strategic management, accounting, and

finance research, for example, is focused on this population of very large corporations, they comprise a

very small percentage of total business enterprise.

Tbe research we report in Table 1 does not include,

for example, initial public offerings (IPOs). Tbis may

be an area, however, wherein the equity of various

parties may be associated with IPO performance (e.g..

Booth & Cbua, 1996; Mikkelson, Partcb, & Sbah,

1997).

One of the limitations of meta-analytical procedures is that causality cannot be tested or imputed.

There are exceptions, as meta-analyses of studies

with causal experimental protocols can certainly be

syntbesized. Corporate governance researcb does

not have that character. For the meta-analyses on

which our results depend, however, causality is not

an issue because there is no indication of systematic relationships. Future research in this domain

could easily address these issues. A multiperiod

structural equations analysis, for instance, could

provide a longitudinal perspective on the results as

well as inform the discussion of causality.

Consideration of the potential for nonlinear relationships in the ownership-performance area may

also be fruitful. Tbe relatively modest empirical literatiu-e examining nonmonotonic relationsbips among

equity categorizations and performance measures

does not reflect a consensus view of tbe nature of

this relationship (e.g., Hermalin & Weisbacb, 1991;

McConnell & Servaes, 1990; Morck, Sbleifer, &

Visbny, 1988; Tbomsen & Pedersen, 2000). In tbe

next generation of research addressing relationships

between equity and performance, attention sbould be

given to tbe potential for nonlinear relationsbips.^

Conclusion

In tbeir review of the corporate governance literature, Shleifer and Vishny concluded tbat tbere are

"a variety of still open questions" in tbe field of

governance (1997: 774). One of tbe questions tbey

identified was wbetber the costs and benefits of

^ We were unable to provide a meta-analysis for a nonlinear relationship between equity and financial performance. The relatively few relevant studies were configured

in low, medium, and high categories of equity. In principle,

it would have been easy to provide a separate meta-analysis

for each, compare them with critical ratios, and determine,

in fact, if the estimated population correlations were statistically different. Unfortunately, there was no consensus

among the studies on what constituted the inflection points

across categories. Also, owing to the small niunber of samples in these categories, it would have been necessary to

rely on several financial perfonnance variables in concert.

�22

Academy of Management Journal

concentrated ownership are significant. Given the

centrality of ownership and performance issues in

corporate governance research, we are hopeful that

the results of the meta-analyses reported here, and

our discussion, will encourage further research

drawing on alternative theoretical approaches. In

particular, we encourage future researchers to consider the potential for governance mechanisms,

ownership or otherwise, to effectively substitute for

one another and/or operate in concert.

REFERENCES

February

intensity, relative mix, and economic determinants.

Joumal ofBusiness, 73: 661-693.

Gapon, N., Farley, J. U., & Hoenig, S. 1990. Determinants

of financial performance: A meta-analysis. Management Science, 36: 1143-1159.

Goase, R. 1937. The nature of the firm. Economica, 4:

386-405.

Goffee, J. G. 1991. Liquidity versus control: The institutional investor as corporate monitor. Columhia Law

Review, 91: 1277-1368.

Goffee, J. G. 1999. The future as history: The prospects for

global convergence in corporate governance and its

implications. Northwestern University Law Review, 93: 641-707.

Agrawal, A., & Knoeber, C. R. 1996. Firm performance

and mechanisms to control agency problems between managers and shareholders. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 31: 377-397.

Gollingwood, H. 2001. The earnings game: Everyone

plays, nobody wins. Harvard Business Review,

79(3): 65-74.

Alchian, A. A., & Demsetz, H. 1972. Production, information costs, and economic organizations. American Economic Review, 62: 777-795.

Gonference Board. 2000. Institutional investment report: Financial assets and equity holdings. New

York: Gonference Board.

Atkinson, L., & Galaskiewicz, J. 1988. Stock ownership

and company contributions to charity. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33: 82-100.

Gooper, H. 1998. Synthesizing research: A guide for

literature reviews. Thousand Oaks: GA: Sage.

Barnard, J. W. 1991. Institutional investors and the new

corporate governance. North Carolina LawReview,

69: 1135-1187.

Berle, A., & Means, G. 1932. The modem corporation

and private property. New York: Macmillan.

Bethel, J. E., & Liebeskind, J. 1993. The effects of ownership structure on corporate restructuring. Strategic

Management Journal, 14: 15-31.

Dalton, D. R., Daily, G. M., Ellstrand, A. E., & Johnson,

J. L. 1998. Meta-analytic reviews of board composition, leadership structure, and financial performance. Strategic Management Joumal, 19: 269290.

Dalton, D. R., Daily, G. M., Johnson, J. L., & Ellstrand,

A. E. 1999. Number of directors on the board and

financial performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of

Management Joumal, 42: 674-686.

Bethel, J. E., Liebeskind, J. P., & Opler, T. 1998. Block

share purchases and corporate performance. Journal

of Finance, 53: 605-634.

David, P., Kochhar, R., & Levitas, E. 1998. The effect of

institutional investors on the level and mix of GEO

compensation. Academy of Management Joumal,

41: 200-208.

Black, B. S. 1992. Agents watching agents: The promise

of institutional investor voice. UCLA Law Review,

39: 811-893.

Davis, G. F., & Thompson, T. A. 1994. A social movement

perspective on corporate control. Administrative

Science Quarterly, 39: 141-173.

Booth, J. R., & Ghua, L. 1996. Ownership dispersion,

costly information, and IPO underpricing. Journal of

Financial Economics, 41: 291-310.

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. 1997.

Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22: 20-47.

Borenstein, M. 1997. Comprehensive

Englewood, NJ: Biostat.

Demsetz, H. 1983. The structure of ownership and the

theory of the firm. Journal of Law & Economics, 26:

375-390.

meta-analysis.

Bothwell, J. L. 1980. Profitability, risk, and the separation

of ownership from control. Joumal of Industrial

Economics, 28: 303-311.

Boyd, B. K. 1991. Strategic planning and financial performance: A meta-analytical review. Joumal of

Management Studies, 28: 353-374.

Brickley, J. A., Lease, J. A., & Smith, G. W. 1988. Ownership structure and voting on antitakeover amendments. Journal of Financial Economics, 20: 267291.

Bryan, S., Hwang, L., & Lilien, S. 2000. GEO stock-based

compensation: An empirical analysis of incentive-

Demsetz, H., & Lehn, K. 1985. The structure of corporate

ownership: Gauses and consequences. Joumal of

Political Economy, 93: 1155-1177.

Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. Agency theory: An assessment

and review. Academy of Management Review, 14:

57-74.

Finkelstein, S., & D'Aveni, R. A. 1994. GEO duality as a

double-edged sword: How boards of directors balance entrenchment avoidance and unity of command. Academy of Management Joumal, 37:

1079-1108.

�2003

Dalton, Daily, Certo, and Roengpitya

23

Fromson, B. D. 1990. The big owners roar. Fortune, July

30: 66-78.

on equity ownership and corporate values. Joumal

of Financial Economics, 27: 595-612.

Hermalin, B. E., & Weisbach, M. S. 1991. The effects of

board composition and direct incentives on firm performance. Financial Management, 20(4): 101-122.

McGonnell, J. J., & Servaes, H. 1995. Equity ownership

and the two faces of debt. Journal of Financial Economics, 39: 131-157.

Himmelberg, G. P., Hubbard, R. G., & Palia, D. 1999.

Understanding the determinants of managerial ownership and the link between ownership and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 53: 353384.

Meyer, M. W., & Gupta, V. 1994. The performance paradox. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Gummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior: 309-369.

Greenwich, GT: JAI Press.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. 1990. Methods of metaanalysis: Correcting error and bias in research

findings. Beverly Hills, GA: Sage.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. 1994. Gorrecting for

sources of artificial variation across studies. In H.

Gooper & L. V. Hedges (Eds.). The handbook of

research synthesis: 324-336. New York: Russell

Sage Foundation.

Jensen, M. G. 1993. The modern industrial revolution,

exit, and the failure of internal control systems. Journal of Finance, 48: 831-880.

Jensen, M. G., & Meckling, W. H. 1976. Theory of the

firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3:

305-360.

Mikkelson, W. H., Partch, M. M., & Shah, K. 1997. Ownership and operating performance of companies that

go public. Joumal of Financial Economics, 44: 281307.

Morck, R., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. 1988. Managerial

ownership and market valuation. Joumal of Financial Economics, 20: 293-315.

Moyer, R. G., Rao, R., & Sisneros, P. M. 1992. Substitutes

for voting rights: Evidence from dual class recapitalizations. Financial Management, 21: 35—47.

Perry, T., & Zenner, M. 2000. GEO compensation in the

1990s: Shareholder alignment or shareholder expropriation? Wake Forest Law Review, 35: 123-152.

Pound, J. 1992. Beyond takeovers: Politics comes to

corporate control. Harvard Business Review, 70:

83-93.

Jensen, M. G., & Murphy, K. J. 1990. Performance pay and

top-management incentives. Joumal of Political

Economy, 98: 225-264.

Rediker, K. J., & Seth, A. 1995. Boards of directors and

substitution effects of alternative governance mechanisms. Strategic Management Joumal, 16: 85—99.

Jensen, G. R., Solberg, D. P., & Zorn, T. S. 1992. Simultaneous determination of insider ownership, debt,

and dividend policies. Journal of Financial and

Quantitative Analysis, 27: 247-263.

Rhoades, D. L., Rechner, P. L., & Sundaramurthy, G.

2000. Board composition and financial performance:

A meta-analysis ofthe influence of outside directors.

Joumal of Managerial Issues, 12: 76-91.

Kochhar, R. 1996. Explaining firm capital structure: The

role of agency theory vs. transaction cost economics.

Strategic Management Joumal, 17: 713-728.

Rosenberg, M. S., Adams, D. G., & Gurevitch, J. 2000.

MetaWin: Statistical software for meta-analysis.

Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.

Kochhar, R., & David, P. 1996. Institutional investors and

firm innovation: A test of competing hypotheses.

Strategic Management Joumal, 17: 73-84.

Rosenthal, R., & DiMatteo, M. R. 2001. Meta-analysis:

Recent developments in quantitative methods for

literature review. Annual Review of Psychology,

52: 59-82.

Kowlowsky, M., & Sagie, A. 1993. On the efficacy of

credibility intervals as indicators of moderator effects in meta-analytic research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14: 695-699.

Lane, P. J., Gannella, A. A., & Lubatkin, M. H. 1998.

Agency problems as antecedents to unrelated

mergers and diversification: Amihud and Lev reconsidered. Strategic Management Joumal, 19:

555-578.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. 2001. Practical metaanalysis. Thousand Oaks, GA.: Sage Publications.

Lykken, D. T. 1968. Statistical significance in psychological research. Psychological Bulletin, 70: 151-159.

Macey, J. R. 1997. Institutional investors and corporate

monitoring: A demand-side perspective. Managerial and Decision Economics, 18: 601—610.

McGonnell, J. J., & Servaes, H. 1990. Additional evidence

Rosenthal, R., Rosnow, R. L., & Rubin, D. B. 2000. Contrasts and effect sizes in behavioral research. Gambridge, England: Gambridge University Press.

Schwenk, G. R., & Shrader, G. B. 1993. Effects of formal

strategic planning on financial performance in small

firms: A meta-analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory &

Practice, 17: 53-64.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. 1997. A survey of corporate

governance."/ourna7 of Finance, 52: 737-783.

Short, H. 1994. Ownership, control, financial structure,

and the performance of firms. Journal of Economic

Surveys, 8: 203-249.

Smith, A. 1776/1952. An inquiry into the nature and

causes of the wealth of nations (R. M. Hutchins

[Ed.], Great books of the western world). Ghicago:

Encyclopedia Britannica.

�Academy of Management Journal

24

Sommer, A. A. 1990, Corporate governance in the nineties: Managers vs. institutions. University of Cincin-

February

_A)\

natHaw Review, 59: 357-383.

Thomsen, S,, & Pedersen, T, 2000. Ownership structure

and economic performance in the largest European

companies. Strategic Management Journal, 21:

689-705,

Useem, M, 1996. Investor capitalism: How money managers are changing the face of corporate America.

York: Basic Books.

Useem, M., Bowman, E. H,, Myatt, J,, & Irvine, C, W.

1993, U,S, institutional investors look at corporate

governance in the 1990s. European Management

Journal, 11: 175-189.

Wahal, S, 1996. Pension fund activism and firm performance. Journal of Financial and Quantitative

Analysis, 31: 1-23.

Walsh, J, P,, & Kosnik, R. D. 1993, Corporate raiders and

their disciplinary role in the market for corporate

control. Academy of Management Journal, 35:

671-700,

Zahra, S. A,, Neubaum, D, O,, & Huse, M. 2000. Entrepreneurship in medium size companies: Exploring

the effects of ownership and governance systems.

Journal of Management, 26: 947-976.

Zahra, S, A., & Pearce, J. A, 1989, Boards of directors and

corporate financial performance: A review and integrative model. Journal of Management, 15: 291334,

Dan R. Dalton (dalton@indiana.edu) is the dean and the

Harold A. Poling Chair of Strategic Management of the

Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. He received

his Ph,D, at the University of California, Irvine. Professor

Dalton's work focuses on corporate governance, particularly option repricing, equity holdings, stock-hased board

compensation, and initial public offerings (IPOs).

Catherine M. Daily is the David H, Jacohs Chair of Strategic Management in the Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. She received her Ph.D, in strategic

management from the Indiana University. Her research

interests include corporate governance, strategic leadership, the dynamics of husiness failure, ownership structures, and managerial ethics,

S. Trevis Certo received his Ph.D. in strategic management from the Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, and is now on the faculty at the Lowry Mays

College and Craduate School of Business, Texas A&M

University. His work has focused on corporate governance, with particular emphases on the examination of

initial puhlic offerings (IPOs), CEOs and top management

teams, and hoards of directors,

Rungpen Roengpitya is a doctoral student in strategic

management at the Kelley School of Business, Indiana

University. Her research interests are corporate equity

structures and international governance.

�2003

Dalton, Daily, Certo, and Roengpitya

25

APPENDIX

Articles Included in the Meta-Analyses"

Author

Year

Publication

Agrawal & Knoeber

Agrawal & Knoeber

Amihud, Lev, & Travlos

Ang, Cole, & Lin

Baliga, Moyer, & Rao

Balkin, Markman, & Gomez-Mejia

Barhnhart & Rosenstein

Bathaia

Bathaia, Moon, & Rao

Baysinger, Kosnik, & Turk

Beatty

Beatty & Zajac

Bergh

Bergstrom & Rydqvist

Berkman & Bradbury

Bethel & Liebeskind

Bhagat & Black

Bhagat, Carey, & Elson

Blasi, Conte, & Kruse

Boehmer

Boeker

Boeker

Boeker

Boeker & Coodstein

Bommer & Ellstrand

Borokhovich, Brunarski, & Parrino

Boyd

Brennan & Franks

Brook, Henderschott, & Lee

Brook, Hendershott, & Lee

Brous & Kini

Brush, Bromiley, & Hendrickx

Bryan, Hwang, & Lilien

Bucholtz & Rihbens

Byrd & Stammerjohan

Campsey & DeMong

Carlson & Bathaia

Carpenter

Carter & Manaster

Cebenoyan, Cooperman, & Register

Chaganti & Damanpour

Chang & Mayers

Chen & Jaggi

Cho

Claessens & Djankov

Clyde

Cochran, Wood, & Jones

Coles & Hesterly

Coles, McWilliams, & Sen

Conte & Tannenbaum

Conyon & Peck

Cotter & Zenner

Cubbin & Leech

Daily

Daily

Daily & Dalton

Daily & Johnson

Daily, Jobnson, Ellstrand, & Dalton

Datta & Rajagolpalan

David, Hitt, & Gimeno

David, Kochhar, & Levitas

Davis

Davis & Stout

Demsetz & Lehn

Denis, Denis, & Sarin

Dennis & Sarin

Dhillon & Ramirez

Dowen & Bauman

Duggal & Millar

Duggal & Millar

El-Gazzar

Elliott

Faccio & Lasfer

Filbeck

1996

1998

1990

2000

1996

2000

1998

1996

1994

1999

1989

1994

1995

1990

1996

1993

1999

1999

1996

2000

1989

1992

1997

1993

1996

1997

1994

1997

1998

2000

1994

2000

2000

1994

1997

1983

1997

2000

1990

1995

1991

1992

2000

1998

1999

1997

1985

2000

2001

1978

1998

1994

1986

1995

1996

1994

1997

1998

1998

2001

1998

1991

1992

1985

1997

1999

1994

1997

1994

1999

1998

1972

2000

1996

JFQA

JFE

JF

JF

SMJ

AMJ

FR

FR

FM

AMJ

AR

ASQ

SMJ

JBF

FM

SMJ

BL

BL

ILRR

JFl

ASQ

ASQ

ASQ

AMJ

GOM

JF

SMJ

JFE

JF

JCF

FM

SMJ

JB

AMJ

FR

RBER

JBFA

JM

JF

FM

SMJ

JFE

JAPP

JFE

JCE

MDE

AMJ

JM

JM

MLR

AMJ

JFE

MDE

JM

SMJ

AMJ

JM

AMJ

SMJ

AMJ

AMJ

ASQ

ASQ

JPE

JF

JFE

JBF

FR

QREF

JCF

AR

JFQA

JCF

QJBE

APPENDIX

Continued

Author

Finkelstein & Boyd

Finkelstein & D'Aveni

Finkelstein & Hambrick

Gamble

Geczy, Minton, & Scbrand

Gedajlovic & Shapiro

Glassman & Rhoades

Gomez-Mejia, Tosi, & Hinkin

Gompers & Lerner

Gorton & Rosen

Graves

Gray & Cannella

Had.lock, Houston, & Ryngaert

Han, Lee, & Suk

Han & Suk

Hanson & Song

Haushalter

Hayward & Boeker

Hajrward & Hambrick

Heflin & Shaw

Hermalin & Weisbach

Hill & Snell

Hill & Snell

Himmelberg, Hubbard, & Palia

Hirschey & Zaima

Hite & Vetsuypens

Hodrick

Hoiderness & Sheehan

Holl

Hoii

Hoskisson, Johnson, & Moesel

Hoskisson & Johnson

Hudson, Jahera, & Lloyd

Jain & Kini

James & Wier

Jarreii & Poulsen

Johnson, Hoskisson, & Hitt

Jones, Lee, & Thompkins

Kamerschen

Kamerschen & Paul

Ke, Petroni, & Safieddine

Keloharju & Kulp

Kerr & Kren

Kesner

Kim, Krinsky, & Lee

Kim, Lee, & Francis

Kini & Mian

Klassen

Klein

Knopf & Teali

Krause

Kren & KenLane, Cannella, & Lubatkin

Lang, Stulz, & Walkling

Lange & Sharpe

Leweilen, Loderer, & Rosenfeld

Li & Simeriy

Lin

Livingston & Henry

Madden

Mahoney, Sundaramurthy, &

Mahoney

Maksimovic & Unal

Mallette & Fowler

Mallete & Hogler

McBain & Krause

McConneil & Servaes

McEachern

McKean & Kania

McWilliams & Sen

Mehran

Mehran

Mikkelson, Partch, & Shah

Mishra & Nielsen

Year

Publication

1998

1994

1989

2000

1997

1998

1980

1987

1999

1995

1988

1997

1999

1999

1998

2000

2000

1998

1997

2000

1991

1988

1989

1999

1989

1989

1999

1988

1975

1977

1994

1992

1992

1994

1990

1988

1993

1997

1968

1971

1999

1996

1992

1987

1997

1988

1995

1997

1998

1996

1986

1997

1998

1991

1995

1989

1998

1996

1980

1982

1997

AMJ

AMJ

SMJ

JBV

JF

SMJ

RES

AMJ

JLE

1993

1992

1995

1989

1990

1978

1978

1997

1992

1995

1997

2000

JF

AMJ

JM

JBV

JFE

JIE

JB

JFQA

JFQA

JFE

JFE

FM

JF

AMJ

JM

JBF

MBR

RFE

JCF

JF

ASQ

ASQ

JFQA

FM

AMJ

AMJ

JFE

JF

JF

JFE

JFE

JIE

JIE

AMJ

SMJ

FR

JF

JFE

JFE

SMJ

MDE

AER

MIR

JAE

JBF

AMJ

JM

JAAF

FR

JFR

AR

JLE

JBF

JBE

ABR

SMJ

JFE

AFE

JFQA

SMJ

NULR

JRI

JEB

MDE

�Academy of Management Journal

26

February

APPENDIX

Continued

APPENDIX

Continued

Publication

Author

Author

Year

Mizrucbi & Stearns

Moh'd, Perry, & Rimbey

Moh'd, Perry, & Rimbey

Molz

Morck, Nakumura, & Shivadasani

Morck, Shieifer, & Vishny

Mudambi & Nicosia

Muraii & Welch

Neun & Santerre

O'Reilly, Main, & Crystal

Palia & Licbtenbert

Palmer, Jennings, & Zhou

Peck

Peng & Luo

Pi & Timme

Porac, Wade, & Pollock

Pouder & Cantreii

Prowse

Raad & Reinganum

Radice

Ramaswamy, Veiiyath, & Gomes

Rosenstein & Wyatt

Round

Ruef & Scott

Safieddine & Titman

Saiancik & Pfeffer

Sanders & Carpenter

Santerre & Nuen

Schoonhoven, Eisenhardt, &

Lyman

Short & Keasey

Simpson & Gleason

Singh & Harianto

Singh & Harianto

Slovin & Sushka

Smith & Amoako-Adu

Song & Walkiing

Sorenson

Stano

Steer & Cable

Steiner

Stigler & Friedland

Sundaramurthy

Sundaramurthy & Lyon

Sundaramurthy, Mahoney, &

Mahoney

Sundaramurthy & Rechner

Sundaramurthy, Rechner, & Wang

Szewczyk & Tsetsekos

Szewczyk, Tsetsekos, & Varma

Thomsen & Pedersen

Thonet & Pensgen

Tkac

Tosi & Gomez-Mejia

Trostel & Nichols

Tsetsekos & DeFuso

Utama & Cready

Vafeas

Vafeas

Vernon

Vijh

Wade; O'Reilly, & Ghandratat

Ware

Wedig, Sloan, Hassan, & Morrissey

Werner & Tosi

Westphai

Westphal

Westphai & Milton

Westphai & Zajac

Westphal & Zajac

Wruck

Yermack

Yermack

1994

1995

1998

1988

2000

1988

1998

1989

1986

1988

1999

1993

1996

2000

1993

1999

1999

1992

1995

1971

2000

1997

1976

1998

1999

1980

1998

1993

1990

ASQ

FR

FR

JBR

JB

JFE

AFE

Zahra

Zahra, Neubaum, & Huse

Zajac & Westphai

Zajac & Westphai

Zajac & Westphal

Zeitlin & Norich

JBFA

1999

1999

1989a

1989b

1993

1999

1993

1974

1975

1978

1996

1983

1996

1998

1997

JCF

" Abbreviations for the journals are as follows: ABR: Accounting and Business Research; AER: American Economic Review;

AFE; Applied Financial Economics; AMJ: Academy of Management Journal; AR: Accounting Review; ASQ: Administrative Science Quarterly; BL; Business Lawyer; BS; Business and Society;

EI; Economic Inquiry; EJ; Economic Journal; FM; Financial Management; FR; Financial Review; GOM: Group and Organization

Management; ILRR; Industrial and Labor Relations Review;

IREF; International Review of Economics and Finance; JAAF;

Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance; JAE; Journal of

Accounting and Economics; JAPP: Journal of Accounting and

Public Policy; JB; Journal ofBusiness; JBE; Journal of Behavioral

Economics; JBF; Journal of Banking and Finance; JBFA; Journal

of Business, Finance, and Accounting; JBR: Journal of Business

Research; JBS: Journal of Business Strategies; JBV: Journal of

Business Venturing; JCE; Journal of Comparative Economics;

JCF; Journal of Corporate Finance; JEB; Journal of Economics

and Business; JIE; Journal of Industrial Economics; JF; Journal of

Finance; JFE; Journal of Financial Economics; JFl; Journal of

Financial Intermediation; JFQA: Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis; JFR; Journal of Financial Research; JLE; Journal of Law and Economics; JM: Journal of Management; JMI;

Journal of Managerial Issues; JPE; Journal of Political Economy;

JPM: Journal of Portfolio Management; JRI; Journal of Risk and

Insurance; MBR: Multinational Business Review; MDE; Managerial and Decision Economics; MIR; Management International

Review; MLR; Monthly Labor Review; NULR: Northwestern University Law Review; QJBE; Quarterly Journal of Business and

Economics; QREB; Quarterly Review of Economics and Business; QREF; Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance; RBER;

Review of Business and Economic Research; RES: Review of

Economics and Statistics; RFE; Review of Financial Economics;

RIDSEC; Rivista Internazionale Di Scienze Economiche e Commercial; RPE; Research in Political Economy; SEJ; Southern

Economic Journal; SMJ; Strategic Management Journal.

1997

1996

1993

1992

2000

1979

1999

1994

1982

1990

1997

1999

2000

1971

1999

1990

1975

1988

1995

1998

1999

2000

1995

1997

1989

1996

1995

MDE

ASQ

JCF

ASQ

JFE

AMJ

JBF

ASQ

JBS

JF

FM

EJ

MIR

JFE

RIDSEC

ASQ

JF

AMJ

AMJ

EI

ASQ

IREF

AMJ

SMJ

JF

JCF

JFQA

SEJ

SEJ

JIE

QJBE

JLE

SMJ

JMI

SMJ

BS

JM

FR

FR

SMJ

JIE

JFQA

AMJ

AMJ

JPM

JAE

JFE

JAPP

JFQA

JFE

ASQ

QREB

JF

AMJ

ASQ

AMJ

ASQ

ASQ

ASQ

JFE

JFE

JFE

Year

Puhlication

1996

2000

1994

1995

1996

1979

AMJ

JM

SMJ

ASQ

AMJ

RPE

��

Raghuvaran A P

Raghuvaran A P