Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2008, volume 26, pages 1115 ^ 1130

doi:10.1068/d6307

Abusing multiculturalism: the politics of recognition and land

allocation in Israel À

Erez Tzfadia

Department of Public Policy and Administration, Sapir College, D N Hof Ashkelon 79165, Israel;

e-mail: erezt@mail.sapir.ac.il

Received 25 July 2007; in revised form 23 August 2008

Abstract. The logic behind land allocation for residential purposes has undergone a dramatic shift

in many states with a colonial legacy in the recent decade, from an ethnonational logic that favors

the ethnonational majority to a more liberal-democratic, market-based logic that disregards ethnicity.

In Israel, following this shift, a new claim for biased allocation has been voiced by the ethnonational

majority, politicians, and administrators, which is based on multiculturalism and recognition. According to this claim, land allocation should serve the communal needs of the majority by limiting the

access of minority groups to the majority group's residential areas. In this paper I argue that, despite

the decline of ethnonationalism, the discourse of multiculturalism remains a substitute discourse that

rationalizes the interests of the majority group, hence contributing to the stratification of societies on

the basis of ethnicity. Through an analysis of three case studies of land allocation in Israel, the

paper explores the material and cultural weaknesses of a multiculturalism that has been imported

from societies with a strong liberal-democratic tradition into societies with a profound ethnonational

legacy.

Introduction

``(a) State land shall remain under state ownership.

(b) Land shall be allocated by the state according to the law.

(c) Land shall be expropriated in keeping with the law, in exchange for adequate

compensation.

(d) The state shall develop its resources for the good of all its citizens. Land allocation

shall respect the lifestyle of distinct communities.''

In June of 2005, in the framework of discussions on a `consensual constitution', the

Israeli Parliament's Constitution, Law and Justice Committee debated impending

land legislation, focusing on the above reference, which was proposed as the paragraph pertaining to land in a future Israeli constitution. (1) Israeli legal authority

Professor Ruth Gavison labeled it a ``neutral paragraph ... because it does not indicate that Israel is the state in which the Jewish nation realizes its sovereignty''

(Gavison and Greidi-Schwartz, 2005). (2) Her claim is relevant to section (d), which

promises to ``respect the lifestyle of distinct communities'' associatively related to

multiculturalism ö that is, to grant all communities recognition, supported by land

allocation. The above passage and Gavison's remark serve as a preface to this paper,

which focuses on the current discourse of recognition and public land allocation

À Early versions of this paper were presented at the Humphrey seminar at Ben-Gurion University,

Israel (2006) and at `Beyond the Nation' ö a conference held at Queen's University, Belfast

(2007).

(1) In

recent years the Knesset's Constitution, Law and Justice Committee has endeavored to adopt

a `Broad-based Consensual Constitution'. This attempt is based on a deliberation process that

includes think tanks and scholars (see Gavison, 2003).

(2) All the quotations in this paper are translated from Hebrew by myself.

�1116

E Tzfadia

for housing in Israel.(3) I do not focus here on land in the occupied territories, where

the logic of ethnonationalism has never been challenged. Through the prism of these

two passages, the paper contributes to the debate about multiculturalism by examining what happens in the field of land allocation when multiculturalist theory is put

into practice in societies that are founded on substantial ethnonational logic.

Over the past three decades the legitimacy of allocating land inequitably according

to ethnonational logic has declined in many states with a colonial legacy, such as

Australia and Canada. This legitimacy has been replaced by a liberal-democratic

agenda, and most recently by the substitute agenda of multiculturalism. One particular

arena in which these changes have taken place is that of recognizing the land rights

of indigenous peoples after hundreds of years of white ethnicization, which itself

was based upon the concept of terra nullius (Anderson, 2000; Harris, 2004). The

concentration of aborigines into reserves or specific neighborhoods drove them off

their land and away from their traditional ways of life, yet it assisted in the preservation of their identities and provided a platform for mobilization. Following a series

of broken promises, many states with a colonial legacy have adopted some symbolic

and concrete policies of contrition during the past three decades, which are encapsulated in the agenda of multiculturalism. These include `native land' rights (Colin, 1993;

Moran, 2002), which in Canada have provided self-control over the First Nation's

territory and its natural resources as part of the policy of self-government over its

religious, cultural, economic, and political life (Colin, 1993). In Australia, the Aborigines are given the title of `native', through developing, participating in, and promoting

the statewide indigenous land-use agreement process (Agius et al, 2007).

Since the mid-1990s Israeli scholars have argued that the ethnonational legitimacy

of allocating land inequitably has declined in Israel as well (Shafir and Peled, 1998).(4)

This decline is evidenced in the emerging of multicultural discourse and nonofficial

practices in education (Al-Haj, 2002), in local authorities (Tzfadia and Yacobi, 2007),

and partly in immigration policy (Kimmerling, 2001). The above-quoted land passage

is another expression in the field of land and planning. It recognizes the right of

minorities, who are citizens of the state of Israel, to enjoy separate areas of residency

of their own will, even if this means selecting residents on the basis of ethnicity

(Imbroscio, 2004) rather than according to the liberal-democratic agenda. In this paper

(3) Public

land in Israel is usually referred to as the `Land of Israel', and comprises 93% of all land

in the country. It is property of either the state, the Jewish National Fund (JNF, which was founded

in 1901 by the Zionist Congress to buy and develop land in Palestine for Jewish settlement), or the

Development Authority (which holds the land of all Palestinian refugees registered as `absent'). In

1961, the state of Israel and the JNF agreed that the 2.5 million dunams (1 dunam 0.25 acre) of

land owned by the JNF (which is 14% of the land in Israel) would serve only Jews, as part of the

ethnonational Jewish settlement project. All public land in Israel, including that owned by the JNF,

is administered by the Israel Land Authority (ILA) and the Israel Land Council (ILC), which

determines the policy of the ILA. This large share of public land is important for new housing

projects, as most of the development takes place on public land.

(4) It should be clear that this change has been limited to land allocation within Israel and has

been limited only to Israeli citizens ö both Jews and Palestinians. Thus it seems to go against

the expansion of settlements in the West Bank, the transformation of East Jerusalem, and the

Separation Wall. Palestinians in the occupied territories have not been granted Israeli citizenship,

thus preventing any resource allocation rights. Furthermore, the occupied territories and the

Palestinians are subject to a military regime and are not under Israeli jurisdiction. This fact gives

space for some Jewish settlement movements such as Gush Emunim to advance Palestinianowned land expropriation and to build new settlements outside the Israeli legal framework

(see Newman, 2005). For these reasons, the paper avoids discussion on the occupied territories.

Nevertheless, the occupation cannot be disregarded when ethnonationalism is confronted (see

Yiftachel, 2006).

�Abusing multiculturalism: the politics of land allocation in Israel

1117

I argue that, despite the apparent decline of ethnonationalism, multiculturalism is

combined with an enduring ethnonational project of nation building and state formation. Multicultural rhetoric is used to secure the hegemonic position of the majority,

instead of protecting minorities from assimilation in a melting pot. Thus, multiculturalism does not offer an alternative project that needs ``to be articulated in political

terms in relation to other axes of social stratification having to do with race, class,

gender, sexuality and nation'' (Shohat and Stam, 2003, page 7).

My research shows that, in societies founded on substantial ethnonational logic,

multicultural terminologyömainly the discourse of recognition öactually rationalizes

the interests of the ethnonational majority. In Israel this majority refers first and

foremost to its secular-European sector (Kimmerling, 2001). In the field of land allocation, this sector demands the recognition that multiculturalism attempts to grant

to minorities, thus preventing members of minority communities from attaining equal

access to newly established gated communities. In general, dominant majorities abuse

the discourse of recognition and communality in order to limit the freedom of minorities in the housing market. And the sociospatial practice of separateness creates

another barrier to tolerance of diverse cultural/ethnic/social groups.

Here lies the weakness of the discourse of recognition embedded in multiculturalism when it is imported from societies with strong liberal-democratic bases to

those with strong ethnonational bases: the discourse of recognition in these societies

maintains a stratified social structure, but without the antagonism stimulated by

ethnonationalism. Thus, in contrast to Anderson's (1998) `sites of difference' or Fincher

and Jacobs's (1998) `cities of difference', which endorse cultural differences, this paper

explores how claims to recognition become a practice of exclusion when made by

a dominant group. In other words, my paper seeks to challenge the moral grounds

of multiculturalism and to portray the discourse of multiculturalism as a new politics

that privileges dominant ethnonational communities.

Other researchers have already explored the links between the ethnonational past

and multiculturalism. Anderson (1991) examines the way in which orientalist conceptions of the Chinese minority in Canada and Australia have structured the responses

of those countries' Anglo elite. Anderson (1998) claims that there is continuity between

the 19th-century ideologies of white ethnonationalism and the late-20th-century

ideologies of state multiculturalism. Although they are superficially quite different,

they both embody an essentialist attitude toward the Chinese minority. In earlier times,

this was a racial essentialism; in more modern times, it is cultural. Yuval-Davis (1997)

also explains that multiculturalism in contemporary liberal democracies is subject

to limits, such as the predominance of existing nation-state languages, the legitimating

of ruling cultural practices, and the hegemony of official political cultures.

My research also reveals the connections between ethnonationalism and multiculturalism, and in this sense it further develops Yiftachel's (2006) ethnocratic

model. In contrast to Anderson (1991; 1998) and Yuval-Davis (1997), I emphasize

materialistic rather than cultural aspects of multiculturalism, and analyze the upper

(and `white') strata of society (5) rather than lower strata ö that is, how the (ab)use

of multiculturalism maintains the materialistic interests of groups who have been

privileged by ethnonationalism. In this sense, my research continues the debate

about the links between multiculturalism and material inequality, regarding the old

question of politics as `who gets what?'.

(5) Reitman

(2006) makes a similar connection between multiculturalism and whiteness in high-tech

workplaces.

�1118

E Tzfadia

Supporters of the multicultural project regard multiculturalism as a device for

decreasing inequality. Banting and Kymlicka (2004), for example, find that, in the

OECD countries, multicultural policy and social redistribution are integrated: as

countries intensify their multicultural policies, social inequality is mitigated. Many

other researchers agree that there is a positive link between multiculturalism and

equality, mainly in terms of recognition and distribution because ``the achievement of

recognition itself redistributes the opportunity of citizens to gain economic and political power'' (Tully, 2000, page 470). The followers of the traditional Marxist approach,

on the other hand, claim that the struggle to achieve recognition disrupts the classbased struggle for equal distribution (Wilensky, 1975 in Banting, 2005). This criticism

is inspired by Jameson's `cultural logic of late capitalism' (1984), and views multiculturalism as the new politics of dominant groups to reduce the effect of claims for

redistribution made by racial and ethnic groups. However, I argue that this politics

should not be seen as class-based conflict, but, rather, as ethnonational-based conflict.

Following the criticism of multiculturalism and redistribution, and Anderson's

(1991) critique on the relations between ethnonationalism and multiculturalism, my

research proposes a new dimension of criticism on multiculturalism. It examines how

Fraser's (2003) `perspectival dualism', a common framework for redistribution and

recognition, is practiced at the top of the social hierarchy in order to maintain the

kind of biased allocation of land resources that was typical of the ethnonational past.

To this aim, the paper will briefly present the decline in the legitimacy of ethnonational-based biased allocation in Israel, and the emergence of characteristics of

liberal-democratic and multicultural models, mainly in relation to land allocation

policy. Three case studies on communality and land allocation will be subsequently

analyzed.

Models of citizenship and land allocation: Israel in context

Since the early days of statehood, ethnonationalism has served as the leading model

for citizenship in Israel.(6) Every citizen possesses democratic rights, including the right

to vote and organize political parties. However, one ethnonational community is in

a dominant position and is clearly privileged over the other(s). This community can

maintain exclusive control of the state within formally democratic institutions and

monopolize political power for its own interests. The sense of belonging to a particular

territory, into which the ethnonational community is socialized, produces and reproduces exclusiveness, which is the core of social interactions (Murphy, 2002; Penrose,

2002; Storey, 2001). Ethnonational communities appropriate land resources, because

the instrumental power of land establishes sovereignty, property rights, and jurisdiction.

Spatial nationalization, usually realized by land expropriation and allocation for settling

members of the ethnonational community, is a key practice in `territorial accumulation'

at all geographical levels: urban, regional, and national (Yiftachel, 2006). This accumulation rests primarily on physical power and the supporting infrastructure of the

state (Harris, 2004). At the same time, it is a fundamental basis for social stratification

according to ethnicity, as the allocation of land for settlement is translated into private

property belonging to the members of the ethnonational community.

As Forman and Kedar (2004) described, since 1948, Israel has constructed a

property regime by which the state gained control over 90% of the land in the country

through land acquisition and the dispossession of Palestinian refugees and Palestinians

(6) This

is a typical description of the Israeli society and space (see Yiftachel and Yacobi, 2003).

In recent years, Israeli scholars have analyzed the roots behind ethnonationalism (see, for example,

Kimmerling, 2001; Shafir and Peled, 2002; Yiftachel, 2006).

�Abusing multiculturalism: the politics of land allocation in Israel

1119

who remained and became Israeli citizens. A parallel effort was made to establish

new settlements for Jews, mainly in regions where Palestinians made up the majority,

such as the Galilee, the Negev, and, since 1967, the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Jewish

settlement was portrayed as part of the contribution to the `nation-building project',

through the defense of the state's borders and control of `national land' (Shafir

and Peled, 2002). Thus ethnonational discourse and practice formed `rigid' social

and geographic boundaries between Jews and Palestinians, because only Jews could

`contribute' to the settlement project, and hence benefit from biased land allocation

for settlement. More `flexible' boundaries were created within Jewish society, corresponding with the extent to which `national' identity has been adopted (ie through the

cultural norms of a particular community within the Jewish society öthe Europeansecular group, usually identified as Ashkenazim. Ashkenazim have enjoyed control

over most land resources, in preferred locations and with a higher standard of infrastructure. Jewish immigrants from Muslim countries (Mizrahim) and recently from the

former Soviet Union (`Russians') rarely gained access to prestigious Ashkenazi settlements and suburbs. Thus, land allocation, mainly for settlements in frontier and

internal frontier regions, contributed greatly to ethnoclass stratification between Jews

and Arabs and within Jewish society, correlating with ethnicity (Shafir and Peled, 2002;

Yiftachel, 2006).

In recent years, ethnonational land allocation has been limited in Israel, as well as

in other states with colonial legacy, because of a reconceptualization of the preferred

spatial development. There is now a shift from territorial control to economic globalization and growth, from `frontier settlement' to `urbanization'. New regulations and

policies and a new planning approach have been launched, restricting the allocation

of land for new settlements, limiting suburbanization or residential expansion of

rural settlements, and fostering entrepreneurial spatial development (Shachar, 1998).

Many Israeli planners and social scientists argue that these modifications, which are

evidenced in Israel but not in the occupied territories, go hand-in-hand with the gradual

weakening of Israeli national and territorial collectivist ideology, as well as with an

atmosphere of peace in the Middle East (Ram, 2004). They also present Israeli society

with a new model of citizenship: liberal democracy (Shafir and Peled, 1998).

A liberal democracy upholds the ideal of equal and undifferentiated citizenship, in

which individuals are free to practice their culture or religion privately or communally.

The liberal-democratic state's key institutional device is a bill of rights that outlaws

discrimination against individuals, including discrimination on the basis of ethnicity

or race. Accordingly, states are to treat all citizens equally, including in the provision

of equal economic assistance (Barry, 2002). In terms of housing, many countries have

implemented the legislation of fair housing laws and antidiscrimination, civil rights

provisions that prohibit the denial of access to housing to persons of color or to single

women, for example, because of who they are. Undoubtedly, residential segregation

continues to thrive in cities and suburbs, but now, it is argued, largely driven by market

forces and marked by class division rather than by race or ethnicity.

The symbolic moment of decline of ethnonationalism in Israel in the field of land

allocation was in 2000, when the Israeli High Court announced its ruling in Case 6695/95,

known as the `Qa'adan ^ Katzir ruling'. Husband and wife Adel and Iman Qa'adan,

Palestinian citizens of Israel, made a request to purchase a plot of land in the new Jewish

communal settlement of Katzir in order to build a home (Barry, 2002). They were

refused by the admissions committee based on an official policy prohibiting the sale of

plots in the newly established Jewish settlement to non-Jews. The High Court recommended that the state of Israel reconsider the institutional procedures that deny Arabs

equal land allocation in newly established `Jewish' settlements (Shamir and Ziv, 2001).

�1120

E Tzfadia

Israeli scholars suggested that the ruling called upon the state to replace ethnonational

criteria for land allocation with liberal-democratic criteria. In effect, the ruling created

a clear distinction between the private sphere and the national sphere, in which the

state must assure equality in land allocation to all citizens (Kedar, 2000).

The ruling has been criticized by people on both ends of the academic and political

spectrum. On the one hand, many loyalists of the ethnonational model, scholars, and

parliament members have maintained that, because the Jews are a minority in the

Middle East, the Jewish State must protect its own interestsöto be precise, those of

its dominant ethnonational community öeven if this contradicts norms of equality.(7)

On the other hand, devotees of the multicultural model have argued that the High

Court did not concern itself with the communal needs of the Palestinian minority

in Israel. Instead of instructing the state to allocate land for building Palestinian

communal settlements in which the Palestinians may maintain their culture and

nationality, the High Court proposed integrating Palestinian individuals within Jewish

communities. Thus Palestinians who choose to improve their standard of living by

moving to new suburbs become a minority in Jewish communities, abandoning their

Palestinian culture (Jabareen, 2000).

The difference between liberal-democratic jurisprudence and the multicultural critique

should be highlighted in relation to land allocation. While standard liberal democracy is

founded on the notion of individual equality, multicultural liberal democracy is based on

individual equality, along with moderate protection for cultural communities. While a

liberal democracy takes steps to protect individual rights, a multicultural liberal democracy takes additional steps to protect the culture of minority communities and to shield

at least some aspects of their culture from assimilation. Such steps may express empathy

with minority rightsöif they so desireöto create geographical enclaves where they can

preserve and practice their unique cultures (Qadeer, 2003).

Indeed, there is a debate in the field of multiculturalism and planning about

whether homogenous enclaves serve the ideal of multiculturalism. The roots of the

debate lie in the fertile literature on residential segregation, the reasons behind it,

and its effects (Van Kempen and Ozuekren, 1998). The debate in the field of multiculturalism examines the costs and benefits of ethnic residential segregation, where the

costs are that it impedes social equity and fair access to wealth, and the benefits are

that it supports group rights concerning the preservation of their heritage and identity,

as well as economic advantages that result from the strength of the area's social,

cultural, and economic networks (Qadeer, 2003; 2005). In Canada, for example, the

group rights of ethnic communities give a new meaning to their residential concentration. Yet, Canadian law prevents any expression of discrimination in the housing

market, thus avoiding allocation of land for ethnic clustering (Qadeer, 2003). In other

places, such as Australia, the planning authorities exploit the antidiscrimination legislation to prevent ethnic enclaves in central cities of less-desired communities such

as Buddhists and Muslims (Sandercock, 2000).

Yonah (2005) questions when segregation should be encouraged in multicultural

societies: when there is a high level of cultural openness between groups as well as

a high level of mutual closeness, this reflects a social reality where the uniqueness of

the groups' cultures and lifestyles is not that deep, so they are able to find a broad

common cultural denominator that is given expression in their ability to share

joint residential spaces. Conversely, the higher the level of cultural introversion in the

groups and the higher the mutual distancing, the more the multicultural project will be

(7) See,

for example, Shetreet (2003), who represents a moderate voice among the ethnonational

critique on the Qaadan ^ Ketzir ruling.

�Abusing multiculturalism: the politics of land allocation in Israel

1121

expressed by enclaves. Unlike Yonah, Jabareen (2000) avoids the question of the level

of openness/introversion. Rather he suggests that indigenous people should enjoy

public land allocation to maintain ethnic enclaves, while immigrant communities

should not.

Jabareen's (2000) sociolegal critiqueöassociated with the multicultural model,

offers a substitute operative proposal to the `Qa'adan ^ Katzir ruling', which calls for

the separate allocation of land to Jews and Arabs for new settlements, thereby enabling

each community to preserve its own culture within a communal setting. A more radical

version of this critique, which is based on the idea that multiculturalism aims to

protect minorities' cultural rights, maintains that the dominant group öthat is, uppermiddle-class secular Jewsöshould not benefit from this arrangement. This group,

it is argued, does not need communal spaces such as gated communities in order to

preserve its culture, because Israel is already defined by secular Jews' cultural preferences. This ethnonational group has benefited from generous land allocation, with a

range of housing options available to its members. In other words, the radical version

of multiculturalism undermines both the ethnonational and the liberal-democratic

logics, proposing instead to resolve historical injustices, both distributional and cultural,

by employing a new spatial and communal policy (Benvenisti, 1998).

The High Court's challenge to the ethnonational model has symbolic significance.

When it was published, the ruling's implications were not clear. It was assumed that

the court ruling would bring about change in a complex sociopolitical reality. Following the ruling, however, usage of multicultural discourse has, indeed, become more

prevalent in Israel. The `catch' is that this discourse has been employed not only by

minorities, but also by the Jewish-secular majority in order to ensure biased resource

allocation, as was common in the pre-Qa'adan ^ Katzir period. Following the ruling,

several petitions were made by Jews and Arabs who were rejected by admission

committees of suburbs, but most of them were resolved before the court made a

decision because the admission committees were concerned that the court would

reconfirm the Qa'adan ^ Katzir ruling. In the years 2004 ^ 07, a dozen articles were

published on this matter in the daily newspaper Ha'aretz öall of which seem to be

biased against the idea of communality. A new NGO was established in the Galilee,

calling to halt the process of biased land allocation for housing. (8) It seems that land

allocation and communality are being debated seriously in Israel. (9)

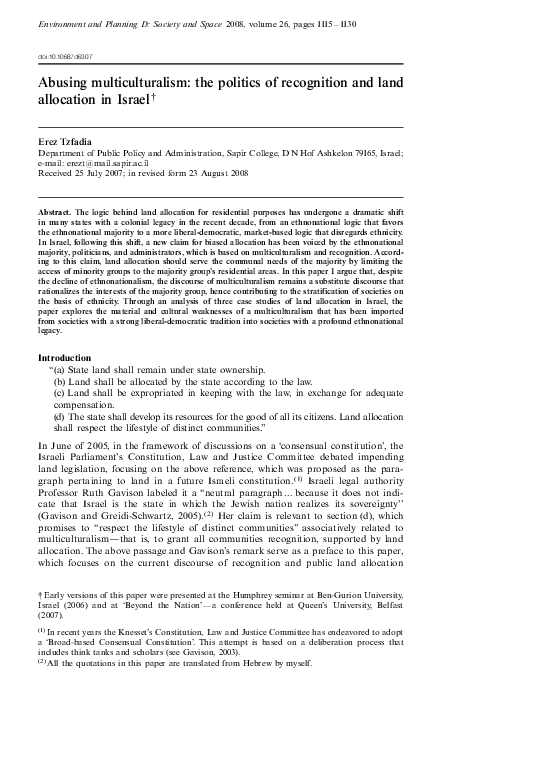

The three cases presented and analyzed hereafter illustrate different aspects of the

abuse of multiculturalism: the first illustrating the ethnonational argument against

Arabs, the second focusing on the abuse within the Jewish society, and the third

illustrating the abuse directed against all `Others' (see figure 1). These are not representative cases: these cases were debated in court and in the media, and, in this sense,

selection of these three cases is biased. Use of juridical documents and news reports

does, however, simplify the attempt to conduct a profound analysis. Methodologically,

the analysis of the cases brings together data from three major sources: (a) official

planning instructions, as published on the website of the ILA (http://www.mmi.gov.il);

(b) documentation of juridical processes, primarily petitions by individuals offended

by land allocation; and (c) all the reports on these cases that have been published

in the national newspaper Ha'aretz. All the documents were analyzed thematically.

The themes that served the document analysis were: ethnonationalism, liberalism, and

multiculturalism.

(8) The

NGO's name is `Alternative Voice in the Galilee' (see http://alternative-voice.org).

addition, a new documentary film in Hebrew on this issue Perfect Family, was presented on

television (see http://yes.walla.co.il/?w=2/7801/1156824). Several conferences in law schools have

focused on this issue as well.

(9) In

�1122

E Tzfadia

N

Major city

Case study

0 10 20 km

Figure 1. Location of case studies.

�Abusing multiculturalism: the politics of land allocation in Israel

1123

Givat-Makosh in Carmiel

In March of 1997 the official planning institutions approved a plan for the Givat

Makosh neighborhood (section b) to be built in the town of Carmiel.(10) The plan

facilitated construction of the new neighborhood on 594 dunams, with a total of 677

housing units, mostly single-family units. In April of 2004 the ILA issued a public

tender for marketing 43 lots for self-construction of single housing in the neighborhood.(11) Six Arab families won the tender, which upset the Jewish buyers: many of the

Jewish buyers were longtime Carmiel residents who saw the new neighborhood as

an opportunity to improve their standard of living in an attractive communal area

surrounded by the beautiful Galilee mountains, and they were concerned about the

significance of their new neighbors. Carmiel Mayor Adi Eldar joined the voices of

the opposition, claiming that, if Arab families lived in Givat-Makosh, ``Jewish ^ Arab

relations in the region might suffer'' (quoted in Khoury, 2004a).

Carmiel is a Jewish town located in the mixed Jewish ^ Arab Galilee region, with

41 000 residents (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2003, pages 180 ^ 181). Since 1948, and as

part of the ethnonational logic, the Galilee has been a target for the Judaization policy

aimed at achieving a demographic balance in favor of Jews (Khamaissi, 2003). As part

of this project, Carmiel was established in the 1960s on expropriated Palestinian-owned

land, in a dense Arab area, bordering four Arab towns, yet kept segregated from them.

As a result of the protest of the Jewish families in Givat-Makosh and Mayor

Eldar's opposition, the ILA froze the tender on the grounds that the land belonged

to the JNF and thus could be leased only to Jews (see footnote 3). Three months later,

the ILA announced a new tender for marketing the lots in the neighborhood, this time

adding that ``the land is owned by the JNF, hence subject to the contract between

the state and the JNF'',(12) meaning the land was available to Jews only.

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI) and the Arab Alternative Planning

Center (AAPC) petitioned the District Court, demanding Arab citizens be allowed to

participate in the ILA tender.(13) The ILA chose to cancel the entire tender, forcing the

court to withdraw the petition (Khoury, 2004b). In October of 2004, ACRI, AAPC

and Adalah (14) petitioned the High Court of Justice,(15) arguing that cancellation of

the tender was the ILA's way of avoiding an in-depth discussion of discrimination in

land allocation on the basis of nationality. Thus, the petition was not about a specific

tender, but about land allocation in general.

The JNF's statement of defense, presented in court on December 2004, argued that

Israel is bound by liberal-democratic principles of justice, and that all its citizens are to

be treated equally. However, it argued, since the JNF is a private organization that

owns 14% of Israel's total land, and since it is dedicated to the Zionist project of

settling Jews in Israel, the JNF has the right to decide who leases the land, even if

such a policy is incompatible with the principle of equality. Moreover, it was argued,

by allocating land to Jews, the JNF maintains its role in protecting and continuing

Jewish communal life, similar to the manner of land allocation for communal and

religious purposes made by the Waqf.(16) Such claims are awkward because, first,

(10) The

plan was initiated by the governmental company ArimöUrban Development Co Ltd.

public tender number ZF/59/2004.

(12) ILA's public tender number ZF/198/2004.

(13) Administrative Petition 2282/04.

(14) A human rights organization working to achieve equal rights for the Arab minority in Israel.

(15) HCJ 9010/04; HCJ 7452/04.

(16) The Waqf is responsible for Muslim religious endowment and typically designates buildings

or plots of land for religious or charitable purposes. The Waqf does not allocate land for housing.

Its income mostly supports the upkeep of mosques (Dumper, 1994).

(11) ILA's

�1124

E Tzfadia

discrimination on ethnic or national grounds is illegal in both the public and private

domains. Second, the JNF is not a private body. Contrary to the Waqf in Israel, the

JNF has a special status firmly grounded in Israeli law, and its land is administrated

by the state through the ILA.

Following the petition, Attorney General Menachem Mazuz recommended that all

ILA-administered land, including JNF-owned land, be marketed to all citizens, including Israeli Arabs. Seemingly, the attorney general adopted liberal-democratic ideals;

however, Mazuz also recommended that in cases where a non-Jewish citizen won the

tender for JNF-owned land the ILA would record the land as if it were state owned

and assign alternative land to the JNF. Mazuz's recommendation, which has yet to be

validated by the High Court, bridges the liberal-democratic and ethnonational logics:

``to uphold the principle of equality without harming the aims of the JNF as set down

in its mandate to settle Jews on the land it owns'' (Ministry of Justice, 2005).

The attorney general's decision followed a meeting of the heads of the JNF, ILA,

ILC, Ministry of Finance, and the State Attorney on 22 September, 2004. The rationale

behind the meeting was the concern that the High Court might reject the tender's

cancellation and instigate a public debate on JNF's land allocation policy. Jewish

communal rights and spatial Judaization were at the core of the meeting's debate.

Jacob Efrati, Director General of the ILA, argued that ``a solution for these kinds

of [communal] settlements should be found in order to preserve their [Jewish] character.

If the JNF's land cannot contribute to the Jewish character, than it shall be the structure

of the settlement-admissions committees [sic]''.(17)

Efrati's proposal to employ admissions committees in order to preserve Jewish

character warrants clarification. Admissions committees are legally based on ILC

decision 443 from 1989, which approved the authority of committees to select candidates for suburban and rural settlements, based on the candidates' suitability for

communal lifestyle as well as their approval by an external psychological diagnostic

session. The pseudo-multicultural rationale behind the admissions committees is the

concern of losing the settlement's communal spirit.(18) According to the ILC decision,

committee representatives would be appointed from among `founders' of the settlement, regional authorities, and the Jewish Agency.(19) The committee would operate

until the settlement reaches a quota of 150 families, thus ensuring that ``in the settlement there will be only settlers who have been approved by the Jewish Agency as

suitable for settling and who fulfill the obligations of the Jewish Agency'' (State

Comptroller, 2001, page 759). This means that non-Jews could not succeed in passing

the admissions process. Following the Carmiel affair, the ILC authorized the admissions committees to operate in settlements of up to 500 families (ILC decision 1015).

In other words, only after the minimum quota of 500 Jewish families was met

could Arabs take part in the free market and buy a lot in these new settlements.

Efrati's proposal is based on the idea that a settlement inhabited by 500 Jewish families

cannot be de-Judaized, corresponding with ethnonational logic. Efrati's proposal was

approved in the meeting.

The attorney general's decision can be judged in a new light: it did not put an end to

ethnonationalismöthat is, the Judaization processes and territorial accumulationönor

did it advance principles of liberal democracy. It did, however, create a new rationalization for biased land allocation, which is seemingly based on the logic of multiculturalism.

(17) ILA

protocol, 897, which was not published.

claim is presented also in academic journals (see Lehavi, 2005).

(19) The Jewish Agency is a global partnership of Jewish communities who support the immigration

and settlement of Jews in Israel.

(18) This

�Abusing multiculturalism: the politics of land allocation in Israel

1125

Shachar neighborhood in Bet Shemesh

The town of Bet Shemesh was established in the 1950s near the border with Jordan,

and was settled by poor Jewish immigrants. The occupation of the West Bank in 1967

pushed the Jordanian border further from Bet Shemesh. In the mid-1990s the Ministry

of Housing planned a new neighborhood for the town, one that would include 2300

housing units. In July of 2000 the ILA issued a public tender for marketing 100 lots for

self-construction single housing in the neighborhood.(20) The deadline for submitting

proposals was September 2000. On 26 September, the ILA published the names

of 72 families who had won the tender and asked them to come to the Ministry of

Housing's offices by 29 September in order to sign purchasing contracts. A press

release by the Ministry of Housing, which aimed to dissolve local rumors that the

new neighborhood would serve ultra-orthodox Jews, asserted on 27 September that

``an attempt by Haredim [ultra-orthodox Jews] to occupy the Shachar neighborhood

failed. The Ministry of Housing has targeted the neighborhood for secular Jews.''

When the winners arrived on 29 September to sign the contracts, it became apparent

that all of them belonged to the Haredi community. On 15 November, the ILA and

the Ministry of Housing froze the tender on the grounds that ``marketing difficulties

are expected, based on the professional analysis of the Ministry of Housing''.(21)

The 72 ultra-orthodox families who had won the tender petitioned the District

Court,(22) demanding to examine the legality of freezing the tender, arguing that

the ground for the freezing was discrimination against the Haredi community. The

Ministry of Housing's statement of defense gave the following three explanations

behind the freezing: (a) the arrival of Haredim might prevent others from moving to

the new neighborhood; (b) the neighborhood had been targeted for `general' residents

(implying that Haredim are not part of the `general' population in Israel. Indeed, in the

press release mentioned above `general population' referred to secular Jews); and (c) as

a Haredi neighborhood already exists in Bet Shemesh, Haredim have no reason to live

in other neighborhoods. Therefore, it was argued, this was a case of `equal separation'.

The court rejected the Ministry of Housing's argument and accepted the Haredim's

petition, thereby cancelling the freezing of the tender. The court even adopted a

multicultural discourse protecting communal rights of minorities through land allocation:

``Obviously, this project should be open to everyone, and it is impossible to

prevent someone from living there based on his religion. The `equal separation'

argument cannot be voiced by the majority that requests to block the right of

the other community... . However, when the argument for separation is voiced by the

[minority] community that wishes to preserve its culture and to protect it from

strangers, it seems that `color blindness' should back down because of the damage

that might be caused to the unique community.''(23)

The Bet Shemesh case explores another dimension of abusing multicultural

discourse, this time by a government authority. The motivation behind it is different

from that in the Carmiel case: in Carmiel, the multicultural discourse served an

ethnonational project, while in Bet Shemesh it served a neoliberal project, in which

the Ministry of Housing adopted a business-oriented role and attempted to market the

lots in the new neighborhood as if it were a private business. Nevertheless, in both

cases the beneficiary of multicultural discourse is the majority group.

(20) ILA's

public tender number YM/2000/145.

1 of petition 209/01: Fintz vs the Minister of Housing.

(22) Jerusalem district court, 209/01: Fintz vs the Minister of Housing.

(23) Judge Judith Tzur, Jerusalem district court decision 209/01, article 58, 14 November, 2004.

(21) Appendix

�1126

E Tzfadia

New suburbs and student villages in the Negev

``There is a lot of talk about the dangerous transformation in the Negev's demographic balance between the Jewish and Arab settlement. In my opinion this is not

the real problem, because demographic balance can easily be changed: it is possible

to build a big [Jewish] city and immediately there will be a revolution in the

demographic balance for our own good. But, a positive demographic balance

does not assign control over space. In order to control the space it is necessary

to settle in many places.''

Sharon (2000, page 14)

The words of Ariel Sharon, several months before he was elected prime minister,

represent the centrality of ethnonational discourse in establishing new Jewish communal

settlements in the Negev Desert. On 14 July, 2002, Sharon's government declared that

Jewish settlement in Israel is a fulfillment of the Zionist vision, and essential to the

security of the state. The State Comptroller enumerated 150 initiatives for establishing

new Jewish settlements during 1997 ^ 2002 (not including in the occupied territories),

many of them in the Negev (State Comptroller, 2005). However, the planning authorities,

human rights groups, and environmental organizations all argue that the trend of new

settlements contradicts the current planning approach (as was detailed above), causes

environmental damage, and increases social inequality at a time when tens of thousands

of Palestinian Bedouins live in unrecognized settlements in the Negev, and dozens of

Jewish towns are crying out for new residents (State Comptroller, 2005). Therefore,

many projects have faced difficulties, and some of them have been cancelled. This should

be regarded as another challenge to ethnonationalism in Israel.

Politicians, civil servants, and Jewish organizations that promote the continuation

of Jewish settlement support NGOs that are known for their activism in the field of

settlement. Two such groups are Or National Missions (`Or' means `light'), which

advances communal suburbs, and Ayalim (`Deer'), which advances student villages.

Both are active in the Negev.(24) Or National Missions designates new settlements for

specific populations: suburbs for secular Jews, religious Jews, police personnel and

their families, employees of the security services, and wealthy American Jews. It also

promotes ecological villages for environmentalists. None of the suburbs are designated

for minorities, certainly not for Arabs. Ayalim calls upon students to ``Live among

people like you.'' The two NGOs operate admissions committees that are guided by the

principle of `communal suitability'. This principle is supported by the residents as well.

Azriel Levy, one of the initiators of a new suburb near Yeruham, a relatively poor

Jewish town in the Negev, claimed:

``We don't want it to be another neighborhood named `Yeruham B', and we do have

an interest in separating the education systems. Not because we are against partnership with Yeruham, but because we want something that suits the people that want

to live in the settlement'' (quoted in Rinat, 2002).

However, these NGOs' communal intentions and discourse of recognition conceal

their support for ethnonationalism. Both attribute ethnonational territorial value to

the settlement venture. Or National Missions regards itself as a branch of Gush

Emunim, an organization that advances colonization of the West Bank (Newman,

2005). The leaders of Or National Missions justify settlement as an answer to the

demographical and territorial threat posed by Palestinian Bedouins in the Negev.

Thus, they argue, ``settlement is the most important national mission ... it is necessary

to bring 20,000 Jews to the Negev every year'' (quoted in Abramson, 2004).

(24) All

new settlements in the Negev since 2000 have been established by `Or' and `Ayalim'. `Or' has

already established three new settlements in the Negev, and 15 others are planned. `Ayalim'

has established two new settlements in the Negev.

�Abusing multiculturalism: the politics of land allocation in Israel

1127

Ayalim makes residence in the student villages conditional upon military service,

which is conducted mainly by Israeli Jews. Among the 250 students living in the

village, only one is not Jewish. Ayalim links itself to Zionism's pioneer past. Its

Internet site states that ``Ayalim Association believes that bringing students to settle

in the Negev and the Galilee is a national undertaking of supreme importance'' and

that ``The village offers its young residents opportunities to experience a lifestyle that

is rich with Zionist content.'' (25) In an interview with a daily newspaper, one of the

founders voiced a lucid ethnonational position: ``Unless the population in the Negev

grows, Israel will be in danger. The state is headed toward territorial compromise,

so in places that we know belong to us we must settle. We are definitely a Zionist

settlement movement. The motivation of the project is to bring Jews to the Negev

and Galilee'' (quoted in Traubman, 2005).

The NGOs' dual toneö both communal and ethnonational ö enables politicians

to support their activism in the field of settlement. These two groups enjoy land

allocation for new settlements and public financing. They have representatives

in administration meetings that deal with planning for the Negev, and their contribution to the ethnonational project is emphasized by Zionist organizations and politicians.

At the initiation ceremony for a new student village, Prime Minister Sharon addressed

the link between Zionist pioneers and the students: ``You, members of Ayalim, revive

here not only the land of the Negev, but also the pioneer spirit of Ben-Gurion and the

first pioneers. Many of them were students like you, who immigrated to Israel in order

to reestablish by their own hands the link between the Jewish people and its land.''

This activism, Sharon said, carries material benefits as well: ``You have an initiative,

you have an idea, an exceptional idea by the way. Push it ahead and you will get help,

both from donors and from the government'' (Prime Ministry Office, 2004).

Conclusion: misusing or abusing multiculturalism?

The three cases presented above suggest a new direction in the politics of land

allocation that seeks to link the multicultural protection of communality with the

traditional cultural and material injustice of ethnonationalism. It endeavors to

change the political discourse and to impart legitimacy to inequality and hierarchical

social relations in the name of protecting communal rights. Nevertheless, the paper

does not aim to undermine the moral grounds of multiculturalism, but rather to

explore a sociopolitical dynamic and the results of importing multiculturalism

to societies with a strong ethnonational background. Specifically, the cases focused

on the use of multicultural discourse. In contrast to the ideal that minorities can

employ this discourse in order to present claims for recognition and allocation, in the

Israeli case, this discourse serves the interests of the group of secular European Jews

that has enjoyed generous land allocation in the past and now seeks new alternatives

to justify continued biased allocation. This process can be understood as a dialectic of

the Israeli regime, in which the contradiction between ethnonationalism and liberalism

is reconciled by a fusion of `cosmetic' multiculturalism. But `cosmetic' multiculturalism,

as a general policy that advances recognition, is not a promising way to achieve fair

allocation.

The multiple interpretations of multiculturalism range from the liberal to the

radical. While the liberal version facilitates recognition, the radical version regards

multiculturalism as a political doctrine that aims to solve historical injustice of cultural

and material types (Shohat and Stam, 2003; Young, 2005). The variety of interpretations of multiculturalism is one source of the abuse of multiculturalism. This kind of

(25) Ayalim,

``For settlement'' (http://www.ayalim.org.il/index.php?page id=92).

�1128

E Tzfadia

abuse characterizes dominant groups as well as politicians and administrators who

support the ethnonational logic and, subsequently, biased allocation. Yet, while

`misuse' indicates wrong use, the moral legitimacy of multiculturalism, the delegitimization of ethnonationalism, and the fact that multiculturalism has allocational

implications enable the abuse of multiculturalism ö that is, improper and unjust

utilization of multiculturalism in order to benefit privileged sectors.

It is fitting to conclude this paper with a quotation from the protocol of

the 14 June 2005 meeting of the Constitution, Law and Justice Committee of the

Israeli Parliament, in its discussion on future land legislation for a `consensual

constitution', the same meeting cited at the beginning of this paper. The words of

Daniel Polisar, an expert invited to the meeting, explore the meaning behind abusing

multiculturalism:

``The solution is simple. The role of the Knesset [Israeli Parliament] is to set the

principles upon which the State's existence is to be based. And one of these principles is that there must be Jewish settlement here, either directly or through distinct

communities'' (Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee, 2005, emphasis added).

Acknowledgements. My thanks go to Daniel De-Malach, Pnina Mutzafi-Haller, and Adrian Guelke,

who organized the meetings, and to Yishai Blank and Tovi Fenster for their useful comments.

References

Abramson A, 2004, ``The new Zionism'' Negev Time 2 April (in Hebrew)

Agius P, Jenkin T, Jarvis S, Howitt R, Williams R, 2007, ``(Re)asserting indigenous rights and

jurisdictions within a politics of place: transformative nature of native title negotiations in

South Australia'' Geographical Research 45 194 ^ 202

Al-Haj M, 2002,``Multiculturalism in deeply divided societies: the Israeli case'' International Journal

of Intercultural Relations 26 169 ^ 183

Anderson K, 1991 Vancouver's Chinatown: Racial Discourse in Canada, 1874 ^ 1980 (McGill-Queens

University Press, Montreal)

Anderson K, 1998, ``Sites of difference: beyond a cultural politics of race polarity'', in Cities of

Difference Eds R Fincher, J M Jacobs (Guilford Press, New York) pp 201 ^ 225

Anderson K, 2000, ``Thinking `postnationality': dialogue across multicultural, indigenous, and

settler spaces'' Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90 381 ^ 391

Banting K G, 2005, ``The multicultural welfare state: international experience and North American

narratives'' Social Policy and Administration 39(2) 98 ^ 115

Banting K G, Kymlicka W, 2004, ``Do multiculturalism policies erode the welfare state?'', in

Cultural Diversity versus Economic Solidarity (Proceedings of the Seventh Francqui Colloquium)

Ed. P Van Parijs (De Boeck, Brussels) pp 227 ^ 284

Barry B, 2002 Culture and Equality: An Egalitarian Critique of Multiculturalism (Harvard University

Press, Cambridge, MA)

Benvenisti E, 1998, ``Separate but equal in allocating state land for housing'' Iyunei Mishpat

(Tel-Aviv University Law Review) 21 769 ^ 798 (in Hebrew)

Central Bureau of Statistics, 2003 Local Authorities in Israel (State of Israel, Jerusalem)

Colin H S, 1993, ``Customs, traditions, and the politics of culture: aboriginal self-government

in Canada'', in Anthropology, Public Policy, and Native Peoples in Canada Eds N Dyck,

J B Waldram (McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal) pp 311 ^ 333

Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee, 2005, ``Consensual Constitution: Land and Settlement'',

Protocol No. 501 (in Hebrew)

Dumper M, 1994 Islam and Israel: Muslim and Religious Endowments and the Jewish State

(Institute for Palestine Studies, Washington, DC)

Fincher R, Jacobs J M (Eds), 1998 Cities of Difference (Guilford Press, New York) pp 1 ^ 25

Forman G, Kedar A, 2004, ``From Arab land to `Israel lands': the legal dispossession of the

Palestinians displaced by Israel in the wake of 1948'' Environment and Planning D: Society

and Space 22 809 ^ 830

Fraser N, 2003, ``Social justice in the age of identity politics: redistribution, recognition,

and participation'', in Redistribution or Recognition? A Political ^ Philosophical Exchange

Eds N Fraser, A Honnet (Verso, London) pp 7 ^ 109

�Abusing multiculturalism: the politics of land allocation in Israel

1129

Gavison R, 2003, ``Constitutions and political reconstruction? Israel's quest for a constitution''

International Sociology 18(1) 53 ^ 70

Gavison R, Greidi-Schwartz E, 2005,``Guidelines for discussion on the issue of land and settlement:

background material for June 14, 2005 Meeting of Constitution, Law and Justice Committee'',

Israeli Parliament, Jerusalem (in Hebrew), http://www.huka.gov.il/wiki/material/data/H02-102005 8-56-01 hityashvut.doc

Harris C, 2004, ``How did colonialism dispossess? Comments from an edge of empire'' Annals of

the Association of American Geographers 94 165 ^ 182

Imbroscio D L, 2004, ``Can we grant a right to place?'' Politics and Society 32 575 ^ 609

Jabareen H, 2000, ``Israeliness that predicts the future of the Arabs according to Jewish-Zionist

time, in space that lacked Palestinian time'' Law and Regime 6 53 ^ 72 (in Hebrew)

Jameson F, 1984, ``Postmodernism, or the cultural logic of late capitalism'' New Left Review

number 146, 53 ^ 92

Kedar A, 2000, ``First step in a difficult and sensitive road: preliminary observations on Qaadan

v Ketzir'' Israel Studies Bulletin 16 4 ^ 11

Khamaissi R, 2003, ``Mechanism of land control and territorial Judaization in Israel'', in

In the Name of Security: Studies in Peace and War in Israel in Changing Times Eds M Al-Haj,

U Ben-Eliezer (University of Haifa Press, Haifa) pp 421 ^ 448 (in Hebrew)

Khoury J, 2004a, ``New neighborhood in Carmiel for Jews only'' Haaretz 30 July (in Hebrew)

Khoury J, 2004b, ``ILA's `Jews only' land sales challenged'' Haaretz 12 October (in Hebrew)

Kimmerling B, 2001 The Invention and Decline of Israeliness: State, Society, and the Military

(University of California Press, Berkeley, CA)

Lehavi A, 2005, ``New residential communities in Israel: between privatization and separation''

Din-u-Devarim: Haifa Law Review 2 63 ^ 140 (in Hebrew)

Ministry of Justice, 2005, ``Press release'', 27 January (in Hebrew)

Moran A, 2002, ``As Australia decolonizes: indigenizing settler nationalism and the challenges

of settler/indigenous relations'' Ethnic and Racial Studies 25 1013 ^ 1042

Murphy A B, 2002, ``National claims to territory in the modern state system: geographical

considerations'' Geopolitics 7 193 ^ 214

Newman D, 2005, ``From `Hitnachalut' to `Hitnatkut': the impact of Gush Emunim, and the

Settlement Movement on Israeli society'' Israel Studies 10(3) 192 ^ 224

Penrose J, 2002, ``Nations, states and homelands: territory and territoriality in nationalist thought''

Nations and Nationalism 8 277 ^ 297

Prime Ministry Office, 2004, ``Speech of Prime Minister in Adiel, November 21, 2004'', Archive of

Speeches, http://www.pmo.gov.il/PMO/Archive/Speeches/2004/11/speech22111.htm (in Hebrew)

Qadeer M A, 2003, ``Ethnic segregation in a multicultural city: the case of Toronto, Canada'',

WP 28, CERIS, Toronto

Qadeer M A, 2005, ``Ethnic segregation in a multicultural city'', in Desegregating the City: Ghettos,

Enclaves, and Inequality Ed. P D Varady (SUNY Press, Albany, NY) pp 49 ^ 61

Ram U, 2004, ``The state of the nation: contemporary challenges to Zionism in Israel'', in Israelis

in Conflict: Hegemonies, Identities and Challenges Eds A Kemp, D Newman, U Ram,

O Yiftachel (Sussex Academic Press, Brighton, Sussex) pp 305 ^ 320

Reitman M, 2006, ``Uncovering the white place: whitewashing at work'' Social and Cultural

Geography 7 267 ^ 282

Rinat Z, 2002, ``A settlement for policemen'' Ha'aretz 23 August (in Hebrew)

Sandercock L, 2000, ``When strangers become neighbours: managing cities of difference'' Planning

Theory and Practice 1(1) 13 ^ 30

Shachar A, 1998, ``Reshaping the map of Israel: a new national planning doctrine'' Annals of the

American Academy of Political and Social Science 555 209 ^ 218

Shafir G, Peled Y, 1998, ``Citizenship and stratification in an ethnic democracy'' Ethnic and Racial

Studies 21 408 ^ 427

Shafir G, Peled Y, 2002 Being Israeli: The Dynamics of Multiple Citizenship (Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge)

Shamir R, Ziv N, 2001, ``State-oriented and community-oriented lawyering for a cause: a tale of

two strategies'', in Cause Lawyering and the State in a Global Era Eds A Sarat, S Scheingold

(Oxford University Press, New York) pp 287 ^ 304

Sharon A, 2000, ``Land as an economic device to mold infrastructure and to reduce social

inequalities'' Land 50 10 ^ 21 (in Hebrew)

�1130

E Tzfadia

Shetreet S, 2003, ``On the issue of equality of separate residence in rural and communal settlements:

was the ruling in the Quadan case unavoidable?'' Land: Periodical on Land Issues 56 27 ^ 65

(in Hebrew)

Shohat E, Stam R (Eds), 2003 Multiculturalism, Postcoloniality, and Transnational Media (Rutgers

University Press, New Brunswick, NJ)

State Comptroller, 2001 Annual Report 51b (State of Israel, Jerusalem) (in Hebrew)

State Comptroller, 2005 Annual Report 55b (State of Israel, Jerusalem) (in Hebrew)

Storey D, 2001 Territory: The Claiming of Space (Prentice-Hall, Harlow, Essex)

Traubman T, 2005, ``8 students fund-raised 38 millions shekels'' Ha'aretz 30 August (in Hebrew)

Tully J, 2000, ``Struggles over recognition and distribution'' Constellations 7 469 ^ 482

Tzfadia E, Yacobi H, 2007, ``Multiculturalism, nationalism and urban politics: the case of Ashdod''

Israeli Sociology 9(1) 127 ^ 148 (in Hebrew)

Van Kempen R, Ozuekren A S, 1998, ``Ethnic segregation in cities: new forms and explanations

in a dynamic world'' Urban Studies 35 1631 ^ 1656

Wilensky H L, 1975 The Welfare State and Equality: Structural and Ideological Roots of Public

Expenditure (University of California Press, Berkeley, CA)

Yiftachel O, 2006 Ethnocracy: Land and Identity Politics in Israel/Palestine (Penn State University

Press, University Park, PA)

Yiftachel O, Yacobi H, 2003, ``Urban ethnocracy: ethnicization and the production of space in

an Israeli `mixed city' '' Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 21 673 ^ 693

Yonah Y, 2005, ``Toward multiculturalism in Israel: spatial aspects'', in Memory and Meaning:

The Architectural Construction of Place Eds R Kallus, T Hatuka (Resling, Tel Aviv)

pp 137 ^ 176 (in Hebrew)

Young M I, 2005, ``Self-determination as non-domination: ideals applied to Palestine/Israel''

Ethnicities 5 139 ^ 159

Yuval-Davis N, 1997, ``Ethnicity, gender relations and multiculturalism'', in Debating Cultural

Hybridity: Hybridity, Multi-cultural Identities, and the Politics of Anti-racism Eds P Webner,

T Modood (Zed Books, London) pp 193 ^ 208

ß 2008 Pion Ltd and its Licensors

�Conditions of use. This article may be downloaded from the E&P website for personal research

by members of subscribing organisations. This PDF may not be placed on any website (or other

online distribution system) without permission of the publisher.

�

Erez Tzfadia

Erez Tzfadia