Chapter VII. The Scientific View of The World

Chapter VII. The Scientific View of The World

Uploaded by

markgranCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter VII. The Scientific View of The World

Chapter VII. The Scientific View of The World

Uploaded by

markgranOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Chapter VII. The Scientific View of The World

Chapter VII. The Scientific View of The World

Uploaded by

markgranCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter VII.

The Scientific View of the World

pp. 287 - 313

Introduction: “The Seventeenth Century has been called the century of genius.” Between the birth of Galileo and the

death of Newton, science became “modern.” When Galileo was young, scientists were alone and the proper

methodology was not clear; by the death of Newton (1727) scientists were a community, science had prestige,

methods of inquiry had been defined, the store of knowledge had been vastly increased, the first modern coherent

theory of the physical universe had been presented, scientific knowledge was applied to practical fields, science was

accepted as basic to progress, and science was “popularized,” accepted by non-scientists. The impact was wide-

spread, affecting thinking about religion (the nature of the relationship between God and man), and leading to the view

that the universe was an orderly, rational place where ideas could change man--thus the foundations of belief in free,

democratic institutions.

32. Prophets of a Scientific Civilization: Bacon and Descartes pp. 287 - 292

A. Science before the Seventeenth Century

1. Leonardo: universal genius but isolated, ideas not transmitted

2. Skepticism: belief no certain knowledge could be reached: Montaigne

3. Tendency to over-belief

a. Lack of dividing lines between chemistry/alchemy, astronomy/astrology

b. Charlatans: Nostradamus and Paracelsus; belief in witches

B. Bacon and Descartes

1. Both doubted non-religious beliefs of preceding generations. They ridiculed faith in ancient texts.

Medieval Scholastic philosophers had embraced Aristotle so enthusiastically that they neglected to subject

his ideas to tests. Likewise, they rejected the deductive, rationalistic, logic of the Scholastics (which

proceeded from definitions and general propositions to deduce logically). Deductive logic was replaced

by inductive reasoning, in which truth is revealed by experimental testing and investigations of

hypotheses.

2. Francis Bacon (1561-1626)

a. Bacon wrote Novum Organum, in which he insisted on inductive reasoning, from the concrete,

particular to the abstract, general; rejected traditional ideas and preconceptions; and favored

empiricism, with knowledge to be derived from observation and experience. He also wrote New

Atlantis, portraying a scientific utopia where there was no break between pure science and

technological invention

b. Bacon had no influence on actual science; he lacked knowledge of the new work being done in his

time; and he failed to understand the role of mathematics, which involves deductive logic rather than

empiricism.

3. René Descartes (1596-1650)

Descartes was primarily a mathematician, founder of co-ordinate geometry; believed nature could be

reduced to mathematical form. He wrote Discourse on Method in which he advanced the principle of

systematic doubt. Cogito ergo sum was the basis for his logical proof of God. From this came his

Cartesian dualism, a system of two realities: subjective experience, mind and spirit and extended

substance, all outside the mind and thus objective--occupying space and thus quantifiable, reducible to

formulae and equations. But he agreed with Bacon that science should lead to a practical philosophy to

enable mankind to become “the masters and possessors of nature.

33. The Road to Newton: The Law of Universal Gravitation pp. 293 - 300

A. Scientific Advances:

1. With the increased trade and travel of the Age of Exploration, botany boomed, often for purely utilitarian

motives.

2. An intensive, open-minded observation of anatomy began by 1500. Vesalius ’ De Fabrica (On the

Structure of the Human Body) (1543) replaced reliance on the often inaccurate work of the Hellenistic

scientist Galen (2d century AD). The work of English physician William Harvey, described in On the

Movement of the Heart and Blood (1628), established the notion of blood circulation. Using the new

1 Palmer Chapter 7 The Scientific View of the World

microscope, Malpighi identified capillaries in 1661, and Leeuenhoek observed and recorded blood

corpuscles, spermatozoa, and bacteria.

3. Mathematics developed rapidly with the spread of Arabic numerals, the introduction of decimals and

algebraic symbols, and finally the development of logarithms by Napier in 1614. Descartes’ coordinate

geometry, Pascal’s theory of probability, and the invention of calculus by Newton and Leibniz were of

immense importance to science in general and astronomy and physics in particular.

B. The Scientific Revolution: Copernicus to Galileo

1. According to Ptolemy, a Hellenistic Greek of 2d century AD Alexandria, the universe was earth-

centered, with a cosmos of solid earth, crystalline spheres, fixed stars, and the empyrean, home of angels.

All beings were ranked in a hierarchy of ascending perfection. The theory clearly fit theologically, but it

was also believable scientifically. It was formulated in precise, mathematical terms, and though

exceedingly complicated, it worked.

2. Copernicus (d. 1543), On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Orbs (1543)

Copernicus based his ideas on the new theory that numbers were the key to nature and that simplicity

was the sign of truth. His observations showed that another Hellenistic idea was to be preferred to the

Ptolemaic: A sun-centered universe with revolving planets and an earth rotating on its axis. Yet while

the theory was simpler, it provided too drastic a shift to be acceptable in an age of theological controversy

(Reformation). Besides, the greatest expert of the day, Tycho Brahe , observed significant flaws.

Round One to Ptolemy.

3. Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) managed to clean up Copernican errors by showing that planets moved in

elliptical orbits. His revised theory was simple, had clear proof in mathematics, and it could be tested by

observations. The “real world” did correspond to the purely rational world of mathematical harmony.

4. Galileo (1564-1642): provided further proof of Copernicus through observations begun using his new

telescope in 1609--the moon had craters, the sun had spots, Jupiter had moons clearly rotating, and the

stars were clearly much further away than had been thought. Galileo also suggested the uniformity of

matter in the universe. He proceeded to develop mathematical laws of motion on earth--falling bodies,

dynamics/inertia. These ideas shattered notions based on Aristotelian logic and long accepted by the

Church as the truth. And Galileo, fiery and stubborn, was not the one to remain quiet about his findings.

Though many leading churchmen quietly agreed with Galileo, Mother Church condemned the new heresy

and banned Galileo’s book, Dialogue on Two World Systems. When Galileo refused to keep quiet, the

Church tried and convicted him, holding him under house arrest until his death. But the book was

published, in Protestant Holland.

C. The Achievement of Newton: The Promise of Science

l. Newton (1642-1727) brought Kepler and Galileo together by proving why planets tend to fall to the sun

and thus moved in elliptical orbits. He showed that gravity was a form of universal gravitation. In his

Principia Mathematica: The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (1687) he showed that

all motion could be described in the same formulae: moving as if every particle attracted every other

particle with a force proportion to the product of the two masses, and inversely proportional to the

distance between them. The theory required calculus, new measurements of the earth’s size, and

experiments with the pendulum.

2. Newton’s work led to chronometers and the ability to precisely determine longitude; map-making

(cartography) became a science. Math (and better metallurgy) produced much better artillery (aimed

more precisely with the aid of calculus). Artillery meant warfare was more expensive--with advantages

to larger nations with more efficient central governments. Improve firearms also gave Europeans a

major advantage over non-Europeans. Steam power also resulted from improvements in science:

Scientists, mechanics, and instrument makers combined to produce the steam engine--with a practical

non-scientist, Thomas Newcomen finally putting all the pieces together (and getting all the credit, not to

mention the cash).

D. The Scientific Revolution and the World of Thought Man was no longer the center of creation; the sky itself

was shown to be an illusion. Science made clear a universe of terrifying size and silence. Yet it also

produced a confidence in the power of the mind to discover universal laws--and contributed to the

secularization of society. Religion was to decline, with science reassuring man that his universe was

reasonable, orderly, and rational. Man could aspire to make human society equally orderly and rational.

2 Palmer Chapter 7 The Scientific View of the World

34. New Knowledge of Man and Society pp. 300 - 307

A. The Current of Skepticism

The inter-relationship of Europe and the world brought new medicines and new diseases, plus new wealth,

new foods, new products. Knowledge of the variety of human types and human customs and cultures tended

to undermine old thought. As philosophers (or social scientists) viewed human diversity, they gained a sense

of the relative nature of social institutions. It became much harder to believe in absolute values, that one set

of human values or institutions was more likely to be God-given than another. Jesuit missionaries, the most

traveled of educated men, stressed natural goodness and alertness of the peoples they contacted. Others

came to praise non-Christian religions for their virtues. Perhaps the most important Skeptic was Pierre

Bayle (1647-1706); his Historical and Critical Dictionary showed the gullibility of people and the problem

of distinguishing truth from opinion and stressed religious toleration. “For Bayle, as for Montaigne, no opinion

was worth burning your neighbor for.”

B. New Sense of Evidence

l. In English law, new rules of evidence were put into use, with less discretion by judges. For example,

hearsay evidence was not allowed, and accused were allowed legal counsel. Confessions could not be

extracted by torture--and there was a new search into the validity of confessions in general. But torture

continued to be used in Europe.

2. Historians began to insist on evidence and turned to greater use of archival sources. The science of

authenticating coins, manuscripts, etc. was begun. Others began to rethink the age of the world. James

Usher, Anglican bishop of Ireland, declared the Creation dated to 4004 BC (a date still used by some

fundamentalists). A scholar announced the earth was 170,000 years old, a figure seen as fantastic and

appalling.

3. Catholics adopted the Gregorian calendar (Gregory XIII) in the 1500s, though Protestants continued to use

the Julian. The English adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1752, but the Russians did not until 1918. (in

both cases: Why?)

C. Scholars worked in Biblical criticism, applying basic ideas of textual criticism to the New Testament. Other

critics began denying miracles because of their faith in the regularity of nature and faulty human credulity.

1. Baruch de Spinoza (1632-1677) was most upsetting to the faithful. He was a scientific humanist who

stated that God and the World are not separate. He rejected revelation and all revealed religion; he

believed one should live his life based on a stern, pure ethical code. Scarcely read because of his

“impiety,” his ideas spread slowly.

2. John Locke (1632-1704) was more reassuring, and thus more widely read. He favored an established

church, but called for toleration for all but Catholics (seen as adherents of a foreign power) and atheists

(lacking a basis of moral responsibility). His Essay Concerning the Human Understanding (1690)

stated that all knowledge is derived from sensate experience, since the mind at birth is a tabula rasa.

He believed the environment was all-important; all crime, false ideas, and superstitions came from bad

environment, (including bad education and bad social institutions). His ideas became the basis of

confidence in the possibility of social progress, with government playing the key role.

3 5. Political Theory: The School of Natural Law pp. 307 - 313

A. Political theory is practical, for it deals with what IS rather than what OUGHT to be. Machiavelli began by

ignoring the Scholastic notion of what is the “best” form of government to examine how rulers actually

behaved. He noted that they worked on one principle: what advanced their power, without concern for

morality. The seventeenth century returned to the classical notion of natural law.

B. Natural Law “held that there is, somehow, in the structure of the world, a law that distinguishes right from

wrong....[and] that right is ‘natural,’ not a mere human invention. This right is not determined, for any

country, by its heritage, tradition, or customs....All these may be unfair or unjust. No king can make right that

which is wrong. No people, by its will as a people, can make just that which is unjust. Right and law, in the

ultimate sense, exist outside and above all peoples.” Man is rational and can discover natural--or universal--

law by his reason. Attempts were made to create international law based on natural law (Grotius and

Pufendorf), but in the long run, little has emerged. Ironically, both absolutism and constitutionalism have been

justified by reference to natural law.

3 Palmer Chapter 7 The Scientific View of the World

C. Thomas Hobbe s (1588-1679): Disliked the disorder and viole nce of civil war. He concluded that man “in a

state of nature” lacked even the rudimentary ability for self-rule; that he was quarrelsome, vicious, and

brutal, and his life was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Out of fear, men made a contract: a ruler

was given absolute power to enable a maintenance of order. Absolutism was to produce civil peace,

individual security, and the rule of law. Absolute power was an expedient to promote the individual welfare--

not as a means to a totalitarian state. (Leviathan)

D. John Locke (1632-1704) agreed that government was a contract, but man was inherently good, only

hindered by lack of public authority. Man had inalienable rights--life, liberty, and property. By his own power

he could not protect his rights, so he set up a government to enforce the rights of all. The contract has mutual

obligations; if the ruler violates them, he people have the right of rebellion. Locke took a specifically English

event (the Glorious Revolution) and gave it universal meaning, influencing many later thinkers. He carried

over ideas that were basically medieval, but in a specifically secular way. (Two Treatises on Government)

4 Palmer Chapter 7 The Scientific View of the World

You might also like

- Copernicus and Kepler: A New View of The Universe: Geocentric TheoryDocument8 pagesCopernicus and Kepler: A New View of The Universe: Geocentric Theoryapi-287069252No ratings yet

- Intellectual Revolutions That Defined SocietyDocument20 pagesIntellectual Revolutions That Defined SocietydasalchinNo ratings yet

- Scientific Revolution PPT Accompanying Lecture 2019 UpdatedDocument21 pagesScientific Revolution PPT Accompanying Lecture 2019 UpdatedjhbomNo ratings yet

- A Group Assignment: in A Flexible-Offline ClassesDocument28 pagesA Group Assignment: in A Flexible-Offline ClassesRecca CuraNo ratings yet

- 3 Intellectual Revolutions That Defined SocietyDocument14 pages3 Intellectual Revolutions That Defined SocietyJhomel EberoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Intellectual Revolutions That Defined SocietyDocument17 pagesChapter 2 Intellectual Revolutions That Defined SocietyRaeNo ratings yet

- STS Outline Chap.2Document6 pagesSTS Outline Chap.2kevin funtallesNo ratings yet

- Scientific Revolution AnswerDocument7 pagesScientific Revolution AnswerSandhya BossNo ratings yet

- The Scientific Revolution - OralDocument6 pagesThe Scientific Revolution - OralJosefina KeokenNo ratings yet

- STSDocument4 pagesSTSFrecy Mae BaraoNo ratings yet

- Lecture 7 The Scientific RevolutionDocument71 pagesLecture 7 The Scientific Revolutionkaijun.cheahNo ratings yet

- Science RevolutionDocument9 pagesScience RevolutionMark Jeso BadanoyNo ratings yet

- Sci Rev Inventorsw QsDocument9 pagesSci Rev Inventorsw QsLashanti FranceNo ratings yet

- AP European History-Ch16Document11 pagesAP European History-Ch16Erika LeeNo ratings yet

- The Scientific RevolutionDocument3 pagesThe Scientific Revolutionapi-508882599No ratings yet

- Cambridge 2011Document8 pagesCambridge 2011Carolina del Pilar Quintana NuñezNo ratings yet

- Science and TechnologyDocument3 pagesScience and TechnologySandara ZacariaNo ratings yet

- Scientific RevulotionDocument29 pagesScientific RevulotionJohn Paul P CachaperoNo ratings yet

- Revolutions of The Heavenly Spheres in 1543, The Same YearDocument4 pagesRevolutions of The Heavenly Spheres in 1543, The Same YearAsh HassanNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of ScienceDocument48 pagesA Brief History of ScienceHarlette A. LaguidaoNo ratings yet

- Scientific Revolution and EnlightenmentDocument3 pagesScientific Revolution and Enlightenmentpriyatiyagi14No ratings yet

- Chapter 16Document11 pagesChapter 16Taliana Roscoe SharpeNo ratings yet

- STS 1Document7 pagesSTS 1Jolie Mar ManceraNo ratings yet

- Scientific Revolution: Galileo Galilei - Italian Mathematician in University of PaduaDocument6 pagesScientific Revolution: Galileo Galilei - Italian Mathematician in University of PaduaDaniel VasquezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 New Directions in Thought OutlineDocument16 pagesChapter 6 New Directions in Thought Outlineapi-324512227100% (1)

- The Evolution of PhysicsDocument17 pagesThe Evolution of PhysicsYtle08No ratings yet

- Gec8 PointersDocument11 pagesGec8 PointersshenNo ratings yet

- Sciteso PPTDocument72 pagesSciteso PPTCharles NavarroNo ratings yet

- Module Lesson 3.5 Scientific Revolution and EnlightenmentDocument11 pagesModule Lesson 3.5 Scientific Revolution and EnlightenmentJayson DapitonNo ratings yet

- Scientific RevolutionDocument2 pagesScientific RevolutionPaula OteroNo ratings yet

- Johannes Kepler - Including a Brief History of Astronomy and the Life and Works of Johannes Kepler with Pictures and a Poem by Alfred NoyesFrom EverandJohannes Kepler - Including a Brief History of Astronomy and the Life and Works of Johannes Kepler with Pictures and a Poem by Alfred NoyesNo ratings yet

- The RenaissanceDocument15 pagesThe Renaissancetobianimashaun99No ratings yet

- The 16th Century Revolution in ScienceDocument32 pagesThe 16th Century Revolution in ScienceJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- The Scientific RevolutionDocument10 pagesThe Scientific RevolutionMegha ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Top 13 Important Thinkers in The Scientific RevolutionDocument10 pagesTop 13 Important Thinkers in The Scientific RevolutionKim Lia ENo ratings yet

- Chapter 1.3Document5 pagesChapter 1.3Wild RiftNo ratings yet

- Module 9Document4 pagesModule 9bayoterica39No ratings yet

- Brief History of ScienceDocument136 pagesBrief History of ScienceKim Lee100% (1)

- Astrology to Astronomy - The Study of the Night Sky from Ptolemy to Copernicus - With Biographies and IllustrationsFrom EverandAstrology to Astronomy - The Study of the Night Sky from Ptolemy to Copernicus - With Biographies and IllustrationsNo ratings yet

- Scientific RevolutionDocument32 pagesScientific RevolutionJannatul FerdousNo ratings yet

- The Scientific Revolution PDFDocument8 pagesThe Scientific Revolution PDFMaho ShallNo ratings yet

- Late Medieval Science: Causes 1Document6 pagesLate Medieval Science: Causes 1Anushree MahindraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 STSDocument5 pagesChapter 2 STSevangelistakatrina523No ratings yet

- LESSON 8 The LEAP of Science and Technology During The Scientific RevolutionDocument3 pagesLESSON 8 The LEAP of Science and Technology During The Scientific RevolutionBEATphNo ratings yet

- Group 3Document46 pagesGroup 3Kristel May SomeraNo ratings yet

- Discussion: Mystery Presented A Stridently Copernican Worldview Dedicated To Drawing TogetherDocument3 pagesDiscussion: Mystery Presented A Stridently Copernican Worldview Dedicated To Drawing TogetherjunjurunjunNo ratings yet

- Origin and History of PhysicsDocument7 pagesOrigin and History of PhysicsScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- AP European History Chapter 18 NotesDocument12 pagesAP European History Chapter 18 NoteslevisaadaNo ratings yet

- Intro To Philosophy Wk. 6Document11 pagesIntro To Philosophy Wk. 6Anggono WianNo ratings yet

- Sience and Reality PolanyiDocument21 pagesSience and Reality PolanyiGustavo Dias VallejoNo ratings yet

- The Scientific RevolutionDocument6 pagesThe Scientific RevolutionasiimchughtaiNo ratings yet

- Mod West Assignment 2Document5 pagesMod West Assignment 2tishaujjainwal08No ratings yet

- 1 The Enlightenment and RevolutionsDocument30 pages1 The Enlightenment and Revolutionsa01613848No ratings yet

- Practical Matter: Newton's Science in the Service of Industry and Empire, 1687–1851From EverandPractical Matter: Newton's Science in the Service of Industry and Empire, 1687–1851No ratings yet

- CH 22 Sec 1 - The Scientific RevolutionDocument6 pagesCH 22 Sec 1 - The Scientific RevolutionMrEHsieh100% (2)

- History of ScienceDocument103 pagesHistory of Scienceapi-25885481100% (1)

- 8 in The HundredDocument2 pages8 in The HundredVũ PhạmNo ratings yet

- Isaac NewtonDocument17 pagesIsaac Newtonkhoa280197No ratings yet

- Scientific Revolution With Referance To Individual GeniusesDocument15 pagesScientific Revolution With Referance To Individual Geniusesvanshikavivek820No ratings yet

- Top 1000 Baby Girl NamesDocument7 pagesTop 1000 Baby Girl NamesmarkgranNo ratings yet

- CH 17 PalmDocument5 pagesCH 17 Palmmarkgran100% (2)

- XVIII The Apparent Victory of Democracy 97. The Advance of Democracy After 1919 Pp. 740-745Document4 pagesXVIII The Apparent Victory of Democracy 97. The Advance of Democracy After 1919 Pp. 740-745markgran100% (2)

- The Federalist PapersDocument400 pagesThe Federalist PapersGuy Razer100% (7)

- What Has Worked in InvestingDocument60 pagesWhat Has Worked in InvestinggsakkNo ratings yet

- Chapter XIV. European Civilization, 1871-1914Document5 pagesChapter XIV. European Civilization, 1871-1914AdamNo ratings yet

- Remodeling Contractor Basic Marketing PlanDocument20 pagesRemodeling Contractor Basic Marketing PlanmarkgranNo ratings yet

- Chapter XV: Europe's World Supremacy: 78. Imperialism: Its Nature and Causes Pp. 642-650Document4 pagesChapter XV: Europe's World Supremacy: 78. Imperialism: Its Nature and Causes Pp. 642-650markgran100% (2)

- Chapter IX. The French Revolution: 41. Backgrounds Pp. 351-354Document6 pagesChapter IX. The French Revolution: 41. Backgrounds Pp. 351-354markgran100% (2)

- Chapter 13: The Consolidation of The Large Nation-States, 1859-1871Document5 pagesChapter 13: The Consolidation of The Large Nation-States, 1859-1871markgran100% (2)

- Study Guide Chapter VI. The Struggle For Wealth and Empire Pp. 250-287Document4 pagesStudy Guide Chapter VI. The Struggle For Wealth and Empire Pp. 250-287markgranNo ratings yet

- Chapter VIII: The Age of The Enlightenment Pp. 314-360Document5 pagesChapter VIII: The Age of The Enlightenment Pp. 314-360markgran100% (2)

- Chapter V. The Transformation of Eastern Europe, 1648-1740 (Document5 pagesChapter V. The Transformation of Eastern Europe, 1648-1740 (markgranNo ratings yet

- RIPA Iconologia Vol 1Document490 pagesRIPA Iconologia Vol 1volodeaTis100% (3)

- Tides WebquestDocument3 pagesTides Webquestapi-264886115No ratings yet

- Blue Self Existing Eagle 4Document4 pagesBlue Self Existing Eagle 4mimi ciciNo ratings yet

- Kinetic Energy and Gravitational Potential EnergyDocument3 pagesKinetic Energy and Gravitational Potential EnergyMark ProchaskaNo ratings yet

- Svi Aspekti MesecaDocument16 pagesSvi Aspekti MesecaJelena HalasNo ratings yet

- Leena August1984Document1 pageLeena August1984communicatetoousNo ratings yet

- History of Plate Tectonics Ppt-1Document26 pagesHistory of Plate Tectonics Ppt-1Radin Tagarino100% (1)

- Dice Games For Class by SlidesgoDocument50 pagesDice Games For Class by SlidesgoDamna IsidroNo ratings yet

- 10 TriasDocument27 pages10 TriasSyifa Oktaviani SofwanNo ratings yet

- Acceleration: Definition of Acceleration For Linear V T GraphsDocument50 pagesAcceleration: Definition of Acceleration For Linear V T GraphssomansambavanNo ratings yet

- Kepler's Law PDFDocument25 pagesKepler's Law PDFJenny May SudayNo ratings yet

- Annual Horoscope by Rajendra NimjeDocument3 pagesAnnual Horoscope by Rajendra NimjeDilip KiningeNo ratings yet

- 9 English FA 1 Set ADocument2 pages9 English FA 1 Set ASitaNo ratings yet

- AyurdayaDocument2 pagesAyurdayamahadp08100% (1)

- Carl Friedrich Gauss - WikipediaDocument61 pagesCarl Friedrich Gauss - WikipediaAnurag SharmaNo ratings yet

- Hello World!: Here Is Where Your Presentation BeginsDocument11 pagesHello World!: Here Is Where Your Presentation BeginsQuân LươngNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Space ExplorationDocument6 pagesChapter 10 Space ExplorationNaveen AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Eye Can See Pratham FKBDocument21 pagesEye Can See Pratham FKBJaime MNo ratings yet

- The Internet Top 100 SF Fantasy ListDocument5 pagesThe Internet Top 100 SF Fantasy ListJohannDoelerNo ratings yet

- CHEM340 Tut AAS With AnswersDocument4 pagesCHEM340 Tut AAS With AnswersAlex Tan100% (3)

- Science Lesson AstromyDocument3 pagesScience Lesson Astromythe.efroNo ratings yet

- Astrological Report: Birth Time RectificationDocument3 pagesAstrological Report: Birth Time RectificationRajendra SinghNo ratings yet

- PDF Padlet 6 Raman Spectroscopy Sept2014Document22 pagesPDF Padlet 6 Raman Spectroscopy Sept2014Maxvicklye RaynerNo ratings yet

- Transformations - Studies in The History of Science and Technology William R. Newman, Anthony Grafton - Secrets of NatureDocument452 pagesTransformations - Studies in The History of Science and Technology William R. Newman, Anthony Grafton - Secrets of NatureRomano BolkovićNo ratings yet

- Will For Future - PpsDocument19 pagesWill For Future - PpsCovarrubias Saavedra DamianNo ratings yet

- The Return of The Iron Man-Iron Man Chapter 5Document6 pagesThe Return of The Iron Man-Iron Man Chapter 5wemrahNo ratings yet

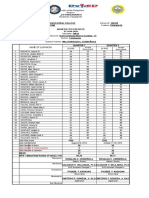

- Quarter Test Result For Shs Sy 2019 20 1st SemDocument24 pagesQuarter Test Result For Shs Sy 2019 20 1st SemRonaliza CerdenolaNo ratings yet

- Newton's Laws of Motion - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument13 pagesNewton's Laws of Motion - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediabmxengineeringNo ratings yet

- Soal TOEFL StructureDocument24 pagesSoal TOEFL Structuresrinurul kuraini100% (1)

- Deepak BisariaDocument6 pagesDeepak BisariaShivam VinothNo ratings yet