Effects of Sports Participation and Sports-specific Self-esteem

on Academic Performance: A Research Design

Shane J. Ralston

Pennsylvania State University Hazleton

sjr21@psu.edu

Word count: 2,095

Working Draft: comments welcome.

Please do not cite or quote without permission.

Abstract

Poor academic performance among students at U.S. colleges and universities has become a

matter of increasing concern. Research shows that SAT scores have declined in recent decades

and high school students are increasingly coming to college unprepared. This phenomenon is

troubling because of the much larger crisis looming in American society. If college-educated

citizens lack the basic skills and requisite competencies that would enable them to contribute to

the success of U.S. companies, then it is likely that American dominance in the global marketplace will soon decline. As a result of this skills crisis, more and more jobs held by Americans

in American companies are being exported to better educated foreign workers in foreign

countries, such as Dell Computers’ removal of customer support representative positions to India.

This study aims to determine why the academic achievement of American college and university

students is currently in such a poor state. Past research has explored many possible explanations

for the academic underperformance of college and university students. Some researchers have

connected poor academic performance with specific types of student behavior, such as

delinquency, failure to work hard, and lack of self-control. Others have linked lower academic

achievement with particular student attributes, such as minority racial status, a sense of alienation

from the academic community, inability to form strong support networks and anti-social

personality characteristics. One possible explanation that has received too little attention from

researchers is that more time spent participating in intramural and intercollegiate athletics

coupled with the consequent rise in sports-specific self-esteem causes student-athletes to perform

poorly in their studies.

Key Terms: college sports, academic performance, self-esteem.

1

�Effects of Sports Participation and Sports-specific Self-esteem

on Academic Performance: A Research Design

I. Statement of the Problem

Poor academic performance among students at U.S. colleges and universities has become a

matter of increasing concern. Research shows that SAT scores have declined in recent decades

and high school students are increasingly coming to college unprepared.1 This phenomenon is

troubling because of the much larger crisis looming in American society. If college-educated

citizens lack the basic skills and requisite competencies that would enable them to contribute to

the success of U.S. companies, then it is likely that American dominance in the global marketplace will soon decline. As a result of this skills crisis, more and more jobs held by Americans

in American companies are being exported to better educated foreign workers in foreign

countries, such as Dell Computers’ removal of customer support representative positions to

India.2 This study aims to determine why the academic achievement of American college and

university students is currently in such a poor state.

Past research has explored many possible explanations for the academic

underperformance of college and university students. Some researchers have connected poor

academic performance with specific types of student behavior, such as delinquency, failure to

1

See A. Astin, “Undergraduate Achievement and Institutional ‘Excellence’,” Science, vol. 161 (April 1968):661-8.

Also, see H. Walberg, B. Strykowski, E. Rovai, and S. Hung, “Exceptional Performance,” Review of Educational

Research, vol. 54 (Spring 1984): 87-112.

2

In March 2005 Dell Computers had 55, 200 employees, 30, 600 or 55% of which are overseas. Most of their

customer support centers were relocated to India in 2004. See S. Pruitt, “Dell’s Workforce Moves Abroad,” PC

World (Tuesday, April 13 2004), p. 1, available at <www.pcworld.com/article/id,115648page,1/article,html?tk=cx041304a>. See also G. J. Koprowski, “Dell Sends Most New Jobs Overseas,”

www.Technews.com (April 14 2004), available at <www.crmbuyer.com/story/33421.html>. Also, see A. Howard,

“College Experiences and Managerial Performance,” Journal of Applied Psychology Monograph, vol. 71 (1986):

530-2.

2

�work hard, and lack of self-control.3 Others have linked lower academic achievement with

particular student attributes, such as minority racial status, a sense of alienation from the

academic community, inability to form strong support networks and anti-social personality

characteristics.4 One possible explanation that has received too little attention from researchers

is that more time spent participating in intramural and intercollegiate athletics coupled with the

consequent rise in sports-specific self-esteem causes student-athletes to perform poorly in their

studies.

A review of the literature on the relationship between athletic participation and academic

performance reveals mixed findings. Some studies demonstrate that participation in college

athletics depresses academic achievement. For instance, Adler and Adler confirm that the

relationship between athletic participation and academic performance among college athletes is a

negative one. Instead of going to college with the plan of performing exceptionally in sports and

poorly in academics, most student-athletes begin college hopeful and idealistic about their

academic potential and then become disillusioned after they experience repeated academic

failures. 5 Likewise, Blann concludes that “participation in intercollegiate athletics at a high

level of competition may detrimentally affect students’ ability to formulate mature educational

3

See E. Maquin and R. Loeber, “Academic Performance and Delinquency,” Crime and Justice, vol. 20 (1996): 145264. On how the failure to work hard causes underperformance, see W. Rau and A. Durna, “The Academic Ethic

and College Grades: Does Hard Work Help Students ‘Make the Grade’?” Sociology of Education, vol. 73, no. 1

(January 2000):19-38. On the connection between students’ lack of self-control and lowered academic achievement,

see C. E. Ross and B. A. Broh, “The Roles of Self-esteem and the Sense of Personal Control in the Academic

Achievement Process,” Sociology of Education, vol. 73, no. 4 (October 2000): 270-84.

4

See R. P. Brown and M. N. Lee, “Stigma Consciousness and the Race Gap in College Academic Achievement,”

Self and Identity, vol. 4, no. 2 (April-June 2005): 149-57. On alienation, see K. E. Voelkl, “Identification with

School,” American Journal of Education, vol. 105, no. 3 (May 1997):294-318. On the inability to form strong

support networks, see A. Townsend, “It Takes a Network of Support; Collective Efforts Help Ensure Local

Graduates Succeed in College,” Plain Dealer (June 27, 2006): A1. On anti-social personality characteristics, see

Edward Kifer, “Relationships between Academic Achievement and Personality Characteristics: A QuasiLongitudinal Study,” American Educational Research Journal, vol. 12, no. 2 (Spring 1975):191-210.

5

See P. Adler and P. A. Adler, “From Idealism to Pragmatic Detachment: The Academic Performance of College

Athletes,” Sociology of Education, vol. 58, no. 4 (October 1985): 241-250.

3

�and career plans.”6 Also, Maloney and McCormick found that classroom achievements by

college athletes are significantly less impressive than the achievement of their non-athletic peers.7

However, other studies show that participation in college sports either has no relationship with

academic achievement or, contrary to the first set of studies, actually promotes academic success.

For example, Hanks and Eckland find that there is no support for the conclusion that there is a

negative relationship between participation in college athletics and academic performance.

Instead, they show that there is no relevant relationship between the two variables: “Athletics

appear neither to depress nor to especially enhance the academic performance of its

participants.”8 In addition, Otto and Alwin found that athletic participation has a positive

relationship with educational goal creation and achievement. To explain the positive

relationship, they suggest that athletic participation may socialize students to develop (i) a work

ethic that carries over to the classroom and (ii) valuable social skills that raise their self-esteem.9

Finally, Spreitzer and Pugh infer from the findings of their study “that sports involvement is not

necessarily detrimental to academic pursuits.” Contrary to the view that sports participation and

educational goal-setting and achievement are negatively related, sports participation can

positively impact a student’s self-image and status within a community, motivating that person to

attend college and perform exceptionally in her studies in order to further elevate that self-image

and community status.10

6

See F. W. Blann, “Intercollegiate Athletic Competition and Students’ Educational and Career Plans,” Journal of

College Student Personnel, vol. 26, no. 2 (March 1985): 115-118, 118.

7

M. T. Maloney and R. E. McCormick, “An Examination of the Role That Intercollegiate Athletic Participation

Plays in Academic Achievement: Athletes’ Feats in the Classroom,” The Journal of Human Resources, vol. 28, no. 3

(Summer 1993): 555-570.

8

M. P. Hanks and B. K. Eckland, “Athletics and Social Participation in the Educational Attainment Process,”

Sociology of Education, vol. 49, no. 4 (October 1976): 271-294, 292.

9

Otto, L.B. and D.F. Alwin, “Athletics, Aspirations, and Attainments,” Sociology of Education, vol. 50, no. 2 (April

1977): 102-113.

10

See E. Spreitzer and M. Pugh, “Interscholastic Athletics and Educational Expectations,” Sociology of Education,

vol. 46, no. 2 (Spring 1973): 171-182, 181.

4

�The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between participation in college

athletics, sports-specific self-esteem and academic achievement. An additional study is needed

because currently a gap exists in the literature with respect to how athletic participation

influences sports-specific self-esteem and, in a path-dependent fashion, causes poor academic

performance. Most studies that comment on self-esteem hypothesize a positive, not a negative,

relationship between sports participation and academic performance.11 Overall, the problem of

academic underperformance not only portends an impending skills crisis or “brain drain” in

American society, it also threatens to undermine the values and missions of higher education

institutions. Accommodating these institutions’ sometimes conflicting commitments to the

athletic achievement and academic excellence of their students, Tobin argues, is a first step in

defusing the threat: “One of the most difficult challenges that higher education faces is preserving

the contributions that athletics makes without losing sight of the fact that colleges and

universities are primarily academic institutions.”12

II. Research Hypotheses

H1: As the hours that college students participate in sports increase, the degree to which college

students report that their self-image is dependent on their involvement in sports increases.

Rationale: When student-athletes invest more time in training for and playing in either

intercollegiate or intramural college sports, they become more proficient and competitive.

Because they invest more time in sports participation compared to the time spent on other

activities, they derive a greater sense of self-worth from the sports activity.

11

See, for instance, Otto and Alwin, “Athletics, Aspirations, and Attainments,” as well as Spreitzer and Pugh,

“Interscholastic Athletics and Educational Expectations.”

12

See E. M. Tobin, “Athletics in Division III Institutions: Trends and Concerns,” Phi Kappa Phi Forum, vol. 85, no.

3 (Fall 2005): 24-7.

5

�H2: As the degree to which college students report that their self-image is dependent on their

involvement in sports increases, their academic performance decreases.

Rationale: The increased self-esteem that student-athletes derive from participating in college

athletics leads them to prioritize sports achievement over academic achievement. As a

consequence, their academic performance suffers.

H3: As the hours that college students participate in sports increase, their academic performance

decreases.

Rationale: One possibility is that the relationship is path-dependent, so that as more time is

invested in sports participation, sports-specific self-esteem also increases. Because self-esteem or

self-image is dependent on participation in sports, students will prioritize athletic over academic

achievement. So, student-athletes who accept this prioritization perform poorly in their courses

and, consequently, their grades on exams drop. Another possibility is that self-esteem is

irrelevant. Instead, student-athletes’ greater investment of time in sports detracts from the time

they have to spend on their studies, thereby lowering their academic achievement. In this case,

path-dependence is absent.

6

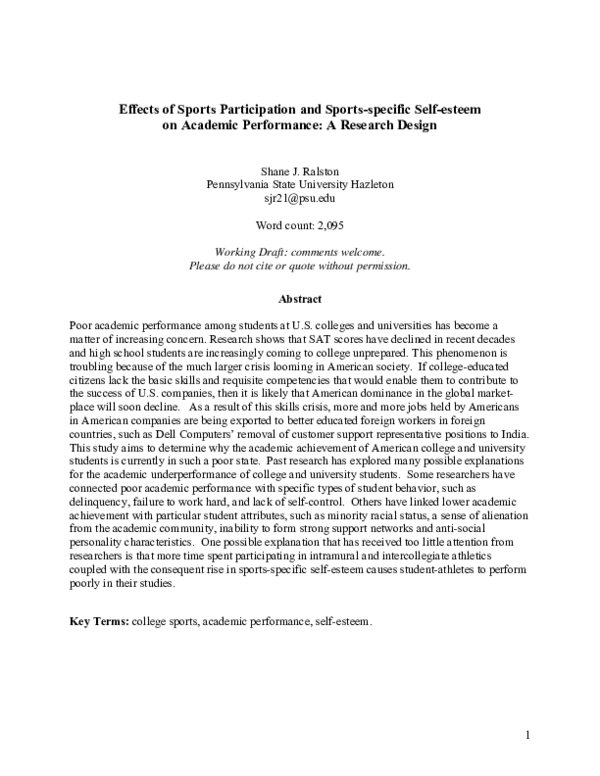

�Figure 1: Diagram of the Hypothesized Causal Paths

Concept:

Sports

Participation

Concept:

Sports-specific

Self-esteem

Concept:

Academic

Performance

IV:

Hours per

Week Spent

Participating

in Sports

D/IV:

Degree to

which Selfimage is

Sportsdependent

DV:

Grade on

First

Exam

1- Less than 1 hour

2- 1-5 hours

3- 6-10 hours

4- 11-15 hours

5- 16-20 hours

6- More than 20

+

4- Very dependent

3- Somewhat

dependent

2- Not dependent

1- No participation

in sports

--

1- A: 90-100

2- B: 80-89.

3- C: 70-79.

4- D: 60-69.

5- Less than 60

As indicated in Figure 1, participation in sports serves as an independent variable in H1

and H3 and is operationally defined in terms of hours spent participating in sports. For purposes

of H2, sports-specific self-esteem is operationalized in terms of the level of self-image which

depends on their involvement in sports, as reported by students in response to a survey question.

For purposes of H2 and H3, academic performance serves as the dependent variable and is

operationally defined by the grade that the student received on his or her last exam.

7

�III. Methodology

Research and Sample Populations

For this study, the research population consists of all undergraduate students at the

University of Montana during the fall semester 2006. In order to generalize about this

population, approximately 100 undergraduate students will be sampled from an introductory

Political Science, PSC 130 International Relations, on November 3, 2006. Due to limitations of

money and time, a simple random sample or stratified random sample cannot be conducted to

ensure that the sample is adequately representative of the larger population.

Data Collection

Data will be collected by distributing a questionnaire to students, which they will

complete and return to the researcher. The questionnaire has three questions on it (see Appendix

A: Survey Questions). The questionnaire will be explained to the students as a study conducted

by graduate students in PSC 502 Research Methods with no particular purpose except to serve as

practice exercise in statistical analysis. Respondents will be told that the questionnaire should be

answered truthfully and that participation in the survey is voluntary and anonymous.

Data Analysis

Three correlational analyses will be conducted using Pearson’s r as the statistical

coefficient of correlation. In the first analysis, H1 will be tested by correlating the responses to

question 1 (how many hours per week are spent participating in college sports) with the

responses to question 2 (how dependent is self image on involvement in college sports). In the

second analysis, H2 will be tested by correlating the responses to question 2 to the responses to

question 3 (the grade received on the first exam taken in the course). In the third and final

8

�analysis, H3 will be tested by correlating the responses to question 1 to the responses to question

3.

Overall, the objective is to conduct a path analysis. If the relationship between responses

to questions 1 and 2 (H1) as well as 2 and 3 (H2) are statistically significant and stronger than the

relationship between 1 and 3 (H3), then it can be concluded with some confidence that the

relationship between the three variables is path-dependent. If not, then there is no evidence for

path dependency. However, even if no evidence for path-dependency can be found, it is still

possible that either the relationship between the responses to question 2 and question 3 (H2) or

the relationship between the responses to question 1 and 3 (H3) will be statistically significant.

Limitations

There are multiple limitations to the research design that could potentially undermine the

validity of the findings: (i) the inadequacy of a convenience sample, (ii) the shortcoming of too

small of a sample size and (ii) the limited indicator of academic performance.

First of all, as mentioned earlier, shortages of time and money make it too difficult to

secure a random sample or stratified random sample. These sampling strategies would

significantly increase the likelihood that the eventual sample would be representative of the larger

population. Even though the convenience sample employed in this design is not random, there is

nevertheless reason to believe that it will be representative of the population. Because the

convenience sample is taken from a General Education course (PSC 130 International Relations),

the sample is expected to contain student-respondents who have diverse majors and are at many

stages in their college careers. Therefore, the inadequacy of the convenience sample would not

be expected to threaten the validity of the research findings. Nonetheless, if the research were to

be duplicated, obtaining a random or stratified random sample would be preferable.

9

�Secondly, too small of a sample size is also a limitation that could undermine the validity

of the results. Ideally, the sample size ought to number at least three-hundred-eighty-four

surveys in order for the researcher to be 95% confident (plus or minus 5%) that the broader

population would respond in the same way as the sample. Since the sample size is significantly

less than three-hundred-eighty-four (approximately 100 respondents), the results of the sample

cannot be generalized to the population with absolute confidence. So, if the study were to be

duplicated, a sample size of at least three-hundred-eighty-four would be required to ensure the

external validity of the relationship between the sample and the population.

Lastly, this study employs one and only one grade on a single test as an indicator of

academic performance. Typically, other studies rely on Grade Point Averages (GPAs),

Scholastic Aptitude Tests (SATs) and other generally accepted indicators, whether alone or

together in an index, in order to accurately measure academic performance. Unfortunately, since

freshman students do not have Grade Point Averages as of yet, it was impossible to use GPA as

an indicator of academic performance. Although performance on a single exam is a poor

indicator of overall academic performance, it is the only one available. So, even if an

independent variable can be correlated with the dependent variable of academic performance

(particularly in the case of testing H2 and H3), the validity of this finding is still open to question.

Therefore, in order to ensure the validity of the results, the study would need to be replicated with

multiple indicators of the dependent variable (academic performance).

10

�Appendix A: Survey Questions

1. How many hours per week do you spend participating in either intramural or

intercollegiate sports including training/practicing for these sports?

___ less than one hour

___ 1-5 hours

___ 6-10 hours

___ 11-15 hours

___ 16-20 hours

___ more than 20

2. To what degree do you believe that your self image (self worth or self esteem) is

dependent on your involvement in intramural or intercollegiate sports?

___ very dependent

___ somewhat dependent

___ not dependent

___ I do not participate in sports

3. What grade did you receive on the first exam you took in this course?

___ A: 90-100

___ B: 80-89

___ C: 70-79

___ D: 60-69

___ less than 60

11

�

Shane J Ralston

Shane J Ralston