Critical Thinking:: Strategies For Improving Student Learning, Part II

Critical Thinking:: Strategies For Improving Student Learning, Part II

Uploaded by

dgsCopyright:

Available Formats

Critical Thinking:: Strategies For Improving Student Learning, Part II

Critical Thinking:: Strategies For Improving Student Learning, Part II

Uploaded by

dgsOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Critical Thinking:: Strategies For Improving Student Learning, Part II

Critical Thinking:: Strategies For Improving Student Learning, Part II

Uploaded by

dgsCopyright:

Available Formats

Critical Thinking: testing these two students (and they pass), announce to the class that X

and Y have passed and that they are now “certified” to test others. How-

Strategies for Improving

ever, anyone “certified” by a student tester must be “spot-tested” by the

instructor on one item. If any such student fails the spot test, the person

Student Learning, Part II

who certified them is “de-certified” (and must repeat the exam). Everyone

who passes becomes a certifier and gets paired with a student who has not

taken the oral test.

By this method, the instructor only tests the first two students. The rest

of the process involves directing “traffic” and spot-checking those who are

By Richard Paul and Linda Elder “certified” by a peer. During this assessment the tester should be look-

ing for a beginning understanding of the concepts and the ability to give

In the last column we focused (as a primary goal of instruction) on the examples of the concept. Since the students who pass become “certifiers”

importance of teaching so that students learn to think their way into and or “tutors” and are assigned to assess other students (or tutor them), ev-

through content. We stressed the need for well-designed daily structures eryone gets multiple experiences explaining, and hearing explanations of,

and tactics for fostering deep learning, offering three strategies as exam- the basic vocabulary.

ples. In this column, we provide four additional strategies. We give a vocabulary list to the students on the first day of class so they

There is no perfect technique for fostering critical thinking, no ideal know exactly which concepts they will be expected to explain during the

method for engaging the intellects of students. The strategies detailed in oral exam and learn the most basic vocabulary early in the course, vocabu-

this column suggest some possible ways for helping students take com- lary that is then used on a daily basis in class. Individual teachers might

mand of what they are learning, integrate and apply what they are learn- want to modify this exam by giving parts of it during or after each chapter

ing, and appropriately question what they are learning. These approaches (of the textbook).

to teaching and learning can be modified in any number of ways. And of

course, any one strategy, if used, would need to be integrated into a well- Idea # 5: Teach Students How to Assess

designed course plan.

Most importantly, each strategy presupposes the use of critical think- Their Listening

ing concepts and principles to be effective. Each strategy presupposes that Since students spend a good deal of their time listening, and since de-

the only way to learn content deeply and truly is to think it into individual veloping critical listening skills is difficult to achieve, it is imperative that

thinking, to connect it with other important ideas, and to apply it to every- faculty design instruction that fosters critical listening. This is best done by

day life issues and problems (Paul & Elder, 2006). holding students responsible for their listening in the classroom. Here are

some structures that help students develop critical listening abilities:

Idea # 4: Teach Students How to Assess

First Strategy

Their Speaking Call on students regularly and unpredictably, holding them responsible

In a well-designed class, students often engage in oral communication. either to ask questions they are formulating as they think through the con-

They articulate what they are learning: explaining, giving examples, pos- tent or give a summary, elaboration, or example of what others have said.

ing problems, interpreting information, tracing assumptions, and so forth.

They learn to assess what they are saying, becoming aware of when they Second Strategy

are being vague, when they need an example, and when their explanations Ask every student to write down the most basic question they need an-

are inadequate. Following are three general strategies to teach students to swered in order to understand the issue or topic under discussion. Then

assess their speaking abilities. collect the questions (to see what they understand or don’t understand

about the topic). Or you might: (a) call on some of them to read their ques-

First Strategy: Students Teaching Students tions aloud, or (b) put them in groups of two with each person trying to

One of the best ways to learn is to try to teach someone else. Trouble ex- answer the question of the other.

plaining something often indicates a lack of clarity about the concept. Through activities such as these students learn to monitor their listen-

ing, determining when they are and are not following what is being said.

Second Strategy: Group Problem Solving This should lead to their asking pointed questions. Reward students for

By putting students in a group and giving them a problem or issue to work asking questions when they do not understand what is being said.

on together, their mutual articulation and exchanges will often help them

to think better. They often correct each other and so learn to “correct” Idea # 6: Design Tests with the Improvements of

themselves. Make sure students are routinely applying intellectual stan-

dards to their thinking as they discuss issues. Student Thinking in Mind

In planning tests, be clear about the intended purpose. A test in any sub-

Third Strategy: Oral Test on Basic Vocabulary ject matter should determine the extent to which students are developing

One complex tactic that aids student learning is the oral test. Give students useful and important thinking skills with respect to that subject. The best

a vocabulary list and time to study the key concepts for the course. Then tests are those most reflective of the kinds of intellectual tasks students will

put them into groups of twos or threes and have them take turns explain- perform when they apply the subject matter to professional and personal

ing the concepts to each other, encouraging them to assess each other’s issues in the various domains of their lives. Since multiple-choice tests are

explanations. Wander about the class listening in, and choose two students rarely useful in assessing life situations, they are rarely the best overall test,

who seem prepared for the oral exam. Stop the class and announce that the though they can assess some supplementary understandings at an entry

oral test is going to begin and that “X” and “Y” will be tested first. After level.

34 JOURNAL of DEVELOPMENTAL EDUCATION

One type of test that does target more realistic skills is an analytic test If students are to become disciplined thinkers, they need to do a good

of the students’ ability to take thinking apart and elaborate accurately each deal of active thinking to take ownership of the content they are learning.

of its elements. Another type assesses the students’ ability to evaluate those Teachers often make the mistake of thinking that students learn well only

elements using intellectual standards. In other words, students should when instructors spend hours preparing for class (e.g., learning informa-

learn how to analyze and evaluate thinking within the subjects they are tion they then tell to students). But learning to think well requires many

studying. opportunities for practice in thinking through problems and issues and in

applying concepts in one’s thinking to real life experiences. Students can

Analyzing Thinking do this only when classroom structure design requires them to work to

After students have learned the fundamentals of critical thinking, and understand and apply the fundamentals of the subject. Spoon feeding pas-

have reasoned through the logic of several teacher-supplied chapters and/ sive students is a useless activity. Try random sampling grading to reduce

or articles, have them figure out the logic of an article during one class the overall amount of grading.

period (or the logic of a section of the textbook). This type of test can de-

termine the extent to which they can accurately state an author’s purpose, Conclusion

key question, information, conclusions, concepts, assumptions, implica-

These are just four of many strategies that can be used to foster deep think-

tions, and point of view.

ing through content. For additional strategies, see our previous and next

few columns as well as cited literature.

Evaluating Thinking

Having completed part one above, students could evaluate the author’s

logic using the following format (Paul & Elder, 2008). References

• Is the question at issue clear and unbiased? Does the expression of the Paul, R. & Elder, L. (2006). Critical thinking: Tools for taking charge of your

question do justice to the complexity of the matter at issue? learning and your life. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

• Is the writer’s purpose clear? Paul, R. & Elder, L. (2006). The international critical thinking reading and

writing test. Dillon Beach, CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking Press.

• Does the writer cite relevant evidence, experiences, and/or informa-

Paul, R. & Elder, L. (2008). The miniature guide to critical thinking concepts

tion essential to the issue?

and tools. Dillon Beach, CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking Press.

• Does the writer clarify key concepts when necessary?

• Does the writer show sensitivity to what he or she is assuming or tak- Richard Paul is director and Linda Elder is executive director of research

ing for granted? (Insofar as those assumptions might reasonably be and professional development of the Center for Critical Thinking at Sonoma

questioned)? State University, Rohnert Park, CA 94928.

• Does the writer develop a definite line of reasoning, explaining well

how he or she is arriving at his or her conclusions?

• Does the writer show sensitivity to alternative points of view or lines of

reasoning? Does he or she consider and respond to objections framed IN

from other points of view? DEVELOPMENTAL

• Does the writer show sensitivity to the implications and consequences EDUCATION

of the position he or she has taken? D. Patrick Saxon and

Barbara J. Calderwood, Coeditors

This sort of test, attempts to determine whether students are learning

Published by Appalachian State University Volume 21, Issue 4, 2007

to enter viewpoints that differ from their own. Create multiple tests using

Organizational Structure and Institutional Location

this same format by changing only the written piece to be analyzed (select- of Developmental Education Programs

ing, of course, pieces whose point of view is significantly different from

that of most students). Of course, this test does not determine whether a ...reviewing current research related

By D. Patrick Saxon and Hunter R. Boylan

Institutions of higher education exhibit a variety of approaches decentralized developmental education structures; 38% of

student will actually empathize with opposing views in real life situations

to developmental education

to structuring and locating developmental education programs. programs were centralized. In a study of 45 two-year and technical

Program structure has an impact on program effectiveness due to colleges, 44% had centralized programs (Gerlaugh, Thompson,

its influence on institutional integration and coordination. It also Boylan, & Davis, 2007).

(Paul & Elder, 2006). affects the amount and type of collaboration and communication

in a newsletter format.

that takes place among its constituents. Program location (as

defined by reporting structure) may affect program visibility, Advantages and Disadvantages

perceived status, and resource allocation decisions. Ultimately, of Centralized Programs

these variables have an impact on student success.

Idea # 7: Make the Course Work-Intensive Organizational Structure

The research literature suggests that centralized program

structures increase the chances of student success (Boylan, 2002;

for the Students Boylan, Bliss, & Bonham, 1997; Littleton, 2000). Centralization

$15/volume (4 issues)

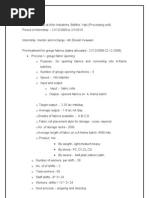

How are programs structured in U.S. higher education? Saxon, contributes to higher developmental pass rates and increased student

Sullivan, Boylan, and Forrest (2005) report from a national study retention. These benefits likely stem from increased coordination

conducted more than 10 years ago that 52% of all developmental and communication among the personnel involved in delivering

There are two significant mistakes to avoid. The first is designing classes so programs are centralized. This figure includes 2- and 4-year

colleges. Thirteen percent of successful developmental programs

developmental courses and learning services (Boylan, 2002).

Centralization enables proximity of personnel and, therefore,

students can pass them without thinking deeply about the content of the in Texas report having fully centralized programs. This information more collaborative efforts in planning and development.

Centralized programs are more likely to be staffed with

Published by the

is from a study of 43 Texas community colleges and universities

full-time faculty, and they may offer more comprehensive

course. The second is designing classes so that the instructor must work identified as successful based on Texas Academic Skills Program

(TASP) student performance (Boylan & Saxon, 1998). support services. Teachers may also be more effective and

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) offers have higher motivation to work with underprepared students

harder than the students.

National Center for Developmental Education

more comprehensive data on the organization of “remedial” if developmental education is their primary task (Perin, 2002).

courses (National Center for Education Statistics, 2003). An Centralized programs also contribute to easier access for students.

In a class that consists mainly of lectures with periodic quizzes and assumption of this research is that courses offered in separate

divisions and in learning centers are considered centralized.

Typically faculty and support services are located proximally to

developmental classrooms. This enables increased interaction

examinations, students can often get a passing grade by “cramming” the Courses described as housed in their traditional academic

departments are considered decentralized. These definitions apply

between students and program resources. Increased integration

and interaction among support services contributes to student

For subscription information visit

success in developmental courses (Boylan, Bonham, Claxton, &

night before quizzes and tests. Many students have developed cramming in this article as well (see Table 1 for NCES data categorized by

subject, structure, and institution type). Bliss, 1992).

Quirk (2005) suggests that developmental program

skills to the point that they misleadingly create the appearance of under- Table 1 administrators may have better access to campus planning

http://www.ncde.appstate.edu

NCES Remedial Education Course Data

and leadership when their program is centralized. Klicka

standing a body of content when they don’t. The problem is that most

Institution Reading Writing Mathematics

Type (1998) concurs and adds that centralization ensures

Centralized Decentralized Centralized Decentralized Centralized Decentralized

visibility and attention during program resource allocation.

All One may also speculate that services and resources

cramming feeds only the short-term memory. Students adept at it will say institutions 41% 57% 29% 70% 26% 72%

designated solely for the delivery of developmental

Public

2-year 41% 58% 36% 64% 35% 64% education are easier to account for and to evaluate for

things like, “I got an A in Statistics last semester, but don’t ask me any Private

2-year - - 14% 81% - 87%

effectiveness.

On the other hand, certain disadvantages may result

questions about it. I’ve forgotten most of what I learned.” Public

4-year 42% 56% 27% 70% 25% 73%

from a centralized developmental program structure.

Perin (2002) suggests that aligning the content of

Private

4-year 43% 55% 23% 76% 19% 81% developmental courses with college-level courses may

be more difficult to manage in a centralized program.

Note. Dashes indicate data not available. The data in Table 1 are adapted from “Remedial The coordination and effectiveness of paired-course

education at degree-granting postsecondary institutions in Fall 2000,” by the National Center offerings may suffer as well. A centralized program is

VOLUME 32, ISSUE 2 • WINTER 2008 for Education Statistics (2003), Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

35

probably more expensive to operate than a decentralized

one, or at least the components of a centralized program are

According to the NCES data, it appears that 2-year schools

are less likely to centralize their programs. In a national study more clearly delineated, making obvious its scope and degree of

of community colleges, Shults (2000) found that 61% had accountability. It certainly is more visible to administrators who

1

You might also like

- 5 E's APPROACHDocument31 pages5 E's APPROACHRainiel Victor M. Crisologo100% (6)

- Dutch East India Company Merchants at The Court of Ayutthaya PDFDocument297 pagesDutch East India Company Merchants at The Court of Ayutthaya PDFSherry Kwok100% (1)

- Totoro PatternDocument15 pagesTotoro PatternJasguar AncestralNo ratings yet

- Strategy Implementation Module 4Document30 pagesStrategy Implementation Module 4sapnanibNo ratings yet

- Grit, Tenacity and PerseveranceDocument126 pagesGrit, Tenacity and PerseveranceJohn Jensen100% (2)

- Milan Critical Reflection Essay 2Document5 pagesMilan Critical Reflection Essay 2api-548980525No ratings yet

- MGMT 3P98 Course Outline S20Document6 pagesMGMT 3P98 Course Outline S20Jeffrey O'LearyNo ratings yet

- GCSE Composition 1 TaskDocument5 pagesGCSE Composition 1 TaskScott AdelmanNo ratings yet

- Integrity ActionDocument28 pagesIntegrity ActionskycrownNo ratings yet

- Notes To The Excellent Book The Money Game by Adam SmithDocument8 pagesNotes To The Excellent Book The Money Game by Adam SmithintothewoodsNo ratings yet

- Political Dynasties and ElectionDocument114 pagesPolitical Dynasties and ElectionalicorpanaoNo ratings yet

- Unmasking CorruptionDocument1 pageUnmasking Corruptiondanicawashington00No ratings yet

- Anti-Bribery and Corruption HandbookDocument16 pagesAnti-Bribery and Corruption HandbookZiaulNo ratings yet

- How To Succeed in Graduate SchoolDocument15 pagesHow To Succeed in Graduate SchoolEloiseNo ratings yet

- Blueprint For Success in College and CareerDocument506 pagesBlueprint For Success in College and CareerAnonymous yQwfmbm100% (1)

- Infj ADocument12 pagesInfj APhuong Ta MaiNo ratings yet

- Assessment: First Things First ConfidenceDocument2 pagesAssessment: First Things First ConfidenceKremena KoevaNo ratings yet

- 14.ten Metacognitive Teaching StrategiesDocument23 pages14.ten Metacognitive Teaching StrategiesStephen100% (2)

- Educators File Year 2003Document4 pagesEducators File Year 2003sszmaNo ratings yet

- Unit 05Document27 pagesUnit 05Tanzeela BashirNo ratings yet

- 20 Simple Assessment Strategies You Can Use Every Day: Strategies To Ask Great QuestionsDocument13 pages20 Simple Assessment Strategies You Can Use Every Day: Strategies To Ask Great Questionsrosmery15No ratings yet

- Lesson PlanningDocument46 pagesLesson PlanningZarahJoyceSegovia100% (1)

- Can You Add Faster Than A 5 Years Old?Document27 pagesCan You Add Faster Than A 5 Years Old?Michael DomanaisNo ratings yet

- Module 3Document45 pagesModule 3alma roxanne f. teves100% (7)

- Extending Our Assessments: Homework and TestingDocument22 pagesExtending Our Assessments: Homework and TestingRyan HoganNo ratings yet

- Teacher Self-Assessment of Current Practices in Math ClassDocument2 pagesTeacher Self-Assessment of Current Practices in Math ClassCristina Gabriela BrănoaeaNo ratings yet

- 4 Strategies of AfLDocument13 pages4 Strategies of AfLSadiaNo ratings yet

- Elements or Components of A Curriculum DesignDocument5 pagesElements or Components of A Curriculum DesignErrol CatimpoNo ratings yet

- Part III - Approaches in Teaching MathematicsDocument6 pagesPart III - Approaches in Teaching MathematicsCharis VasquezNo ratings yet

- Discovery Learning: Theresa Murphy, John Malloy, Sean O'BrienDocument32 pagesDiscovery Learning: Theresa Murphy, John Malloy, Sean O'BrienFauziaMaulidiastutiNo ratings yet

- Section 11 - Curriculum DeliveryDocument7 pagesSection 11 - Curriculum DeliveryCathlyn FloresNo ratings yet

- The 5es Instructional ModelDocument9 pagesThe 5es Instructional ModelRoselle BushNo ratings yet

- The Teaching of Science Module 5.Document116 pagesThe Teaching of Science Module 5.Neshema Faith EusebioNo ratings yet

- Problem Based Learning: I. DefinitionDocument6 pagesProblem Based Learning: I. DefinitionsadiaNo ratings yet

- Class Room MGNTDocument7 pagesClass Room MGNTVinusha KannanNo ratings yet

- Module 3 - UBDDocument12 pagesModule 3 - UBDJBM 0531100% (1)

- General Methods of Teaching (EDU301) : Question# 1 (A) Cooperative LearningDocument6 pagesGeneral Methods of Teaching (EDU301) : Question# 1 (A) Cooperative LearningsadiaNo ratings yet

- 7 Strategies To Assess Learning NeedsDocument11 pages7 Strategies To Assess Learning Needshammouam100% (1)

- Assessment Strategies (Classroom Assessment in Science)Document66 pagesAssessment Strategies (Classroom Assessment in Science)Rhendiel SanchezNo ratings yet

- Educ 5312Document5 pagesEduc 5312api-708665018No ratings yet

- 10 Innovative Formative Assessment Examples For TeachersDocument5 pages10 Innovative Formative Assessment Examples For TeachersDiana ArianaNo ratings yet

- Flipped Learningand ILDocument19 pagesFlipped Learningand ILEfecto McguffinNo ratings yet

- (Language Assessment II Practical Classroom Application) Topic 11Document28 pages(Language Assessment II Practical Classroom Application) Topic 11euisfrNo ratings yet

- Classroom Assessment ToolsDocument69 pagesClassroom Assessment ToolsSyeda Raffat HassanNo ratings yet

- (Prelim EDU105 Hazel v. Villanueva BSEScience) .Document4 pages(Prelim EDU105 Hazel v. Villanueva BSEScience) .JoelNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Basic Concepts of Assessment 1Document9 pagesModule 1 Basic Concepts of Assessment 1xandie wayawayNo ratings yet

- Interactive Assessments: Self-AssessmentDocument8 pagesInteractive Assessments: Self-AssessmentIoana ButiuNo ratings yet

- IBSEDocument4 pagesIBSEHunn MinNo ratings yet

- Teaching StrategiesDocument61 pagesTeaching StrategiesJorenal BenzonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document20 pagesChapter 2malouNo ratings yet

- K 8 (Tai Lieu)Document34 pagesK 8 (Tai Lieu)Trâm Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Untitled DesignDocument20 pagesUntitled DesignMelvin CastilloNo ratings yet

- Brookhart - Effective FeedbackDocument8 pagesBrookhart - Effective Feedbackapi-394711030No ratings yet

- Module 6Document165 pagesModule 6Er Lalit HimralNo ratings yet

- ED 106 Module (3rd-4th Week)Document6 pagesED 106 Module (3rd-4th Week)Mariza GiraoNo ratings yet

- FS 5 FileDocument25 pagesFS 5 FileJenni Alia33% (3)

- Bloom TaxonomyDocument7 pagesBloom TaxonomyBenjamin HaganNo ratings yet

- Formative Assessment StrategiesDocument5 pagesFormative Assessment StrategiesJonielNo ratings yet

- Using Reflection For AssessmentDocument2 pagesUsing Reflection For AssessmentTomika RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Formative Assessment Strategies For Gathering Evidence of Student LearningDocument7 pagesFormative Assessment Strategies For Gathering Evidence of Student LearningJohn Paul Viñas PhNo ratings yet

- American University of Science & Technology Faculty of Arts and Sciences Teaching Diploma ProgramDocument7 pagesAmerican University of Science & Technology Faculty of Arts and Sciences Teaching Diploma ProgramPascal Bou NajemNo ratings yet

- Adolescence A Crucial Transitional Stage in Human Life 2375 4494 1000e115Document2 pagesAdolescence A Crucial Transitional Stage in Human Life 2375 4494 1000e115dgsNo ratings yet

- Adolescenceinevolutionaryperspective 1994 ActaPaediatr PDFDocument9 pagesAdolescenceinevolutionaryperspective 1994 ActaPaediatr PDFdgsNo ratings yet

- Adolescence in Evolutionary Perspective: Acta Paediatrica (Oslo, Norway: 1992) - Supplement January 1995Document9 pagesAdolescence in Evolutionary Perspective: Acta Paediatrica (Oslo, Norway: 1992) - Supplement January 1995dgsNo ratings yet

- Is Adolescence A Sensitive Period For Sociocultural Processing?Document21 pagesIs Adolescence A Sensitive Period For Sociocultural Processing?dgs100% (1)

- Descriptive TextDocument1 pageDescriptive TextDharWin d'Wing-Wing d'AriestBoyzNo ratings yet

- Haffmans CPT: CO Purity TesterDocument2 pagesHaffmans CPT: CO Purity Testermouh niaNo ratings yet

- Immunization DR T V RaoDocument68 pagesImmunization DR T V Raotummalapalli venkateswara rao100% (1)

- Make The Most of A 2v1Document7 pagesMake The Most of A 2v1NAYIM OZNAIMNo ratings yet

- Camesa EMC CatalogDocument40 pagesCamesa EMC CatalogRoger DenegriNo ratings yet

- Navigating The Chemical MazeDocument11 pagesNavigating The Chemical MazeSreyashi MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Feasibility Study - WikipediaDocument7 pagesFeasibility Study - WikipediaPannad ChenNo ratings yet

- Greg Howe Improv TranscriptionDocument2 pagesGreg Howe Improv Transcriptionrian_defriNo ratings yet

- Layáhar Rozgar Yojana (JRY)Document2 pagesLayáhar Rozgar Yojana (JRY)Ajna FaizNo ratings yet

- LTE Acronym ListDocument9 pagesLTE Acronym Listmansour14No ratings yet

- Fortuna VS PeopleDocument1 pageFortuna VS PeopleMrln VloriaNo ratings yet

- Shoulder Pain and Disability Index Spadi1 PDFDocument2 pagesShoulder Pain and Disability Index Spadi1 PDFnurNo ratings yet

- Track ConsignmentDocument2 pagesTrack ConsignmentGD CONSULTANCYNo ratings yet

- Object Oriented Programming Lab FileDocument32 pagesObject Oriented Programming Lab FileRitika PooniaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - ErgonomicsDocument55 pagesChapter 6 - ErgonomicsDOUBLE TWINS ANo ratings yet

- Plumbing Technology-IntroductionDocument25 pagesPlumbing Technology-IntroductionMD. NAHID HOSSAINNo ratings yet

- Gujarat Technological University: (Civil)Document43 pagesGujarat Technological University: (Civil)Erik GarciaNo ratings yet

- Individual ReportDocument15 pagesIndividual ReportThanh HằngNo ratings yet

- Feldman Model of Criticism by Wendy RDocument2 pagesFeldman Model of Criticism by Wendy RHo Doris100% (1)

- Знімок екрана 2023-09-27 о 9.07.35 дпDocument89 pagesЗнімок екрана 2023-09-27 о 9.07.35 дпeleonorakovalcuk30No ratings yet

- P10319en2302 Anaesthesie WebDocument12 pagesP10319en2302 Anaesthesie WebRashad Biomedical EngineerNo ratings yet

- The Nursing ProcessDocument1 pageThe Nursing Processryan catbaganNo ratings yet

- Elements of A Short StoryDocument3 pagesElements of A Short StoryKans SisonNo ratings yet

- ENGL 158 - CV WritingDocument25 pagesENGL 158 - CV WritingSeyram AdomNo ratings yet

- Ps 2697warco WM 290V User Manual Parts List WWWDocument45 pagesPs 2697warco WM 290V User Manual Parts List WWWDaniel PichininNo ratings yet

- Performance Appraisal System of HDFC Life InsuranceDocument27 pagesPerformance Appraisal System of HDFC Life InsuranceShubham GhodapkarNo ratings yet

- Textile Internship at Alok IndustriesDocument8 pagesTextile Internship at Alok Industriessaroj anandNo ratings yet

- 01 Siain Enterprises Inc. vs. F.F. Cruz & Co., G.R. No. 146616, August 31, 2006Document6 pages01 Siain Enterprises Inc. vs. F.F. Cruz & Co., G.R. No. 146616, August 31, 2006Andrei Da JoseNo ratings yet