Ekky Imanjaya

Bina Nusantara University, Film, Faculty Member

- Cultural Theory, Media Studies, Film Studies, Popular Culture, Cinema, Asian Studies, and 50 moreFilm Analysis, Southeast Asian Studies, Culture Studies, Media History, Film Genre, Film, Pop Culture, Film Aesthetics, Indonesian Studies, Horror Film, Film Adaptation, Indonesia, National Cinemas, Film and History, Cult Movies, Southeast Asian history, Indonesian Culture, Exploitation Cinema, Indonesia (Area Studies), Movie, The Beatles, Indonesian Cinema, Cult Cinema, Teacher Movies in Pop Culture, Dracula, Frankenstein, Fantastic Literature and film, Cult Film, Underground Film, Cult Film, B-movies, Southeast Asian Cinema, Asian Cinema, John Fiske, Reformasi, Perfilman, New Order, Film History, Genre, Islam in Indonesia, Italian neorealist cinema, Andre Bazin, Audience and Reception Studies, Low-budget feature films, Science Fiction and Fantasy, Fandom, Fan Cultures, Horror, Cult television, Fan Communities, Cultural Studies, Social Media, and New Mediaedit

- Ekky Imanjaya Ph.D is a faculty member of Film Department, Bina Nusantara (Binus) University, in Jakarta. In 2018, He... moreEkky Imanjaya Ph.D is a faculty member of Film Department, Bina Nusantara (Binus) University, in Jakarta. In 2018, He finished his doctoral studies in Film Studies at University of East Anglia, United Kingdom. Previously, Ekky got his masters degree majoring Philosophy at Universitas Indonesia (2003) as well as in Film Studies at Universiteit van Amsterdam (2008).

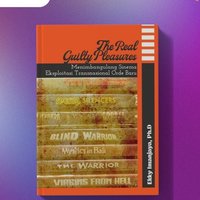

Ekky is also a film critic specializing in Indonesian cinema, and a board member of the Madani Film Festival and Jakarta Film Week. He is also a film critic and has published his articles in many popular magazines and newspapers as well as academic journals, including Cinemaya, Colloquy, Plaridel and Asian Cinema. He published some books regarding Indonesian films, pop culture, and Islamic culture issues, including "Mencari Film Madani: Sinema dan Dunia Islam" (2019), "Mujahid Film: Usmar Ismail" (2021), "99 Film Madani" (with Hikmat Darmawan, 2022), and "“The Real Guilty Pleasures: Menimbangulang Sinema Eksploitasi Transnasional Orde Baru”.

Ekky is currently the chairperson of Film Committee at Jakarta Arts Council (2021-2023).edit

Cinema, particularly documentary, can be a powerful vehicle for raising awareness of environmental sustainability. In the paper, the documentary film Pulau Plastik (Dandhy Laksono and Rahung Nasution 2021) is the subject of analysis. The... more

Cinema, particularly documentary, can be a powerful vehicle for raising awareness of environmental sustainability. In the paper, the documentary film Pulau Plastik (Dandhy Laksono and Rahung Nasution 2021) is the subject of analysis. The film has its premiere at the end of April 2021 in the cinema theatre in Jakarta, Yogyakarta, Surabaya and Denpasar and shows the plastic waste and its environmental damage. The documentary uses mise-en-scéne in its plot to evoke certain experience and emotion of the audience which we will examine its role and its psychological impact with the texts of the French philosopher Maurice Marleau-Ponty in the Philosophy of Embodiment, American experimental psychologist James Gibsons in Ecological Perception and American philosopher Sue Cataldi in Feelings, Depth and Flesh. The directors also use Cinéma Vérité Approach to strengthen the effect towards audience.

Research Interests:

As Parasite wins four Oscar awards at 2019 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, more film scholars and critics pay more attention to the South Korean film industry, particularly to the film director, Bong Joon-Ho.... more

As Parasite wins four Oscar awards at 2019 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, more film scholars and critics pay more attention to the South Korean film industry, particularly to the film director, Bong Joon-Ho. Regarding biospheric harmony, the director depicts “ecological monsters” in his works, namely toxic chemical waste, Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) and cruelty towards animals, and the frozen earth caused by global warming. By having a close reading and textual analysis on The Host (2006), Snowpiercer (2013), and Okja (2016), the research will focus on those films directed by Bong Joon-Ho, which represent the horrific environmental issues. Particularly, the authors will investigate how the three films depict the discourses of ecological problems. The results show how strong messages regarding ecological issues are represented in the three films, metaphorically and literally and become valuable lessons for environmentalists and film scholars/filmm...

Research Interests:

In this paper, the authors will try to better understand the phenomenon of gender swap film reboots by offering insight into why gender swap films are made in the first place , their purpose, and the role they play in Hollywood regarding... more

In this paper, the authors will try to better understand the phenomenon of gender swap film reboots by offering insight into why gender swap films are made in the first place , their purpose, and the role they play in Hollywood regarding gender equality and diversity. Since most gender swap reboots are adaptations from well-known franchises, it could give a new perspective and dimension to the story by telling it from the viewpoint of different genders. We assume that gender swap reboots were made to diversify movie casts by having female actors replace male actors and normalize the idea that women can do the same things as men. To prove our hypothesis, we will use a literature review and Netnography. In our study, we discovered that a handful of internet personalities and fans alike reject the idea of Ghostbusters (2016) because it has a different image from those they knew, which we argue is due to the gender swap factor itself. On the other hand, social activism also interplayed with gender swap phenomenon.

Research Interests:

by: Ephraim Ryan , Azwa Hanan, and Ekky Imanjaya In response to the pressing need to address climate change, there has been a growing interest in utilizing documentaries as a powerful tool for raising awareness and fostering social... more

by: Ephraim Ryan , Azwa Hanan, and Ekky Imanjaya

In response to the pressing need to address climate change, there has been a growing interest in utilizing documentaries as a powerful tool for raising awareness and fostering social change. This study adopts a comprehensive approach to analyze two influential environmental documentaries, namely Blackfish and An Inconvenient Truth. By employing a qualitative research methodology, specifically content

analysis, we aim to identify and examine the specific textual components and storytelling techniques employed in these films that contribute to their effectiveness in inspiring change. Our investigation focuses

on elucidating the narrative techniques, visual storytelling elements, and persuasive strategies utilized in the documentaries. By investigating these aspects, we seek to provide valuable insights and practical recommendations for filmmakers to create compelling and emotionally impactful films that can effectively promote social change.

In response to the pressing need to address climate change, there has been a growing interest in utilizing documentaries as a powerful tool for raising awareness and fostering social change. This study adopts a comprehensive approach to analyze two influential environmental documentaries, namely Blackfish and An Inconvenient Truth. By employing a qualitative research methodology, specifically content

analysis, we aim to identify and examine the specific textual components and storytelling techniques employed in these films that contribute to their effectiveness in inspiring change. Our investigation focuses

on elucidating the narrative techniques, visual storytelling elements, and persuasive strategies utilized in the documentaries. By investigating these aspects, we seek to provide valuable insights and practical recommendations for filmmakers to create compelling and emotionally impactful films that can effectively promote social change.

Research Interests:

The sophisticated technology-such as AI, robots, and other automation machines-can be a double-edged dagger. On the one hand, they can help humans and humanity to have a better and easier life. On the other hand, they can lead to... more

The sophisticated technology-such as AI, robots, and other automation machines-can be a double-edged dagger. On the one hand, they can help humans and humanity to have a better and easier life. On the other hand, they can lead to environmental problems-from plastic and electronic waste to obesityand, finally: Environmental destruction. In addition, a movie, including an animated film, can be a valuable and powerful vehicle as an educational tool to raise awareness of environmental issues as it can represent the negative effect of technology on the environment if people do not consider overcoming the ecological problems and maintaining biospheric harmony. This research will focus on the movie WALL-E (Andrew Stanton, 2008) and how it represents environmental damage and future life. By closely reading the film, the authors will analyse the struggle of life in the near future when the Earth is heavily polluted and full of trash and their attempt to return to sustainable well-being.

Research Interests:

In the age of social media and streaming platforms, the visuality of an idea has become much more important than before, including in the space of environmental activism. The representation of an ecoactivism idea campaigning for climate... more

In the age of social media and streaming platforms, the visuality of an idea has become much more important than before, including in the space of environmental activism. The representation of an ecoactivism idea campaigning for climate change, including the more radical practice of those activisms, is now communicated mainly not with written words but through the audio-visual medium of film or vlog to the audience. In the realm of cinema, films are worth analyzing regarding their representation of radical environmental activism Pom Poko (1994) directed by Isao Takahata, and First Reformed (2017) by Paul Schrader, because of their originality and nuanced representation of radical environmental activism. Through these films, we can see not only the surface representation of radical environmentalism but also the philosophy and reason behind it that usually has been overlooked. The authors chose both films to highlight that radical environmentalists' ideology and actions have been ...

Research Interests:

Disney characters always lead to gender development. Like a Disney princess who always depends on her prince to save her life. But now, the pattern is experiencing changes that occur in female characters. Women are no longer in a passive... more

Disney characters always lead to gender development. Like a Disney princess who always depends on her prince to save her life. But now, the pattern is experiencing changes that occur in female characters. Women are no longer in a passive position, but they begin to develop to be strong, challenging, and independent.

Through this paper, researchers will discuss several phases of the transition of female characters in Disney film production. By focusing on research questions, namely, how the nature of Disney women experiences a shift as a form of gender equality? To answer this question, researchers will use qualitative research methods that emphasize the depth of research and the results of the Disney film analysis.

Through this paper, researchers will discuss several phases of the transition of female characters in Disney film production. By focusing on research questions, namely, how the nature of Disney women experiences a shift as a form of gender equality? To answer this question, researchers will use qualitative research methods that emphasize the depth of research and the results of the Disney film analysis.

Research Interests:

Globally, the film industry decreased significantly due to COVID-19, starting in March 2020. Physical distancing, lockdown protocols, and other restricted regulations were applied. Vaccines were just founded and were not massively... more

Globally, the film industry decreased significantly due to COVID-19, starting in March 2020. Physical distancing, lockdown protocols, and other restricted regulations were applied. Vaccines were just founded and were not massively distributed. At that time, no official health protocols nor standard operating procedures regarding film production and movie theaters were applied in the "New Normal."The filmmaking businesses were threatened since film productions were restricted and movie theaters were closed down. The big dilemma occurred: which one was the priority: the safety of the crews and talents or the sustainability of national film industry? However, in 2021 there were some signs of progress. It started with Makmum 2 (December 2021), which obtained more than one million viewers. It is followed by Ku Kira Kau Rumah (February 2022) and KKN Desa Penari (April 2022), which reached 2,2 million and 3 million viewers, respectively. In prestigious film festivals, the movies such as Seperti Dendam, Rindu Harus Dibayar Tuntas, and Yuni won as the best pictures at Locarno Film Festival (August 2021) and Toronto Film Festival (September 2021), respectively. Many films showed cases in Festival Film Indonesia (December 2021). These have shown that the Indonesian film industry is becoming better commercially and critically. The paper investigates how the Indonesian filmmakers tried to adjust to the New Normal era from both creative works and business strategy perspectives. In particular, the authors will do the mapping on the best practices of health protocols applied in film production.

Research Interests:

Indonesia is rich in cultural diversity and traditions. Indonesia's unexpected cultural wealth ranges from tradition, art, tourism, and culinary. Indonesia is a country rich in culture. The relationship between Indonesian culture and... more

Indonesia is rich in cultural diversity and traditions. Indonesia's unexpected cultural wealth ranges from tradition, art, tourism, and culinary. Indonesia is a country rich in culture. The relationship between Indonesian culture and Indonesian Peranakan culture is also very close. The arrival of the Chinese from mainland China to Indonesia around the 14th or 15th century AD settled and married the locals, combining the socio-cultural and culinary diversity of the two nations. The culture born due to intercultural marriage is Indo-Chinese or Peranakan culture. This intangible heritage needs to be protected and preserved. Digital transformation in the manufacturing sector plays an essential role in the era of the industrial revolution 4.0. In 2018 the President of the Republic of Indonesia, Joko Widodo, launched a road map of Making Indonesia 4.0 with the aspiration to make Indonesia into the top 10 of the world economy by 2030. At the same time, Indonesia's s cultural and creative industries have developed, which play a significant role in promoting development. Indonesian economy. Indonesia supports creative innovation by deepening the concept that the cultural and creative industries encourage economic development. This paper raises the design of the Peranakan culture model to increase awareness of the Peranakan culture that can be sold in Indonesian tour packages. This model is expected to be developed to promote crossbreed tourism in other regions.

Research Interests:

Islamic films have found a devoted market in Indonesia. Commercial success will prolong the trend. Source: https://360info.org/islam-and-box-office-a-match-made-in-heaven/

Research Interests:

Animated films can be read as entertainment and a vehicle to reveal social, cultural, and environmental issues. One of the ecological problems is the bias of anthropocentric perspectives, which exclude and underestimate non-human agents... more

Animated films can be read as entertainment and a vehicle to reveal social, cultural, and environmental issues. One of the ecological problems is the bias of anthropocentric perspectives, which exclude and underestimate non-human agents such as animals from the consideration of their policymaking and other significant actions. In this worldview, instead of treating NHA as part of stakeholders, humans think they can exploit NHA and the environment for their benefit. This approach would threaten biospheric harmony. In this paper, Tarzan (1999) will be analyzed to determine whether the movie has an anthropocentric perspective or the other way around or both. The film is ideal since there are at least two kinds of human representations within the story. The first one is Tarzan, the main character, nurtured by and has a strong relationship with nature and oblivious about modern civilization until he met England explorers when he became an adult. On the other hand, Clayton is a hunter scout who disrespected the jungle and its dwellers. Textual analysis will be applied. A close reading of the movie will be undertaken to answer the research questions.

Research Interests:

Disney characters always lead to gender development. Like a Disney princess who always depends on her prince to save her life. But now, the pattern is experiencing changes that occur in female characters. Women are no longer in a passive... more

Disney characters always lead to gender development. Like a Disney princess who always depends on her prince to save her life. But now, the pattern is experiencing changes that occur in female characters. Women are no longer in a passive position, but they begin to develop to be strong, challenging, and independent. Through this paper, researchers will discuss several phases of the transition of female characters in Disney film production. By focusing on research questions, namely, how the nature of Disney women experiences a shift as a form of gender equality? To answer this question, researchers will use qualitative research methods that emphasize the depth of research and the results of the Disney film analysis.

ISSN: 2169-8767 (U.S. Library of Congress)

ISBN: 978-1-7923-9162-0 September 2022, Vol. 12 No. 6

ISSN: 2169-8767 (U.S. Library of Congress)

ISBN: 978-1-7923-9162-0 September 2022, Vol. 12 No. 6

Research Interests:

Globally, the film industry decreased significantly due to COVID-19, starting in March 2020. Physical distancing, lockdown protocols, and other restricted regulations were applied. Vaccines were just founded and were not massively... more

Globally, the film industry decreased significantly due to COVID-19, starting in March 2020. Physical distancing, lockdown protocols, and other restricted regulations were applied. Vaccines were just founded and were not massively distributed. At that time, no official health protocols nor standard operating procedures regarding film production and movie theaters were applied in the "New Normal."The filmmaking businesses were threatened since film productions were restricted and movie theaters were closed down. The big dilemma occurred: which one was the priority: the safety of the crews and talents or the sustainability of national film industry? However, in 2021 there were some signs of progress. It started with Makmum 2 (December 2021), which obtained more than one million viewers. It is followed by Ku Kira Kau Rumah (February 2022) and KKN Desa Penari (April 2022), which reached 2,2 million and 3 million viewers, respectively. In prestigious film festivals, the movies such as Seperti Dendam, Rindu Harus Dibayar Tuntas, and Yuni won as the best pictures at Locarno Film Festival (August 2021) and Toronto Film Festival (September 2021), respectively. Many films showed cases in Festival Film Indonesia (December 2021). These have shown that the Indonesian film industry is becoming better commercially and critically. The paper investigates how the Indonesian filmmakers tried to adjust to the New Normal era from both creative works and business strategy perspectives. In particular, the authors will do the mapping on the best practices of health protocols applied in film production.

Research Interests:

As stipulated in the Indonesian Labour Law, every worker/labour is entitled to have a work safety and health protection. The Labour Law no. 13 Year 2003, for instance, regulates the working hour and overtime, break, and leaves, and the... more

As stipulated in the Indonesian Labour Law, every worker/labour is entitled to have a work safety and health protection. The Labour Law no. 13 Year 2003, for instance, regulates the working hour and overtime, break, and leaves, and the rights of employees. in fact, the rights of workers in film industry are already ensured by the Government in the Law of Film Year 2009. However, to this day Indonesian film industry does not seem to officially implement these laws. There were several cases of Health, Safety, and Environment (HSE), which caused dead or fatal injuries to film workers, without applying the regulations mentioned above. Other HSE issues include the cases where only few film producers gave insurance to the film workers or apply proper risk assessment or provide first aid kits. By having in-depth interview with key persons of the field, such as the workers who are also assessors of Indonesian National Work Competency Standards (Standar Kompetensi Kerja Nasional Indonesia. SKKNI), as well as and film producers, this research aims to map out such issues and answering why and how the laws on work health and safety are not implemented in the Indonesian film industry. This research has resulted in the maps of problems, recommendations for the policymakers, film workers, and related institutes concerning HSE and the rights of film workers.

ISSN: 2169-8767 (U.S. Library of Congress)

ISBN: 978-1-7923-9162-0

September 2022, Vol. 12 No. 6

ISSN: 2169-8767 (U.S. Library of Congress)

ISBN: 978-1-7923-9162-0

September 2022, Vol. 12 No. 6

Research Interests:

Mengumpulkan tulisannya sejak 2008 hingga medio 2017-an, lahirlah 11 tulisan yang terhimpun dalam buku saku berjudul Mujahid Film. Buku tersebut merupakan kumpulan tulisan dari pengajar yang juga merupakan kritikus film, Ekky Imanjaya... more

Mengumpulkan tulisannya sejak 2008 hingga medio 2017-an, lahirlah 11 tulisan yang terhimpun dalam buku saku berjudul Mujahid Film. Buku tersebut merupakan kumpulan tulisan dari pengajar yang juga merupakan kritikus film, Ekky Imanjaya PhD. Isinya mengenai seluk-beluk Bapak Perfilman Indonesia, Usmar Ismail.Salah satu tujuan Ekky menerbitkan buku tersebut, menurutnya, bukan untuk mengultuskan Usmar, melainkan sebagai jalan untuk lebih mengenal sosok multidimensi Usmar Ismail.“Setiap tahun (Hari Film) dirayakan, seremonial, mentok cuma di (film) Tiga Dara, Lewat Djam Malam. Padahal, dia adalah sosok yang dinamis dan multidimensi. Tidak jadi sekadar monumen atau tugu peringatan. Karena itulah saya membahasnya di buku Mujahid Film,” kata Ekky saat berbincang dengan Media Indones...

Research Interests:

Indonesia is rich in cultural diversity and traditions. Indonesia's unexpected cultural wealth ranges from tradition, art, tourism, and culinary. Indonesia is a country rich in culture. The relationship between Indonesian culture and... more

Indonesia is rich in cultural diversity and traditions. Indonesia's unexpected cultural wealth ranges from tradition, art, tourism, and culinary. Indonesia is a country rich in culture. The relationship between Indonesian culture and Indonesian Peranakan culture is also very close. The arrival of the Chinese from mainland China to Indonesia around the 14th or 15th century AD settled and married the locals, combining the socio-cultural and culinary diversity of the two nations. The culture born due to intercultural marriage is Indo-Chinese or Peranakan culture. This intangible heritage needs to be protected and preserved. Digital transformation in the manufacturing sector plays an essential role in the era of the industrial revolution 4.0. In 2018 the President of the Republic of Indonesia, Joko Widodo, launched a road map of Making Indonesia 4.0 with the aspiration to make Indonesia into the top 10 of the world economy by 2030. At the same time, Indonesia's cultural and creative industries have developed, which play a significant role in promoting development. Indonesian economy. Indonesia supports creative innovation by deepening the concept that the cultural and creative industries encourage economic development. This paper raises the design of the Peranakan culture model to increase awareness of the Peranakan culture that can be sold in Indonesian tour packages. This model is expected to be developed to promote crossbreed tourism in other regions.

Research Interests:

Buku yang unik karena membahas dunia film di Indonesia, bukan dari sisi kreatif nya namun sisi ekonomi dan politiknya. Buku dengan tebal 374 halaman ini cocok untuk para orang yang ber-kecimplung di industri film khususnya sutradara dan... more

Buku yang unik karena membahas dunia film di Indonesia, bukan dari sisi kreatif nya namun sisi ekonomi dan politiknya. Buku dengan tebal 374 halaman ini cocok untuk para orang yang ber-kecimplung di industri film khususnya sutradara dan produser. Bahasan dan data yang disajikan di buku ini sangatlah kuat. Mampu memberikan sebuah alasan dan jawaban yang sering di pertanyakan oleh pecinta film di Indonesia. “Mengapa banyak film receh di Indonesia?”, jawabannya menurut buku ini pada tahun itu karena dalam perekonomian film di Indonesia tidak ada posisi tawar menawar oleh distributor-eksebitor karena resiko bisnis film yang tinggi. Sehingga beban untuk promosi kadang-kadang harus ditanggung oleh produser sendiri. Kalau diliat dari sisi kreatif, banyak sutradara di Indonesia yang muncul karena otodidak atau belajar sendiri

Research Interests:

142 hal.; 21 cm

Research Interests:

xiv, 84 hal. : ill.; 20 cm

Research Interests:

Do Commercialism and Islamic Law (Shariah) and Virtues become potential factors to lower the quality of so-called Indonesian ?Islamic Cinema??. Those factors seem to be embedded in most recent post- New Order Islamic films, and some film... more

Do Commercialism and Islamic Law (Shariah) and Virtues become potential factors to lower the quality of so-called Indonesian ?Islamic Cinema??. Those factors seem to be embedded in most recent post- New Order Islamic films, and some film critics highlight that most of the movies in this ?genre? are mediocre. In Salim Said?s point-of-view, the battle between commercial films versus idealist films is eternal. But how about the position of Islamic Law and virtues both in the content and (pre)production of idealist Islamic films: to endorse or to worsen the quality of the movie? On the other hand, there are some discourses from Dakwah activist claiming that both filmmaking process and the stories should obey fit with Fiqih and Shariah. For example, they try to find the way out the problem when there is a scene about husband and wife hugging, but in the real life they are not the real couple (thus, they are not allowed to do so). Ketika Cinta Bertasbih (When Love is praying) is another interesting case, while they create a TV show for casting the actors to be fitted with some Islamic values embodied in fiction characters.

Research Interests:

Mencari Film Madani: Sinema dan Dunia Islam merupakan kumpulan tulisan Ekky Imanjaya dengan tema khusus tentang seluk-beluk “film Islam”. Ekky Imanjaya sejak awal 2000-an berkarier sebagai wartawan dan kritikus film, lalu menekuni studi... more

Mencari Film Madani: Sinema dan Dunia Islam merupakan kumpulan tulisan Ekky Imanjaya dengan tema khusus tentang seluk-beluk “film Islam”. Ekky Imanjaya sejak awal 2000-an berkarier sebagai wartawan dan kritikus film, lalu menekuni studi film hingga meraih gelar master di Universitat van Amsterdam (Belanda) dan doctoral di University of East Anglia (Norwich, Inggris). Kumpulan ini menjadi unik sekaligus penting dalam konteks tumbuhnya genre film religious di dalam perfilman kita dari masa ke masa. Ekky menawarkan perspektif yang berpijak dari pengalamannya aktif di dunia dakwah semasa mudanya. Unduh e-book-nya: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1FRtP6s_YfFVx1ExyQoFW18K1NDq5qLus

Research Interests:

This articles explores how Indonesian film industry employed subversive and exploitative techniques to struggle against a dominant order. In particular, it discusses how the Indonesian exploitation films produced under the New Order... more

This articles explores how Indonesian film industry employed subversive and exploitative techniques to struggle against a dominant order. In particular, it discusses how the Indonesian exploitation films produced under the New Order Regime positioned their villains and criminals as symbols of the Suharto government, and how local and international fan activity and targeted DVD distribution has subsequently attained cult classification for many of these films. The films under consideration were produced and released in Indonesian cinemas during Suharto's New Order Regime (1966-1998). During this time nobody dared to voice their differences or criticize the government, without fear of being silenced or 'disappearing.' Nowadays the Indonesian people have more freedom to express their opinion although it may be different from, or even against, the government. The strongest period for this genre was approximately twenty years before the Reform Movement which led to the downfa...

Research Interests: Religion, Indonesian Culture, Popular Culture, Spirituality, Indonesian Studies, and 14 moreAudience and Reception Studies, Gender, Exploitation Cinema, Fan Cultures, Fandom, Cult television, Science Fiction and Fantasy, Cult Movies, Body Modification, Fanfiction, Fan Communities, Fan Charity, Horror, and Adaptation and Appropriation Theory

Die Reformasi Bewegung stürzte 1998 Präsident Suharto und brachte große soziale und politische Veränderungen. Aber wie waren Filme an diesen Wandel beteiligt und wie wirkten sich die gesellschaftspolitischen Veränderungen auf das... more

Die Reformasi Bewegung stürzte 1998 Präsident Suharto und brachte große soziale und politische Veränderungen. Aber wie waren Filme an diesen Wandel beteiligt und wie wirkten sich die gesellschaftspolitischen Veränderungen auf das indonesische Kino aus?

Research Interests:

Film archiving and local exploitation films, let alone the trashy film archive, are marginal in the discourses of film journalism, scholarship, policies, and criticism in Indonesia (Imanjaya, 2009c; Imanjaya, 2012a; Imanjaya, 2014).... more

Film archiving and local exploitation films, let alone the trashy film archive, are marginal in the discourses of film journalism, scholarship, policies, and criticism in Indonesia (Imanjaya, 2009c; Imanjaya, 2012a; Imanjaya, 2014). However, this paper will demonstrate the importance of Indonesian exploitation cinema, alternative film archives, and exploitation film preservation. It will focus on the output of Mondo Macabro, a transnational DVD label that consistently preserves world trashy films, including Indonesian films produced from the 1970s to the 1990s. By focusing on its DVD paratexts, that is, its DVD covers, special features, and online promotional materials, and applying the Chaperone archiving model also applied by Criterion Collection, this paper will also argue that Mondo Macabro gives trashy or cult films a new lease on life, and more importantly, treats them as collector’s items.

Research Interests:

Film-induced tourism becomes a new emerging issue in tourism and scholarly research for the last 10 years. London’s “Harry Potter” series and New Zealand’s “Lord of the Rings” are among the best practices of the trend. On the other hand,... more

Film-induced tourism becomes a new emerging issue in tourism and scholarly research for the last 10 years. London’s “Harry Potter” series and New Zealand’s “Lord of the Rings” are among the best practices of the trend. On the other hand, Indonesia is a country with many beautiful places to visit by both local and international tourists. The number of visitors increases significantly every year. However, there is no contribution from film industry, both from local or international production, related to this increasing numbers of tourists, not before national movie production “Laskar Pelangi, 2008” (Rainbow Troops, 2008) by Riri Riza, and international box office movie production “Eat, Pray Love, 2010”. The study research will discuss about film induced tourism issues in Indonesia, particularly on why and how the two films--so far, until recently, only those two films--became phenomenon in film tourism--and why other films did not.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

A List of books, papers, etc related to Indonesian Cinema written in English.

Research Interests:

Page 1. A ABOUT INDONESIAN FILM Buku ini membuktikan bahwa banyak aspek menarik dari perkembangan film Indonesia. Riri Riza, Sutradara Film Petualangan Sherina, Eliana Eliana, Gie. dan Untuk Rena Page 2. Page 3. ...

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Classic Indonesian exploitation films (originally produced, distributed, and exhibited in the New Order’s Indonesia from 1979 to 1995) are commonly negligible in both national and transnational cinema contexts, in the discourses of film... more

Classic Indonesian exploitation films (originally produced, distributed, and exhibited in the New Order’s Indonesia from 1979 to 1995) are commonly negligible in both national and transnational cinema contexts, in the discourses of film criticism, journalism, and studies. Nonetheless, in the 2000s, there has been a global interest in re-circulating and consuming this kind of films. The films are internationally considered as “cult movies” and celebrated by global fans. This thesis will focus on the cultural traffic of the films, from late 1970s to early 2010s, from Indonesia to other countries. By analyzing the global flows of the films I will argue that despite the marginal status of the films, classic Indonesian exploitation films become the center of a taste battle among a variety of interest groups and agencies. The process will include challenging the official history of Indonesian cinema by investigating the framework of cultural traffic as well as politics of taste, and highl...

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

During the dictatorship of Indonesia’s New Order regime (1966-1998), local exploitation films, layar tancap (traveling cinema) and its spectators were marginalised by legitimate culture. For example, layar tancap shows were framed to... more

During the dictatorship of Indonesia’s New Order regime (1966-1998), local exploitation films, layar tancap (traveling cinema) and its spectators were marginalised by legitimate culture. For example, layar tancap shows were framed to only operate in rural and suburban areas and were policed with several strict policies. Nonetheless, in this paper, I will demonstrate that layar tancap shows and their rural audiences are signs of cultural resistance which challenges legitimate culture, and that exploitation movies were a significant part of the process. By observing the New Order’s film policies as well as general and trade magazines, I will investigate why and how this kind of cinema operated as displays of classic Indonesian exploitation movies - the films the New Order was actually trying to eliminate - and how they generated a unique subculture of rural spectatorship. Here, I also want to highlight how various kinds of politics of taste - from the government to the rural spectators and the layar tancap entrepreneurs - interplayed in relation with local exploitation films, its rural audiences, and its culture of exhibition.

Research Interests:

Film archiving and local exploitation films, let alone the trashy film archive, are marginal in the discourses of film journalism, scholarship, policies, and criticism in Indonesia (Imanjaya, 2009c; Imanjaya, 2012a; Imanjaya, 2014).... more

Film archiving and local exploitation films, let alone the trashy film archive, are marginal in the discourses of film journalism, scholarship, policies, and criticism in Indonesia (Imanjaya, 2009c; Imanjaya, 2012a; Imanjaya, 2014). However, this paper will demonstrate the importance of Indonesian exploitation cinema, alternative film archives, and exploitation film preservation. It will focus on the output of Mondo Macabro, a transnational DVD label that consistently preserves world trashy films, including Indonesian films produced from the 1970s to the 1990s. By focusing on its DVD paratexts, that is, its DVD covers, special features, and online promotional materials, and applying the Chaperone archiving model also applied by Criterion Collection, this paper will also argue that Mondo Macabro gives trashy or cult films a new lease on life, and more importantly, treats them as collector’s items.

Research Interests:

Film-induced tourism becomes a new emerging issue in tourism and scholarly research for the last 10 years. London’s “Harry Potter” series and New Zealand’s “Lord of the Rings” are among the best practices of the trend. On the other hand,... more

Film-induced tourism becomes a new emerging issue in tourism and scholarly research for the last 10 years. London’s “Harry Potter” series and New Zealand’s “Lord of the Rings” are among the best practices of the trend. On the other hand, Indonesia is a country with many beautiful places to visit by both local and international tourists. The number of visitors increases significantly every year. However, there is no contribution from film industry, both from local or international production, related to this increasing numbers of tourists, not before national movie production “Laskar Pelangi, 2008” (Rainbow Troops, 2008) by Riri Riza, and international box office movie production “Eat, Pray Love, 2010”. The study research will discuss about film induced tourism issues in Indonesia, particularly on why and how the two films--so far, until recently, only those two films--became phenomenon in film tourism--and why other films did not.

Research Interests:

Banyak orang mengunggah berbagai materi ke meedia sosial yang berhubungan dengan memori kolektif. Pertanyaannya: Sejauh mana kita bisa menganggap Media-Baru, dalam hal ini Youtube dan Facebook, sebagai museum? Dan apa kendalanya? Penulis... more

Banyak orang mengunggah berbagai materi ke meedia sosial yang berhubungan dengan memori kolektif. Pertanyaannya: Sejauh mana kita bisa menganggap Media-Baru, dalam hal ini Youtube dan Facebook, sebagai museum? Dan apa kendalanya?

Penulis membatasi masalah pada memori kolektif kaum urban atas budaya pop yang pernah mereka alami, khususnya materi audio visual. Dan umumnya sumber berasal dari cuplikan TVRI atau film-film bioskop. Dan fokus paper ini adalah Youtube dan

Facebook dengan materi audio visual karya anak bangsa sendiri.

Ini adalah paper yang saya presentasikan di Universitas Mercu Buana, 10 Mei 2011. Versi cetaknya dimuat dalam buku " The Reposition of Communication in the Dynamic Convergence: Reposisi Komunikasi dalam Dinamika Konvergensi" (Universitas Mercu Buana, Januari 2012).

Link: http://fikom.mercubuana.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/SemuaTerekamTakPernahMati_EkkyImanjaya.pdf

Penulis membatasi masalah pada memori kolektif kaum urban atas budaya pop yang pernah mereka alami, khususnya materi audio visual. Dan umumnya sumber berasal dari cuplikan TVRI atau film-film bioskop. Dan fokus paper ini adalah Youtube dan

Facebook dengan materi audio visual karya anak bangsa sendiri.

Ini adalah paper yang saya presentasikan di Universitas Mercu Buana, 10 Mei 2011. Versi cetaknya dimuat dalam buku " The Reposition of Communication in the Dynamic Convergence: Reposisi Komunikasi dalam Dinamika Konvergensi" (Universitas Mercu Buana, Januari 2012).

Link: http://fikom.mercubuana.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/SemuaTerekamTakPernahMati_EkkyImanjaya.pdf

Research Interests:

An Introduction from guest editor. "The Bad, The Worse, and The Worst: The Significance of Indonesian Cult, Exploitation, and B Movies" Plaridel Journal, Special Issue, Vol 11, Issue No. 2, 2014. Guest Editor: Ekky Imanjaya (PhD... more

An Introduction from guest editor.

"The Bad, The Worse, and The Worst: The Significance of Indonesian Cult, Exploitation, and B Movies"

Plaridel Journal, Special Issue, Vol 11, Issue No. 2, 2014.

Guest Editor: Ekky Imanjaya

(PhD Candidate, University of East Anglia, UK;

faculty member, school of Film, Binus International, Bina Nusantara University, Indonesia)

Front cover: http://www.plarideljournal.org/author/ekky-imanjaya

Table of Content: http://plarideljournal.org/article/table-contents-0

1. A Note from the Editor : The Significance of Indonesian Cult, Exploitation, and B-Movies

By Ekky Imanjaya (guest editor; PhD Candidate, University of East Anglia; Lecturer, Bina Nusantara University) http://plarideljournal.org/article/significance-indonesian-cult-exploitation-and-b-movies

2. Exploiting Indonesia: From “Primitives” to “Outraged Fugitives”

By Thomas Barker (Assistant Professor of Film and Television, the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus)

http://plarideljournal.org/article/exploiting-indonesia-primitives-outraged-fugitives

3. The Raiding Dutchmen: Colonial stereotypes, identity and Islam in Indonesian B-movies

By Eric Sasono (postgraduate student at Film Studies Department, King’s College, London)

http://plarideljournal.org/article/raiding-dutchmen-colonial-stereotypes-identity-and-islam-indonesian-b-movies

4. The Earth is Getting Hotter: Urban Inferno and Outsider Women’s Collectives in Bumi Makin Panas

By Dag Yngvesson (PhD Candidate, University of Minnesota)

http://plarideljournal.org/article/earth-getting-hotter-urban-inferno-and-outsider-women%E2%80%99s-collectives-bumi-makin-panas

5. Challenging New Order’s Gender Ideology in Benyamin Sueb’s Betty Bencong Slebor: A Queer Reading

By Maimunah Munir (doctoral program student , South East Asian Studies, the University of Sydney, Australia)

http://plarideljournal.org/article/challenging-new-order%E2%80%99s-gender-ideology-benyamin-sueb%E2%80%99s-betty-bencong-slebor-queer-reading-0

6. Genre versus Local Specificity: Configuring Rangda and Durga in Balinese and Bengali Films

By Makbul Mubarak (Lecturer, Universitas Multimedia Nusantara)—coming soon.

Abstract:

http://www.plarideljournal.org/article/genre-versus-local-specificity-configuring-rangda-and-durga-balinese-and-bengali-films

7. Beneath Still Waters: Brian Yuzna and the Transnational Indonesian Terror Text

By Xavier Mendik (Associate Head in the School of Art, Media and Design at the University of Brighton, Director of Cine-Excess International Film Festival

http://plarideljournal.org/article/beneath-still-waters-brian-yuzna%E2%80%99s-ritual-return-indonesian-cinema

Documents:

1. When East Meets West: American and Chinese influences on early Indonesian Action cinema

The List of Filmography of Early Indonesian Action Movies (1926-1941)

compiled by by Bastian Meiresonne (Asian movies specialist, director of Garuda Power: The Spirit Within)

http://plarideljournal.org/article/when-east-meets-west-american-and-chinese-influences-early-indonesian-action-cinema-list

2. On Lady Terminator

Interview with Barbara Anne Constable

By Andrew Leavold (Ph.D. candidate, Griffith University, director of “The Search for Weng Weng”)

http://plarideljournal.org/article/lady-terminator-interview-barbara-anne-constable

3. Beneath Still Waters: The Brian Yuzna Interview http://plarideljournal.org/article/beneath-still-waters-brian-yuzna-interview

By Xavier Mendik

4. Scripting an Indonesian Monster: The John Penney Interview: http://plarideljournal.org/article/scripting-indonesian-monster-john-penney-interview

"The Bad, The Worse, and The Worst: The Significance of Indonesian Cult, Exploitation, and B Movies"

Plaridel Journal, Special Issue, Vol 11, Issue No. 2, 2014.

Guest Editor: Ekky Imanjaya

(PhD Candidate, University of East Anglia, UK;

faculty member, school of Film, Binus International, Bina Nusantara University, Indonesia)

Front cover: http://www.plarideljournal.org/author/ekky-imanjaya

Table of Content: http://plarideljournal.org/article/table-contents-0

1. A Note from the Editor : The Significance of Indonesian Cult, Exploitation, and B-Movies

By Ekky Imanjaya (guest editor; PhD Candidate, University of East Anglia; Lecturer, Bina Nusantara University) http://plarideljournal.org/article/significance-indonesian-cult-exploitation-and-b-movies

2. Exploiting Indonesia: From “Primitives” to “Outraged Fugitives”

By Thomas Barker (Assistant Professor of Film and Television, the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus)

http://plarideljournal.org/article/exploiting-indonesia-primitives-outraged-fugitives

3. The Raiding Dutchmen: Colonial stereotypes, identity and Islam in Indonesian B-movies

By Eric Sasono (postgraduate student at Film Studies Department, King’s College, London)

http://plarideljournal.org/article/raiding-dutchmen-colonial-stereotypes-identity-and-islam-indonesian-b-movies

4. The Earth is Getting Hotter: Urban Inferno and Outsider Women’s Collectives in Bumi Makin Panas

By Dag Yngvesson (PhD Candidate, University of Minnesota)

http://plarideljournal.org/article/earth-getting-hotter-urban-inferno-and-outsider-women%E2%80%99s-collectives-bumi-makin-panas

5. Challenging New Order’s Gender Ideology in Benyamin Sueb’s Betty Bencong Slebor: A Queer Reading

By Maimunah Munir (doctoral program student , South East Asian Studies, the University of Sydney, Australia)

http://plarideljournal.org/article/challenging-new-order%E2%80%99s-gender-ideology-benyamin-sueb%E2%80%99s-betty-bencong-slebor-queer-reading-0

6. Genre versus Local Specificity: Configuring Rangda and Durga in Balinese and Bengali Films

By Makbul Mubarak (Lecturer, Universitas Multimedia Nusantara)—coming soon.

Abstract:

http://www.plarideljournal.org/article/genre-versus-local-specificity-configuring-rangda-and-durga-balinese-and-bengali-films

7. Beneath Still Waters: Brian Yuzna and the Transnational Indonesian Terror Text

By Xavier Mendik (Associate Head in the School of Art, Media and Design at the University of Brighton, Director of Cine-Excess International Film Festival

http://plarideljournal.org/article/beneath-still-waters-brian-yuzna%E2%80%99s-ritual-return-indonesian-cinema

Documents:

1. When East Meets West: American and Chinese influences on early Indonesian Action cinema

The List of Filmography of Early Indonesian Action Movies (1926-1941)

compiled by by Bastian Meiresonne (Asian movies specialist, director of Garuda Power: The Spirit Within)

http://plarideljournal.org/article/when-east-meets-west-american-and-chinese-influences-early-indonesian-action-cinema-list

2. On Lady Terminator

Interview with Barbara Anne Constable

By Andrew Leavold (Ph.D. candidate, Griffith University, director of “The Search for Weng Weng”)

http://plarideljournal.org/article/lady-terminator-interview-barbara-anne-constable

3. Beneath Still Waters: The Brian Yuzna Interview http://plarideljournal.org/article/beneath-still-waters-brian-yuzna-interview

By Xavier Mendik

4. Scripting an Indonesian Monster: The John Penney Interview: http://plarideljournal.org/article/scripting-indonesian-monster-john-penney-interview

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Usmar Ismail, considered as the Father of Indonesian Cinema, made films in what was then called Malaya. The titles are Korban Fitnah / Defamation Victim, produced in 1959 by Cathay-Keris Films in Singapore, and Bayangan di Waktu Fajar /... more

Usmar Ismail, considered as the Father of Indonesian Cinema, made films in what was then called Malaya. The titles are Korban Fitnah / Defamation Victim, produced in 1959 by Cathay-Keris Films in Singapore, and Bayangan di Waktu Fajar / Shadow at Dawn, released in 1963 with Cathay-Keris co-producing with PERFINI, Usmar’s own film production company. In Malaysia, those two films are available in VCD format. But in Indonesia, the films are forgotten and the only access to watch them is to go to Sinematek Indonesia. Those two films are cases of "Orphan Films".

Research Interests:

Indonesian film posters were accused as plagiarism by common people. However, academically speaking, it needs deeper skills and knowledge to prove acts of plagiarism. This paper will discuss the issues around Indonesian film posters and... more

Indonesian film posters were accused as plagiarism by common people. However, academically speaking, it needs deeper skills and knowledge to prove acts of plagiarism. This paper will discuss the issues around Indonesian film posters and plagiarism, including the possibility of citing in graphic design. The research will treat film posters not only as marketing tools to promote the movies, as many people consider, but also as graphic design materials. Some terms such as appropriation, homage, and pastiche will be discussed to analyze the phenomenon.

Research Interests:

Many Indonesian movie-goers think that Indonesian films must be avoided because of the bad quality and just wasting time and money.

Why do the movie-goers become traumatic? How to mend these mocking spectators?

Why do the movie-goers become traumatic? How to mend these mocking spectators?

Research Interests:

Ekky Imanjaya's anthology of essays, academic papers, and popular writings on Usmar Ismail (Considered as the Father of Indonesian Cinema), launched as part of the celebration of the 100th Years of Usmar Ismail (20 March 1921-2021) Some... more

Ekky Imanjaya's anthology of essays, academic papers, and popular writings on Usmar Ismail (Considered as the Father of Indonesian Cinema), launched as part of the celebration of the 100th Years of Usmar Ismail (20 March 1921-2021)

Some articles are in Indonesian, some are in English.

Chapters:

Usmar Ismail: Sebuah Perkenalan

1. Introduction to Usmar Ismail

2. Sang Mujahid Seni Indonesia

Ulasan Film

3. Tiga Menguak Usmar

4. Tukang Obat dan Kampanye Caleg di Sinema Kita,

5. Harimau Tjampa: Kelindan Pencak Silat dengan Islam

Lesbumi, Sensor, Politik

6. Sensor dalam Film

7. Lesbumi, Dari Jembatan Ulama-Seniman

Warisan, Restorasi, dan Transnasionalisme

8. Restoration of Lewat Djam Malam: The Importance, the Process, and the Obstacles

9. Two Orphan Films by Usmar Ismail

10. Indonesia’s Three Sisters Movies, Cultural Importance, and the Legacy of Challenging the Society

11. Revisiting Italian Neorealism: Its influence toward Indonesia and Asian Cinema or There’s No Such Thing Like Pure Neorealist Films

It can be purchased on

(1) Shopee: https://shopee.co.id/Mujahid-Film-Usmar-Ismail-i.134996611.8029183334 Rp 65.000,- (pre-order, printed)

(2) Storial.co https://www.storial.co/book/mujahid-film-usmar-ismail (e-book, full version Rp 55.000,- can be purchased per articles)

Or, simply type “Usmar Ismail” at di Shopee.co.id or Storial.co

#100TahunUsmarIsmail #BulanFilmNasional

Some articles are in Indonesian, some are in English.

Chapters:

Usmar Ismail: Sebuah Perkenalan

1. Introduction to Usmar Ismail

2. Sang Mujahid Seni Indonesia

Ulasan Film

3. Tiga Menguak Usmar

4. Tukang Obat dan Kampanye Caleg di Sinema Kita,

5. Harimau Tjampa: Kelindan Pencak Silat dengan Islam

Lesbumi, Sensor, Politik

6. Sensor dalam Film

7. Lesbumi, Dari Jembatan Ulama-Seniman

Warisan, Restorasi, dan Transnasionalisme

8. Restoration of Lewat Djam Malam: The Importance, the Process, and the Obstacles

9. Two Orphan Films by Usmar Ismail

10. Indonesia’s Three Sisters Movies, Cultural Importance, and the Legacy of Challenging the Society

11. Revisiting Italian Neorealism: Its influence toward Indonesia and Asian Cinema or There’s No Such Thing Like Pure Neorealist Films

It can be purchased on

(1) Shopee: https://shopee.co.id/Mujahid-Film-Usmar-Ismail-i.134996611.8029183334 Rp 65.000,- (pre-order, printed)

(2) Storial.co https://www.storial.co/book/mujahid-film-usmar-ismail (e-book, full version Rp 55.000,- can be purchased per articles)

Or, simply type “Usmar Ismail” at di Shopee.co.id or Storial.co

#100TahunUsmarIsmail #BulanFilmNasional

Research Interests:

Kumpulan esai, ulasan, laporan festival film, wawancara, dan trivia. Lebih dari 1600 halaman. Unduh gratis: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1YiMAx-fjtRZo02cUhJd0ygaZvPfJlAsA Seri Wacana Sinema. Penerbit: Komite Film Dewan... more

Kumpulan esai, ulasan, laporan festival film, wawancara, dan trivia.

Lebih dari 1600 halaman.

Unduh gratis: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1YiMAx-fjtRZo02cUhJd0ygaZvPfJlAsA

Seri Wacana Sinema.

Penerbit: Komite Film Dewan Kesenian Jakarta, 2019

Direktur Penerbitan : Hikmat Darmawan

Editor Seri : Ekky Imanjaya

Editor:

Ekky Imanjaya

Hikmat Darmawan

Rumah Film:

Asmayani Kusrini, Ekky Imanjaya, Eric Sasono, Hikmat Darmawan, Ifan Ismail, Krisnadi Yuliawan

Kontributor:

Bobby Batara, Donny Anggoro, Hassan Abdul Muthalib, Intan Paramaditha, Veronika Kusumaryati, Ade Irwansyah, Grace Samboh, Homer Harianja, Windu Jusuf,

Penyelaras : Ignatius Haryanto

Desain dan Tata Letak : Ardi Yunanto & Andang Kelana

Lebih dari 1600 halaman.

Unduh gratis: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1YiMAx-fjtRZo02cUhJd0ygaZvPfJlAsA

Seri Wacana Sinema.

Penerbit: Komite Film Dewan Kesenian Jakarta, 2019

Direktur Penerbitan : Hikmat Darmawan

Editor Seri : Ekky Imanjaya

Editor:

Ekky Imanjaya

Hikmat Darmawan

Rumah Film:

Asmayani Kusrini, Ekky Imanjaya, Eric Sasono, Hikmat Darmawan, Ifan Ismail, Krisnadi Yuliawan

Kontributor:

Bobby Batara, Donny Anggoro, Hassan Abdul Muthalib, Intan Paramaditha, Veronika Kusumaryati, Ade Irwansyah, Grace Samboh, Homer Harianja, Windu Jusuf,

Penyelaras : Ignatius Haryanto

Desain dan Tata Letak : Ardi Yunanto & Andang Kelana

Research Interests:

Mencari Film Madani: Sinema dan Dunia Islam merupakan kumpulan tulisan Ekky Imanjaya dengan tema khusus tentang seluk-beluk “film Islam”. Ekky Imanjaya sejak awal 2000-an berkarier sebagai wartawan dan kritikus film, lalu menekuni studi... more

Mencari Film Madani: Sinema dan Dunia Islam merupakan kumpulan tulisan Ekky Imanjaya dengan tema khusus tentang seluk-beluk “film Islam”. Ekky Imanjaya sejak awal 2000-an berkarier sebagai wartawan dan kritikus film, lalu menekuni studi film hingga meraih gelar master di Universitat van Amsterdam (Belanda) dan doctoral di University of East Anglia (Norwich, Inggris). Kumpulan ini menjadi unik sekaligus penting dalam konteks tumbuhnya genre film religious di dalam perfilman kita dari masa ke masa. Ekky menawarkan perspektif yang berpijak dari pengalamannya aktif di dunia dakwah semasa mudanya.

Unduh e-book-nya: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1FRtP6s_YfFVx1ExyQoFW18K1NDq5qLus

Unduh e-book-nya: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1FRtP6s_YfFVx1ExyQoFW18K1NDq5qLus

Research Interests:

How Eliana, Eliana and Rindu Kami pada-Mu), as case studies of post-Reform Indonesian films, represent social issues in Jakarta in a (neo)-realistic way? This thesis focuses on the representation of social issues in the city of Jakarta,... more

How Eliana, Eliana and Rindu Kami pada-Mu), as case studies of post-Reform Indonesian films, represent social issues in Jakarta in a (neo)-realistic way? This thesis focuses on the representation of social issues in the city of Jakarta, such as gender issues, poverty and the problems of urban life, as well as the physical landscape and mental landscape of Jakarta, and the connection between representation theory and realism approach in filmmaking.

Research Interests:

"Syari'ati tidak pernah menggagas pemikirannya tentang etika secara utuh dalam bentuk tulisan atau ceramah. Tetapi berbagai kritiknya terhadap filsafat Barat, termasuk etika, secara implisit mengandung pemikirannya tentang etika. Beberapa... more

"Syari'ati tidak pernah menggagas pemikirannya tentang etika secara utuh dalam bentuk tulisan atau ceramah. Tetapi berbagai kritiknya terhadap filsafat Barat, termasuk etika, secara implisit mengandung pemikirannya tentang etika. Beberapa pemikirannya, yang sebagian besar digunakan secara praksis untuk menggerakkan revolusi di Iran, juga mengandung sebuah implikasi tindakan etis tertentu. Pemikiran filosofisnya di bidang ontologi dan meteafisika sebenarnva juga mengandung ajarannya tentang etika. Bagaimana etika menurut Syari'ati? Bagi Syari'ati, manusia adalah makhluk dua dimensi, yaitu unsur Roh Tuhan dan Tanah Lumpur. Keduanya saling bertempur. Roh Tuhan ingin selalu menjadi insan (becoming) menuju Tuhan, yaitu ""berakhlak seperti Akhlak Tuhan"". Tetapi unsur`fanah Lumpur selalu menghalanginya. Pertempuran di dalam diri manusia ini selalu terjadi, dan jika Roh Tuhan menang, mala manusia menjadi ""manusia ideal"". Tanah Lumpur ini adalah penjara Ego, yaitu penjara psikologis yang menghalangi insan menuju Tuhan. Tuhan adalah tujuan akhir manuia, yang selalu berubah dan bergerak dinamis. Pada akhirnya, manusia tidak akan pernah menuju Tuhan, tetapi selalu menghampirinya. Proses terus menueru rnr menghasilkan tindakan moral (akhlak) yang menial tindakan moralk Tuhan. Intl dari etika Syari'ati adalah upaya humanisasi, yaitu menjadikan manusia menjadi ""manusia yang sesungguhnya"" (insan) Intl dari humanisasi ini adalah liberalisasi dan transendensi

Research Interests:

Historical approach on Indonesian film industry from 1926 to present.

Research Interests:

Video Presentation: https://kafein.or.id/en/history-panel/ Mainstream perspectives regarding gender issues, both in popular and scholarly works, underline that generally films in Indonesian New Order (1966-1998) apply State Ibusim... more

Video Presentation: https://kafein.or.id/en/history-panel/

Mainstream perspectives regarding gender issues, both in popular and scholarly works, underline that generally films in Indonesian New Order (1966-1998) apply State Ibusim theories. On and off-screen, women were marginalized and represented as weak, silent, negative, housewificationed, dan domestificationed. State Ibuism theory was coined by Julia Suryakusuma, formulated based from PKK program (Pembinaan Kesejahteraan Keluarga (Family Welfare Movement), “azas kekeluargaan” (Family Principle), amd and Dharma Wanita (official organization for the wives of civil servants), which were officially issued in 1978. The theory highlight the official attempt of domistification of Indonesian women during New Order era.

However, Lisa (M Syariefuddin A, 1971), produced 7 years before the programs, is anomalous one. I argue that the film can be read as the window opportunity for producing the progressive film culture. I will answer how different the film with State Ibuism theory by undertaking textual analysis or a close reading of the film. And I will answer why it is different by undertaking New Cinema History approach and highlighting the paradoxes of New Order’s policies.

Presented at “Women in Indonesian Film and Cinema” Conference, July-August 2020, An INTERNATIONAL VIRTUAL CONFERENCE, held by UNESCO, BPI, and Kafein.

Mainstream perspectives regarding gender issues, both in popular and scholarly works, underline that generally films in Indonesian New Order (1966-1998) apply State Ibusim theories. On and off-screen, women were marginalized and represented as weak, silent, negative, housewificationed, dan domestificationed. State Ibuism theory was coined by Julia Suryakusuma, formulated based from PKK program (Pembinaan Kesejahteraan Keluarga (Family Welfare Movement), “azas kekeluargaan” (Family Principle), amd and Dharma Wanita (official organization for the wives of civil servants), which were officially issued in 1978. The theory highlight the official attempt of domistification of Indonesian women during New Order era.

However, Lisa (M Syariefuddin A, 1971), produced 7 years before the programs, is anomalous one. I argue that the film can be read as the window opportunity for producing the progressive film culture. I will answer how different the film with State Ibuism theory by undertaking textual analysis or a close reading of the film. And I will answer why it is different by undertaking New Cinema History approach and highlighting the paradoxes of New Order’s policies.

Presented at “Women in Indonesian Film and Cinema” Conference, July-August 2020, An INTERNATIONAL VIRTUAL CONFERENCE, held by UNESCO, BPI, and Kafein.

Research Interests:

For years, textual analysis or ontological approaches is a common thing among scholars and critics in the context of Indonesian cinema studies. Currently, there is an emerging trend of research where more scholars apply... more

For years, textual analysis or ontological approaches is a common thing among scholars and critics in the context of Indonesian cinema studies. Currently, there is an emerging trend of research where more scholars apply phenomenological or sociological approaches to research Indonesian cinema. Within this approaches, extrinsic elements are investigated and archive-led research is inevitable. In my case, I analyzed many archives in order to argue that classic Indonesian exploitation films (originally produced and circulated between 1979 and 1995 under the dictatorship of New Order) are important and the films became both the significant arenas and the objects of politics of taste involving several agencies like the State and its cultural elites, local film producers, local film distributors/exhibitors, local audiences, transnational distributors, and global fans.

Therefore, my research is in line with “New Cinema History”, as Maltby puts it, “to consider their circulation and consumption, and to examine the cinema as a site of social and cultural exchange” (Maltby, 2011, 1). New Cinema History approaches undertake “empirical investigation and inquiry”, which is “analysis of primary sources relating to the production and reception of feature films” (Chapman, Glancy, Harper 2009, 1).

Within this spirit, the film historians basically undertake historical investigation by analyzing primary sources, both filmic (the film itself), and nonfilmic (such as trade papers, publicity materials, reviews, and fans texts) (Chapman, Glancy, Harper 2007, 3).

The paper will elaborate how and why I collected, selected, and analyzed original printed documents such as magazines, newspapers, official documents (for instance, ministerial and presidential decrees and film censorship policies), trade magazines (including in-house and internal magazines published by particular film organizations), and festival film catalogs and booklets. I will focus on 3 institutions, namely Sinematek Indonesia (Indonesia’s film archive), Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia (National Library of Indonesia) and Perpustakaan Umum Pemerintah Daerah Jakarta (Public Library of Jakarta Province).

‘Archives, Activism, Aesthetics in Southeast Asian Cinemas’ Symposium, Glasgow, 16-17 March 2018

Therefore, my research is in line with “New Cinema History”, as Maltby puts it, “to consider their circulation and consumption, and to examine the cinema as a site of social and cultural exchange” (Maltby, 2011, 1). New Cinema History approaches undertake “empirical investigation and inquiry”, which is “analysis of primary sources relating to the production and reception of feature films” (Chapman, Glancy, Harper 2009, 1).

Within this spirit, the film historians basically undertake historical investigation by analyzing primary sources, both filmic (the film itself), and nonfilmic (such as trade papers, publicity materials, reviews, and fans texts) (Chapman, Glancy, Harper 2007, 3).

The paper will elaborate how and why I collected, selected, and analyzed original printed documents such as magazines, newspapers, official documents (for instance, ministerial and presidential decrees and film censorship policies), trade magazines (including in-house and internal magazines published by particular film organizations), and festival film catalogs and booklets. I will focus on 3 institutions, namely Sinematek Indonesia (Indonesia’s film archive), Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia (National Library of Indonesia) and Perpustakaan Umum Pemerintah Daerah Jakarta (Public Library of Jakarta Province).

‘Archives, Activism, Aesthetics in Southeast Asian Cinemas’ Symposium, Glasgow, 16-17 March 2018

Research Interests:

As non-state agents, cultural elites along with the government played important roles in cultural history of Indonesia in New Order period (1966-1998). Krishna Sen overviews history of Indonesian Cinema in New Order in one sentence: “The... more

As non-state agents, cultural elites along with the government played important roles in cultural history of Indonesia in New Order period (1966-1998). Krishna Sen overviews history of Indonesian Cinema in New Order in one sentence: “The New Order inherited a cinema that expressed a highly individualist and elitist approach to society” (Sen 1994, 94). In the Indonesian context, culture elites are a group of prominent figures who share the same ideology and mostly belong to nationalist wing who try to play a role as, In Toynbee’s term,

a group of “creative minority”. Krishna Sen describes them as “the tiny urban, educated, national political elites, which since independence had been bound by personal ties that bridged ‘conflict of interest’ and ideology” (Sen 1994, 27). The phenomenon can be read in

articles written by most prominent film critics, journalists, historians, and academia such as Asrul Sani (poet, cultural thinker, prominent writer, award-winning scriptwriter, director), Rosihan Anwar (senior journalist), Sumardjono (filmmaker), Misbach Jusa Biran (film historian, founder of Sinematek Indonesia, filmmaker), and Salim Said (film scholar). They

also played roles in some film institutions and organizations, such as Festival Film Indonesia, censorship board, National Film Council (Dewan Film Nasional). They wanted to frame Indonesian film to fit in the concept of film nasional (national film), where the goals were to “search Indonesian faces on screen” (1978) and should be “with cultural and

educational purposes” (Film Kultural Edukatif, 1982-1983) (2010).

In this paper, I will elaborate why and how Indonesian cultural elites in New Order era have tried to exclude local exploitation films from the discourses of concept and official history of national cinema and national film cultures, and tried to negotiate with various kinds of politics of tastes.

By investigating archives such as film policies and media clippings, I will underline the taste battle between the government and cultural elites and other stakeholders, namely local film producers-distributors-exhibitors (including Layar Tancap/traveling cinema companies), and domestic mainstream audience, as well as international distributors.

a group of “creative minority”. Krishna Sen describes them as “the tiny urban, educated, national political elites, which since independence had been bound by personal ties that bridged ‘conflict of interest’ and ideology” (Sen 1994, 27). The phenomenon can be read in

articles written by most prominent film critics, journalists, historians, and academia such as Asrul Sani (poet, cultural thinker, prominent writer, award-winning scriptwriter, director), Rosihan Anwar (senior journalist), Sumardjono (filmmaker), Misbach Jusa Biran (film historian, founder of Sinematek Indonesia, filmmaker), and Salim Said (film scholar). They

also played roles in some film institutions and organizations, such as Festival Film Indonesia, censorship board, National Film Council (Dewan Film Nasional). They wanted to frame Indonesian film to fit in the concept of film nasional (national film), where the goals were to “search Indonesian faces on screen” (1978) and should be “with cultural and

educational purposes” (Film Kultural Edukatif, 1982-1983) (2010).

In this paper, I will elaborate why and how Indonesian cultural elites in New Order era have tried to exclude local exploitation films from the discourses of concept and official history of national cinema and national film cultures, and tried to negotiate with various kinds of politics of tastes.

By investigating archives such as film policies and media clippings, I will underline the taste battle between the government and cultural elites and other stakeholders, namely local film producers-distributors-exhibitors (including Layar Tancap/traveling cinema companies), and domestic mainstream audience, as well as international distributors.

Research Interests:

Indonesia‟s New Order Government (1966-1998) was notorious for its state-control of every aspect of life. In the film industry, the government applied sharp censorship and controlled film production by controlling scripts and film... more

Indonesia‟s New Order Government (1966-1998) was notorious for its state-control of every aspect of life. In the film industry, the government applied sharp censorship and controlled film production by controlling scripts and film bodies as well as distribution and exhibition. This paper explores how the New Order and its policies valued and dealt with the subcultures of Layar Tancap (open air cinema) and bioskop keliling (mobile cinema shows)? According to Katinka van Heeren, Layar Tancap shows were off of the New Order‟s radar until 1993, the year the government finally acknowledged and formalized Perfiki

(Persatuan Perusahaan Pertunjukan Film Keliling Indonesia, or the Union of Indonesian Mobile Cinema Show). Both van Heeren and Krishna Sen, have argued that while its spectatorship is important to note, no specific official policies were applied and no data was collected by The Indonesian Statistical Bureau for this open air cinema. In short, layar

tancap was overlooked by the New Order government because the spectators were from the lower and working classes. Drawing on the evidence of the New Order‟s film policies

as well as general and trade magazines, my research questions van Heeren‟s assertion. I will argue that Suharto‟s government tried to frame this kind of distribution and exhibition cultures long before 1993, precisely because the villagers were one of their important assets; they formed the large majority of Indonesian citizens. I will also discuss how the practice and consumption of layar tancap and the policies of New Order government interact, negotiate, and influence each other.

(Persatuan Perusahaan Pertunjukan Film Keliling Indonesia, or the Union of Indonesian Mobile Cinema Show). Both van Heeren and Krishna Sen, have argued that while its spectatorship is important to note, no specific official policies were applied and no data was collected by The Indonesian Statistical Bureau for this open air cinema. In short, layar

tancap was overlooked by the New Order government because the spectators were from the lower and working classes. Drawing on the evidence of the New Order‟s film policies

as well as general and trade magazines, my research questions van Heeren‟s assertion. I will argue that Suharto‟s government tried to frame this kind of distribution and exhibition cultures long before 1993, precisely because the villagers were one of their important assets; they formed the large majority of Indonesian citizens. I will also discuss how the practice and consumption of layar tancap and the policies of New Order government interact, negotiate, and influence each other.

Research Interests:

After passing through the strict censorship board and 9 days of theatrical release, Pembalasan Ratu Laut Selatan (Tjut Djalil, 1988) or Lady Terminator was withdrawn from national distribution due to concerns over its sexual and violence... more

After passing through the strict censorship board and 9 days of theatrical release, Pembalasan Ratu Laut Selatan (Tjut Djalil, 1988) or Lady Terminator was withdrawn from national distribution due to concerns over its sexual and violence scenes. Society blamed censorship board for being too soft, and there were suggestions of bribery. Threats were made to sue the board.

The situation above is unique given the New Order regime’s (1966-1998) notorious state control of every aspect of life, including sharp censorship and control of film organizations. The government also framed movies to “represent the true Indonesian cultures”, which meant excluding violence and erotic scenes from the screen. On the other hand, it was the public who took action in opposing the film.

The film caused moral panics within the society because it was considered a ‘threat to societal values and interests’ (Cohen, 1972, p.9) and challenged legitimate culture. By looking at the media reception in 1988, this paper will investigate the bigger context of Indonesia’s political and social situation regarding the withdrawal of the film and social anxiety surrounding it. In particular, I want to interrogate how various Politics of Tastes (government, culture elites, society, and film producers) were contradicted and negotiated through this case.

The situation above is unique given the New Order regime’s (1966-1998) notorious state control of every aspect of life, including sharp censorship and control of film organizations. The government also framed movies to “represent the true Indonesian cultures”, which meant excluding violence and erotic scenes from the screen. On the other hand, it was the public who took action in opposing the film.

The film caused moral panics within the society because it was considered a ‘threat to societal values and interests’ (Cohen, 1972, p.9) and challenged legitimate culture. By looking at the media reception in 1988, this paper will investigate the bigger context of Indonesia’s political and social situation regarding the withdrawal of the film and social anxiety surrounding it. In particular, I want to interrogate how various Politics of Tastes (government, culture elites, society, and film producers) were contradicted and negotiated through this case.

Research Interests:

For Indonesians, particularly for Generation of the 1980s, it is commonly known that Si Unyil , Indonesian TV puppet show series, is the most popular TV program in the 1980s (Kitley 153). Since 1 April 1981, every Sunday morning,... more

For Indonesians, particularly for Generation of the 1980s, it is commonly known that Si Unyil , Indonesian TV puppet show series, is the most popular TV program in the 1980s (Kitley 153). Since 1 April 1981, every Sunday morning, from 1981 to 1993, most of the children in Indonesia sit in their own houses, or in neighbors’ houses and district offices, to watch the show on TV, and later memorize the songs, imitate the dialogs, and discuss the stories. It became a weekly ritual for kids (Imanda 2004, 51).

The paper will interrogate why and how it has deep influence in pop culture. If the reason is its cult status that made the phenomenon, to what extent can we consider Si Unyil as a cult TV program, considering Indonesia in the 1980s and 2010s have different kind of dynamics and characteristics that may be different from Western cult media and may not be always compatible with mainstream Western cult theories ?

I will investigate the connection between the TV program with its cult status in relation with childhood nostalgia, collective memory shared within The 1980s generation, and fans productivities

The paper will interrogate why and how it has deep influence in pop culture. If the reason is its cult status that made the phenomenon, to what extent can we consider Si Unyil as a cult TV program, considering Indonesia in the 1980s and 2010s have different kind of dynamics and characteristics that may be different from Western cult media and may not be always compatible with mainstream Western cult theories ?

I will investigate the connection between the TV program with its cult status in relation with childhood nostalgia, collective memory shared within The 1980s generation, and fans productivities

Research Interests:

Indonesia’s New Order Government (1966-1998) is notorious with its state-control of every aspect of life. In the film industry, the government applied sharp censorship and controlled film production by controlling the script and film... more

Indonesia’s New Order Government (1966-1998) is notorious with its state-control of every aspect of life. In the film industry, the government applied sharp censorship and controlled film production by controlling the script and film bodies as well as distribution and exhibition. (Sen 1992; Heider 1991, Jufry 1992, Said 1991).

How did New Order and its policies value and deal with the subculture of Layar Tancap (open air cinema) or bioskop keliling (mobile cinema shows)? According to Katinka van Heeren, Layar Tancap shows were out of New Order’s radar until 1993 (van Heeren 2012, 33), the year the government finally acknowledged and formalized Perfiki (Persatuan Perusahaan Pertunjukan Film Keliling Indonesia, or the Union of Indonesian Mobile Cinema Show)

According to van Heeren and Krishna Sen, although its spectatorship is important to note, but no specific official policies was applied ; and no data was collected by The Indonesian Statistical Bureau, for this open air cinema (Sen 1994). The Indonesian Statistical Bureau (PBS, Pusat Biro Statistik) only covered numbers from ordinary cinemas in the big cities (Sen 1994, 72).